Reclaiming the Right to Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ME 1 Workbook

Math Explorations Part 1 Workbook 2013 Edition Hiroko Warshauer Terry McCabe Max Warshauer Published by Stipes Publishing L.L.C. 204 W. University Ave. Champaign, Illinois 61820 Copyright © 2013 TEXAS Mathworks Publisher: Stipes Authors: Hiroko Warshauer, Terry McCabe, and Max Warshauer Project Coordinator: Hiroko Warshauer Project Designer: Namakshi P. Kant Contributing Teachers: Alexandra Eusebi, Krystal Gaeta, Diana Garza, Denise Girardeau, Sandra Guerra, Melinda Kniseley, Melissa Lara, Terry Luis, Barbara Marques, Pat Padron, Rolinda Park, Eduardo Reyna, Patricia Serviere, Elizabeth Tate, Edna Tolento, Lorenz Villa, Amanda Voigt, Amy Warshauer, Elizabeth Weed. Editorial Assistance, Problem Contributions, and Technical Support: Sam Baethge, Ashley Beach, Molly Bending, Tina Briley, Cheyenne Crooks, Rachel Carroll, Edward Early, Michelle Frei, Vanessa Garcia, Kristen Gould, Marie Graham, Michael Kellerman, Rhonda Martinez, Cody Patterson, Karen Vazquez, Alexander White, Sally Williams, Luis Sosa. Sponsors: RGK Foundation, Kodosky Foundation, Meadows Foundation, and Intel Foundation Copyright © 2013 Texas State University – Mathworks. All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-938858-03-1. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Texas Mathworks. Printed in the United States of America. For information on obtaining permission for use of material in this work, please submit written request to Texas Mathworks, 601 University Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666. Fax your request to 512-245-1469, or email to [email protected]. MATH EXPLORATIONS PART 1 WORKBOOK table of contents CH. 1 EXPLORING INTEGERS 1 Section 1.1 Building Number Lines .............................................. 1 Section 1.2 Less Than and Greater Than ..................................... -

ENG 350 Summer12

ENG 350: THE HISTORY OF HIP-HOP With your host, Dr. Russell A. Potter, a.k.a. Professa RAp Monday - Thursday, 6:30-8:30, Craig-Lee 252 http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ In its rise to the top of the American popular music scene, Hip-hop has taken on all comers, and issued beatdown after beatdown. Yet how many of its fans today know the origins of the music? Sure, people might have heard something of Afrika Bambaataa or Grandmaster Flash, but how about the Last Poets or Grandmaster CAZ? For this class, we’ve booked a ride on the wayback machine which will take us all the way back to Hip-hop’s precursors, including the Blues, Calypso, Ska, and West African griots. From there, we’ll trace its roots and routes through the ‘parties in the park’ in the late 1970’s, the emergence of political Hip-hop with Public Enemy and KRS-One, the turn towards “gangsta” style in the 1990’s, and on into the current pantheon of rappers. Along the way, we’ll take a closer look at the essential elements of Hip-hop culture, including Breaking (breakdancing), Writing (graffiti), and Rapping, with a special look at the past and future of turntablism and digital sampling. Our two required textbook are Bradley and DuBois’s Anthology of Rap (Yale University Press) and Neal and Forman’s That's the Joint: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader are both available at the RIC campus store. Films shown in part or in whole will include Bamboozled, Style Wars, The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, Wild Style, and Zebrahead; there will is also a course blog with a discussion board and a wide array of links to audio and text resources at http://350hiphop.blogspot.com/ WRITTEN WORK: An informal response to our readings and listenings is due each week on the blog. -

