Accommodation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psaudio Copper

Issue 77 JANUARY 28TH, 2019 Welcome to Copper #77! I hope you had a better view of the much-hyped lunar-eclipse than I did---the combination of clouds and sleep made it a non-event for me. Full moon or no, we're all Bozos on this bus---in the front seat is Larry Schenbeck, who brings us music to counterbalance the blah weather; Dan Schwartz brings us Burritos for lunch; Richard Murison brings us a non-Python Life of Brian; Jay Jay French chats with Giles Martin about the remastered White Album; Roy Hall tells us about an interesting day; Anne E. Johnson looks at lesser-known cuts from Steely Dan's long career; Christian James Hand deconstructs the timeless "Piano Man"; Woody Woodward is back with a piece on seminal blues guitarist Blind Blake; and I consider comfort music, and continue with a Vintage Whine look at Fairchild. Our reviewer friend Vade Forrester brings us his list of guidelines for reviewers. Industry News will return when there's something to write about other than Sears. Copper#77 wraps up with a look at the unthinkable from Charles Rodrigues, and an extraordinary Parting Shot taken in London by new contributor Rich Isaacs. Enjoy, and we’ll see you soon! Cheers, Leebs. Stay Warm TOO MUCH TCHAIKOVSKY Written by Lawrence Schenbeck It’s cold, it’s gray, it’s wet. Time for comfort food: Dvořák and German lieder and tuneful chamber music. No atonal scratching and heaving for a while! No earnest searches after our deepest, darkest emotions. What we need—musically, mind you—is something akin to a Canadian sitcom. -

In Search of Kyle

In search of Kyle MIRANDA VAN GAALEN Copyright © 2018 Miranda van Gaalen The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Edited by Vicki Sauvage and Dr Jin Peh Cover design Anne Luchies DTP Oliver Theisen A catalogue record for this book is available from The National Library of the Netherlands, The Hague Heritage Centre Rozet, Arnhem and The National Library of Australia, Canberra. ISBN 978 90 828 1490 3 NUR 301 / 720 Philamonk About the Author Miranda van Gaalen was born in the Netherlands and has a degree in Business Economics. She lived in Australia from 2000 to 2007. Miranda has extensive knowledge of Feng Shui and loves sports. She co-authored ‘Het Arnhems Kroegenboek’ in 1992, had two short stories published in anthologies in 2012 and was a nominee for the National Book Week Contest in 2014. Miranda lives in Arnhem. To every minority, especially the redheads, may you grow stronger in diversity, this one is for you. ♥ Thank you, Claudia Fischer Natasja Sanches Margaret Pratt Arjen Beltman Charly Stefan ten Have Annet Tomasini Cindy van Roosmalen Beaumaris Book Club my darling brother Mum & Dad Ari Dr Jin Peh Vicki Sauvage! ♥ Supporters Kjeld Kahn Maassen van den Brink Velp BV Guido Steusel Café The Move Flessenwinkel Fischer, Heteren Patisserie Christiaan H&G van Hunen Radio & TV 85 jaar Schoenmakerij ”WIM” Arnhem Boekhandel Hijman Ongerijmd L’Extrémiste Reisboekhandel De Noorderzon Chico’s Place Grand Café Metropole Jansen & de Feijter / Het Colofon Authentiek Sichuan Restaurant in Velp Café Atlanta BeWell Massage & Acupunctuur Café de Wacht Foreword A book with Arnhem as decor? That’s nothing new, witnessing the library that emerged after those ten famous days in September 1944. -

