©2014 Catherine Aust ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

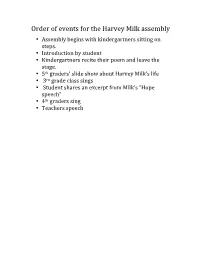

Order of Events for the Harvey Milk Assembly • Assembly Begins with Kindergartners Sitting on Steps

Order of events for the Harvey Milk assembly • Assembly begins with kindergartners sitting on steps. • Introduction by student • Kindergartners recite their poem and leave the stage. • 5th graders’ slide show about Harvey Milk’s life • 3rd grade class sings • Student shares an excerpt from Milk’s “Hope speech” • 4th graders sing • Teachers speech Student 1 Introduction Welcome students of (School Name). Today we will tell you about Harvey Milk, the first gay City Hall supervisor. He has changed many people’s lives that are gay or lesbian. People respect him because he stood up for gay and lesbian people. He is remembered for changing our country, and he is a hero to gay and lesbian people. Fifth Grade Class Slide Show When Harvey Milk was a little boy he loved to be the center of attention. Growing up, Harvey was a pretty normal boy, doing things that all boys do. Harvey was very popular in school and had many friends. However, he hid from everyone a very troubling secret. Harvey Milk was homosexual. Being gay wasn’t very easy back in those days. For an example, Harvey Milk and Joe Campbell had to keep a secret of their gay relationship for six years. Sadly, they broke up because of stress. But Harvey Milk was still looking for a spouse. Eventually, Harvey Milk met Scott Smith and fell in love. Harvey and Scott moved together to the Castro neighborhood of San Francisco, which was a haven for people who were gay, a place where they were respected more easily. Harvey and Scott opened a store called Castro Camera and lived on the top floor. -

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. THEMES The chapters in this section take themes as their starting points. They explore different aspects of LGBTQ history and heritage, tying them to specific places across the country. They include examinations of LGBTQ community, civil rights, the law, health, art and artists, commerce, the military, sports and leisure, and sex, love, and relationships. MAKING COMMUNITY: THE PLACES AND15 SPACES OF LGBTQ COLLECTIVE IDENTITY FORMATION Christina B. Hanhardt Introduction In the summer of 2012, posters reading "MORE GRINDR=FEWER GAY BARS” appeared taped to signposts in numerous gay neighborhoods in North America—from Greenwich Village in New York City to Davie Village in Vancouver, Canada.1 The signs expressed a brewing fear: that the popularity of online lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) social media—like Grindr, which connects gay men based on proximate location—would soon replace the bricks-and-mortar institutions that had long facilitated LGBTQ community building. -

Thematic Review: American Gay Rights Movement Directions and Obje

Name:_____________________________________ Class Period:______ Thematic Review: American Gay Rights Movement Although the topic of homosexuality continues to ignite passionate debate and is often omitted from history discussions due to the sensitivity of the topic, it is important to consider gays and lesbians when defining and analyzing modern American identity. The purpose of this activity is to review the struggle for respect, dignity, and equal protection under the law that so many have fought for throughout American history. Racial minorities… from slaves fighting for freedom to immigrants battling for opportunity… to modern-day racial and ethnic minorities working to overcome previous and current inequities in the American system. Women… fighting for property rights, education, suffrage, divorce, and birth control. Non- Protestants… from Catholics, Mormons, and Jews battling discrimination to modern day Muslims and others seeking peaceful co-existence in this “land of the free.” Where do gays and lesbians fit in? Once marginalized as criminals and/or mentally ill, they are increasingly being included in the “fabric” we call America. From the Period 8 Content Outline: Stirred by a growing awareness of inequalities in American society and by the African American civil rights movement, activists also addressed issues of identity and social justice, such as gender/sexuality and ethnicity. Activists began to question society’s assumptions about gender and to call for social and economic equality for women and for gays and lesbians. Directions and Objectives: Review the events in the Gay Rights Thematic Review Timeline, analyze changes in American identity, and make connections to other historically significant events occurring along the way. -

