Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

10-26-2019 Manon Mat.Indd

JULES MASSENET manon conductor Opera in five acts Maurizio Benini Libretto by Henri Meilhac and Philippe production Laurent Pelly Gille, based on the novel L’Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut set designer Chantal Thomas by Abbé Antoine-François Prévost costume designer Saturday, October 26, 2019 Laurent Pelly 1:00–5:05PM lighting designer Joël Adam Last time this season choreographer Lionel Hoche revival stage director The production of Manon was Christian Räth made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund general manager Peter Gelb Manon is a co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; jeanette lerman-neubauer Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Teatro music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin alla Scala, Milan; and Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse 2019–20 SEASON The 279th Metropolitan Opera performance of JULES MASSENET’S manon conductor Maurizio Benini in order of vocal appearance guillot de morfontaine manon lescaut Carlo Bosi Lisette Oropesa* de brétigny chevalier des grieux Brett Polegato Michael Fabiano pousset te a maid Jacqueline Echols Edyta Kulczak javot te comte des grieux Laura Krumm Kwangchul Youn roset te Maya Lahyani an innkeeper Paul Corona lescaut Artur Ruciński guards Mario Bahg** Jeongcheol Cha Saturday, October 26, 2019, 1:00–5:05PM This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from its founding sponsor, The Neubauer Family Foundation. Digital support of The Met: Live in HD is provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies. The Met: Live in HD series is supported by Rolex. -

Musical Times Publications Ltd

Musical Times Publications Ltd. Review Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 27, No. 517 (Mar. 1, 1886), p. 166 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3365196 Accessed: 18-10-2015 06:03 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 134.121.47.100 on Sun, 18 Oct 2015 06:03:48 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions I66 THE MUSICAL TIMES. MARCHI, I886. Notturnein B flcrt. For the Pianoforte. Composed by M. AmbroiseThomas, the composerof " Mignon" and G. J. Rubini. [E. Ascherberger and Co.] of "Hamlet," is engaged upon a new operatic work entitled " Miranda,"which is to be brought out at the WHATEVERpraise is due for writing a melodious and Paris Opera. The libretto is from the pen of M. Jules easily playable little Sketch for the pianoforte, has certainly Barbier,and the suject is borrowedfrom Shakespeare's been earned by the composer of this graceful Notturne. -

Premières Principali All 'Opéra-Comique

Premières principali all ’Opéra-Comique Data Compositore Titolo 30 luglio 1753 Antoine Dauvergne Les troqueurs 26 luglio 1757 Egidio Romualdo Duni Le peintre amoureux de son modèle 9 marzo 1759 François-André Danican Philidor Blaise le savetier 22 agosto 1761 François-André Danican Philidor Le maréchal ferrant 14 settembre 1761 Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny On ne s ’avise jamais de tout 22 novembre 1762 Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny Le roy et le fermier 27 febbraio 1765 François-André Danican Philidor Tom Jones 20 agosto 1768 André Grétry Le Huron 5 gennaio 1769 André Grétry Lucile 6 marzo 1769 Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny Le déserteur 20 settembre 1769 André Grétry Le tableau parlant 16 dicembre 1771 André Grétry Zémire et Azor 12 giugno 1776 André Grétry Les mariages samnites 3 gennaio 1780 André Grétry Aucassin et Nicolette 21 ottobre 1784 André Grétry Richard Coeur-de-lion 4 agosto 1785 Nicolas Dalayrac L ’amant statue 15 maggio 1786 Nicolas Dalayrac Nina, ou La folle par amour 14 gennaio 1789 Nicolas Dalayrac Les deux petits savoyards 4 settembre 1790 Étienne Méhul Euphrosine 15 gennaio 1791 Rodolphe Kreutzer Paolo e Virginia 9 aprile 1791 André Grétry Guglielmo Tell 3 maggio 1792 Étienne Méhul Stratonice 6 maggio 1794 Étienne Méhul Mélidore et Phrosine 11 ottobre 1799 Étienne Méhul Ariodant 23 ottobre 1800 Nicolas Dalayrac Maison à vendre 16 settembre 1801 François-Adrien Boieldieu Le calife de Bagdad 17 maggio 1806 Étienne Méhul Uthal 17 febbraio 1807 Étienne Méhul Joseph 9 maggio 1807 Nicolas Isouard Les rendez-vous bourgeois 22 febbraio -

