Intellectual Property Rights, Innovation in Developing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEPICTIONS of CHASTITY: VIRTUE MADE VISIBLE Susan L'engle In

DEPICTIONS OF CHASTITY: VIRTUE MADE VISIBLE Susan L’Engle In 1969 a daughter was born to Cher and Sonny Bono. They named her Chastity, an uncommon and burdensome name for a child to bear in this time and place. The negative resonance of this name still prevails, clearly articulated in a 1996 interview with Chastity Bono, where the reporter commented: “When she was born in 1969, Chastity Bono got stuck with that name forever. ‘Not that many people call me Chastity anyway,’ she says. She prefers Chas. Hell, wouldn’t you?”1 Today in the twenty-fi rst century we all have personal takes on the meaning of the word chastity and its relevance to our individual lives, shaped by our upbringing and education and supplemented by input from various media. In the Middle Ages, however, chastity was an all- pervading and multivalent concept that regulated the lives of lay men and women, and clergy alike. The ideals of chastity were expressed verbally by churchmen, theologians, philosophers, poets, and heads of family—and recorded in sermons, Saints’ Lives, advice manuals for rulers, courtesy books, and poems of courtly romance. For many of these texts, artists created images and compositions to illustrate and reinforce the verbal discourse, and it is these visual manifestations that will be analyzed and discussed in this project. As a medievalist I am interested in the various ramifi cations of chas- tity within the strata of medieval society; as an art historian, I want to explore how the notion of chastity can be represented visually, and what circumstances provoke its illustration. -

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

How Marvel and Sony Sparked Public

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 69 Issue 4 Article 8 6-18-2021 America's Broken Copyright Law: How Marvel and Sony Sparked Public Debate Surrounding the United States' "Broken" Copyright Law and How Congress Can Prevent a Copyright Small Claims Court from Making it Worse Izaak Horstemeier-Zrnich Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Izaak Horstemeier-Zrnich, America's Broken Copyright Law: How Marvel and Sony Sparked Public Debate Surrounding the United States' "Broken" Copyright Law and How Congress Can Prevent a Copyright Small Claims Court from Making it Worse, 69 Clev. St. L. Rev. 927 (2021) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev/vol69/iss4/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICA’S BROKEN COPYRIGHT LAW: HOW MARVEL AND SONY SPARKED PUBLIC DEBATE SURROUNDING THE UNITED STATES’ “BROKEN” COPYRIGHT LAW AND HOW CONGRESS CAN PREVENT A COPYRIGHT SMALL CLAIMS COURT FROM MAKING IT WORSE IZAAK HORSTEMEIER-ZRNICH* ABSTRACT Following failed discussions between Marvel and Sony regarding the use of Spider-Man in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, comic fans were left curious as to how Spider-Man could remain outside of the public domain after decades of the character’s existence. -

Salton Sea Current and Projected Elevations DRAFT Apr 16, 2015

Salton Sea Current and Projected Elevations DRAFT Apr 16, 2015 Mecca W h i te w a te r R iv e r «¬111 North Shore Riverside County Salton Chocolate Sea k ree lt C State Sa Recreation Mountain Area Aerial Desert Salton Gunnery Shores Sea Bombay Range Beach State Salton Sea Beach Recreation Area California Fish Anza and Wildlife Borrego Imperial Wildlife Desert Area State Wister Unit Park Salton City San Niland Diego County VU86 Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge A l a m o R i v e r VU78 k ree e C elip iver F New R San «¬78 Imperial County 86 «¬ Westmorland 0 1.25 2.5 5 7.5 10 Miles Bathymetry data obtained from the State of California and the United States Geological Land Ownership Legend Survey. Estimated Salton Sea elevations identified on this Contour -235 ft msl (Approx. elevation in the 1950's) Other Owners map are from the IID's Salton Sea hydrologic model (SALSA2). The data shown may not agree with Contour -242 ft msl (Estimated elevation 2025) Torres Martinez Tribe those projected by similar models developed previously due to differences in parameters Bureau of Reclamation incorporated into model development. Rate of Contour -248 ft msl (Estimated elevation in 2035) Not Reclamatoin Managed (Withdrawn Not Managed by Reclamation) recession may vary from this estimate and is Bureau of Reclamation dependent on future use and environmental Contour -249 ft msl (Estimated elevation in 2065) Reclamation Withdrawn, Reclamation (Withdrawn and Managed by Reclamation) conditions. Source of 1950 Elevation: Cohen, M. -