L E S B I a N / G

LESBIAN/GAY L AW JanuaryN 2012 O T E S 03 11th Circuit 10 Maine Supreme 17 New Jersey Transgender Ruling Judicial Court Superior Court Equal Protection Workplace Gestational Discrimination Surrogacy 05 Obama Administration 11 Florida Court 20 California Court Global LGBT Rights of Appeals of Appeal Parental Rights Non-Adoptive 06 11th Circuit First Same-Sex Co-Parents Amendment Ruling 14 California Anti-Gay Appellate Court 21 Texas U.S. Distict Counseling Non-Consensual Court Ruling Oral Copulation High School 09 6th Circuit “Outing” Case Lawrence- 16 Connecticut Based Challenge Appellate Ruling Incest Conviction Loss of Consortium © Lesbian/Gay Law Notes & the Lesbian/Gay Law Notes Podcast are Publications of the LeGaL Foundation. LESBIAN/GAY DEPARTMENTS 22 Federal Civil Litigation Notes L AW N O T E S 25 Federal Criminal Litigation Editor-in-Chief Notes Prof. Arthur S. Leonard New York Law School 25 State Criminal Litigation 185 W. Broadway Notes New York, NY 10013 (212) 431-2156 | [email protected] 26 State Civil Litigation Notes Contributors 28 Legislative Notes Bryan Johnson, Esq. Brad Snyder, Esq. 30 Law & Society Notes Stephen E. Woods, Esq. Eric Wursthorn, Esq. 33 International Notes New York, NY 36 HIV/AIDS Legal & Policy Kelly Garner Notes NYLS ‘12 37 Publications Noted Art Director Bacilio Mendez II, MLIS Law Notes welcomes contributions. To ex- NYLS ‘14 plore the possibility of being a contributor please contact [email protected]. Circulation Rate Inquiries LeGaL Foundation 799 Broadway Suite 340 New York, NY 10003 THIS MONTHLY PUBLICATION IS EDITED AND (212) 353-9118 | [email protected] CHIEFLY WRIttEN BY PROFESSOR ARTHUR LEONARD OF NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL, Law Notes Archive WITH A STAFF OF VOLUNTEER WRITERS http://www.nyls.edu/jac CONSISTING OF LAWYERS, LAW SCHOOL GRADUATES, AND CURRENT LAW STUDENTS. -

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

Reach More of the Gay Market

Reach More of the Gay Market Mark Elderkin [email protected] (954) 485-9910 Evolution of the Gay Online Ad Market Concentration A couple of sites with reach Fragmentation Many sites with limited reach Gay Ad Network Aggregation 3,702,065 Monthly Gay Ad Network creates reach Unique Users (30-day Reach by Adify - 04/08) 1995 2000 2005 2010 2 About Gay Ad Network Gay Ad Network . The Largest Gay Audience Worldwide comScore Media Metrix shows that Gay Ad Network has amassed the largest gay reach in the USA and Health & Fitness abroad. (July 2008) Travel & Local . Extensive Network of over 200 LGBT Sites Entertainment Our publisher’s content is relevant and unique. We News & Politics do not allow chat rooms or adult content on our network. All publishers adhere to our strict editorial Women guidelines. Pop Culture . 100% Transparency for Impressions Delivered Parenting Performance reports show advertisers exactly where and when ads are delivered. Ad impressions are Business & Finance organic and never forced. Style . Refined Targeting or Run of Network Young Adult For media efficiency, campaigns can be site targeted, frequency-capped, and geo-targeted. For mass reach, we offer a run of network option. 3 Gay Ad Network: The #1 Gay Media Network Unique US Audience Reach comScore Media Metrix July 2008 . Ranked #1 by 750,000 comScore Media Metrix in Gay and Lesbian Category 500,000 . The fastest growing gay media property. 250,000 . The greatest 0 diversity and Gay Ad PlanetOut LOGOonline depth of content Network Network Network and audience The comScore July 2008 traffic report does not include site traffic segments. -

Sip-In" That Drew from the Civil Rights Movement by History.Com, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 11.07.19 Word Count 887 Level 1020L