The German Romantic Movement

The German Romantic Movement Start date 27 March 2020 End date 29 March 2020 Venue Madingley Hall Madingley Cambridge CB23 8AQ Tutor Dr Robert Letellier Course code 1920NRX040 Director of ISP and LL Sarah Ormrod For further information on this Zara Kuckelhaus, Fleur Kerrecoe course, please contact the Lifelong [email protected] or 01223 764637 Learning team To book See: www.ice.cam.ac.uk or telephone 01223 746262 Tutor biography Robert Ignatius Letellier is a lecturer and author and has presented some 30 courses in music, literature and cultural history at ICE since 2002. Educated in Grahamstown, Salzburg, Rome and Jerusalem, he is a member of Trinity College (Cambridge), the Meyerbeer Institute Schloss Thurmau (University of Bayreuth), the Salzburg Centre for Research in the Early English Novel (University of Salzburg) and the Maryvale Institute (Birmingham) as well as a panel tutor at ICE. Robert's publications number over 100 items, including books and articles on the late seventeenth-, eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century novel (particularly the Gothic Novel and Sir Walter Scott), the Bible, and European culture. He has specialized in the Romantic opera, especially the work of Giacomo Meyerbeer (a four-volume English edition of his diaries, critical studies, and two analyses of the operas), the opera-comique and Daniel-François-Esprit Auber, Operetta, the Romantic Ballet and Ludwig Minkus. He has also worked with the BBC, the Royal Opera House, Naxos International and Marston Records, in the researching and preparation of productions. University of Cambridge Institute of Continuing Education, Madingley Hall, Cambridge, CB23 8AQ www.ice.cam.ac.uk Course programme Friday Please plan to arrive between 16:30 and 18:30. -

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas GEORGES BIZET EMI 63633 Carmen Maria Stuarda Paris Opera National Theatre Orchestra; René Bologna Community Theater Orchestra and Duclos Chorus; Jean Pesneaud Childrens Chorus Chorus Georges Prêtre, conductor Richard Bonynge, conductor Maria Callas as Carmen (soprano) Joan Sutherland as Maria Stuarda (soprano) Nicolai Gedda as Don José (tenor) Luciano Pavarotti as Roberto the Earl of Andréa Guiot as Micaëla (soprano) Leicester (tenor) Robert Massard as Escamillo (baritone) Roger Soyer as Giorgio Tolbot (bass) James Morris as Guglielmo Cecil (baritone) EMI 54368 Margreta Elkins as Anna Kennedy (mezzo- GAETANO DONIZETTI soprano) Huguette Tourangeau as Queen Elizabeth Anna Bolena (soprano) London Symphony Orchestra; John Alldis Choir Julius Rudel, conductor DECCA 425 410 Beverly Sills as Anne Boleyn (soprano) Roberto Devereux Paul Plishka as Henry VIII (bass) Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Ambrosian Shirley Verrett as Jane Seymour (mezzo- Opera Chorus soprano) Charles Mackerras, conductor Robert Lloyd as Lord Rochefort (bass) Beverly Sills as Queen Elizabeth (soprano) Stuart Burrows as Lord Percy (tenor) Robert Ilosfalvy as roberto Devereux, the Earl of Patricia Kern as Smeaton (contralto) Essex (tenor) Robert Tear as Harvey (tenor) Peter Glossop as the Duke of Nottingham BRILLIANT 93924 (baritone) Beverly Wolff as Sara, the Duchess of Lucia di Lammermoor Nottingham (mezzo-soprano) RIAS Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala Theater Milan DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 465 964 Herbert von -

