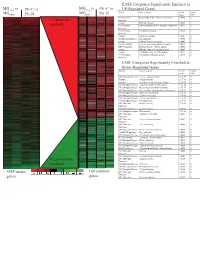

Figure S1. GO Analysis in the Treated Versus HBV(+) Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C8cc08685k1.Pdf

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for ChemComm. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2018 Supporting Information Minimalist Linkers Suitable for Irreversible Inhibitors in Simultaneous Proteome Profiling, Live-Cell Imaging and Drug Screening Cuiping Guo,Yu Chang, Xin Wang, Chengqian Zhang, Piliang Hao*, Ke Ding and Zhengqiu Li* School of Pharmacy, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China 510632 *Corresponding author ([email protected]) 1. General Information All chemicals were purchased from commercial vendors and used without further purification, unless indicated otherwise. All reactions requiring anhydrous conditions were carried out under argon or nitrogen atmosphere using oven-dried glassware. AR-grade solvents were used for all reactions. Reaction progress was monitored by TLC on pre-coated silica plates (Merck 60 F254 nm, 0.25 µm) and spots were visualized by UV, iodine or other suitable stains. Flash column chromatography was carried out using silica gel (Qingdao Ocean). All NMR spectra (1H-NMR, 13C-NMR) were recorded on Bruker 300 MHz/400 MHz NMR spectrometers. Chemical shifts were reported in parts per million (ppm) referenced with respect to appropriate internal standards or residual solvent peaks (CDCl3 = 7.26 ppm, DMSO-d6 = 2.50 ppm). The following abbreviations were used in reporting spectra, br s (broad singlet), s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), m (multiplet), dd (doublet of doublets). Mass spectra were obtained on Agilent LC-ESI-MS system. All analytical HPLC were carried out on Agilent system. Water with 0.1% TFA and acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA were used as eluents and the flow rate was 0.5 mL/min. -

The Rise and Fall of the Bovine Corpus Luteum

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC Theses & Dissertations Graduate Studies Spring 5-6-2017 The Rise and Fall of the Bovine Corpus Luteum Heather Talbott University of Nebraska Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd Part of the Biochemistry Commons, Molecular Biology Commons, and the Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons Recommended Citation Talbott, Heather, "The Rise and Fall of the Bovine Corpus Luteum" (2017). Theses & Dissertations. 207. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd/207 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BOVINE CORPUS LUTEUM by Heather Talbott A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the University of Nebraska Graduate College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Graduate Program Under the Supervision of Professor John S. Davis University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, Nebraska May, 2017 Supervisory Committee: Carol A. Casey, Ph.D. Andrea S. Cupp, Ph.D. Parmender P. Mehta, Ph.D. Justin L. Mott, Ph.D. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation was supported by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Pre-doctoral award; University of Nebraska Medical Center Graduate Student Assistantship; University of Nebraska Medical Center Exceptional Incoming Graduate Student Award; the VA Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System Department of Veterans Affairs; and The Olson Center for Women’s Health, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nebraska Medical Center. -

Analysis of Trans Esnps Infers Regulatory Network Architecture

Analysis of trans eSNPs infers regulatory network architecture Anat Kreimer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Anat Kreimer All rights reserved ABSTRACT Analysis of trans eSNPs infers regulatory network architecture Anat Kreimer eSNPs are genetic variants associated with transcript expression levels. The characteristics of such variants highlight their importance and present a unique opportunity for studying gene regulation. eSNPs affect most genes and their cell type specificity can shed light on different processes that are activated in each cell. They can identify functional variants by connecting SNPs that are implicated in disease to a molecular mechanism. Examining eSNPs that are associated with distal genes can provide insights regarding the inference of regulatory networks but also presents challenges due to the high statistical burden of multiple testing. Such association studies allow: simultaneous investigation of many gene expression phenotypes without assuming any prior knowledge and identification of unknown regulators of gene expression while uncovering directionality. This thesis will focus on such distal eSNPs to map regulatory interactions between different loci and expose the architecture of the regulatory network defined by such interactions. We develop novel computational approaches and apply them to genetics-genomics data in human. We go beyond pairwise interactions to define network motifs, including regulatory modules and bi-fan structures, showing them to be prevalent in real data and exposing distinct attributes of such arrangements. We project eSNP associations onto a protein-protein interaction network to expose topological properties of eSNPs and their targets and highlight different modes of distal regulation. -

Reprogramming of Trna Modifications Controls the Oxidative Stress Response by Codon-Biased Translation of Proteins

