Returns to Class Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Materialism, Social Formation and Socio-Spatial Relations : an Essay in Marxist Geography Richard Peet

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 06:28 Cahiers de géographie du Québec Materialism, Social Formation and Socio-Spatial Relations : an Essay in Marxist Geography Richard Peet Volume 22, numéro 56, 1978 Résumé de l'article La géographie marxiste fait partie de la science marxiste et à ce titre elle a URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/021390ar l'autonomie relative des instances qui composent le tout social étudié. Ces DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/021390ar instances, ou les relations qui s'établissent entre elles et qui sont l'objet de la géographie marxiste, sont en premier lieu la relation dialectique entre Aller au sommaire du numéro formations sociales et environnement naturel et en second lieu la dialectique spatiale entre les composantes d'une formation sociale enracinée dans l'espace ou entre des formations sociales dans différentes régions. D'où la nécessité de Éditeur(s) renvoyer aux concepts de mode de production et de formation sociale, de définir et d'illustrer le concept de dialectique spatiale et le développement des Département de géographie de l'Université Laval contradictions dans l'espace. ISSN 0007-9766 (imprimé) 1708-8968 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Peet, R. (1978). Materialism, Social Formation and Socio-Spatial Relations : an Essay in Marxist Geography. Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 22(56), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.7202/021390ar Tous droits réservés © Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 1978 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

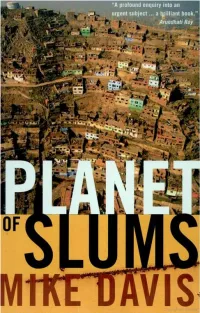

Mike Davis, Planet of Slums

- Planet of Slums • MIKE DAVIS VERSO London • New York formy dar/in) Raisin First published by Verso 2006 © Mike Davis 2006 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 357910 864 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F OEG USA: 180 Varick Street, New York, NY 10014 -4606 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN 1-84467-022-8 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Typeset in Garamond by Andrea Stimpson Printed in the USA Slum, semi-slum, and superslum ... to this has come the evolution of cities. Patrick Geddes1 1 Quoted in Lev.isMumford, The City inHistory: Its Onj,ins,Its Transf ormations, and Its Prospects, New Yo rk 1961, p. 464. Contents 1. The Urban Climacteric 1 2. The Prevalence of Slums 20 3. The Treason of the State 50 4. Illusions of Self-Help 70 5. Haussmann in the Tropics 95 6. Slum Ecology 121 .7. SAPing the Third World 151 ·8. A Surplus Humanity? 174 Epilogue: Down Vietnam Street 199 Acknowledgments 207 Index 209 1 The U rhan Climacteric We live in the age of the city. The city is everything to us - it consumes us, and for that reason we glorify it. Onookome Okomel Sometime in the next year or two, a woman will give birth in the Lagos slum of Ajegunle, a young man will flee his viJlage in west Java for the bright lights of Jakarta, or a farmer will move his impoverished family into one of Lima's innumerable pueblosjovenes . -

Market Socialism As a Distinct Socioeconomic Formation Internal to the Modern Mode of Production

New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry Vol. 5, No. 2 (May 2012) Pp. 20-50 Market Socialism as a Distinct Socioeconomic Formation Internal to the Modern Mode of Production Alberto Gabriele UNCTAD Francesco Schettino University of Rome ABSTRACT: This paper argues that, during the present historical period, only one mode of production is sustainable, which we call the modern mode of production. Nevertheless, there can be (both in theory and in practice) enough differences among the specific forms of modern mode of production prevailing in different countries to justify the identification of distinct socioeconomic formations, one of them being market socialism. In its present stage of evolution, market socialism in China and Vietnam allows for a rapid development of productive forces, but it is seriously flawed from other points of view. We argue that the development of a radically reformed and improved form of market social- ism is far from being an inevitable historical necessity, but constitutes a theoretically plausible and auspicable possibility. KEYWORDS: Marx, Marxism, Mode of Production, Socioeconomic Formation, Socialism, Communism, China, Vietnam Introduction o our view, the correct interpretation of the the most advanced mode of production, capitalism, presently existing market socialism system (MS) was still prevailing only in a few countries. Yet, Marx Tin China and Vietnam requires a new and partly confidently predicted that, thanks to its intrinsic modified utilization of one of Marx’s fundamental superiority and to its inbuilt tendency towards inces- categories, that of mode of production. According to sant expansion, capitalism would eventually embrace Marx, different Modes of Production (MPs) and dif- the whole world. -