Reynaldo Hahn | Chamber Music & Song

Vol . 1 REYNALDO HAHN | CHAMBER MUSIC & SONG JAMES BAILLIEU piano Benjamin Baker violin Tim Lowe cello Adam Newman viola Bartosz Woroch violin FOREWORD TRACK LISTING REYNALDO HAHN (1874–1947) I first came across Reynaldo Hahn through his songs. I loved their unashamed PIANO QUARTET NO.3 IN G MAJOR romanticism, their sentimentality and the effortlessly endearing quality of the 1 i Allegretto moderato 07’25 music. 2 ii Allegro assai 02’11 The popularity of his songs encouraged me to search through Hahn’s lesser- 3 iii Andante 09’48 performed chamber music and present these in a concert series at the Brighton 4 iv Allegro assai 04’50 Festival. The series was a celebration of French music and particularly a study of Benjamin Baker violin Adam Newman viola Tim Lowe cello James Baillieu piano the contrasting musical styles of Poulenc and Hahn. Hahn’s chamber music was 5 À CHLORIS 03’03 so well received that I embarked on this recording project so that it may be Benjamin Baker violin James Baillieu piano enjoyed by a wider audience. This recording shows the incredible scope of Hahn’s music, from the epic drama 6 VOCALISE-ÉTUDE 03’47 Adam Newman viola James Baillieu piano of his piano quintet to a piano quartet full of charm. Especially striking is Hahn’s wonderful gift for melody through the song transcriptions and his extraordinary 7 SI MES VERS AVAIENT DES AILES 02’21 ability to suspend time in the slow movements of his chamber music. Tim Lowe cello James Baillieu piano I am extremely grateful to my colleagues who embarked on this exploration with 8 NOCTURNE IN E-FLAT MAJOR 07’02 me. -

Un Ballo in Maschera

San Francisco Opera Association War Memorial Opera House 2014-2015 Un Ballo in Maschera A Masked Ball (In Italian) Opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi Libretto by Antonio Somma Based on a libretto by Eugene Scribe for Daniel Auber's opera Gustave III, ou Le Bal masque Cast Conductor Nicola Luisotti Count Horn (Sam) Christian Van Horn Count Ribbing (Tom) Scott Conner * Director Jose Maria Condemi Oscar Heidi Stober Costume Designer Gustavus III, King of Sweden (Riccardo) Ramón Vargas John Conklin Count Anckarström (Renato) Thomas Hampson Lighting Designer Brian Mulligan 10/7, 22 Gary Marder Chief Magistrate A.J. Glueckert † Chorus Director Madame Arvidson (Ulrica) Dolora Zajick Ian Robertson Christian (Silvano) Efraín Solís † Choreographer Amelia's Servant Christopher Jackson Lawrence Pech Amelia Anckarström Julianna Di Giacomo * Assistant Conductors Giuseppe Finzi Vito Lombardi * San Francisco Opera debut † Current Adler Fellow Musical Preparation Bryndon Hassman Tamara Sanikidze Place and Time: 1792 in Stockholm, Sweden John Churchwell Jonathan Khuner Fabrizio Corona Prompter Dennis Doubin Supertitles Philip Kuttner Assistant Stage Directors E. Reed Fisher Morgan Robinson Stage Manager Rachel Henneberry Costume Supervisor Jai Alltizer Wig and Makeup Designer Jeanna Parham Saturday, Oct 04 2014, 7:30 PM ACT I Tuesday, Oct 07 2014, 7:30 PM Scene 1: Levee in the king's bedroom Friday, Oct 10 2014, 7:30 PM Scene 2: Madame Arvidson's house on the waterfront Monday, Oct 13 2014, 7:30 PM INTERMISSION Thursday, Oct 16 2014, 7:30 PM ACT II Sunday, Oct 19 2014, 7:30 PM A lonely field Wednesday, Oct 22 2014, 7:30 PM INTERMISSION ACT III Scene 1: Count Anckarström's study Scene 2: The king's box at the opera Scene 3: Inside the Stockhold opera house Sponsors This production is made possible, in part, by the Bernard Osher Endowment Fund and the Thomas Tilton Production Fund. -

French Orientalism in Reynaldo Hahn's Series "Orient" from Le Rossignol Eperdu

Chapter 5 REYNALDO HAHN, HIS FAMILY AND HIS CAREER Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947) was born in Caracas, Venezuela to Carlos Hahn- Dellevie, a Jewish businessman from Hamburg, Germany, and Elena Maria Echenagucia- Ellis, a woman of Spanish descent whose family had been established in Venezuela since the 18th century. Carlos Hahn immigrated to Caracas in the 1840s, and soon rose to wealth through his mercantile business. The family bore twelve children: five sons, five daughters and the other two resulting in infantile deaths. Reynaldo was the youngest of all. 86 Carlos Hahn became a close friend of Venezuelan President Antonio Guzmán- Blanco, who presided in the office between 1870 and 1877, and served as a financial advisor for the president.87 When the Hahn family left Venezuela in 1878, a year after Guzmán-Blanco’s resignation from the office, the former president was able to extend his influence to Paris as Hahn’s family settled down in the new city. Reynaldo was merely three years old. In the same year, the family settled down in Paris, France in a good neighborhood of the 86Bernard Gavoty, Reynaldo Hahn, Le Musicien de La Belle Epoque (Paris: Buchet Chastel, 1997), 19; Mario Milanca Guzmán, Reynaldo Hahn, Caraqueño: Contribución a La Biografía Caraqueña de Reynaldo Hahn Echenagucia (Caracas: Academia Nacional de la Historia, 1989), 19; Patrick O’Connor. "Hahn, Reynaldo." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/ subscriber/article/grove/music/12169 (accessed December 26, 2010). 87Milanca, 54-61. 44 45 Champs-Élysée.88 The future composer had already displayed his inclination to music in Caracas, and once the family settled well enough in Paris, his father Carlos took his 6- year-old son to Opéra-Comique every night, where Reynaldo rode on his father’s shoulder to eagerly catch glimpses of the show. -

