Beit Din Basics by Rabbi Chaim Jachter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAMAOR Pesach 5775 / April 2015 HAMAOR 3 New Recruits at the Federation

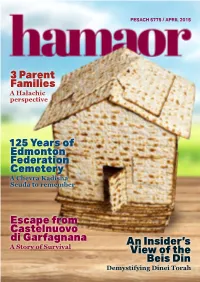

PESACH 5775 / APRIL 2015 3 Parent Families A Halachic perspective 125 Years of Edmonton Federation Cemetery A Chevra Kadisha Seuda to remember Escape from Castelnuovo di Garfagnana An Insider’s A Story of Survival View of the Beis Din Demystifying Dinei Torah hamaor Welcome to a brand new look for HaMaor! Disability, not dependency. I am delighted to introduce When Joel’s parents first learned you to this latest edition. of his cerebral palsy they were sick A feast of articles awaits you. with worry about what his future Within these covers, the President of the Federation 06 might hold. Now, thanks to Jewish informs us of some of the latest developments at the Blind & Disabled, they all enjoy Joel’s organisation. The Rosh Beis Din provides a fascinating independent life in his own mobility examination of a 21st century halachic issue - ‘three parent 18 apartment with 24/7 on site support. babies’. We have an insight into the Seder’s ‘simple son’ and To FinD ouT more abouT how we a feature on the recent Zayin Adar Seuda reflects on some give The giFT oF inDepenDence or To of the Gedolim who are buried at Edmonton cemetery. And make a DonaTion visiT www.jbD.org a restaurant familiar to so many of us looks back on the or call 020 8371 6611 last 30 years. Plus more articles to enjoy after all the preparation for Pesach is over and we can celebrate. My thanks go to all the contributors and especially to Judy Silkoff for her expert input. As ever we welcome your feedback, please feel free to fill in the form on page 43. -

Mishpacha-Article-February-2011.Pdf

HANGING ON BY A FRINGCOLONE:EL MORDECHAI FRIZIS’S MEMBERS COURAG THEEOUS LA SRESPONSET ACT OF THE TRIBE? FOR HIS COUNTRY OPEN MIKE FOR HUCKABEE SWEET SONG OF EMPATHY THE PRESIDENTIAL HOPEFUL ON WHAT FUELED HIS FIFTEENTH TRIP TO ISRAEL A CANDID CONVERSATION WITH SHLOIME DACHS, CHILD OF A “BROKEN HOME” LIFEGUARD AT THE GENE POOL HIS SCREENING PROGRAM HAS SPARED THOUSANDS FROM THE HORROR OF HIS PERSONAL LOSSES. NOW DOR YESHORIM’S RABBI YOSEF EKSTEIN BRAVES THE STEM CELL FRONTIER ON-SITE REPORT RAMALLAHEDUCATOR AND INNOVATOR IN RREALABBI YAAKOV TIME SPITZER CAN THES P.TILLA. FORM LIVA FISCESALLY RSOUNDAV STATE?WEI SSMANDEL’S WORDS familyfirst ISSUE 346 I 5 Adar I 5771 I February 9, 2011 PRICE: NY/NJ $3.99 Out of NY/NJ $4.99 Canada CAD $5.50 Israel NIS 11.90 UK £3.20 INSIDE The Gene Marker's Rabbi Yosef Ekstein of Dor Yeshorim Vowed that No Couple Would Know His Pain Bride When Rabbi Yosef Ekstein’s fourth Tay-Sachs baby was born, he knew he had two options – to fall into crushing despair, or take action. “The Ribono Shel Olam knew I would bury four children before I could take my self-pity and turn it outward,” Rabbi Ekstein says. But he knew nothing about genetics or biology, couldn’t speak English, and didn’t even have a high school diploma. How did this Satmar chassid, a shochet and kashrus supervisor from Argentina, evolve into a leading expert in the field of preventative genetic research, creating an Bride international screening program used by most people in shidduchim today? 34 5 Adar I 5771 2.9.11 35 QUOTES %%% Rachel Ginsberg His father, Rabbi Kalman Eliezer disease and its devastating progression, as Photos: Meir Haltovsky, Ouria Tadmor Ekstein, used to tell him, “You survived by the infant seemed perfect for the first half- a miracle. -