Transcript of Interview

Australians at War Film Archive Harry Cullen (Copp) - Transcript of interview Date of interview: 9th December 2003 http://australiansatwarfilmarchive.unsw.edu.au/archive/1344 Tape 1 00:36 Okay Doug, we’ll make a start now. So if we could start with an introduction to your, your life story, just a summary beginning with where you were born and grew up. Well I was born on the 24th of November, 1918 at Corowa, New South Wales. I think the doctor 01:00 who was in charge of my birth was Dr Barnard. And I was born in the Corowa Private Hospital, and the sister in charge there, was Sister Thompson. And I know that because I’ve met her since. And then I went back to, on the other side of the river to Wahgunyah where we lived, and I grew up there 01:30 on a farm with wheat, growing wheat, sheep and some cattle. Then in, I finished school in, in what, 1933, I think at the age of 15, having got my Intermediate Certificate. And went out to 02:00 be an apprentice winemaker with my uncle who had three vineyards at Rutherglen. The one I went to was called Fairfield, and I stayed there with the manager, boarded with the manager’s wife and worked in the vineyard and in the cellar. So I more or less did my apprenticeship, as a winemaker. Then when, well 02:30 before, about 193-, ’36 I think, I joined the 8th Light Horse Regiment, which was a militia regiment, and it had been commanded by an uncle of mine, Colonel Archie McClorin, who died in Tripoli, Syria in 1918, at the end, just towards the end of the war. -

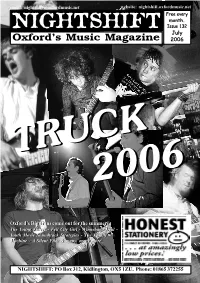

Issue 132.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 132 July Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 TRUCKTRUCK 20062006 Oxford’sOxford’s BigBig GunsGuns comecome outout forfor thethe summer!summer! TheThe YoungYoung KnivesKnives -- FellFell CityCity GirlGirl -- WinnebagoWinnebago DealDeal -- YouthYouth MovieMovie SoundtrackSoundtrack StrategiesStrategies -- TheThe FamilyFamily MachineMachine -- AA SilentSilent FilmFilm && many,many, manymany moremore NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] HELLO EVERYONE, Summer is traditionally a quiet time for live music and this year the World Cup has meant there’s an even greater impact on local gigs, but this month still looks like being an excellent month for music with no less than three local festivals taking place over different weekends. Truck is, of course, the highlight of Oxfordshire’s musical calendar. Now a proper grown-up festival with tickets selling out months ago, Truck continues to provide the most varied and comprehensive showcase of local and international music you’ll find. Our extensive festival preview in this issue touches on just a fraction of the great stuff you’ll be able to hear over the weekend of the 22nd and 23rd. The arrival of Cornbury Festival is a real boost to the county’s summer season. Set in some of the most picturesque countryside in the UK, the second Cornbury Festival boasts an impressive line-up of big names, from Robert Plant and The Pretenders, to Texas and Robyn Hitchcock, as well as some excellent lesser names, and with Truck, the Oxford Folk Festival and Charlbury Riverside Festival organisers also involved, it’s hoped that this year’s event will really put Cornbury on the musical map. -

April - June 2017 Registered Charity No

April - June 2017 Registered Charity No. 1051708 Don’t miss I AM BEAST The Roses’ first live broadcast Pasha Kovalev The Strictly star sashays onto our stage Mobile Intimate drama set in a caravan Film The widest selection in the area The Roses Youth Theatre Recruiting new members now www.rosestheatre.org Proudly supported by Box Office: 01684 295074 Sun Street, Tewkesbury, Glos GL20 5NX Help Us Keep You Up Welcome Live Film Take Part Support Exhibitions Festivals To Date and WIN! April - June 2016 It seems a long time since I wrote Don’t miss July - September 2016 Contents Michael Morpurgo Don’t miss my first introduction to The Roses’ Our Capital Appeal Patron Shakespeare Festival presents War Horse: A summer season of events, Help us to keep you up to date with Only Remembered films and activities brochure back in 2006, and it feels Omid Djalili Symphony To A More top stand up comedy Lost Generation Offers & Discounts 4 English String The world’sRegistered first fullyCharity No. 1051708 holographic production particularly poignant to now be all of the latest hot-off-the-press Orchestra OctoberGlorious - December strings to 2016 Only Fools hail the summer And Boycie Don’t missThe Big Chris An evening with writing my last. March Reminders 5 news and help us to reduce our John Challis Robin HoodBarber & The Band Babes InThe The Jazz Wood Legend Film The widest Our unmissable traditional January - March 2017 selection in family pantomime environmental impact by signing up the area I will be passing the baton of Registered Charity No. -