Men's Glee Repertoire (2002-2021)

MEN'S GLEE REPERTOIRE (2002-2021) Ain-a That Good News - William Dawson All Ye Saints Be Joyful - Katherine Davis Alleluia - Ralph Manuel Ave Maria - Franz Biebl Ave Maria - Jacob Arcadet Ave Maria - Joan Szymko Ave Maris Stella - arr. Dianne Loomer Beati Mortui - Fexlix Mendelssohn Behold the Lord High Executioner (from The Mikado )- Gilbert and Sullivan Blades of Grass and Pure White Stones -Orin Hatch, Lowell Alexander, Phil Nash/ arr. Keith Christopher Blagoslovi, dushé moyá Ghospoda - Mikhail Mikhailovich Ippolitov-Ivanov Blow Ye Trumpet - Kirke Mechem Bright Morning Stars - Shawn Kirchner Briviba – Ēriks Ešenvalds Brothers Sing On - arr. Howard McKinney Brothers Sing On - Edward Grieg Caledonian Air - arr. James Mullholland Come Sing to Me of Heaven - arr. Aaron McDermid Cornerstone – Shawn Kirchner Coronation Scene (from Boris Goudonov ) - Modest Petrovich Moussorgsky Creator Alme Siderum - Richard Burchard Daemon Irrepit Callidu- György Orbain Der Herr Segne Euch (from Wedding Cantata ) - J. S. Bach Dereva ni Mungu – Jake Runestad Dies Irae - Z. Randall Stroope Dies Irae - Ryan Main Do You Hear the Wind? - Leland B. Sateren Do You Hear What I Hear? - arr. Harry Simeone Down in the Valley - George Mead Duh Tvoy blagi - Pavel Chesnokov Entrance and March of the Peers (from Iolanthe)- Gilbert and Sullivan Five Hebrew Love Songs - Eric Whitacre For Unto Us a Child Is Born (from Messiah) - George Frideric Handel Gaudete - Michael Endlehart Git on Boa'd - arr. Damon H. Dandridge Glory Manger - arr. Jon Washburn Go Down Moses - arr. Moses Hogan God Who Gave Us Life (from Testament of Freedom) - Randall Thompson Hakuna Mungu - Kenyan Folk Song- arr. William McKee Hark! I Hear the Harp Eternal - Craig Carnahan He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands - arr. -

Allusions and Historical Models in Gaston Leroux's the Phantom of the Opera

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 2004 Allusions and Historical Models in Gaston Leroux's The Phantom of the Opera Joy A. Mills Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mills, Joy A., "Allusions and Historical Models in Gaston Leroux's The Phantom of the Opera" (2004). Honors Theses. 83. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/83 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gaston Leroux's 1911 novel, The Phantom of the Opera, has a considerable number of allusions, some of which are accessible to modern American audiences, like references to Romeo and Juilet. Many of the references, however, are very specific to the operatic world or to other somewhat obscure fields. Knowledge of these allusions would greatly enhance the experience of readers of the novel, and would also contribute to their ability to interpret it. Thus my thesis aims to be helpful to those who read The Phantom of the Opera by providing a set of notes, as it were, to explain the allusions, with an emphasis on the extended allusion of the Palais Garnier and the historical models for the heroine, Christine Daae. Notes on Translations At the time of this writing, three English translations are commercially available of The Phantom of the Opera. -

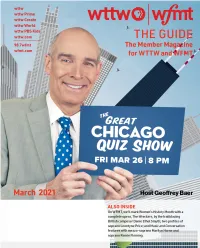

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili.