Lasmigona Decorata) Lea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission Gordon Myers, Executive Director

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission Gordon Myers, Executive Director March 1, 2016 Honorable Jimmy Dixon Honorable Chuck McGrady N.C. House of Representatives N.C. House of Representatives 300 N. Salisbury Street, Room 416B 300 N. Salisbury Street, Room 304 Raleigh, NC 27603-5925 Raleigh, NC 27603-5925 Senator Trudy Wade N.C. Senate 300 N. Salisbury Street, Room 521 Raleigh, NC 27603-5925 Dear Honorables: I am submitting this report to the Environmental Review Committee in fulfillment of the requirements of Section 4.33 of Session Law 2015-286 (H765). As directed, this report includes a review of methods and criteria used by the NC Wildlife Resources Commission on the State protected animal list as defined in G.S. 113-331 and compares them to federal and state agencies in the region. This report also reviews North Carolina policies specific to introduced species along with determining recommendations for improvements to these policies among state and federally listed species as well as nonlisted animals. If you have questions or need additional information, please contact me by phone at (919) 707-0151 or via email at [email protected]. Sincerely, Gordon Myers Executive Director North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission Report on Study Conducted Pursuant to S.L. 2015-286 To the Environmental Review Commission March 1, 2016 Section 4.33 of Session Law 2015-286 (H765) directed the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission (WRC) to “review the methods and criteria by which it adds, removes, or changes the status of animals on the state protected animal list as defined in G.S. -

NAS - Nonindigenous Aquatic Species

green floater (Lasmigona subviridis) - FactSheet Page 1 of 5 NAS - Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Lasmigona subviridis (green floater) Mollusks-Bivalves Native Transplant Michelle Brown - Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History © Lasmigona subviridis Conrad, 1835 Common name: green floater Taxonomy: available through www.itis.gov Identification: This freshwater bivalve exhibits a somewhat compressed to slightly inflated thin shell that is subrhomboid to subovate in shape. The periostracum is yellow, tan, dark green, or brown with dark green rays, and the nacre is white or light blue and sometimes pink near the beaks. The height to width ratio is greater than 0.48 and the beaks are low compared to the line http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=146 1/22/2016 green floater (Lasmigona subviridis) - FactSheet Page 2 of 5 of the hinge. There are two true lamellate pseudocardinal teeth and one relatively small interdental tooth in the left valve, as well as one long and thin lateral tooth in the right valve (Burch 1975, Peckarsky et al. 1993, Bogan 2002). Lasmigona subviridis can grow to 60–65 mm in length (Peckarsky et al. 1993, Bogan 2002). Size: can reach 65 mm Native Range: Lasmigona subviridis was historically found throughout the Atlantic slope drainages in the Hudson, Susquehanna, Potomac, upper Savannah, Kanawha-New, and Cape Fear rivers. However, its range has retracted and it now occurs as disjunct populations in headwaters of coastal and inland rivers and streams of these drainages (Burch 1975, Mills et al. 1993, King et al. 1999, Clayton et al. 2001). Puerto Rico & Alaska Hawaii Guam Saipan Virgin Islands Native range data for this species provided in part by NatureServe http://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=146 1/22/2016 green floater (Lasmigona subviridis) - FactSheet Page 3 of 5 Nonindigenous Occurrences: Lasmigona subviridis was recorded for the first time in the Lake Ontario drainage around 1959 in the Erie Barge Canal at Syracuse and in Chitenango Creek at Kirkville, New York. -

Carolina Heelsplitter (Lasmigona Decorata)

Carolina Heelsplitter (Lasmigona decorata) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation 2012 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Asheville Ecological Services Field Office Asheville, North Carolina 5-YEAR REVIEW Carolina heelsplitter (Lasmigona decorata) I. GENERAL INFORMATION. A. Methodology Used to Complete the Review: This 5-year review was accomplished using pertinent status data obtained from the recovery plan, peer-reviewed scientific publications, unpublished research reports, and experts on this species. Once all known and pertinent data were collected for this species, the status information was compiled and the review was completed by the species’ lead recovery biologist John Fridell in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (Service) Ecological Services Field Office in Asheville, North Carolina, with assistance from biologist Lora Zimmerman, formerly with the Service’s Ecological Services Field Office in Charleston, South Carolina. The Service published a notice in the Federal Register (FR [71 FR 42871]) announcing the 5-year review of the Carolina heelsplitter and requesting new information on the species. A 60-day public comment period was opened. No information about this species was received from the public. A draft of the 5-year review was peer-reviewed by six experts familiar with the Carolina heelsplitter. Comments received were evaluated and incorporated as appropriate. B. Reviewers. Lead Region: Southeast Region, Atlanta, Georgia - Kelly Bibb, 404/679-7132. Lead Field Office: Ecological Services Field Office, Asheville, North Carolina - John Fridell, 828/258-3939, Ext. 225. Cooperating Field Office: Ecological Services Field Office, Charleston, South Carolina - Morgan Wolf, 843/727-4707, Ext. 219. C. Background. 1. -