Australians at War Film Archive Lawrence Date

Australians at War Film Archive Lawrence Date (Fingers) - Transcript of interview Date of interview: 11th March 2004 http://australiansatwarfilmarchive.unsw.edu.au/archive/1561 Tape 1 00:36 We will just start with the brief explanation. My name is Lawrence Edward Date. I was born 20th March 1930 at Allerton Private Hospital in Marrickville Road, Dulwich Hill. The place is still there but it is a community hostel place now. My parents lived in Woodland Street, Marrickville at the time which is the eastern entrance to Enson Park 01:00 rugby league ground in Marrickville now, but at that time it was a tip. They moved from there to live with Dad’s mother in England Avenue Marrickville because the day I was born he lost his job, it was in the Depression. We moved down to Australia Street, Camperdown and we were down there for a couple of years and on my brother’s second birthday on the 11th July 1934 we 01:30 moved down to Woolford Street, Corrimal and I had two more brothers born down there. We all went to Corrimal School and a week before the war started we moved from one side of the street to the other. Mum thought it was a good deal and so did I because I finished up with a room of my own, only a little room but it was mine and we stayed there until twelve months after the war finished and we had to move to Sydney because an 02:00 ex-serviceman had bought the house but it wasn’t big enough for us anyway. -

Garry P Dalrymple Page 44 – an Index to the Book Reviews In

TBS&E #76 – January and February 2018 Revised So, this is the front page and you probably want an Editorial, the disclosure Now in Century Gothic! of stuff I haven’t got round to mentioning Produced by Garry Dalrymple elsewhere in this issue, or something of a as a contribution to ANZAPA biography of how this this issue emerged, mailing No. 302, of the as an Easter weekend rush job. Australian and NZ Amateur At the moment I’m past a few things and Press Association. in the middle of others. The collection of stories from the 2017 Sydney Freecon Postal Address: 1 Eulabah Ave., (‘Eve’s Gift and other stories …’) is out, as Earlwood NSW 2206 a Contributor’s edition and a production edition. I hope to ‘sell’ most copies as Home phone (Best after 7 pm) part of a Cloud funding exercise, i.e. 02 9718-5827 donate $12 to the 2018 Sydney Freecons Email; [email protected] and get a copy posted to an Australian address plus a $5 2018 Paradox Auction book voucher, or donate $2X and get a INDEX to this issue $X 2018 Paradox Auction book voucher. Page 1 – Index and Editorial. Pages 2 to 4 – Brynn Hibbert at the SMSA I have also published a few Trove based February 22, 2018, on Fake Science: Astronomy History booklets, most recently Crooks Cranks & Charlatans. on the Rev. Thomas Roseby and Mars Pages 4 & 5 – the Canterbury and District and the NSW Astronomers, 1877-1945 Historical Society AGM meeting (twice mostly as material for the Skywatcher’s delayed) of February 27, 2018. -

Fights and Fancies: a Search for Australian Magical Realism Caroline Elizabeth Graham University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2012 Fights and fancies: a search for Australian magical realism Caroline Elizabeth Graham University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Graham, Caroline Elizabeth, Fights and fancies: a search for Australian magical realism, Master of Creative Arts (Research) thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2012. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3560 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Fights and fancies: A search for Australian magical realism A collection of short stories and exegesis Submitted in (partial) fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree MASTERS OF CREATIVE ARTS (RESEARCH) from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by CAROLINE ELIZABETH GRAHAM, BA, BJour Bond University 2012 2 CERTIFICATION I, Caroline Elizabeth Graham, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the Masters of Creative Arts (Research), in the Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Caroline Elizabeth Graham, April 17, 2012 3 4 ABSTRACT Fights and Fancies: The Search for Australian Magical Realism attempts to answer the question: Can magical realism successfully translate into the Australian experience? To respond to this question, I have written a collection of nine short stories, titled The Town Time Forgot. Although its approach to the genre is somewhat unconventional, this 50,000 word creative work demonstrates that magical realism can be a valid and successful way to present the Australian story and landscape. -