Reprogramming of tRNA modifications controls the oxidative stress response by codon-biased translation of proteins The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Chan, Clement T.Y. et al. “Reprogramming of tRNA Modifications Controls the Oxidative Stress Response by Codon-biased Translation of Proteins.” Nature Communications 3 (2012): 937. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1938 Publisher Nature Publishing Group Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/76775 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. Reprogramming of tRNA modifications controls the oxidative stress response by codon-biased translation of proteins Clement T.Y. Chan,1,2 Yan Ling Joy Pang,1 Wenjun Deng,1 I. Ramesh Babu,1 Madhu Dyavaiah,3 Thomas J. Begley3 and Peter C. Dedon1,4* 1Department of Biological Engineering, 2Department of Chemistry and 4Center for Environmental Health Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139; 3College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering, University at Albany, SUNY, Albany, NY 12203 * Corresponding author: PCD, Department of Biological Engineering, NE47-277, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139; tel 617-253-8017; fax 617-324-7554; email [email protected] 2 ABSTRACT Selective translation of survival proteins is an important facet of cellular stress response. We recently demonstrated that this translational control involves a stress-specific reprogramming of modified ribonucleosides in tRNA. -

Allele-Specific Expression of Ribosomal Protein Genes in Interspecific Hybrid Catfish

Allele-specific Expression of Ribosomal Protein Genes in Interspecific Hybrid Catfish by Ailu Chen A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama August 1, 2015 Keywords: catfish, interspecific hybrids, allele-specific expression, ribosomal protein Copyright 2015 by Ailu Chen Approved by Zhanjiang Liu, Chair, Professor, School of Fisheries, Aquaculture and Aquatic Sciences Nannan Liu, Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology Eric Peatman, Associate Professor, School of Fisheries, Aquaculture and Aquatic Sciences Aaron M. Rashotte, Associate Professor, Biological Sciences Abstract Interspecific hybridization results in a vast reservoir of allelic variations, which may potentially contribute to phenotypical enhancement in the hybrids. Whether the allelic variations are related to the downstream phenotypic differences of interspecific hybrid is still an open question. The recently developed genome-wide allele-specific approaches that harness high- throughput sequencing technology allow direct quantification of allelic variations and gene expression patterns. In this work, I investigated allele-specific expression (ASE) pattern using RNA-Seq datasets generated from interspecific catfish hybrids. The objective of the study is to determine the ASE genes and pathways in which they are involved. Specifically, my study investigated ASE-SNPs, ASE-genes, parent-of-origins of ASE allele and how ASE would possibly contribute to heterosis. My data showed that ASE was operating in the interspecific catfish system. Of the 66,251 and 177,841 SNPs identified from the datasets of the liver and gill, 5,420 (8.2%) and 13,390 (7.5%) SNPs were identified as significant ASE-SNPs, respectively. -

Acetyl-Coa Synthetase 3 Promotes Bladder Cancer Cell Growth Under Metabolic Stress Jianhao Zhang1, Hongjian Duan1, Zhipeng Feng1,Xinweihan1 and Chaohui Gu2

Zhang et al. Oncogenesis (2020) 9:46 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41389-020-0230-3 Oncogenesis ARTICLE Open Access Acetyl-CoA synthetase 3 promotes bladder cancer cell growth under metabolic stress Jianhao Zhang1, Hongjian Duan1, Zhipeng Feng1,XinweiHan1 and Chaohui Gu2 Abstract Cancer cells adapt to nutrient-deprived tumor microenvironment during progression via regulating the level and function of metabolic enzymes. Acetyl-coenzyme A (AcCoA) is a key metabolic intermediate that is crucial for cancer cell metabolism, especially under metabolic stress. It is of special significance to decipher the role acetyl-CoA synthetase short chain family (ACSS) in cancer cells confronting metabolic stress. Here we analyzed the generation of lipogenic AcCoA in bladder cancer cells under metabolic stress and found that in bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA) cells, the proportion of lipogenic AcCoA generated from glucose were largely reduced under metabolic stress. Our results revealed that ACSS3 was responsible for lipogenic AcCoA synthesis in BLCA cells under metabolic stress. Interestingly, we found that ACSS3 was required for acetate utilization and histone acetylation. Moreover, our data illustrated that ACSS3 promoted BLCA cell growth. In addition, through analyzing clinical samples, we found that both mRNA and protein levels of ACSS3 were dramatically upregulated in BLCA samples in comparison with adjacent controls and BLCA patients with lower ACSS3 expression were entitled with longer overall survival. Our data revealed an oncogenic role of ACSS3 via regulating AcCoA generation in BLCA and provided a promising target in metabolic pathway for BLCA treatment. 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; Introduction acetyl-CoA synthetase short chain family (ACSS), which In cancer cells, considerable number of metabolic ligates acetate and CoA6. -

