Publication 4684-Aluminum Foil from China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Codes for Types of Cargo, Packages and Packaging Materials

Codes for Types of Cargo, Packages and Packaging Materials for Hazardous Cargo Code Kind Material Category 1A1 1 Drums A Steel non-removable head 1A2 1 Drums A Steel removable head 1B1 1 Drums B Aluminium non-removable head 1B2 1 Drums B Aluminium removable head 1D 1 Drums D Plywood 1G 1 Drums G Fibre 1H1 1 Drums H Plastics non-removable head 1H2 1 Drums H Plastics removable head 2C1 2 Barrels C Wooden bung type 2C2 2 Barrels C Wooden removable head 3A1 3 Jerricans A Steel non-removable head 3A2 3 Jerricans A Steel removable head 3H1 3 Jerricans H Plastics non-removable head 3H2 3 Jerricans H Plastics removable head 4A 4 Boxes A Steel 4B 4 Boxes B Aluminium 4C1 4 Boxes C Natural wood ordinary 4C2 4 Boxes C Natural wood with sift-proof walls 4D 4 Boxes D Plywood 4F 4 Boxes F Reconstituted wood 4G 4 Boxes G Fibreboard 4H1 4 Boxes H Plastics expanded 4H2 4 Boxes H Plastics solid 5H1 5 Bags H Woven plastics without inner lining or coating 5H2 5 Bags H Woven plastics silt-proof 5H3 5 Bags H Woven plastics water resistant 5H4 5 Bags H Plastics film 5L1 5 Bags L Textile without inner lining or coating 5L2 5 Bags L Textile sift-proof 5L3 5 Bags L Textile water resistant 5M1 5 Bags M Paper multiwall 5M2 5 Bags M Paper multiwall, water resistant 6HA1 6 Composite Packaging H Plastics receptacle in steel drum 6HA2 6 Composite Packaging H Plastics receptacle in steel crate or box 6HB 6 Composite Packaging H Plastics receptacle in aluminium drum 6HB2 6 Composite Packaging H Plastics receptacle in aluminium crate or box 6HC 6 Composite Packaging H Plastics -

Handbook for Hazardous Waste Containers

Best Management Practices Handbook for Hazardous Waste Containers HAZARDOUS WASTE HAZARDOUS WASTE HAZARDOUS WASTE ACCUMULATION START DATE CONTENTS HANDLE WITH CARE! CONTAINS HAZARDOUS OR TOXIC WASTES HAZARDOUS WASTE ACCUMULATION HAZARDOUS WASTE HAZARDOUS WASTE START DATE ACCUMULATION ACCUMULATION CONTENTS START DATE START DATE HANDLE WITH CARE! CONTENTS CONTENTS CONTAINS HAZARDOUS OR TOXIC WASTES HANDLE WITH CARE! HANDLE WITH CARE! HAZARDOUS WASTE CONTAINS HAZARDOUS OR TOXIC WASTES CONTAINS HAZARDOUS OR TOXIC WASTES ACCUMULATION START DATE CONTENTS HANDLE WITH CARE! CONTAINS HAZARDOUS OR TOXIC WASTES U.S. EPA Region 6, 1997 FOREWORD This handbook was produced by A.T. Kearney, Inc., under contract to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Region 6, for the Compliance Assurance and Enforcement Division of EPA Region 6. The idea to construct the handbook came from a RCRA workgroup composed of members of several oil and gas companies, the American Petroleum Institute (API), the Texas Mid Continent Oil and Gas Association (TMOGA), EPA, and environmental consulting firms. The RCRA workgroup is one of several workgroups making up the “Refinery Roundtable.” The overall mission of the Refinery Roundtable is to develop methods by which petroleum refineries can achieve better compliance with the environmental regulations. This handbook is to be used solely as guidance and cannot be relied upon to create any rights, substantive or procedural enforceable by any party in litigation with the United States. EPA reserves the right to act at variance with the policies and procedures herein, and to change them at any time without public notice. 2 BMPHWC Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................... 1 2. Best Management Practices for Containers ..................... -