Department of Economics

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS Working Paper Problematizing the Global Economy: Financialization and the “Feudalization” of Capital Rajesh Bhattacharya Ian Seda-Irizarry Paper No. 01, Spring 2014, revised 1 Problematizing the Global Economy: Financialization and the “Feudalization” of Capital Rajesh Bhattacharya1 and Ian J. Seda-Irizarry2 Abstract In this essay we note that contemporary debates on financialization revolve around a purported “separation” between finance and production, implying that financial profits expand at the cost of production of real value. Within the literature on financialization, we primarily focus on those contributions that connect financialization to global value-chains, production of knowledge- capital and the significance of rent (ground rent, in Marx’s language) in driving financial strategies of firms, processes that are part of what we call, following others, the feudalization of capital. Building on the contributions of Stephen A. Resnick and Richard D. Wolff, we problematize the categories of capital and capitalism to uncover the capitalocentric premises of these contributions. In our understanding, any discussion of the global economy must recognize a) the simultaneous expansion of capitalist economic space and a non-capitalist “outside” of capital and b) the processes of exclusion (dispossession without proletarianization) in sustaining the capital/non-capital complex. In doing so, one must recognize the significance of both traditional forms of primitive accumulation as well as instances of “new enclosures” in securing rent for dominant financialized firms. Investment in knowledge-capital appears as an increasingly dominant instrument of extraction of rent from both capitalist and non-capitalist producers within a transformed economic geography. In our understanding, such a Marxian analysis renders the separation problem an untenable proposition. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal Can we make sense of knowledge management's tangible rainbow? A radical constructivist alternative Ray, T.; Clegg, S.R. published in Prometheus 2007 DOI (link to publisher) 10.1080/08109020701342249 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Ray, T., & Clegg, S. R. (2007). Can we make sense of knowledge management's tangible rainbow? A radical constructivist alternative. Prometheus, 25(2), 161-185. https://doi.org/10.1080/08109020701342249 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 This article was downloaded by: [Vrije Universiteit, Library] On: 14 June 2011 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number -

Habermas's Theory of Communicative Action Udc: 316.286:316.257

UNIVERSITY OF NIŠ The scientific journal FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Philosophy and Sociology Vol.2, No 6/2, 1999 pp. 217 - 223 Editor of Special issue: Dragoljub B. Đorđević Address: Univerzitetski trg 2, 18000 Niš, YU Tel: +381 18 547-095, Fax: +381 18-547-950 NEW SOCIAL PARADIGM: HABERMAS'S THEORY OF COMMUNICATIVE ACTION UDC: 316.286:316.257 Ljubiša Mitrović Faculty of Philosophy, Niš Abstract. The paper discusses the contribution of J. Habermas to the foundation of a new social paradigm in the form of the communicative action theory. The author first gives a global survey of Habermas's intellectual development, starting from Marx through the critical theory to post-Marxism that Habermas finally left behind since oriented towards convergence and integration of the social action theory, the system theory and the symbolic interactionism theory. Unlike Marx's paradigm of production and social labor as the basic category Marxist theory is built upon, Habermas has built a new paradigm of the communicative action focused upon the communicative mind, communication and rationality as well as the communicative community. The author critically points to the values as well as inner limits of Habermas's theory that reduced a complex and controversial class nature of the society to the "communicative community" thus promoting idealistic worship of the role of the rational discourse. Key words: Communicative Action, Rational Discourse, Communicative Mind, Communicative Community, Post-Marxism The theory of communicative action belongs to the set of modern post-Marxist theories. Its author is Jurgen Habermas (1929-), the German philosopher and sociologist who pertains to the second generation of the Frankfurt philosophical circle. -

