Briefings27 Futureofmedia 22-30

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vice News Lands 19 News & Documentary Emmy

VICE NEWS LANDS 19 NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY NOMINATIONS VICE News Tonight is the most-nominated nightly newscast for two consecutive years Brooklyn, NY (July 25) – Today, it was announced by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences that VICE News has been nominated for 19 News & Documentary Emmy® Awards. In only its third year on air, VICE Media and HBO’s nightly newscast VICE News Tonight earned 18 News & Documentary Emmy® Awards nominations, becoming the most highly nominated nightly show for the second year in a row and more than doubling last year’s total of nine nominations. VICE News Tonight was nominated across 12 categories including: Best Story in a Newscast, Outstanding Coverage of a Breaking News Story in a Newscast, Outstanding Video Journalism and Outstanding News Special. Additionally, the VICE Special Report ‘Panic: The Untold Story of the 2008 Financial Crisis’ was nominated in the Outstanding Business and Economic Documentary, bringing the VICE News total nomination count to 19 total. Madeleine Haeringer, Executive Producer, VICE News Tonight on HBO said: “The nominations, across twelve different categories, truly show the breadth of creativity and coverage of our work. It's a testament to the grit, determination, and unwavering fellowship of the news team that for three years in a row, VICE News Tonight has not only stood shoulder to shoulder with the giants of news, but outright beaten them.” Full list of VICE News nominations: OUTSTANDING COVERAGE OF A BREAKING NEWS STORY IN A NEWSCAST Moment of -

Versailles: French TV Goes Global Brexit: Who Benefits? with K5 You Can

July/August 2016 Versailles: French TV goes global Brexit: Who benefits? With K5 you can The trusted cloud service helping you serve the digital age. 3384-RTS_Television_Advert_v01.indd 3 29/06/2016 13:52:47 Journal of The Royal Television Society July/August 2016 l Volume 53/7 From the CEO It’s not often that I Huw and Graeme for all their dedica- this month. Don’t miss Tara Conlan’s can say this but, com- tion and hard work. piece on the gender pay gap in TV or pared with what’s Our energetic digital editor, Tim Raymond Snoddy’s look at how Brexit happening in politics, Dickens, is off to work in a new sector. is likely to affect the broadcasting and the television sector Good luck and thank you for a mas- production sectors. Somehow, I’ve got looks relatively calm. sive contribution to the RTS. And a feeling that this won’t be the last At the RTS, however, congratulations to Tim’s successor, word on Brexit. there have been a few changes. Pippa Shawley, who started with us Advance bookings for September’s I am very pleased to welcome Lynn two years ago as one of our talented RTS London Conference are ahead of Barlow to the Board of Trustees as the digital interns. our expectations. To secure your place new English regions representative. It may be high summer, but RTS please go to our website. She is taking over from the wonderful Futures held a truly brilliant event in Finally, I’d like to take this opportu- Graeme Thompson. -

OUTDOOR CHANNEL TURNS VICELAND on FRIDAY NIGHTS Viewers in Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines and Vietnam Set to Be the First to Enjoy Exclusive VICELAND Programming

OUTDOOR CHANNEL TURNS VICELAND ON FRIDAY NIGHTS Viewers in Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines and Vietnam set to be the first to enjoy exclusive VICELAND programming SINGAPORE, 25th August 2016 – Outdoor Channel (Asia), The World Leader In Outdoor Entertainment, today announced the exclusive launch of VICELAND Friday Nights on Outdoor Channel, for its viewers in 17 countries and almost 7 million households across Asia. VICELAND, the critically-acclaimed 24-hour lifestyle and cultural TV channel produced by the global youth media company VICE, will launch early 2017 across Southeast Asia in partnership with Multi Channels Asia. As a prelude to that launch, Outdoor Channel viewers will be the first in Asia to get a taste of VICELAND’s distinctive, immersive style of original lifestyle and culture programming. The three-hour VICELAND block will premiere in October on Fridays from 21:00 to Midnight (SG/MY/HKG). Viewers can expect a line-up of VICELAND signature shows including Huang’s World, Woman, Noisey, VICE World of Sports, King of the Road, Black Market, Cyberwar and States of Undress. The VICELAND programming block will give the youth centric audience of Outdoor Channel programming that delves into the curiosities of everything that makes up life today. VICELAND launched in the US and Canada in February 2016, with the channel confirmed to launch in 50 new territories throughout 2016 and 2017, including the UK, France, India, the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa, South East Asia, Australia and New Zealand. ### About VICE Media: VICE is the world’s preeminent youth media company and content creation studio. Launched in 1994, VICE now operates in over 30 countries and distributes its programming to viewers across digital, linear, mobile, film and socials. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

Nat Geo Taps the A-List for Its Latest Premium Play, ‘Breakthrough’ Advances in Biotechnology