Seq2pathway Vignette

seq2pathway Vignette Bin Wang, Xinan Holly Yang, Arjun Kinstlick May 19, 2021 Contents 1 Abstract 1 2 Package Installation 2 3 runseq2pathway 2 4 Two main functions 3 4.1 seq2gene . .3 4.1.1 seq2gene flowchart . .3 4.1.2 runseq2gene inputs/parameters . .5 4.1.3 runseq2gene outputs . .8 4.2 gene2pathway . 10 4.2.1 gene2pathway flowchart . 11 4.2.2 gene2pathway test inputs/parameters . 11 4.2.3 gene2pathway test outputs . 12 5 Examples 13 5.1 ChIP-seq data analysis . 13 5.1.1 Map ChIP-seq enriched peaks to genes using runseq2gene .................... 13 5.1.2 Discover enriched GO terms using gene2pathway_test with gene scores . 15 5.1.3 Discover enriched GO terms using Fisher's Exact test without gene scores . 17 5.1.4 Add description for genes . 20 5.2 RNA-seq data analysis . 20 6 R environment session 23 1 Abstract Seq2pathway is a novel computational tool to analyze functional gene-sets (including signaling pathways) using variable next-generation sequencing data[1]. Integral to this tool are the \seq2gene" and \gene2pathway" components in series that infer a quantitative pathway-level profile for each sample. The seq2gene function assigns phenotype-associated significance of genomic regions to gene-level scores, where the significance could be p-values of SNPs or point mutations, protein-binding affinity, or transcriptional expression level. The seq2gene function has the feasibility to assign non-exon regions to a range of neighboring genes besides the nearest one, thus facilitating the study of functional non-coding elements[2]. Then the gene2pathway summarizes gene-level measurements to pathway-level scores, comparing the quantity of significance for gene members within a pathway with those outside a pathway. -

Identification and Characterization of TPRKB Dependency in TP53 Deficient Cancers

Identification and Characterization of TPRKB Dependency in TP53 Deficient Cancers. by Kelly Kennaley A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Molecular and Cellular Pathology) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Zaneta Nikolovska-Coleska, Co-Chair Adjunct Associate Professor Scott A. Tomlins, Co-Chair Associate Professor Eric R. Fearon Associate Professor Alexey I. Nesvizhskii Kelly R. Kennaley [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-2439-9020 © Kelly R. Kennaley 2019 Acknowledgements I have immeasurable gratitude for the unwavering support and guidance I received throughout my dissertation. First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis advisor and mentor Dr. Scott Tomlins for entrusting me with a challenging, interesting, and impactful project. He taught me how to drive a project forward through set-backs, ask the important questions, and always consider the impact of my work. I’m truly appreciative for his commitment to ensuring that I would get the most from my graduate education. I am also grateful to the many members of the Tomlins lab that made it the supportive, collaborative, and educational environment that it was. I would like to give special thanks to those I’ve worked closely with on this project, particularly Dr. Moloy Goswami for his mentorship, Lei Lucy Wang, Dr. Sumin Han, and undergraduate students Bhavneet Singh, Travis Weiss, and Myles Barlow. I am also grateful for the support of my thesis committee, Dr. Eric Fearon, Dr. Alexey Nesvizhskii, and my co-mentor Dr. Zaneta Nikolovska-Coleska, who have offered guidance and critical evaluation since project inception. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Systems Analysis Implicates WAVE2&Nbsp