Passover and Firstfruits Chronology

PASSOVER AND FIRSTFRUITS CHRONOLOGY Three Views Dating the Events From Yeshua’s Last Passover to Pentecost by Michael Rudolph Bikkurim: Plan or Coincidence? In the covenant given through Moses, God commanded the Israelites that when they came into the land God had given them, they were to sacrifice a sheaf of their bikkurim1 – their first fruits of the harvest – as a wave offering: “And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, ‘Speak to the children of Israel, and say to them: ‘When you come into the land which I give to you, and reap its harvest, then you shall bring a sheaf of its firstfruits of your harvest to the priest.’” (Leviticus 23:9-10) This was to be done on “the day after the Sabbath,” and was to be accompanied by a burnt offering of an unblemished male lamb: “He shall wave the sheaf before the Lord, to be accepted on your behalf; on the day after the Sabbath the priest shall wave it. And you shall offer on that day, when you wave the sheaf, a male lamb of the first year, without blemish, as a burnt offering to the Lord.” (Leviticus 23:11-12) Then, in the New Covenant Scriptures, we read: “But now Messiah is risen from the dead, and has become the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep. For since by man came death, by man also came the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, even so in Messiah all shall be made alive. But each one in his own order: Messiah the firstfruits, afterward those who are Messiah’s at His coming.” (1 Corinthians 15:20-23) Are the references to “firstfruits” in both the New and Old Covenants coincidental, or are they God’s intricate plan for relating events across the span of centuries? In the sections which follow, this paper demonstrates that they are no coincidence, and that understanding the offering of firstfruits is prophetically important in the dating the events from Yeshua’s last Passover to the arrival of the Holy Spirit. -

Environmental Management of Threatening Government Public Policy Jess Mikeska University of Nebraska-Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research from Business, College of the College of Business Summer 7-2014 Environmental Management of Threatening Government Public Policy Jess Mikeska University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/businessdiss Mikeska, Jess, "Environmental Management of Threatening Government Public Policy" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research from the College of Business. 48. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/businessdiss/48 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Business, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research from the College of Business by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT OF THREATENING GOVERNMENT PUBLIC POLICY by Jess Mikeska A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: Interdepartmental Area of Business (Marketing) Under the Supervision of Professor Leslie Carlson Lincoln, Nebraska July, 2014 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT OF THREATENING GOVERNMENT PUBLIC POLICY Jess Mikeska, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2014 Adviser: Leslie Carlson This dissertation is the first to propose a test of environmental management theory through a reflective, managerial scale, and does so through a public policy lens. It matches 76 managerial respondents’ (17 firms) perceptions of environmental management with objective, secondary data ranging between 2002 and 2014 so as to reflect longitudinal changes in marketplace activities which influence end consumers (e.g., pricing, promotional activity). -

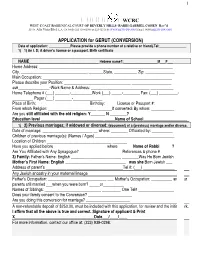

WCRC APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION)

1 WCRC WEST COAST RABBINICAL COURT OF BEVERLY HILLS- RABBI GABRIEL COHEN Rav”d 331 N. Alta Vista Blvd . L.A. CA 90036 323 939-0298 Fax 323 933 3686 WWW.BETH-DIN.ORG Email: INFO@ BETH-DIN.ORG APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION) Date of application: ____________Please provide a phone number of a relative or friend).Tel:_______________ 1) 1) An I. D; A driver’s license or a passport. Birth certificate NAME_______________________ ____________ Hebrew name?:___________________M___F___ Home Address: ________________________________________________________________ City, ________________________________ _______State, ___________ Zip: ______________ Main Occupation: ______________________________________________________________ Please describe your Position: ________________________________ ___________________ ss#_______________-Work Name & Address: ____________________________ ___________ Home Telephone # (___) _______-__________Work (___) _____-________ Fax: (___) _________- __________ Pager (___) ________-______________ Place of Birth: ______________________ ___Birthday:______License or Passport #: ________ From which Religion: _______________________ _______If converted: By whom: ___________ Are you still affiliated with the old religion: Y_______ N ________? Education level ______________________________ _____Name of School_____________________ 1) 2) Previous marriages; if widowed or divorced: (document) of a (previous) marriage and/or divorce. Date of marriage: ________________________ __ where: ________ Officiated by: __________ Children -