The Outkast Class

R. Bradley OutKast Class Syllabus OutKast Course Description and Objectives Pre-requisite: ENGL1102 Preferred Pre-requisites: ENGL2300, AADS1102 In 1995, Atlanta, GA duo OutKast attended the Source Hip Hop Awards where they won the award for Best New Duo. Mostly attended by bi-coastal rappers and hip hop enthusiasts, OutKast was booed off the stage. OutKast member Andre Benjamin, clearly frustrated, emphatically declared what is now known as the rallying cry for young black southerners: “the south got something to say.” For this course, we will use OutKast’s body of work as a case study questioning how we recognize race and identity in the American south after the Civil Rights Movement. Using a variety of post-Civil Rights era texts including film, fiction, criticism, and music, students will interrogate OutKast’s music as the foundation of what the instructor theorizes as “the hip hop south,” the southern black social-cultural landscape in place over the last 25 years. Objectives 1. To develop and utilize a multidisciplinary critical framework to successfully engage with conversations revolving around contemporary identity politics and (southern) popular culture 2. To challenge students to engage with unfamiliar texts, cultural expressions, and language in order to learn how to be socially and culturally sensitive and aware of modes of expression outside of their own experiences. 3. To develop research and writing skills to create and/or improve one’s scholarly voice and others via the following assignments: • Critical Listening Journals • Creative or Critical Final Project **Explicit Content Statement (courtesy of Dr. Treva B. Lindsey)** Over the course of the semester students will Be introduced to texts that may Be explicit in nature (i.e. -

Plaintiff Must Prove Service on Motion to Vacate Default Judgment by Erin Louise Palmer , Litigation News Contributing Editor – May 12, 2015

Plaintiff Must Prove Service on Motion to Vacate Default Judgment By Erin Louise Palmer , Litigation News Contributing Editor – May 12, 2015 Service by certified mail is insufficient to satisfy the plaintiff’s burden in a motion to vacate a default judgment, according to the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania . In Myers v. Moore , the district court granted the defendants’ motion to vacate a default judgment of more than $1 million where the plaintiff failed to demonstrate that the defendants had actual knowledge of the lawsuit and where the plaintiff failed to establish that she properly served the complaint on defendants or their authorized agents. Observers question how a plaintiff would satisfy these evidentiary hurdles. Plaintiff Awarded $1 Million Default Judgment The lawsuit arises out of a stage-diving incident at a music venue in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. During a performance, the lead singer of the band Fishbone, Angelo C. Moore, dove into the crowd and knocked over the plaintiff, causing her serious injuries. The plaintiff sued Moore, John Noorwood Fisher (Fishbone’s bass player), Fishbone, Fishbone’s manager, and other parties associated with the venue for negligence and civil conspiracy in producing the concert and failing to warn the audience that the concert would feature stage diving. The plaintiff also sued Moore, Fisher, and Fishbone for assault and battery. After the plaintiff reached settlements with some of the defendants, the court dismissed the plaintiff’s claims against the non-settling defendants, including Moore and Fisher. The plaintiff brought another action on February 3, 2012, against the non-settling defendants for negligence, civil conspiracy, and assault and battery. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Big Black Pigpile Mp3, Flac, Wma

Big Black Pigpile mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Pigpile Country: US Released: 1992 Style: Industrial, Noise MP3 version RAR size: 1119 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1815 mb WMA version RAR size: 1934 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 569 Other Formats: MMF VOX ADX MP2 XM MP4 AIFF Tracklist A1 Fists Of Love A2 L Dopa A3 Passing Complexion A4 Dead Billy A5 Cables A6 Bad Penny B1 Pavement Saw B2 Kerosene B3 Steelworker B4 Pigeon Kill B5 Fish Fry B6 Jordan, Minnesota Companies, etc. Record Company – Southern Studios Ltd. Pressed By – MPO Recorded At – Hammersmith Clarendon Notes Recorded at the Hammersmith Clarendon, London, England in Summer 1987. White label in plain white sleeve with New Release letter from Southern Studios, London which has typed tracklist Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout Etchings Side A): MPO TG 81 A1 "A Dearth of Jon Spencer or What?" Matrix / Runout (Runout Etchings Side B): MPO TG 81 B1 "Please Increase Playback Volume 2db" Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album) Touch And Go TG81 US 1992 TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album, TP) Touch And Go TG81 US 1992 TG81C Big Black Pigpile (Cass) Touch And Go TG81C US 1992 TG81 Big Black Pigpile (LP, Album, RP) Touch And Go TG81 US Unknown SENTO YU-1 Big Black Pigpile (CD, Album) Sento SENTO YU-1 Japan 1992 Related Music albums to Pigpile by Big Black Clash, The - (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais Alexander O'Neal - Live At The Hammersmith Apollo - London Balaam And The Angel - Live At The Clarendon Venom - Fuckin' Hell At Hammersmith The Human League - London Hammersmith Palais 22.5.80 Killing Joke - Live At The Hammersmith Apollo 16.10.2010 Volume 1 Motörhead - No Sleep 'Til Hammersmith Danzig - Die Die My Darling Big Black - Songs About Fucking Venom - Live In Hammersmith Odeon London 08.10.85. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