Expertise in Plastics Jerrycans

EXPERTISE IN PLASTICS JERRYCANS 1 / 09-2018 OVERVIEW BUSINESS DIVISIONS KAUTEX INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTS 24 INTENDED USE OF PRODUCTS — MATERIALS AT KAUTEX 26 DATA SHEET FOR THERMOPLASTICS IN GENERAL 28 USAGE INSTRUCTION FOR BOTTLES, JERRYCANS AND CLOSURES 30 2 / 09-2018 CONTENT PRODUCT VOLUME L NECK MATERIAL COLOUR PAGE OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 2–30 HDPE natural colour 4 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 2/2,5/3 DIN 45 HDPE natural colour 5 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 5 DIN 45 HDPE natural colour 6 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 5 DIN 50 HDPE natural colour 7 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 5 DIN 55 HDPE natural colour 8 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 6 DIN 45 and 55 HDPE natural colour 9 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 6–8 DIN 45 HDPE natural colour 10 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 6/8/10 DIN 45 HDPE natural colour 11 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 10 DIN 45 HDPE natural colour 12 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 10 DIN 50 HDPE natural colour 13 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 10 DIN 55 HDPE natural colour 14 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 12 DIN 45 and 55 HDPE natural colour 15 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS SERIES „A“ 15 DIN 60 HDPE natural colour 16 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS SERIES „F“ 15 DIN 60 HDPE natural colour 17 DATA SHEET FOR THERMOPLASTICS OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS SERIES „A“ 20 DIN 60 HDPE natural colour 18 IN GENERAL 28 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS SERIES „F“ 20 DIN 60 and 63 HDPE natural colour 19 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 25 DIN 60 HDPE natural colour 20 OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS 30 DIN 60 HDPE natural colour 21 USAGE INSTRUCTION ACCESSORIES FOR OPTI-RIB® JERRYCANS HDPE white/red/black 22 FOR BOTTLES, JERRYCANS AND CLOSURES 30 DECORATION METHODS 23 09-2018 /3 ® Wide range of approvals OPTI-RIB HDPE JERRYCANS 2 — 30 LITRES 2–30 litres volume Various weight categories Many standard sizes In many standard sizes for a wide range of KAUTEX makes your packing concepts real! industrial applications*, e.g.: We produce cans and bottles accor- §§food ding to your requirements whatever the §§cleaning agents weight, approval, colouring, view strip, pharmaceutical industry embossing, decoration, as well as the §§ type of cap may be. -

DURABLE DRUM LABEL PRODUCTS Reference Guide

Experts in “What If...” DURABLE DRUM LABEL PRODUCTS Reference Guide DURABLE DRUM LABEL PRODUCTS September 2018 Experts in “What If...” GHS Related Changes and Impact on Labeling Chemical drums transporting dangerous materials are subject to stringent safety regulations. Whether that container is being transported overseas, across highways or dispensed into a smaller container and moved from one end of the manufacturing floor to the other; the label on the container must communicate environmental, physical and health hazard information. The Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals (GHS) is a system created to standardize how chemical and hazardous information is communicated in manufacturing facilities and other workplaces. Quite simply, it is a global system for the classification, identification and labeling of chemicals. The objectives of GHS are to increase workplace safety, standardize products internationally and increase productivity. GHS effectively gives the world a common language for chemical identification and the implementation is required by law. The International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code is a global system developed by the International Maritime Organization to enhance the safe transportation of dangerous goods, protect the marine environment and facilitate the free unrestricted movement of dangerous goods. If chemicals being transported require IMDG certification and a self-adhesive label is being used, that label must be BS 5609 certified. GHS defines what information and in what -

Plastic Drum & IBC Packaging Guideline for NFPA Code 30

Plastic Drum & IBC Packaging Guideline For NFPA Code 30 January 1, 2005 This paper was prepared and endorsed by the Plastic Drum Institute (PDI), International Confederation of Plastic Packaging Manufacturers (ICPP), the Rigid Intermediate Bulk Container association (RIBCA) and the Reusable Industrial Packaging Association (RIPA) ¹. This paper provides a guideline for the alignment of the recommended practices in NFPA Code 30 at it relates to the proper use of industrial plastic drums & IBC’s. The 2003 edition of Code 30 was used in preparing this primer. The paper will provide a step-by-step process for users of industrial plastic drums & IBC’s to help in determining if the code applies to their products, and if so how this code is applicable. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) is an international standards organization, with offices in Quincy, MA (USA) that focuses on fire and safety issues. NFPA Code 30 provides (a) definitions and classification of liquids as flammable and combustible, as well as general definitions, (b) reasonable requirements for the safe storage, handling and use of flammable and combustible liquids, and (c) explanatory material used in code development and approval. The NFPA has no power, nor does it undertake, to police or enforce compliance with the codes. NFPA does not list, certify, test or inspect products, designs or installations for code compliance. NFPA does not involve itself with container transportation regulations that are governed by DOT (US Department of Transportation), Transport Canada or the UN Recommendations for the Transport of Dangerous Goods. Contact NFPA to purchase the complete NFPA Code 30 for additional details. -