Cataloguing Songs at the Marx Memorial Library

CITY, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Cataloguing Songs at the Marx Memorial Library Creating an identity for items of musical works within a non- music special collection Sarah E. Crompton October 2019 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MSc in Library and Information Science Supervisor: Dr. Lyn Robinson 1 Abstract What do you do if a song appears in a box of library donations for a non-music library? Send it somewhere else? Songs have text but not like a book has text: to make songs compute with the system, might they need some kind of special ‘music’ treatment? Is there a musician on the team? This dissertation explores reasons why non-music libraries are the best place for some music items, but also why they might sink without trace by being ‘other’ to the main collection. It looks at how defining an ‘identity’ for a minority music collection and relating it to its wider collection could benefit a special collection otherwise known for its non-music subject areas. The methodology parallels an ‘evidence based library and information practice’ (EBLIP) ‘practitioner-research’ perspective to resolve questions. The research progresses through stages of ‘discussion, assessment, reflection, decision, action, revision’ towards eventual findings and practical outcomes. Focusing on songs, ‘people’s songs’ are defined, highlighting their many differences to the formally constructed forms of classical ‘art’ songs. The findings examine ‘people’s songs’ from the perspectives of documentation, information search and retrieval, and concepts of identity. Concepts of ‘borrowing’, ‘branding’, ‘currency’, ‘fix-ity’, ‘oral documents’ and ‘use-intentionality’ scrutinise the question of identity of this particular set of ‘people’s songs’ to its eventual conclusion. -

![Who Ami and Why? - Pressures on the ]Vriting Self](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9601/who-ami-and-why-pressures-on-the-vriting-self-8479601.webp)

Who Ami and Why? - Pressures on the ]Vriting Self

Victoria University WHO AMI AND WHY? - PRESSURES ON THE ]VRITING SELF by Gary Smith (BA, Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Communication, Language and Cultoral Smdies Victoria University March 2004 FTS THESIS A828.409 SMI 30001008090864 Smith, Gary (Gary Francis) Who am I and why? : pressures on the writing self m Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to Wendy, whose omnipresent love, patience and understanding were the warm gardenbeds in which both writer and writing could winter and spring. IV Acknowledgements I would Hke to thank the postgraduate department of Victoria University for accepting my candidature and granting me the scholarship that made this project possible. I am especially indebted to my principal supervisor, Professor John McLaren, for his invaluable advice and assistance in aU aspects of the thesis, and for his patience and persistence in working through some of the more problematic stages of this PhD project. Thanks also go to my co-supervisor. Doctor Ian Syson for his assistance and advice when I needed it, and to Judith Rodriguez for helpful conversations. I would also like to thank those who've helped me keep my personal equilibrium — sometimes with advice and feedback on poems and stories, but mostiy for their friendship and encouragement at tougher moments - thank you Max & Peg, Patrick & GiU, Jo, Mary. Table of Contents Section Page Title Page i Declaration ii Dedication Hi Acknowledgements iv Abstract vi 1: Introduction 1 2: Snapshots of Broken Things 32 The Stories 33 The Poems 167 3: Critical Essays 213 4: Conclusions 286 Bibliographj 315 Appendix ?>z2. -