Britain's Orthodox Jews in Organ Donor Card Row

UK Britain's Orthodox Jews in organ donor card row By Jerome Taylor, Religious Affairs Correspondent Monday, 24 January 2011 Reuters Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has ruled that national organ donor cards are not permissable, and has advised followers not to carry them Britain’s Orthodox Jews have been plunged into the centre of an angry debate over medical ethics after the Chief Rabbi ruled that Jews should not carry organ donor cards in their current form. London’s Beth Din, which is headed by Lord Jonathan Sacks and is one of Britain’s most influential Orthodox Jewish courts, caused consternation among medical professionals earlier this month when it ruled that national organ donor cards were not permissible under halakha (Jewish law). The decision has now sparked anger from within the Orthodox Jewish community with one prominent Jewish rabbi accusing the London Beth Din of “sentencing people to death”. Judaism encourages selfless acts and almost all rabbinical authorities approve of consensual live organ donorship, such as donating a kidney. But there are disagreements among Orthodox leaders over when post- mortem donation is permissible. Liberal, Reform and many Orthodox schools of Judaism, including Israel’s chief rabbinate, allow organs to be taken from a person when they are brain dead – a condition most doctors consider to determine the point of death. But some Orthodox schools, including London’s Beth Din, have ruled that a person is only dead when their heart and lungs have stopped (cardio-respiratory failure) and forbids the taking of organs from brain dead donors. As the current donor scheme in Britain makes no allowances for such religious preferences, Rabbi Sacks and his fellow judges have advised their followers not to carry cards until changes are made. -

Introduction to the Text

Copyright © 2015, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction to the Text Wendy Laura Belcher This volume introduces and translates the earliest known book-length biography about the life of an African woman: the Gädlä Wälättä ̣eṭrosP . It was written in 1672 in an African language by Africans for Africans about Africans—in particular, about a revered African religious leader who led a successful nonviolent movement against European protocolonialism in Ethiopia. This is the first time this remark- able text has appeared in English. When the Jesuits tried to convert the Ḥabäša peoples of highland Ethiopia from their ancient form of Christianity to Roman Catholicism,1 the seventeenth- century Ḥabäša woman Walatta Petros was among those who fought to retain African Christian beliefs, for which she was elevated to sainthood in the Ethiopian Ortho- dox Täwaḥədo Church. Thirty years after her death, her Ḥabäša disciples (many of whom were women) wrote a vivid and lively book in Gəˁəz (a classical African language) praising her as an adored daughter, the loving friend of women, a de- voted reader, an itinerant preacher, and a radical leader. Walatta Petros must be considered one of the earliest activists against European protocolonialism and the subject of one of the earliest African biographies. The original text is in a distinctive genre called agädl , which is used to tell the inspirational story of a saint’s life, often called a hagiography or hagiobiography (de Porcellet and Garay 2001, 19). -

The WWARN Malaria Data Inventory

The WWARN Malaria Data Inventory - Data Dictionary This is freely available to use as a reference guide for understanding the data variables listed in data files stored in the WWARN Malaria Data Inventory. This file is subject to change, to access the latest version of this file, please visit the WWARN website page here: https://www.wwarn.org/accessing-data. To ask questions relating to the dictionary, please email: [email protected] Please note these important considerations when reviewing the WWARN Data Dictionary: Not every study contributed to WWARN collected all the variables listed in the Data Dictionary In a publication, Data Contributors may have reported collecting data listed in the Data Dictionary, but may not have shared those variables with WWARN Occasionally some studies contain data listed in the Data Dictionary that will require curation before release. The vast majority of data is already fully curated and this only happens for very old data sets or data that may have been shared incrementally. We will let you know after receiving your request if the data requires curation and the time this is expected to take. Variable's Range - Range - Table Name Variable Name Variable Definition Variable's Controlled Terminology Default Unit HIGH value LOW value SUBJECT TABLE This is the WWARN-generated study identifier - it will be the same for all subjects within a Subject sid unique data contribution. Subject site This is the name of the study site for the subject. This is the contributor-provided subject identifier used within the study. This is not unique in the repository as some studies could use the same naming conventions. -