Congressional Record—House H5540

H5540 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE July 15, 1998 Neumann Roemer Stenholm Deal Kingston Redmond Kilpatrick Miller (CA) Shays Ney Rogan Strickland DeLay Kleczka Regula Kind (WI) Mink Sherman Northup Rogers Stump Diaz-Balart Klink Reyes Klug Moran (VA) Sisisky Norwood Rohrabacher Stupak Dickey Knollenberg Riggs Lampson Morella Skaggs Nussle Ros-Lehtinen Sununu Doolittle Kolbe Riley Lantos Nadler Slaughter Oberstar Roukema Talent Doyle Kucinich Roemer Lee Olver Smith, Adam Obey Royce Tanner Dreier LaFalce Rogan Levin Owens Stabenow Ortiz Ryun Tauzin Duncan LaHood Rogers Lewis (GA) Pallone Stark Oxley Salmon Taylor (MS) Dunn Largent Rohrabacher Lofgren Pastor Stokes Packard Sanford Taylor (NC) Ehlers Latham Ros-Lehtinen Lowey Paul Tauscher Pappas Saxton Thomas Ehrlich LaTourette Roukema Luther Payne Thompson Parker Scarborough Thornberry Emerson Lazio Royce Maloney (CT) Pelosi Thurman Pascrell Schaefer, Dan Thune English Leach Ryun Maloney (NY) Pickett Tierney Paul Schaffer, Bob Tiahrt Ensign Lewis (CA) Salmon Markey Price (NC) Torres Paxon Sensenbrenner Traficant Etheridge Lewis (KY) Sandlin Martinez Rangel Towns Pease Sessions Turner Everett Linder Sanford Matsui Rivers Velazquez Peterson (MN) Shadegg Upton Ewing Lipinski Saxton McCarthy (MO) Rodriguez Visclosky Peterson (PA) Shaw Walsh Fawell Livingston Scarborough McDermott Rothman Waters Petri Shimkus Wamp Foley LoBiondo Schaefer, Dan McGovern Rush Watt (NC) Pickering Shuster Watkins Forbes Lucas Schaffer, Bob McKinney Sabo Waxman Pitts Skeen Watts (OK) Fossella Manton Sensenbrenner Meehan -

Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge

63502 Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 199 / Friday, October 15, 2010 / Notices court order in National Coalition for the Fax: Attn: Victoria Touchstone, (760) Each unit of the National Wildlife Homeless v. Veterans Administration, 930–0256. Refuge System was established for No. 88–2503–OG (D.D.C.), HUD U.S. Mail: Victoria Touchstone, U.S. specific purposes. We use these publishes a Notice, on a weekly basis, Fish and Wildlife Service, Refuge purposes as the foundation for identifying unutilized, underutilized, Planning, 6010 Hidden Valley Road, developing and prioritizing the excess and surplus Federal buildings Suite 101, Carlsbad, CA 92011. management goals and objectives for and real property that HUD has In-Person Drop-off: You may drop off each refuge within the National Wildlife reviewed for suitability for use to assist comments at the Sonny Bono Salton Sea Refuge System mission, and to the homeless. Today’s Notice is for the NWR Office between 8 a.m. to 3 p.m.; determine how the public can use each purpose of announcing that no please call (760) 348–5278 for refuge. The planning process is a way additional properties have been directions. for us and the public to evaluate determined suitable or unsuitable this management goals, objectives, and FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: week. strategies that will ensure the best Victoria Touchstone, Refuge Planner, at possible approach to wildlife, plant, and Dated: October 7, 2010. 760–431–9440, extension 349, or Chris habitat conservation, while providing Mark R. Johnston, Schoneman, Project Leader, at 760–348– for wildlife-dependent recreation Deputy Assistant Secretary for Special Needs. -

H 3855 but I Would Say Here It Is a New Day, Vermont: Patrick J

March 28, 1995 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE H 3855 But I would say here it is a new day, Vermont: Patrick J. Leahy (D). Washington: Richard ``Doc'' Hastings (R). a new Congress. The GOP is in control, Washington: Patty Murray (D). Wisconsin: Thomas M. Barrett, (D); Gerald at least for another year and 7 months. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES D. Kleczka (D); Scott L. Klug (R); David R. Come home. Vote with Mother Teresa. Alabama: Sonny Callahan (R). Obey (D); Toby Roth (R). Recognize abortion for the intrinsic Arizona: Ed Pastor (D). RELIGION ON THE HILL California: Bill Baker (R); Xavier Becerra evil and the unspeakable crime that it Affiliations for members of the 104th Con- (D); Brian P. Bilbray (R); Sonny Bono (R); gress: 344 Protestant, 149 Catholic, 34 Jewish, is. And you are going to feel good be- Christopher Cox (R); Robert K. Dornan (R); 6 Orthodox, and 7 Other. cause careerism has made cowards out Anna G. Eshoo (D); Matthew G. Martinez (D); Source: Congressoinal Quarterly. of at least a third of Catholics in this George Miller (D); Nancy Pelosi (D); Richard House and out of the majority of W. Pombo (R); George P. Radanovich (R); f Catholics in the other body. Lucille Roybal-Allard (D); Ed Royce (R); An- The figures are there. We are at an drea Seastrand (R). The SPEAKER pro tempore. Under a all-time high: 128 in the House, 21 in Colorado: Scott McInnis (R); Dan Schaefer previous order of the House, the gen- the Senate; 74 Democrats, 54 Repub- (R). tleman from Oregon [Mr. -

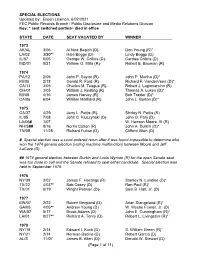

Special Election Dates

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

OXNARD: the MELLOW MALIBU In-The-Know Players Are Heading an Hour up the Coast to Ventura County’S Quieter Beach Scene, the Montauk of Socal by Gary Baum

This $5.5 million property, with sand on its west and south sides, is at 1251 Capri Way in Mandalay Shores. RE/MAX’s Cuoco has the listing. OXNARD: THE MELLOW MALIBU In-the-know players are heading an hour up the coast to Ventura County’s quieter beach scene, the Montauk of SoCal By Gary Baum S THE SECOND-HOME SUMMER agent Susan Blau puts it: “If this were back east, season hits high gear and Malibu Oxnard would be Montauk and Malibu would be begins to yet again resemble East Hampton.” a zoo, savvy industry players The neighboring stretches of the Oxnard 901 Mandalay Beach Road features four eager to skip the scene but coast — from north to south are Mandalay bedrooms and a pedigreed past: Sonny Bono and keep the sunscreen are Shores, Hollywood Beach and Silver Strand Cher (inset) once lived there. It’s on the market for $2.2 million; Cuoco has this listing as well. Aheading a bit farther up the coast to the — long have been a favorite of those in beaches of Oxnard in Ventura County, the business: from The Sheik, starring $3 million versus $8 million to $10 million in on the way to Santa Barbara. Fox Filmed Rudolph Valentino, being shot on its dunes Malibu. Plus, you are not going to run into your Entertainment co-chief Jim Gianopulos Gianopulos to Clark Gable and Carole Lombard famously boss, or someone who is going to pitch something has a place there, along with the likes of sharing a quaint wooden bungalow in the to you. -