Freier Download BA 68 Als

BAD 68 ALCHEMY 1 BA‘s Favourites 2010 COSA BRAVA – RAGGED ATLAS (INTAKT) FIRST MEETING – CUT THE ROPE (LIBRA) DANIEL KAHN AND THE PAINTED BIRD – LOST CAUSES (ORIENTE MUSIC) LITTLE WOMEN – THROAT (AUM FIDELITY) MASTER MUSICIANS OF BUKKAKE – TOTEM ONE (CONSPIRACY) MOSTLY OTHER PEOPLE DO THE KILLING – FORTY FORT (HOT CUP!) NICHELODEON – IL GIOCO DEL SILENZIO (LIZARD) GHEDALIA TAZARTES – ANTE-MORTEM (HINTERZIMMER) UNIVERS ZERO – CLIVAGES (CUNEIFORM) WEASEL WALTER - MARY HALVORSON - PETER EVANS – ELECTRIC FRUIT (THIRSTY EAR) www.discogs.com/lists/Bad-Alchemystic-Music-BAs-FAVOURITE-THINGS-1965-1977/13998 www.discogs.com/lists/Bad-Alchemystic-Music-EVERGREENS-FÜR-MORGEN-1978-1992/13999 www.discogs.com/lists/Bad-Alchemystic-Music-THE-ANTI-POP-CONTINUUM-1993-2004/14054 As bad-alchemystic as the world should be: www.myspace.com/b_lange 2 Freakshow: SON ESSENTIEL Und vielleicht kann dann ja so eine Empfindung entstehen: Irgendwie fehlt den ande- ren Körpern etwas, dass also plötzlich der Körper, der nicht der Norm entspricht, als vollendet gesehen wird. Lieder wie von Raimund Hoghe getanzt, Sätze wie auf Artauds Nervenwaage abgewo- gen. Die Musik an diesem Mittwochabend, dem 27.10.2010, im Würzburger Cairo scheint von dem Demiurgen zu stammen, dessen Spleen auch Rhinozeros, Giraffe, Oka- pi und Schnabeltier entsprangen. Frauen haben Filets hinter den Schläfen, die See- pferdchen gleichen. Pascal Godjikian spricht diesen Satz deutsch, ernst wie Max. Über- haupt sind die Surrealismen und Absurditäten von LA SOCIÉTÉ DES TIMIDES À LA PARADE DES OISEAUX, kurz La STPO, verkoppelt mit einem Ernst, den es nicht schert, ob das Theatralische ihrer Aufführung einer Norm entspricht. Godjikian ist kein Showtalent, alles an ihm ist echt, er entblößt sich und seine Phantasiewelt mit dem vol- len Risiko, abzustürzen, zieht sich am eigenen Hosenbund von den Abgründen des All- tags zurück. -

1996.05.15-Hot-Press.Pdf

Authority could applaud, as Gay Byrne cosied up to Dolores onLate the Late. On the surface, The Cranberries seem the most Irish of all our suc Great Series To Cut Out And Keep cesses. Yet dig deeper and the evidence appears to contradict that N A to Z series in which a lusty squad of Hot Press lexicographers scour the dictionaries, ency comforting view. For really, The Cranberries may be the most isolated clopaedias and history books of the world to unearth the precise and formal terminologies for some of all our famous Seamuses and Siles. A unusual, not so unusual and very fucking unusual sexual practices. Though they are still based in Limerick, The Cranberries are curiously detached from the wider Irish music community. Delete a spell support Apart from affording one a rare opportunity to talk dirty while simultaneously sounding intelli ing Hot House Flowers in America and there’s scant record of them gent, the listing of these terms of endearment should serve as a source of warm reassurance for having any allies or friends among other major Irish musicians. Despite many readers. In other words, if it has an official name then you can’t be the only person to have sharing the same label and following the same America-first path to thought about doing it. success, relations with U2 were patchy and diplomatic, at least until O ’Riordan recently teamed up with Bono and Pavarotti on Warthe Child benefit. Nor did they appear to associate with the wider Irish pop-culture com Balinese Marriage: Bali is an island of one million inhabitants off the coast of Java.