User Manual Nord Drum

User Manual Nord Drum Part No. 50369 Copyright Clavia DMI AB 2012 Print Edition 1.1 The lightning flash with the arrowhead symbol within CAUTION - ATTENTION an equilateral triangle is intended to alert the user to the RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK presence of uninsulated voltage within the products en- DO NOT OPEN closure that may be of sufficient magnitude to constitute RISQUE DE SHOCK ELECTRIQUE a risk of electric shock to persons. NE PAS OUVRIR Le symbole éclair avec le point de flèche à l´intérieur d´un triangle équilatéral est utilisé pour alerter l´utilisateur de la presence à l´intérieur du coffret de ”voltage dangereux” non isolé d´ampleur CAUTION: TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK suffisante pour constituer un risque d`éléctrocution. DO NOT REMOVE COVER (OR BACK). NO USER SERVICEABLE PARTS INSIDE. REFER SERVICING TO QUALIFIED PERSONNEL. The exclamation mark within an equilateral triangle is intended to alert the user to the presence of important operating and maintenance (servicing) instructions in the ATTENTION:POUR EVITER LES RISQUES DE CHOC ELECTRIQUE, NE PAS ENLEVER LE COUVERCLE. literature accompanying the product. AUCUN ENTRETIEN DE PIECES INTERIEURES PAR L´USAGER. Le point d´exclamation à l´intérieur d´un triangle équilatéral est CONFIER L´ENTRETIEN AU PERSONNEL QUALIFE. employé pour alerter l´utilisateur de la présence d´instructions AVIS: POUR EVITER LES RISQUES D´INCIDENTE OU D´ELECTROCUTION, importantes pour le fonctionnement et l´entretien (service) dans le N´EXPOSEZ PAS CET ARTICLE A LA PLUIE OU L´HUMIDITET. livret d´instructions accompagnant l´appareil. Instructions pertaining to a risk of fire, electric shock or injury to persons. -

Freight Preparation Policy - Part C Freight Preparation Companion

E Centurion Freight Preparation Policy - Part C Freight Preparation Companion Revision Revision No Revision Date Reviewed by Nature of Amendment 0 28/11/2011 M Gale Draft. 1 05/12/2011 M Gale Implemented and distribution of document. 2 20/05/2013 M Gale Addition of further images to assist in packaging by vendors 3 28/08/2013 M Gale Amendment of drum packaging 4 02/09/2013 M Gale Insertion of supplied chain for transport 5 18/11/2014 S Uren Minor Formatting Issue Date: 28/11/2011 Review Date: 18/11/2017 CEN-HSE-POL-042 Page 2 of 33 Revision 5 Freight Preparation Policy - Part C Contents 1 Forward ................................................................................................................................................... 4 2 Commonly Detected Packaging Issues ..................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Pallet Selection .................................................................................................................................................. 5 2.2 Freight Restraint ................................................................................................................................................ 7 3 Dangerous Goods .................................................................................................................................... 9 4 Drums.................................................................................................................................................... 11 4.1 Strapping -

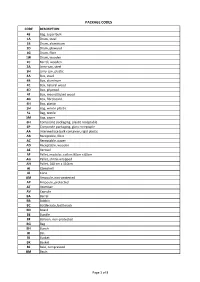

Package Codes

PACKAGE CODES CODE DESCRIPTION 43 Bag, super bulk 1A Drum, steel 1B Drum, aluminium 1D Drum, plywood 1G Drum, fibre 1W Drum, wooden 2C Barrel, wooden 3A Jerry-can, steel 3H Jerry-can, plastic 4A Box, steel 4B Box, aluminum 4C Box, natural wood 4D Box, plywood 4F Box, reconstituted wood 4G Box, fibreboard 4H Box, plastic 5H Bag, woven plastic 5L Bag, textile 5M Bag, paper 6H ComposIte packaging, plastic receptable 6P Composite packaging, glass receptaple AA Intermediate bulk container, rigid plastic AB Receptable, fibre AC Receptable, paper AD Receptable, wooden AE Aerosol AF Pallet, modular, collars 80cm x 60cm AG Pallet, shrink-wrapped AH Pallet, 100 cm x 110cm AI Clamshell AJ Cone AM Ampoule, non-protected AP Ampoule, protected AT Atomiser AV Capsule BA Barrel BB Bobbin BC Bottlecrate, bottlerack BD Board BE Bundle BF Balloon, non-protected BG Bag BH Bunch BI Bin BJ Bucket BK Basket BL Bale, compressed BM Basin Page 1 of 8 PACKAGE CODES CODE DESCRIPTION BN Bale, non-compressed BO Bottle, non-protected, cylindrical BP Balloon, protected BQ Bottle, protected cylindrical BR Bar BS Bottle, non-protected, bulbous BT Bolt BU Butt BV Bottle, protected bulbous BW Box, for liquids BX Box BY Board, in bundle/bunch/truss, BZ Bars, in bundle/bunch/truss CA Can, rectangular CB Beer crate CC Churn CD Can, with handle and spout CE Creel CF Coffer CG Cage CH Chest CI Canister CJ Coffin CK Cask CL Coil CM Collis CN Container not otherwise specified as transport equipment CO Carboy, non-protected CP Carboy, protected CQ Cartdidge CR Crate CS Case CT -