NOVEMBER / DECEMBER 15 Nat Geo taps the A-list for its latest premium play, ‘Breakthrough’ CANADA POST AGREEMENT NUMBER 40050265 PRINTED IN CANADA USPS AFSM 100 Approved Polywrap USPS AFSM 100 Approved NUMBER 40050265 PRINTED IN CANADA POST AGREEMENT CANADA US $7.95 USD Canada $8.95 CDN Int’l $9.95 USD G<ID@KEF%+*-* 9L==8CF#EP L%J%GFJK8><G8@; 8LKF ALSO: VR – THE BIG PICTURE | AMY BERG TALKS JANIS GIJIKJK; A PUBLICATIONPUBLICATION OF BRUNICOBRUNICO COMMUNICATIONSCOMMUNICATIONS LTD.LTD. Realscreen Cover.indd 2 2015-11-09 4:33 PM Are you our next winner? Celebrating excellence in non-fi ction and unscripted entertainment Awards will be presented at the 2016 edition of Realscreen West, Santa Monica CA, June 9, 2016 Final entry deadline: Friday, February 5, 2016 To submit your entries go to awards.realscreen.com RS.27203.27200.RSARSW.indd 3 2015-11-10 10:05 AM contents november / december 15 DiscoveryVR intends to teach 13 viewers How to Survive in the Wild 22 through immersive content. BIZ Vice pacts with A+E, Rogers for cable channels; Montgomery set to lead ITV Studios U.S. Group ................................. 9 INGENIOUS Legendary rock icon Janis Joplin is the focal point of Amy Berg’s latest, Janis: Little Girl Blue. Amy Berg celebrates Janis Joplin .......................................................13 SPECIAL REPORTS 26 SCIENCE FOCUS Three science projects that tackle breakthroughs and big questions; a chat with Science Channel’s Marc Etkind ......................16 Couldn’t make it to Realscreen London? See what you VFX/ANIMATION missed in our photo page. Looking at the big picture for virtual reality content; Rebuilding history with CGI ..............................................................22 “It’s so diffi cult now to REALSCREEN LONDON deliver visual spectacle The scene at our UK conference’s second edition .............................26 that makes your eyes AND ONE MORE THING open again.” 18 Chris Evans talks Top Gear ............................................................... -

Vice Tv Announces May Slate

Media Contact Meera Pattni 347-525-3922 [email protected] VICE TV ANNOUNCES MAY SLATE Rappers 2 Chainz and Action Bronson return with new seasons of MOST EXPENSIVEST and F*CK, THAT’S DELICIOUS VICE TV rolls out two new VICE VERSA documentaries examining mainstream media’s coverage of Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign and confronting America’s dark love affair with Nike's iconic Air Jordan sneaker BROOKLYN, NY (MAY 5, 2020) - VICE TV’s new documentary series, VICE VERSA, a series of independent specials that give voice to radical and unapologetic points of view, will premiere two new installments this month; Bernie Blackout, which examines the role corporate media played in the demise of Bernie Sanders’ 2020 Presidential campaign and One Man and His Shoes, a necessary deep dive into the dark side of Nike’s iconic Air Jordan sneakers. In addition, rapper/chef Action Bronson, and his signature series F*ck, That’s Delicious returns for a fourth season while rapper 2 Chainz’s celebration of excess, Most Expensivest, is back for another installment. The announcements come on the heels of VICE TV’s recent launches, Shelter In Place, VICE Media Group founder Shane Smith’s interview series tackling COVID-19 from home; Seat At The Table, a news talk show hosted by noted pundit and former New York Times columnist Anand Giridharadas that takes an unflinching look at how America really works and for whom; and No Mercy No Malice, a new weekly primetime business show hosted by New York Times bestselling author, tech entrepreneur and NYU business professor Scott Galloway premiering May 7 at 10PM ET/PT that pulls back the curtain on the decisions and players driving the economy. -

The Growing Relationship Between Brands and the Entertainment World Is a Big Theme Once Again at Cannes

The growing relationship between brands and the entertainment world is a big theme once again at Cannes. The debate is focused on several growing issues for brands in this space – including the integration of social media and device technology at live events, built through partnerships with the likes of Snapchat and Twitter, and the distribution of branded entertainment through deals with big media companies. Undoubtedly the biggest issue, however, is the need for brands to adapt to a changing world where they are part of a larger entertainment ecosystem. This requires some brave thinking about their brand and its role, together with the ability to connect with and, ultimately, move people in some way. This concern emerged during the Lions Entertainment session ‘What’s Next in the World of Brands and Entertainment?” The point made most forcibly by Jonny Sabbath, of Anheusher- Busch InBev. He stressed the need for those in the brand world to “think like a marketer, act like a producer. As marketers we have to act more like entertainment producers, do less interrupting and more attracting.” Sabbath raised what for me should be a significant focus for brands: bringing something that’s unique, entertaining, or useful to your audience. He cited one of his own projects, the Beerland show on Vice Media’s Viceland that follows craft brewer Meg Gill on a journey to meet home-brewers, to make his point that brands are now engaging with audiences by buying or creating TV shows and then developing their advertising around this entertainment. This requires a different approach for brands, putting themselves more in the role of producer and asking whether people will want to actively engage with the content and whether the product or service has the permission to have a conversation with people at that time, and in that space. -