Surveys and Monitoring for the Hiawatha National Forest: FY 2018 Report

Surveys and Monitoring for the Hiawatha National Forest: FY 2018 Report Prepared By: David L. Cuthrell, Michael J. Monfils, Peter J. Badra, Logan M. Rowe, and William MacKinnon Michigan Natural Features Inventory Michigan State University Extension P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901-3036 Prepared For: Hiawatha National Forest 18 March 2019 MNFI Report No. 2019-10 Suggested Citation: Cuthrell, David L., Michael J. Monfils, Peter J. Badra, Logan M. Rowe, and William MacKinnon. 2019. Surveys and Monitoring for the Hiawatha National Forest: FY 2018 Report. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report No. 2019-10, Lansing, MI. 27 pp. + appendices Copyright 2019 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. MSU Extension programs and ma- terials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover: Large boulder with walking fern, Hiawatha National Forest, July 2018 (photo by Cuthrell). Table of Contents Niagara Habitat Monitoring – for rare snails, ferns and placement of data loggers (East Unit) .......................... 1 Raptor Nest Checks and Productivity Surveys (East and West Units) ................................................................... 2 Rare Plant Surveys (East and West Units) ............................................................................................................. 4 Dwarf bilberry and Northern blue surveys (West Unit) ……………………………..………………………………………………6 State Wide Bumble Bee Surveys (East -

Atlas of the Freshwater Mussels (Unionidae)

1 Atlas of the Freshwater Mussels (Unionidae) (Class Bivalvia: Order Unionoida) Recorded at the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve & State Nature Preserve, Ohio and surrounding watersheds by Robert A. Krebs Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences Cleveland State University Cleveland, Ohio, USA 44115 September 2015 (Revised from 2009) 2 Atlas of the Freshwater Mussels (Unionidae) (Class Bivalvia: Order Unionoida) Recorded at the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve & State Nature Preserve, Ohio, and surrounding watersheds Acknowledgements I thank Dr. David Klarer for providing the stimulus for this project and Kristin Arend for a thorough review of the present revision. The Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve provided housing and some equipment for local surveys while research support was provided by a Research Experiences for Undergraduates award from NSF (DBI 0243878) to B. Michael Walton, by an NOAA fellowship (NA07NOS4200018), and by an EFFRD award from Cleveland State University. Numerous students were instrumental in different aspects of the surveys: Mark Lyons, Trevor Prescott, Erin Steiner, Cal Borden, Louie Rundo, and John Hook. Specimens were collected under Ohio Scientific Collecting Permits 194 (2006), 141 (2007), and 11-101 (2008). The Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve in Ohio is part of the National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS), established by section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act, as amended. Additional information on these preserves and programs is available from the Estuarine Reserves Division, Office for Coastal Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U. S. Department of Commerce, 1305 East West Highway, Silver Spring, MD 20910. -

Manual to the Freshwater Mussels of MD

MMAANNUUAALL OOFF TTHHEE FFRREESSHHWWAATTEERR BBIIVVAALLVVEESS OOFF MMAARRYYLLAANNDD CHESAPEAKE BAY AND WATERSHED PROGRAMS MONITORING AND NON-TIDAL ASSESSMENT CBWP-MANTA- EA-96-03 MANUAL OF THE FRESHWATER BIVALVES OF MARYLAND Prepared By: Arthur Bogan1 and Matthew Ashton2 1North Carolina Museum of Natural Science 11 West Jones Street Raleigh, NC 27601 2 Maryland Department of Natural Resources 580 Taylor Avenue, C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 Prepared For: Maryland Department of Natural Resources Resource Assessment Service Monitoring and Non-Tidal Assessment Division Aquatic Inventory and Monitoring Program 580 Taylor Avenue, C-2 Annapolis, Maryland 21401 February 2016 Table of Contents I. List of maps .................................................................................................................................... 1 Il. List of figures ................................................................................................................................. 1 III. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 IV. Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................ 4 V. Figure of bivalve shell landmarks (fig. 1) .......................................................................................... 5 VI. Glossary of bivalve terms ................................................................................................................ -