BAM Announces November Bamcafé Live Lineup

BAM announces November BAMcafé Live lineup No cover! No minimum! Friday and Saturday nights Brooklyn, NY/October 8, 2015—Now in its 16th season, BAMcafé Live (30 Lafayette Avenue)—the performance series curated by Darrell M. McNeill, associate producer, music programming— announced its November lineup featuring rock, jazz, R&B, world, pop, and more. BAMcafé Live events have no cover charge and no drink minimum. For information and updates, call 718.636.4100 or visit BAM.org. Friday & Saturday night schedule Fri, Nov 6 at 9pm—Audra Isadora Sat, Nov 7 at 9pm—Tammy Scheffer Sextet Fri, Nov 13 at 10pm—God’s Unruly Friends Sat, Nov 14 at 10pm— REBELLUM - Burnt Sugar Arkestra’s Avant Splinter Cell Fri, Nov 20 at 9pm—Awesome Tapes From Africa (DJ Set) Presented in conjunction with World Music Institute Sat, Nov 21 at 9pm—Gato Loco Presented in conjunction with World Music Institute Fri, Nov 27 and Sat, Nov 28 at 9pm—Akim Funk Buddha’s Hip-Hop Holiday Host: Phillip Andry House DJ: DJ Idlemind “The Appropriate Agent” For press inquiries, contact Baha Ebrahimzadeh at 718.636.4129 x 1 or [email protected]. About the artists Fri, Nov 6 at 9pm Audra Isadora Drawing inspiration from iconoclasts like Kate Bush and David Bowie, Audra Isadora combines outré glam eccentricity with irresistible pop hooks. Her seductive, powerhouse contralto propels synth-heavy dance-floor rave-ups and soaring, down-tempo ballads alike, all wrapped in offbeat arrangements that feature oboe lines played by Isadora. Sat, Nov 7 at 9pm Tammy Scheffer Sextet Tammy Scheffer’s crystalline voice draws listeners into her imaginative jazz experiments. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

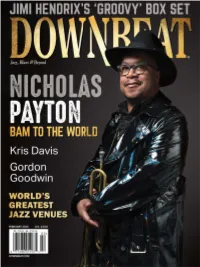

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Honeymoon Suite & Prism

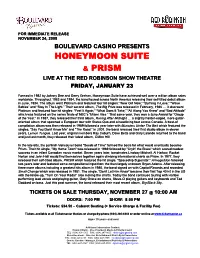

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NOVEMBER 24, 2008 BOULEVARD CASINO PRESENTS HONEYMOON SUITE & PRISM LIVE AT THE RED ROBINSON SHOW THEATRE FRIDAY, JANUARY 23 Formed in 1982 by Johnny Dee and Derry Grehan, Honeymoon Suite have achieved well over a million album sales worldwide. Throughout 1983 and 1984, the band toured across North America releasing their self-titled debut album in June, 1984. The album went Platinum and featured four hit singles: “New Girl Now,” “Burning In Love,” “Wave Babies” and “Stay In The Light.” Their second album, The Big Prize was released in February, 1986 … it also went Platinum and featured four hit singles: “Feel It Again,” “What Does It Take,” “All Along You Knew” and “Bad Attitude” which was featured on the series finale of NBC’s “Miami Vice.” That same year, they won a Juno Award for “Group of the Year.” In 1987, they released their third album, Racing After Midnight … a slightly harder-edged, more guitar- oriented album that spawned a European tour with Status Quo and a headlining tour across Canada. A best-of compilation album was then released in 1989 followed a year later with Monsters Under The Bed which featured the singles, “Say You Don’t Know Me” and “The Road.” In 2001, the band released their first studio album in eleven years, Lemon Tongue. Last year, original members Ray Coburn, Dave Betts and Gary Lalonde returned to the band and just last month, they released their latest album, Clifton Hill. In the late 60s, the punkish Vancouver band "Seeds of Time" formed the basis for what would eventually become Prism. -