Vice Bolsters International Leadership Team

VICE BOLSTERS INTERNATIONAL LEADERSHIP TEAM Hosi Simon appointed as Executive Managing Director, International Tamara Howe to lead VICELAND TV EMEA business as Managing Director CJ Fahey will move into a new role as SVP International for VICE Studios TUESDAY 11 JUNE, 2019 - London -- VICE Media today announces a new leadership structure across its international team with new, enhanced roles and promotions for several key executives. Hosi Simon has been appointed as VICE’s Executive Managing Director. Simon will be responsible for overseeing all operational and business activity in APAC, EMEA & LATAM across VICE’s five lines of business – Studios, Television, Digital, News and VIRTUE. Simon has been with the organization for 13 years in multiple roles, most recently as CEO of VICE Asia Pacific where the region has quickly expanded with key partnerships. Under his leadership, VICE APAC recently announced a content partnership with Chinese streaming service Tencent, as well as its first series commission in Japan with Amazon Prime Video. In his new role as Executive Managing Director, Simon will report to Dominique Delport, Chief Revenue Officer & President, International and oversee the continued growth trajectory of the global VICE business where 50% of revenue and audience originates. As the global VICE Studios expands, CJ Fahey will move into a new role as SVP International for VICE Studios, working on the global strategy for the business reporting into Danny Gabai, Head of Vice Studios U.S. Fahey will also be responsible for the management and growth of the international Studios business in EMEA, APAC, and LATAM. Recently, VICE Studios launched a string of recent hits in the UK, including BBC Two’s 'The Brexit Storm: Laura Kuenssberg's Inside Story' and Channel 5's 'The Murder Of Charlene Downes.’ Tamara Howe will now oversee our VICELAND business across EMEA as Managing Director, reporting into Guy Slattery, General Manager VICELAND U.S. -

A+E's Vice Channel Named Viceland, Sets Launch Date for Early 2016

A+E's Vice Channel Named Viceland, Sets Launch Date for Early 2016 11.03.2015 ​The long-rumored 24-hour VICE channel is soon to be a reality. A+E Networks announced Tuesday that H2 will be replaced by Viceland, launching in early 2016. The TV network will be a joint venture with A+E, but will be programmed exclusively by VICE. Viceland, still a working title (and reminiscent of the just-departed Grantland), will take advantage of the multiplatform audience and distribution of the VICE brand in order to launch an on-air network along with digital and social outlets as well. A+E Networks was attracted to the partnership because of VICE's long-standing relationship with younger audiences and multiplatform strategy. "VICE has a bold voice and a distinctive model in the marketplace," said Nancy Dubuc, president and CEO of A+E Networks, in a statement. "This channel represents a strategic fit and a new direction for the future of our portfolio of media assets. Shane Smith has led VICE from a fledgling magazine into a global media brand and all of us at A+E are excited to work with him and his passionate and innovative team." VICE Co-Founder and CEO Shane Smith called the new network "the next step in the evolution of our brand and the first step in our global roll-out of networks around the world." Smith added that the 24-hour channel lets its programming be "platform agnostic," so that its viewers can find VICE content anywhere, anytime, while also ramping up high-quality programming that can "challenge the accepted norms of current TV viewing." "All in all, this new network allows us to continue our innovation in storytelling and content creation and take it to the next level," said Smith in a statement. -

New Consumer Summit Report

New Consumer Summit Report Partner: 02 03 About Summits About Us About EMC CEO : Trevor Hardy An obstacle for many businesses Since it was founded in 2001 The EMC, our partner and Co-founder : Chris Sanderson today is how to build teams Future Laboratory has grown to collaborator on this series of LS:N Global editor-in-chief : Martin Raymond that are armed with fast- become one of the world’s most events, is a renowned cloud, Senior partner : Tom Savigar changing consumer information renowned futures consultancies, data storage and e-solutions Chief strategy and innovation officer : Tracey Follows and capable of applying and has worked with more organisation that sits behind Business development director : Cliff Bunting it strategically. The most than 1,000 brands in 37 many of the brands, products Report editor : Steve Tooze compelling and entertaining countries from offices in London, and services we encounter on a Report leads : Maks Fus Mickiewicz, Rachael Stott way to bring this intelligence Melbourne and New York. day-to-day basis. As with all of LS:N Global editor : Jonathan Openshaw to life is through one of our our partners, we are working The Future Laboratory offers LS:N Global visual editor : Hannah Robinson highly subscribed live events. with EMC to identify the new, a range of services, from LS:N Global insight editor : Daniela Walker next and innovative ideas that Our Summits, held in foresight to inspiration to LS:N Global senior journalist : Maks Fus Mickiewicz, Peter Maxwell are driving, determining and partnership with EMC, are strategic advice and activation. -