Brochure OPTIMIZED PACKAGING SOLUTIONS FOR

FLUX Sahara ReadyBagTM Bags Structure BEING PRESENT LOCALLY QUALITY Foil (Provides moisture NO NEED FOR PRE-DRYING resistance) Standard plastic ● No risk of moisture pick-up MAKES US MORE AWARE GLOBALLY QUALITY weld sealed QUALITY during overseas transportation or severe humidity storage 100% conditions. RECYCLABLE ● Flux moisture level guaranteed ENVIRONMENT ● savings on as manufactured. treatment cost ● Sandwich structure bag with aluminium foil Plastic ● Environmental (Anti-stretch friendly ● 100% hermetic sealed bag protection) Plastic (Provides protection EUROPE/AFRICA/ME 25 kg BAG 25 kg against 13 Countries TM punctures, NORTH AMERICA 26 Facilities SAHARA READYBAG and lacerations) 22 Facilities 14 Solution Centers 16 Solution Centers ASIA PACIFIC 4 Countries 9 Facilities 5 Solution Centers SAFE TRANSPORT Big Bags Optimize for truck load SAFE TRANSPORT LOGISTIC without stacking = Less risk Optimize for truck for transportation damage LOGISTIC load = Less risk for SOUTH AMERICA NO NEED FOR PRE-DRYING 3 Countries transportation damage 6 Facilities ● No risk of moisture 7 Solution Centers QUALITY pick-up during overseas 100% RECYCLABLE transportation or severe No plastic part humidity storage conditions. ● ● ENVIRONMENT savings on treatment Flux moisture level cost guaranteed as ● Global Headquarters Environmental manufactured. Cleveland, Ohio USA friendly ● Sandwich structure bag with aluminium foil ● 100% hermetic sealed bag 1000/ 1200 kg BULK BAG 1000/ 1200 kg TM BILLION USD REVENUE ACTIVE IN 160 EMPLOYEES WORLDWIDE YEARS OF EXPERIENCE BIG BAG - SAHARA READYBAG 2.6 160COUNTRIES 11 000 120 WORLDWIDE Metal drums ABSOLUT MOISTURE BARRIER FOR SUBMERGED ARC WELDING QUALITY Absolute protection CUSTOMER ASSISTANCE POLICY against moisture pick-up The business of The Lincoln Electric Company® is manufacturing and selling high quality welding equipment, consumables, and cutting equipment. -

Brochure-Schuetz-Pe-Drums-Steel

SCHÜTZ PE DRUMS | STEEL DRUMS As an international supplier of packaging systems we consistently adapt our product range to meet the needs of our customers. SCHÜTZ supplies both global standard drums as well as customised product solutions for regional requirements and specific applications. The global SCHÜTZ drum portfolio: SCHÜTZ F1 tight-head drums 04 | 05 The advantages of the SCHÜTZ F1 06 | 07 SCHÜTZ AUTOMATIC LOCK 08 | 09 SCHÜTZ FOODCERT 10 | 11 SCHÜTZ CLEANCERT 12 | 13 SCHÜTZ S-DS1 open-head drums 14 | 15 SCHÜTZ OC open-head drums 16 | 17 PE drums for special applications 18 | 19 Competence in steel 20 | 21 SCHÜTZ SSF corrugated tight-head drums 22 | 23 SCHÜTZ SDF corrugated open-head drums 24 | 25 Steel drums for special applications 26 | 27 Quality and dependability 28 | 29 Innovative technologies 30 | 31 Safety & originality 32 | 33 Service & logistics 34 | 35 02 | 03 SCHÜTZ F1 tight-head drums. The SCHÜTZ F1 tight-head drum is a true global player. It is produced at all SCHÜTZ sites on all continents to the same design and specifications. Its outstanding characteristics are high dimensional accuracy and exceptional overall performance. These superior characteristics are the result of the patented design and the use of new, highly developed plastics, which further enhance the advantages of the F1 over conventional standard drums: z Better performance in drop test under cold conditions z Greater impact strength at low temperatures z Increased chemical and stress crack resistance z Significantly increased stacking stability SCHÜTZ F1 TIGHT-HEAD DRUMS 220 litres (US) 208 litres Exterior height 935 mm 882 mm Exterior diameter 581 mm 592 mm Type of tight-head opening S70 x 6/S56 x 4 2“buttness x 2“NPS Hazardous goods certification (min.) UN 1H1/Y1.9/200/… UN 1H1/Y1.9/150/… Weight 8.1 kg 8.8 kg The drum types and filling opening models shown here comprise our standard line. -