Monticello Reservoir Mussel Survey Report

Freshwater Mussel Survey Report In Monticello Reservoir Parr Hydroelectric Project (FERC No. 1894) Fairfield and Newberry Counties, South Carolina Monticello Reservoir Shoreline Habitat Prepared For: South Carolina Electric & Gas Company & Kleinschmidt Associates 204 Caughman Farm Lane, Suite 301 Lexington, SC 29072 April 14, 2016 Prepared by: Three Oaks Engineering 1000 Corporate Drive, Suite 101 Hillsborough, NC 27278 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 2.0 TARGET FEDERALLY PROTECTED SPECIES DESCRIPTION: Carolina Heelsplitter (Lasmigona decorata) .................................................................................. 1 2.1 Species Characteristics ..................................................................................................... 1 2.2 Distribution and Habitat Requirements ............................................................................ 3 2.3 Threats to Species............................................................................................................. 4 2.4 Designated Critical Habitat .............................................................................................. 4 3.0 TARGET PETITIONED FEDERALLY PROTECTED SPECIES DESCRIPTION: Savannah Lilliput (Toxolasma pullus) ............................................................................................ 8 3.1 Species Characteristics .................................................................................................... -

Freshwater Mussels (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Unionida) of Indiana

Freshwater Mussels (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Unionida) of Indiana This list of Indiana's freshwater mussel species was compiled by the state's Nongame Aquatic Biologist based on accepted taxonomic standards and other relevant data. It is periodically reviewed and updated. References used for scientific names are included at the bottom of this list. FAMILY SUBFAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* Margaritiferidae Cumberlandia monodonta Spectaclecase EX, FE Unionidae Anodontinae Alasmidonta marginata Elktoe Alasmidonta viridis Slippershell Mussel SC Anodontoides ferussacianus Cylindrical Papershell Arcidens confragosus Rock Pocketbook Lasmigona complanata White Heelsplitter Lasmigona compressa Creek Heelsplitter Lasmigona costata Flutedshell Pyganodon grandis Giant Floater Simpsonaias ambigua Salamander Mussel SC Strophitus undulatus Creeper Utterbackia imbecillis Paper Pondshell Utterbackiana suborbiculata Flat Floater Ambleminae Actinonaias ligamentina Mucket Amblema plicata Threeridge Cyclonaias nodulata Wartyback Cyclonaias pustulosa Pimpleback Cyclonaias tuberculata Purple Wartyback Cyprogenia stegaria Fanshell SE, FE Ellipsaria lineolata Butterfly Elliptio crassidens Elephantear SC Epioblasma cincinnatiensis Ohio Riffleshell EX Epioblasma flexuosa Leafshell EX Epioblasma obliquata Catspaw EX, FE Epioblasma perobliqua White Catspaw SE, FE Epioblasma personata Round Combshell EX Epioblasma propinqua Tennessee Riffleshell EX Epioblasma rangiana Northern Riffleshell SE, FE Epioblasma sampsonii Wabash Riffleshell EX Epioblasma torulosa Tubercled -

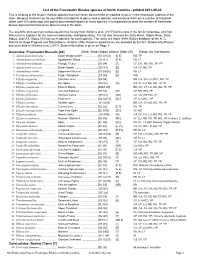

List of the Freshwater Bivalve Species of North Carolina

List of the Freshwater Bivalve species of North Carolina - printed 2021-09-24 This is a listing of the bivalve mollusk species that have been documented or reported to occur in the freshwater systems of the state. Because bivalves can be very difficult to identify to genus and to species, and because there are a number of historical (often over 100 years ago) and poorly documented reports of many species, it is impossible to state the number of freshwater bivalve species that have been documented in the state. The scientific and common names used in this list are from Williams et al. (2017) for the taxa in the family Unionidae, and from NatureServe Explorer for the taxa in Corbiculidae and Sphaeriidae. The list also includes the State Rank, Global Rank, State Status, and U.S. Status (if it has such statuses) for each species. The ranks are those of the Biotics database of the N. C. Natural Heritage Program and NatureServe, October 2016. Ranks in parentheses are provided by the N.C. Biodiversity Project, based on data in Williams et al. (2017). Status information is given on Page 3. Unionidae: Freshwater Mussels [48] [Rank: State Global] [Status: State US] Range (by river basins) 1 Alasmidonta heterodon ................ Dwarf Wedgemussel ................... [S1 G1G2] [E E] NS, TP 2 Alasmidonta raveneliana .............. Appalachian Elktoe ...................... [S1 G1] [E E] FB, LT 3 Alasmidonta undulata ................... Triangle Floater ........................... [S3 G4] [T] CF, CH, NS, RO, TP, YP 4 Alasmidonta varicosa ................... Brook Floater ............................... [S2 G3] [E] CA, CF, NS, YP 5 Alasmidonta viridis ....................... Slippershell Mussel ..................... [S1 G4G5] [E] FB, LT 6 Cyclonaias tuberculata ................ -

Field Guide to the Freshwater Mussels of South Carolina

Field Guide to the Freshwater Mussels of South Carolina South Carolina Department of Natural Resources About this Guide Citation for this publication: Bogan, A. E.1, J. Alderman2, and J. Price. 2008. Field guide to the freshwater mussels of South Carolina. South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Columbia. 43 pages This guide is intended to assist scientists and amateur naturalists with the identification of freshwater mussels in the field. For a more detailed key assisting in the identification of freshwater mussels, see Bogan, A.E. and J. Alderman. 2008. Workbook and key to the freshwater bivalves of South Carolina. Revised Second Edition. The conservation status listed for each mussel species is based upon recommendations listed in Williams, J.D., M.L. Warren Jr., K.S. Cummings, J.L. Harris and R.J. Neves. 1993. Conservation status of the freshwater mussels of the United States and Canada. Fisheries. 18(9):6-22. A note is also made where there is an official state or federal status for the species. Cover Photograph by Ron Ahle Funding for this project was provided by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. 1 North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences 2 Alderman Environmental Services 1 Diversity and Classification Mussels belong to the class Bivalvia within the phylum Mollusca. North American freshwater mussels are members of two families, Unionidae and Margaritiferidae within the order Unionoida. Approximately 300 species of freshwater mussels occur in North America with the vast majority concentrated in the Southeastern United States. Twenty-nine species, all in the family Unionidae, occur in South Carolina. -

Freshwater Bivalves of North Carolina

List of the Freshwater Bivalve species of North Carolina - compiled 2017-11-03 This is a listing of the bivalve mollusk species that have been documented or reported to occur in the freshwater systems of the state. Because bivalves can be very difficult to identify to genus and to species, and because there are a number of historical (often over 100 years ago) and poorly documented reports of many species, it is impossible to state the number of freshwater bivalve species that have been documented in the state. The scientific and common names used in this list are from Williams et al. (2017) for the taxa in the family Unionidae, and from NatureServe Explorer for the taxa in Corbiculidae and Sphaeriidae. The list also includes the State Rank, Global Rank, State Status, and U.S. Status (if it has such statuses) for each species. The ranks are those of the Biotics database of the N. C. Natural Heritage Program and NatureServe, October 2016. Ranks in parentheses are provided by the N.C. Biodiversity Project, based on data in Williams et al. (2017). Status information is given on Page 3. Unionidae: Freshwater Mussels [48] [Rank: State Global] [Status: State US] Range (by river basins) 1 Alasmidonta heterodon ................ Dwarf Wedgemussel ................... [S1 G1G2] [E E] NS, TP 2 Alasmidonta raveneliana .............. Appalachian Elktoe ...................... [S1 G1] [E E] FB, LT 3 Alasmidonta undulata ................... Triangle Floater ........................... [S3 G4] [T FSC] CF, CH, NS, RO, TP, YP 4 Alasmidonta varicosa ................... Brook Floater ............................... [S2 G3] [E FSC] CA, CF, NS, YP 5 Alasmidonta viridis ....................... Slippershell Mussel ..................... [S1 G4G5] [E FSC] FB, LT 6 Cyclonaias tuberculata ................ -

Using Environmental DNA and Macroinvertebrate Biotic Integrity to Inform Conservation Efforts for the Carolina Heelsplitter

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses December 2020 Using Environmental DNA and Macroinvertebrate Biotic Integrity to Inform Conservation Efforts for the Carolina Heelsplitter Benjamin Schmidt Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Schmidt, Benjamin, "Using Environmental DNA and Macroinvertebrate Biotic Integrity to Inform Conservation Efforts for the Carolina Heelsplitter" (2020). All Theses. 3441. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/3441 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING ENVIRONMENTAL DNA AND MACROINVERTEBRATE BIOTIC INTEGRITY TO INFORM CONSERVATION EFFORTS FOR THE CAROLINA HEELSPLITTER A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Wildlife and Fisheries Biology by Benjamin Schmidt December 2020 Accepted by: Dr. Catherine M. Bodinof Jachowski, Committee Chair Dr. Stephen F. Spear Dr. Robert F. Baldwin ABSTRACT The Carolina Heelsplitter (Lasmigona decorata) is a federally endangered freshwater mussel endemic to North and South Carolina, USA. The species has experienced dramatic range-wide declines as a result of habitat fragmentation and water quality deterioration, and the remaining populations are isolated and extremely small. Conservation efforts for the Carolina Heelsplitter have been limited by a lack of knowledge regarding distribution, life history traits, and habitat requirements. Our objectives during this project were to 1. Evaluate the efficacy of an environmental DNA (eDNA) assay to detect the Carolina Heelsplitter and a known host fish, the Bluehead Chub, from stream water samples and 2.