The gay "sip-in" that drew from the civil rights movement By History.com, adapted by Newsela staff on 11.07.19 Word Count 887 Level 1020L Image 1. A bartender in Julius's Bar refuses to serve John Timmins, Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell and Randy Wicker, members of the Mattachine Society, an early American gay rights group, who were protesting New York liquor laws that prevented serving gay customers on April 21, 1966. Photo from: Getty Images/Fred W. McDarrah. In 1966, on a spring afternoon in Greenwich Village, three men set out to change the political and social climate of New York City. After having gone from one bar to the next, the men reached a cozy tavern named Julius'. They approached the bartender, proclaimed they were gay and then requested a drink, but were promptly denied service. The trio had accomplished their goal: their "sip-in" had begun. The men belonged to the Mattachine Society, an early organization dedicated to fighting for gay rights. They wanted to show that bars in the city discriminated against gay people. Discrimination against the gay community was a common practice at the time. Still, this discrimination was less obvious than the discriminatory Jim Crow laws in the South that forced racial segregation. Bartenders Refused Service To Gay Couples This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. A person's sexual orientation couldn't be detected as easily as a person's sex or race. With that in mind, the New York State Liquor Authority, a state agency that controls liquor sales, took action. -

Youth Theater

15_144398 bindex.qxp 7/25/07 7:39 PM Page 390 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX African Paradise, 314 Anthropologie, 325 A Hospitality Company, 112 Antiques and collectibles, AIDSinfo, 29 318–319 AARP, 52 AirAmbulanceCard.com, 51 Triple Pier Antiques Show, ABC Carpet & Home, 309–310, Airfares, 38–39 31, 36 313–314 Airlines, 37–38 Apartment rentals, 112–113 Above and Beyond Tours, 52 Airports, 37 Apollo Theater, 355–356 Abyssinian Baptist Church, getting into town from, 39 Apple Core Hotels, 111 265–266 security measures, 41 The Apple Store, 330 Academy Records & CDs, 338 Air-Ride, 39 Architecture, 15–26 Access-Able Travel Source, 51 Air Tickets Direct, 38 Art Deco, 24–25 Access America, 48 Air tours, 280 Art Moderne, 25 Accessible Journeys, 51 AirTrain, 42–43 Beaux Arts, 23 Accommodations, 109–154. AirTran, 37 best structures, 7 See also Accommodations Alexander and Bonin, 255 early skyscraper, 21–22 Index Alice in Wonderland (Central Federal, 16, 18 bedbugs, 116 Park), 270 Georgian, 15–16 best, 9–11 Allan & Suzi, 327 Gothic Revival, 19–20 chains, 111 Allen Room, 358 Greek Revival, 18 Chelsea, 122–123 All State Cafe, 384 highlights, 260–265 family-friendly, 139 Allstate limousines, 41 International Style, 23–24 Greenwich Village and the Alphabet City, 82 Italianate, 20–21 Meat-Packing District, Alphaville, 318 late 19th century, 20 119–122 Amato Opera Theatre, 352 Postmodern, 26 Midtown East and Murray American Airlines, 37 Second Renaissance Revival, Hill, 140–148 American Airlines Vacations, 57 -

For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2014 For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism Kelly Anderson Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/8 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] For Love and For Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism By Kelly Anderson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The Graduate Center, City University of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History 2014 © 2014 KELLY ANDERSON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Blanche Wiesen Cook Chair of Examining Committee Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Bonnie Anderson Bettina Aptheker Gerald Markowitz Barbara Welter Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism By Kelly Anderson Adviser: Professor Blanche Wiesen Cook This dissertation explores the role of lesbians in the U.S. second wave feminist movement, arguing that the history of women’s liberation is more diverse, more intersectional, -