JACC: BASIC TO TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE VOL.5,NO.4,2020 ª 2020 THE AUTHORS. PUBLISHED BY ELSEVIER ON BEHALF OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY FOUNDATION. THIS IS AN OPEN ACCESS ARTICLE UNDER THE CC BY-NC-ND LICENSE (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). PRECLINICAL RESEARCH Systems Analysis Implicates WAVE2 Complex in the Pathogenesis of Developmental Left-Sided Obstructive Heart Defects a b b b Jonathan J. Edwards, MD, Andrew D. Rouillard, PHD, Nicolas F. Fernandez, PHD, Zichen Wang, PHD, b c d d Alexander Lachmann, PHD, Sunita S. Shankaran, PHD, Brent W. Bisgrove, PHD, Bradley Demarest, MS, e f g h Nahid Turan, PHD, Deepak Srivastava, MD, Daniel Bernstein, MD, John Deanfield, MD, h i j k Alessandro Giardini, MD, PHD, George Porter, MD, PHD, Richard Kim, MD, Amy E. Roberts, MD, k l m m,n Jane W. Newburger, MD, MPH, Elizabeth Goldmuntz, MD, Martina Brueckner, MD, Richard P. Lifton, MD, PHD, o,p,q r,s t d Christine E. Seidman, MD, Wendy K. Chung, MD, PHD, Martin Tristani-Firouzi, MD, H. Joseph Yost, PHD, b u,v Avi Ma’ayan, PHD, Bruce D. Gelb, MD VISUAL ABSTRACT Edwards, J.J. et al. J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Trans Science. 2020;5(4):376–86. ISSN 2452-302X https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.01.012 JACC: BASIC TO TRANSLATIONALSCIENCEVOL.5,NO.4,2020 Edwards et al. 377 APRIL 2020:376– 86 WAVE2 Complex in LVOTO HIGHLIGHTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS Combining CHD phenotype–driven gene set enrichment and CRISPR knockdown screening in zebrafish is an effective approach to identifying novel CHD genes. -

Supplementary Materials

1 Supplementary Materials: Supplemental Figure 1. Gene expression profiles of kidneys in the Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice. (A) A heat map of microarray data show the genes that significantly changed up to 2 fold compared between Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice (N=4 mice per group; p<0.05). Data show in log2 (sample/wild-type). 2 Supplemental Figure 2. Sting signaling is essential for immuno-phenotypes of the Fcgr2b-/-lupus mice. (A-C) Flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes isolated from wild-type, Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice at the age of 6-7 months (N= 13-14 per group). Data shown in the percentage of (A) CD4+ ICOS+ cells, (B) B220+ I-Ab+ cells and (C) CD138+ cells. Data show as mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001). 3 Supplemental Figure 3. Phenotypes of Sting activated dendritic cells. (A) Representative of western blot analysis from immunoprecipitation with Sting of Fcgr2b-/- mice (N= 4). The band was shown in STING protein of activated BMDC with DMXAA at 0, 3 and 6 hr. and phosphorylation of STING at Ser357. (B) Mass spectra of phosphorylation of STING at Ser357 of activated BMDC from Fcgr2b-/- mice after stimulated with DMXAA for 3 hour and followed by immunoprecipitation with STING. (C) Sting-activated BMDC were co-cultured with LYN inhibitor PP2 and analyzed by flow cytometry, which showed the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IAb expressing DC (N = 3 mice per group). 4 Supplemental Table 1. Lists of up and down of regulated proteins Accession No. -

Supplement 1 Microarray Studies

EASE Categories Significantly Enriched in vs MG vs vs MGC4-2 Pt1-C vs C4-2 Pt1-C UP-Regulated Genes MG System Gene Category EASE Global MGRWV Pt1-N RWV Pt1-N Score FDR GO Molecular Extracellular matrix cellular construction 0.0008 0 110 genes up- Function Interpro EGF-like domain 0.0009 0 regulated GO Molecular Oxidoreductase activity\ acting on single dono 0.0015 0 Function GO Molecular Calcium ion binding 0.0018 0 Function Interpro Laminin-G domain 0.0025 0 GO Biological Process Cell Adhesion 0.0045 0 Interpro Collagen Triple helix repeat 0.0047 0 KEGG pathway Complement and coagulation cascades 0.0053 0 KEGG pathway Immune System – Homo sapiens 0.0053 0 Interpro Fibrillar collagen C-terminal domain 0.0062 0 Interpro Calcium-binding EGF-like domain 0.0077 0 GO Molecular Cell adhesion molecule activity 0.0105 0 Function EASE Categories Significantly Enriched in Down-Regulated Genes System Gene Category EASE Global Score FDR GO Biological Process Copper ion homeostasis 2.5E-09 0 Interpro Metallothionein 6.1E-08 0 Interpro Vertebrate metallothionein, Family 1 6.1E-08 0 GO Biological Process Transition metal ion homeostasis 8.5E-08 0 GO Biological Process Heavy metal sensitivity/resistance 1.9E-07 0 GO Biological Process Di-, tri-valent inorganic cation homeostasis 6.3E-07 0 GO Biological Process Metal ion homeostasis 6.3E-07 0 GO Biological Process Cation homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Biological Process Cell ion homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Biological Process Ion homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Molecular Helicase activity 2.3E-06 0 Function GO Biological