Vice Media Group Promotes Veteran News Executive Subrata De to Global Evp, Head of Programming and Development, Vice News

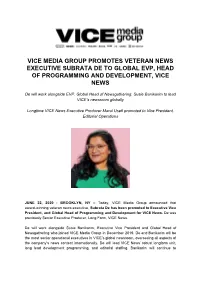

VICE MEDIA GROUP PROMOTES VETERAN NEWS EXECUTIVE SUBRATA DE TO GLOBAL EVP, HEAD OF PROGRAMMING AND DEVELOPMENT, VICE NEWS De will work alongside EVP, Global Head of Newsgathering, Susie Banikarim to lead VICE’s newsroom globally Longtime VICE News Executive Producer Maral Usefi promoted to Vice President, Editorial Operations JUNE 22, 2020 - BROOKLYN, NY – Today, VICE Media Group announced that award-winning veteran news executive, Subrata De has been promoted to Executive Vice President, and Global Head of Programming and Development for VICE News. De was previously Senior Executive Producer, Long Form, VICE News. De will work alongside Susie Banikarim, Executive Vice President and Global Head of Newsgathering who joined VICE Media Group in December 2019. De and Banikarim will be the most senior operational executives in VICE’s global newsroom, overseeing all aspects of the company’s news content internationally. De will lead VICE News’ robust longform unit, long lead development programming, and editorial staffing. Banikarim will continue to marshal all daily newsroom, bureaus and newsgathering functions, including the Emmy®-award winning nightly newscast VICE News Tonight. De started at VICE in May 2018 as Executive Producer of the Emmy®-award winning weekly series VICE on HBO. She was promoted to Senior Executive Producer in 2019, where she led all long-form content including Investigations by VICE on Hulu and VICE on Showtime. During her time at VICE, De has overseen multiple groundbreaking stories including "Consent,” a look at the complexity of confronting sexual assault in the wake of #MeToo; “Losing Ground” an examination into how property laws aid in the appropriation of Black land and; “Warning from Wuhan” a haunting piece reported by a now-disappeared citizen journalist in China. -

Living Large

LIVING LARGE vice’s shane smith Discover more. DRIVE DE CARTIER LARGE DATE, RETROGRADE SECOND TIME ZONE AND DAY/NIGHT INDICATOR 1904-FU MC THE DRIVE DE CARTIER COLLECTION IS ELEGANCE REDEFINED. THE SLEEK LINES OF THIS CUSHION-SHAPED WATCH CREATE A TRULY STYLISH PIECE, BROUGHT TO LIFE BY THE MAISON MANUFACTURE MOVEMENT 1904-FU MC. ITS THREE COMPLICATIONS ARE COORDINATED DIRECTLY BY THE CROWN. ESTABLISHED IN 1847, CARTIER CREATES EXCEPTIONAL WATCHES THAT COMBINE DARING DESIGN AND WATCHMAKING SAVOIR-FAIRE. #WHATDRIVESYOU Shop the new collection on cartier.com HERMÈS BY NATURE A NDREW L AUREN F ILMMAKER RALPHLAUREN.COM/PURPLELABEL ARMANI.COM BOSS 0838/S HUGO BOSS FASHIONS INC. 800 Phone 484 +1 6267 The Art of Tailoring HUGOBOSS.COM Advertisement EVENTS PARSONS 68TH ANNUAL FASHION BENEFIT NEW YORK | 05.23.16 The New School’s Parsons School of Design, in collaboration with its sister school, the College of Performing Arts, hosted its 68th annual fashion benefit, which raised $1.86 million for student scholarships. The benefit introduced the next generation of fashion designers and Donna Karan, Arianna Huffington Patrick Robinson, Virginia Smith honored Sarah Jessica Parker, Donna Karan, Arianna Huffington, and Beth Andy Cohen, Sarah Jessica Parker Rudin DeWoody for their significant EVENTS contributions to social good. Courtesy Getty Images for the New School Aimee Mullins, Rupert Friend Mazdack Rassi, Zanna Roberts Rassi Wes Gordon, Paul Arnhold Sheila Johnson, June Ambrose ONE YEAR OF MANSION GLOBAL NEW YORK | 06.29.16 Mansion Global celebrated its first anniversary at a rooftop soirée hosted by Will Lewis, Chief Executive Officer of Dow Jones and Publisher of The Wall Street Journal.