Big Assembly Win Sends Marriage Bill to Senate

AMERICA’S LARGEST CIRCULATION GAY AND LESBIAN NEWSPAPER! NEWSTM YOUR FREE LGBT NEWSPAPER MAY 14-27, 2009 VOL. EIGHT, ISS. 10 SERVINGGay GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANSGENDERED City NEW YORK • WWW.GAYCITYNEWS.COM ■ CRIME ■ BOOKS DA Probe Tackling Appears Stalled Southern BY DUNCAN OSBORNE Gothic’s Queen hile activists and elected offi- BY MICHAEL EHRHARDT cials believed that District W Attorney Robert Morgenthau rad Gooch has fulfilled a long promised at a March 6 meeting to inves- harbored wish to write the defin- tigate the arrests of gay and bisexual B itive biography of the queen of men in Manhattan porn shops, com- grotesque “grit-lit,” Flannery O’Connor, ments made by an assistant district and it was well worth the two decades’ attorney during a trial suggest that any wait. Gooch, who confesses a “literary such investigation has produced little fascination” with his subject, has hand- information. ily tackled the life of this recondite and “Have there been any conclusions canonic American writer who died from reached in this investigation?” said Rich- lupus at age 39. Long before John Ber- ard M. Weinberg, the judge who presides endt’s “Midnight in the Garden of Good in Midtown Community Court, at the and Evil” chronicled the eccentric char- start of a May 5 prostitution trial. Andres acters and macabre manners of the Torres, the assistant district attorney inhabitants of Savannah, Georgia, the who was handling the case, said “No, GOOCH P. 28 your honor.” The questioning came as Linda GAY CITY NEWS CITY GAY DA PROBE P. 8 SENATOR TOM DUANE’S -

Dp Harvey Milk

1 Focus Features présente en association avec Axon Films Une production Groundswell/Jinks/Cohen Company un film de GUS VAN SANT SEAN PENN HARVEY MILK EMILE HIRSCH JOSH BROLIN DIEGO LUNA et JAMES FRANCO Durée : 2h07 SORTIE NATIONALE LE 4 MARS 2008 Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.snd-films.com DISTRIBUTION : RELATIONS PRESSE : SND JEAN-PIERRE VINCENT 89, avenue Charles-de-Gaulle SOPHIE SALEYRON 92575 Neuilly-sur-Seine Cedex 12, rue Paul Baudry Tél. : 01 41 92 79 39/41/42 75008 Paris Fax : 01 41 92 79 07 Tél. : 01 42 25 23 80 3 SYNOPSIS Le film retrace les huit dernières années de la vie d’Harvey Milk (SEAN PENN). Dans les années 1970 il fut le premier homme politique américain ouvertement gay à être élu à des fonctions officielles, à San Francisco en Californie. Son combat pour la tolérance et l’intégration des communautés homosexuelles lui coûta la vie. Son action a changé les mentalités, et son engagement a changé l’histoire. 5 CHRONOLOGIE 1930, 22 mai. Naissance d’Harvey Bernard Milk à Woodmere, dans l’Etat de New York. 1946 Milk entre dans l’équipe de football junior de Bay Shore High School, dans l’Etat de New York. 1947 Milk sort diplômé de Bay Shore High School. 1951 Milk obtient son diplôme de mathématiques de la State University (SUNY) d’Albany et entre dans l’U.S. Navy. 1955 Milk quitte la Navy avec les honneurs et devient professeur dans un lycée. 1963 Milk entame une nouvelle carrière au sein d’une firme d’investissements de Wall Street, Bache & Co. -

Harvey Milk Timeline

Harvey Milk Timeline • 1930: Harvey Bernard Milk is born. • 1947: Milk graduates high school. • 1950: __________________________________________ • 1951: Milk enlists in the Navy. • 1955: Milk is discharged from the Navy. • 1959: __________________________________________ • 1963: __________________________________________ • 1965: __________________________________________ • 1969: __________________________________________ • 1971: __________________________________________ • 1972: __________________________________________ • 1972: Milk moves from New York City to San Francisco. • 1973: Milk opens Castro Camera • 1973: Milk helps the Teamsters with their successful Coors boycott. • 1973: __________________________________________ • 1973: __________________________________________ • 1973: Milk runs for District 5 Supervisor for the first time and loses. • 1975: __________________________________________ • 1976: __________________________________________ • 1976: __________________________________________ • 1977: Milk is elected district Supervisor. • 1977: __________________________________________ • 1977: Milk led Milk led march against the Dade County Ordinance vote. • 1978: The San Francisco Gay Civil Rights Ordinance is signed. • 1978: __________________________________________ • 1978: Milk is assassinated by Dan White. • 1979: __________________________________________ • 1979: People protest Dan White’s sentence. This is known as the White Night. • 1981: __________________________________________ Add the following events into the timeline!