Service Workers: Governmentality and Emotion Management

Service Workers: Governmentality and Emotion Management By Hing Ai Yun Abstract That all may be quiet on the shop floor could be a result of governmentality pro- jects. But what lies beneath an appearance of professionalism? I undertook an empirical field study of workers in the service industry to examine contradictory and competing interests of employees and their employers and observed the dy- namic constitution of subjectivity in situations of conflict. Based on a study of 56 service workers, this study first looks at the consensual orientation of workers towards their employment, then discusses a number of common demands required of workers in the service sector and investigates how workers deal with these management demands. My investigation of service workers disclose the internal- ised struggles experienced in their commitment to a prescribed, official image while attempting to maintain, at the same time, an integrous sense of self. By col- lecting stories of actual situations, I am able to show how patterns of emotion management, effectiveness of governmentality project, and agency work together to shape social behaviour in working life. Keywords: Governmentality, emotion management, organismic emotion model Yun, Hing Ai: “Service Workers: Governmentality and Emotion Management”, Culture Unbound, Volume 2, 2010: 311–327. Hosted by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.cultureunbound.ep.liu.se Introduction During the 1980s, terms like “knowledge worker” were bandied about as part of euphoric predictions heralding the “new economy” (Ritzer 1989) and “post indus- trial capitalism” (Heydebrand 1989; Castells 1996). It was proclaimed that knowl- edge and organization, rather than physical capital, are motors of change. -

Managing White-Collar Work: an Operations-Oriented Survey

PRODUCTION AND OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT POMS Vol. 18, No. 1, January–February 2009, pp. 1–32 DOI 10.3401/poms.1080.01002 ISSN 1059-1478|EISSN 1937–5956|09|1801|0001 r 2009 Production and Operations Management Society Managing White-Collar Work: An Operations-Oriented Survey Wallace J. Hopp Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, [email protected] Seyed M. R. Iravani Department of Industrial Engineering and Management Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208 [email protected] Fang Liu Management Science Group, Merrill Lynch, Global Wealth Management, Pennington, NJ 08534, [email protected] lthough white-collar work is of vast importance to the economy, the operations management (OM) literature A has focused largely on traditional blue-collar work. In an effort to stimulate more OM research into the design, control, and management of white-collar work systems, this paper provides a systematic review of disparate streams of research relevant to understanding white-collar work from an operations perspective. Our review classifies research according to its relevance to white-collar work at individual, team, and organizational levels. By examining the literature in the context of this framework, we identify gaps in our understanding of white-collar work that suggest promising research directions. Key words: white-collar work; operations management; survey History: Received: July 2006; Accepted: May 2008, after 2 revisions. 1. Introduction and 21.2%, respectively, from 2004 to 2014, which Operations management (OM) is concerned with the ranks them as the third and first fastest growing processes involved in delivering goods and services occupation categories.1 This trend suggests that future to customers (Hopp and Spearman 2000, Shim and economic growth will depend much more on improv- Siegel 1999). -

Knowledge Worker Creativity and the Role of the Physical Work Environment

Forthcoming in Human Resource Management Knowledge worker creativity and the role of the physical work environment. Jan Dula,b, Canan Ceylanc, Ferdinand Jaspersb b Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. c Department of Business Administration, Uludag University, Bursa, Turkey ABSTRACT The present study examines the effect of the physical work environment on the creativity of knowledge workers, compared with the effects of creative personality and the social-organizational work environment. Based on data from 274 knowledge workers in 27 SMEs, we conclude that creative personality, the social-organizational work environment, and the physical work environment independently affect creative performance. The relative contribution of the physical work environment is smaller than that of the social-organizational work environment, and both contributions are smaller than that of creative personality. The results give support for HR practices that focus on the individual, on the social-organizational work environment, and on the physical work environment in order to enhance knowledge worker creativity. KEYWORDS Human resource management, work environment, creativity, SME, knowledge worker 1 1. Introduction Knowledge workers or “the creative class” (Florida, 2005) are viewed as core to the competitiveness of a firm in a knowledge-based economy (e.g. Lepak & Snell, 2002). These employees are involved in the creation, distribution, or application of knowledge (Davenport, Thomas, & Cantrell, 2002), and the worker’s brains comprise the means of production (Nickols, 2000; Ramírez & Nembhard, 2004). Knowledge workers are the source of original and potentially useful ideas and solutions for a firm’s renewal of products, services, and processes (e.g. Amabile, 1988). -