Gaslightpdffinal.Pdf

Credits. Book Layout and Design: Miah Jeffra Cover Artwork: Pseudodocumentation: Broken Glass by David DiMichele, Courtesy of Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco ISBN: 978-0-692-33821-6 The Writers Retreat for Emerging LGBTQ Voices is made possible, in part, by a generous contribution by Amazon.com Gaslight Vol. 1 No. 1 2014 Gaslight is published once yearly in Los Angeles, California Gaslight is exclusively a publication of recipients of the Lambda Literary Foundation's Emerging Voices Fellowship. All correspondence may be addressed to 5482 Wilshire Boulevard #1595 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Details at www.lambdaliterary.org. Contents Director's Note . 9 Editor's Note . 11 Lisa Galloway / Epitaph ..................................13 / Hives ....................................16 Jane Blunschi / Snapdragon ................................18 Miah Jeffra / Coffee Spilled ................................31 Victor Vazquez / Keiki ....................................35 Christina Quintana / A Slip of Moon ........................36 Morgan M Page / Cruelty .................................51 Wayne Johns / Where Your Children Are ......................53 Wo Chan / Our Majesties at Michael's Craft Shop ..............66 / [and I, thirty thousand feet in the air, pop] ...........67 / Sonnet by Lamplight ............................68 Yana Calou / Mortars ....................................69 Hope Thompson/ Sharp in the Dark .........................74 Yuska Lutfi Tuanakotta / Mother and Son Go Shopping ..........82 Megan McHugh / I Don't Need to Talk -

Izona S Art: First Album to Be Like a Jackson 5 Thing in the Audience's Eyes That Album (Straight up Pop Without Just Makes the Shows Fun

For the week of Aug. Sept. 10-16 The Lumberjack Happenings A G pseo f Goldfinger Mon. - Thurs. - 5:15, 7:40 H ar kin v Flagstaff I uxurv 11 gets its She’s Sc Lovefy (R) 4650 N. Highway 89 774-4700 (1:30Sat. & Sun. only), 5,7A (9 p.m. Fri. & Sat. only) > I r tyiii The Gamei R) Mon. - Thurs. - 5A 7:30 p.m. hang ups Cl I a-ih. Sat. A Sun. only),!, 2:25,4.5:20, 7,8:10 & (12:40 a.m Fri. & Sal. only). H ercules (G) Flagstaff Mall Cinema out into (10:55 Sat.A Sun. only), 4:20A 9:00 4650 N. Highway 89 52 ^4 5 5 5 Excess Baggage (PG-13) * Jeffrey Bell (10:10 SaL A Sun. only), 1:30,4:30,7:30A 10 Cop L an d (PG-13) Happenings Editor (12:35 a.m. Fri.& Sat. only) (1:45 Sat. - Mon. only), 4:30,7,9:10 & (4:30 p.m. inofifi firm Fri. & Sal. csnly ) the open H oodlum (R) Mon.- Thurs. - 4:45,7p.m. 12:45,3:50,7:20A 10:40 p.m. A ir B ud (R) Four guys from Los AngelesDoubt and the Skeletones G J . Ja n e (R) are ready togive Phoenix the finstopped by to help out. ( 10:30 Sat. A Sun. only), 1:10.4:10, 7:10, 4:45 p.m.A (2:15 Sat.A Sun. only) ger. The Goldfinger "Working with Angelo Moore 10:10 & (i 2:45 a.m.