Report of the Regulatory Board of Brit Milah in South Arica

REPORT OF THE REGULATORY BOARD OF BRIT MILAH IN SOUTH AFRICA (“THE REGULATORY BOARD”) 2016 - 2018 1 Background The Regulatory Board of Brit Milah in South Africa was established by Chief Rabbi Dr Warren Goldstein in 2016. The Regulatory Board acts in terms of the delegated authority of the Chief Rabbi and Head of the Beth Din (Court of Jewish Law), Rabbi Moshe Kurtstag. This report covers the activities of the Regulatory Board since inception in April 2016. The number of Britot reported are for the calendar years 2016 and 2017. The Regulatory Board is responsible for: 1.1 Ensuring the very highest standards of care and safety for all infants undergoing a Brit Milah and ensuring that this sacred and holy procedure is conducted according to strict Halachic principles (Jewish law); 1.2 The development of standardised guidelines, policies and procedures to ensure that the highest standards of safety in the performance of Brit Milah are maintained in South Africa; 1.3 Ensuring the appropriate registration, training, accreditation and continuing education of practising Mohalim (plural for Mohel, a person who is trained to perform a circumcision according to Jewish law); 1.4 Maintaining all records of Brit Milahs performed in South Africa; and 1.4 Fully investigating any concerns or complaints raised regarding Brit 1 Milah with the authority to recommend and to institute the appropriate remedial action. The current members of the Regulatory Board are: Dr Richard Friedland (Chairperson). Rabbi Dr Pinhas Zekry (Expert Mohel). Rabbi Anton Klein (Beth Din Representative). Dr Reuven Jacks (Medical Officer). Dr Joseph Spitzer (Mohel and Medical Adviser). -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth -

View the PDF Document

RABBI NORMAN LAMM SEPTEMBER 19, 1970 THE JEWISH CENTER SHABBAT KI TAVO THE FRUITS OF UNITY As one year draws to a close and a new one is about to begin, I bring you greetings from the Holy Land — the land about which it is written (Deut. 11:12) Tl/i) )<- do \ ^ >>l £k 7> mm a land which the Lord thy God cares about; constantly are the eyes of the Lord thy God upon it, from the beginning of the year to the end of the year. It is a beautiful, exciting, lovely, inspiring -- and holy land, even in times of crisis* I tell this to you not to convey in- formation which you did not know before, but rather as a way of mu- tually affirming love and affection for this land of ours. The temper of Israelis has undergone a rather serious change as a result of recent events. Most of them are upset, angry, and dis- appointed in the United States Government. It is true that governments can change their minds, especially on the basis of their own national interest. Sometimes they can even be fickle. But the shocking action of the American Government towards Israel is simply inexcusable. The guarantees that America gave Israel concerning the cease-fire were mere- ly the first of a long list of guarantees in a yet-secret letter that Pres. Nixon sent to Mrs. Meir. When the United States failed to honor those initial commitments, and when, in addition, the State and Defense Departments ridiculed Israel, Israel refused to go any further in what -2- seemed to be an international farce. -

The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha

t HaRofei LeShvurei Leiv: The Contemporary Jewish Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha Senior Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Near Eastern and Judaic Studies Prof. Reuven Kimelman, Advisor Prof. Zvi Zohar, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts by Ezra Cohen December 2018 Accepted with Highest Honors Copyright by Ezra Cohen Committee Members Name: Prof. Reuven Kimelman Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Lynn Kaye Signature: ______________________ Name: Prof. Zvi Zohar Signature: ______________________ Table of Contents A Brief Word & Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………... iii Chapter I: Setting the Stage………………………………………………………………………. 1 a. Why This Thesis is Important Right Now………………………………………... 1 b. Defining Key Terms……………………………………………………………… 4 i. Defining Depression……………………………………………………… 5 ii. Defining Halakha…………………………………………………………. 9 c. A Short History of Depression in Halakhic Literature …………………………. 12 Chapter II: The Contemporary Legal Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Conflict with Halakha…………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 d. Depression & Music Therapy…………………………………………………… 19 e. Depression & Shabbat/Holidays………………………………………………… 28 f. Depression & Abortion…………………………………………………………. 38 g. Depression & Contraception……………………………………………………. 47 h. Depression & Romantic Relationships…………………………………………. 56 i. Depression & Prayer……………………………………………………………. 70 j. Depression &