Revisiting Lenin's Theory of Socialist Revolution on the 150Th Anniversary Of

LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) Blog: Revisiting Lenin’s theory of socialist revolution on the 150th anniversary of his birth Page 1 of 6 Revisiting Lenin’s theory of socialist revolution on the 150th anniversary of his birth Today is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Lenin. To mark the occasion, David Lane presents an assessment of Lenin’s theory of socialist revolution. He writes that while Lenin was correct in his appraisal of the social forces in support of a bourgeois revolution, he provided an incomplete and erroneous analysis of advanced imperial monopoly capitalism. Consequently, the October Revolution of 1917 was a local and regional achievement, but did not have the global revolutionary consequences that he anticipated. It is 150 years since the birth, on 22 April 1870 in Simbirsk (now Ulyanovsk, Russia), of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov: known universally as Lenin. He came from a wealthy family in the social estate of the nobility. His father was an inspector of schools and able to finance the education of his two sons at university. A formative event in Lenin’s life was the execution by hanging of his brother for plotting the assassination of the Tsar in 1887. Lenin himself followed in the tradition of opposition to the autocracy and was expelled from Kazan university for dissident activity and later, in 1897, exiled for three years to Shushenskoye in Siberia. He became an active social-democrat in the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party and was a founder and leader of its Bolshevik wing. Lenin was a leading Marxist theorist of monopoly capitalism and is best known for devising the tactics and strategy for the successful Bolshevik insurrection against the Provisional Government in October 1917. -

Mode of Production and Mode of Exploitation: the Mechanical and the Dialectical'

DjalectiCalAflthropologY 1(1975) 7 — 2 3 © Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam — Printed in The Netherlands MODE OF PRODUCTION AND MODE OF EXPLOITATION: THE MECHANICAL AND THE DIALECTICAL' Eugene E. Ruyle In the social production of their life, men enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will, relations of production which correspond to a definite stage of development of their material produc- tive forces. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which rises a legal and political superstruc- ture and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the social, political and intellectual life process in general. It is not the consciousness of men that deter- mines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.2 The specific economic form, in which unpaid surplus labor is pumped out of the direct producers, determines the relation of rulers and ruled, as it grows immediately out of production itself and in turn reacts upon it as a determining agent. .. It is always the direct relation of the owners of the means of production to the direct producers which reveals the innermost secret, the hidden foundation of the entire social structure.3 In the first of these two passages, Marx in crypto-Marxist bourgeois social science, and appears to be arguing for the sort of techno- then by exploring the possibilities of supple- economic determinism which has become menting the "mode of production" approach increasingly fashionable in bourgeois social with a "mode of exploitation" analysis. -

March 6, 2012 Broad-Based Worker Ownership and Profit Sharing: Can

March 6, 2012 Broad-based Worker Ownership and Profit Sharing: Can These Ideas Work in the Entire Economy? Joseph R. Blasi and Douglas L. Kruse Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations Joseph R. Blasi, a sociologist, is the J. Robert Beyster Professor of Employee Ownership at the Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations and a Research Associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research. He serves as director of the fellowship program on worker ownership at the School. From 1977-1981, he served as a Legislative Assistant in the U.S. House of Representatives with responsibility for worker ownership issues. Douglas L. Kruse, an economist, is a Professor at the Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations and a Research Associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research. He serves as director of the Ph.D. program at SMLR. He is also an associate editor of the British Journal of Industrial Relations. Both co-managed the National Bureau for Economic Research Shared Capitalism Research Project with Richard Freeman of Harvard University. The ideas contained in this article represent solely the views of the authors and do not reflect the views of either Rutgers University or the National Bureau of Economic Research. Abstract This paper examines whether broad-based worker ownership and profit sharing could be expanded to the entire economy. First, it provides a brief overview of the problem and the rationale for the solution proposed. The problem is that capital ownership and capital income are highly concentrated in a very small group in American society.