Accessories for Packaging

Accessories for packaging Pack type Material Closure Simple Advanced Accessory accessories accessories info 5 L Jerrycan PE 51 mm Tap DIN 51 Cat.N° 29548.042 5 L Jerrycan PE 42 mm TAP Cat.N° 29048.098 (by 10 units) 10 L Jerrycan PE 44 mm Cap with tap for 10 L PE container (Technisolv type) Cat.N° 223-0059 10 L Jerrycan PE 51 mm Tap DIN 51 Cat.N° 29548.042 OTAL hand Cat.N° 223-1112 or foot-pump Cat.N° 223-1122 20 L Jerrycan PE 61 mm Tap DIN 61 Cat.N° 29548.043 OTAL hand or foot-pump 25 L Jerrycan PE 61 mm Tap DIN 61 Cat.N° 29548.043 OTAL hand or foot-pump 25 L drum Steel 2" & 3/4" Tap 29548.096 SS Pump Cat.N° 223-1313 + + Tri-Sure (fine thread) adapter barrel joint Cat.N° 223-1249 + Cat.N° 223-1622 antistatic kit Cat.N° 223-1391 25 L drum with liner Steel 2" & 3/4" Tap 29548.096 PP pump Cat.N° 223-1220 + + Mauser adapter Cat.N° 223-1621 barrel joint Cat.N° 223-1262 60 L drum PE 2" & 3/4" Tap 29548.096 PP pump Cat.N° 223-1221 + + Mauser adapter Cat.N° 223-1621 barrel joint Cat.N° 223-1262 Tap 29548.096 PP pump Cat.N° 223-1221 + Tri-Sure (coarse thread) adapter + Cat.N° 223-1620 barrel joint Cat.N° 223-1263 60 L drum with liner Steel 2" Tap 29548.096 PP pump Cat.N° 223-1221 + + Mauser adapter Cat.N° 223-1621 barrel joint Cat.N° 223-1262 200 L drum Steel 2" Tap 29548.096 PP pump Cat.N° 223-1223 + with liner + Mauser adapter Cat.N° 223-1621 barrel joint Cat.N° 223-1262 200 L drum PE 2" Tap 29548.096 PP pump Cat.N° 223-1223 + + Mauser adapter Cat.N° 223-1621 barrel joint Cat.N° 223-1262 ACCESSORIES 200 L drum Steel 2" & 3/4" Tap 29548.096 SS -

1 Introduction

SAFE TRANSFER OF TOXIC LIQUEFIED GASES IGC Doc 188/14/E EUROPEAN INDUSTRIAL GASES ASSOCIATION AISBL AVENUE DES ARTS 3-5 • B – 1210 BRUSSELS Tel: +32 2 217 70 98 • Fax: +32 2 219 85 14 E-mail: [email protected] • Internet: www.eiga.eu Doc 188/14 SAFE TRANSFER OF TOXIC LIQUEFIED GASES PREPARED BY : Joachim Barbe MESSER Giorgio Riccardi SIAD Ramon Castella AIR PRODUCTS Kevin Cleaver THE LINDE GROUP Jon Drakes THE LINDE GROUP Werner Schleser AIR LIQUIDE Pierre Wolfs EIGA Disclaimer All technical publications of EIGA or under EIGA's name, including Codes of practice, Safety procedures and any other technical information contained in such publications were obtained from sources believed to be reliable and are based on technical information and experience currently available from members of EIGA and others at the date of their issuance. While EIGA recommends reference to or use of its publications by its members, such reference to or use of EIGA's publications by its members or third parties are purely voluntary and not binding. Therefore, EIGA or its members make no guarantee of the results and assume no liability or responsibility in connection with the reference to or use of information or suggestions contained in EIGA's publications. EIGA has no control whatsoever as regards, performance or non performance, misinterpretation, proper or improper use of any information or suggestions contained in EIGA's publications by any person or entity (including EIGA members) and EIGA expressly disclaims any liability in connection thereto. EIGA's publications are subject to periodic review and users are cautioned to obtain the latest edition.