MICROCOMP Output File

FINAL EDITION OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS . OCTOBER 4, 1996 Compiled by ROBIN H. CARLE, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Republicans in roman (236); Democrats in italic (196); Independent in SMALL CAPS (1); vacancies (2) 2d AR, 2d TX; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member’s district. ALABAMA 1 Sonny Callahan ........................................... Mobile 2 Terry Everett ............................................... Enterprise 3 Glen Browder .............................................. Jacksonville 4 Tom Bevill ................................................... Jasper 5 Robert E. (Bud) Cramer, Jr. ........................ Huntsville 6 Spencer Bachus ........................................... Vestavia Hills 7 Earl F. Hilliard ........................................... Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young ................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Matt Salmon ................................................ Mesa 2 Ed Pastor ..................................................... Phoenix 3 Bob Stump ................................................... Tolleson 4 John B. Shadegg .......................................... Phoenix 5 Jim Kolbe ..................................................... Tucson 6 J. D. Hayworth ............................................ Scottsdale ARKANSAS 1 Blanche Lambert Lincoln ........................... Helena 2 ——— ——— 1 -

Media and Gender: How Has the Story of Chaz Bono Impacted Mediaâ•Žs

Running Head: TRANSGENDER MEDIA PORTRAYAL 1 Media and gender: How has the story of Chaz Bono impacted media’s portrayal of transgender people? Scott A. Eldredge Iveta Imre University of Tennessee College of Communication & Information TRANSGENDER MEDIA PORTRAYAL 2 Abstract The coverage of transgender issues in serious media is relatively new and has been on the rise. In fact, the amount of stories covering this issue on the major networks and cable news programs in the United States nearly doubled in 2007 compared to 2006 (Hollar, 2007). Despite the fact that this topic is becoming less taboo, and is more frequently treated as socially and politically important, the coverage has still been predominately sensationalistic. For example, the controversy surrounding the pregnancy of a transgender male, Thomas Beatie, in 2008 was headline news for months, while the first-ever congressional hearing on transgender issues and the beating of a transgender woman in Memphis were barely mentioned (Kalter, 2008). In addition, research has shown that the coverage of transgender issues has been at times highly offensive. The mainstream media tends to publish stories that feature transgender people involved in crime or scandal. Some news outlets, such as The New York Post and New York Daily News often feature headlines that refer to transgender people with sensational and dehumanizing terms such as “trannies,” “he-turned-she,” or “transvestite hooker” (Hollar, 2007). Furthermore, the coverage of transgender issues tends to focus on anatomy. The media most often want to describe, define, and explain transgender people, instead of talking about the systematic discrimination they face on a daily basis or their political struggles and victories. -

Women in Congress, 1917-2020: Service Dates and Committee Assignments by Member, and Lists by State and Congress

Women in Congress, 1917-2020: Service Dates and Committee Assignments by Member, and Lists by State and Congress Updated December 4, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL30261 Women in Congress, 1917-2020 Summary In total 366 women have been elected or appointed to Congress, 247 Democrats and 119 Republicans. These figures include six nonvoting Delegates, one each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and American Samoa, and two from the U.S. Virgin Islands, as well as one Resident Commissioner from Puerto Rico. Of these 366 women, there have been 309 (211 Democrats, 98 Republicans) women elected only to the House of Representatives; 41 (25 Democrats, 16 Republicans) women elected or appointed only to the Senate; and 16 (11 Democrats, 5 Republicans) women who have served in both houses. A record 131 women were initially sworn in for the 116th Congress. One female House Member has since resigned, one female Senator was sworn in January 2020, and another female Senator was appointed in 2019 to a temporary term that ended in December 2020. Of 130 women currently in Congress, there are 25 in the Senate (17 Democrats and 8 Republicans); 101 Representatives in the House (88 Democrats and 13 Republicans); and 4 women in the House (2 Democrats and 2 Republicans) who serve as Delegates or Resident Commissioner, representing the District of Columbia, American Samoa, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico. This report includes brief biographical information, committee assignments, dates of service, district information, and listings by Congress and state, and (for Representatives) congressional districts of the 366 women who have been elected or appointed to Congress.