Compiling a Bilingual Glossary of Terminology Related to Singing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Categorization of Vocal Fry in Running Speech

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Honors Projects Honors College Fall 12-2019 Categorization of Vocal Fry in Running Speech Katherine Proctor [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Laboratory and Basic Science Research Commons Repository Citation Proctor, Katherine, "Categorization of Vocal Fry in Running Speech" (2019). Honors Projects. 549. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects/549 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. CATEGORIZATION OF VOCAL FRY IN RUNNING SPEECH CATEGORIZATION OF VOCAL FRY IN RUNNING SPEECH KATHERINE PROCTOR HONORS PROJECT Submitted to the Honors College at Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with UNIVERSITY HONORS 12/9/19 Dr. Ronald Scherer, Communication Sciences and Disorders, College of Health and Human Services, Advisor Dr. Katherine Meizel, Musicology/Ethnomusicology, College of Musical Arts, Advisor 1 CATEGORIZATION OF VOCAL FRY IN RUNNING SPEECH INTRODUCTION The concept of a vocal register has been defined by Hollien (1974) as “a series or range of consecutive frequencies that can be produced with nearly identical voice quality.” There are three different vocal registers in speech production according to Hollien (1974). These registers are: loft, which is the highest of the three, and could be described perceptually as the “falsetto” range; modal, which is the middle range and is evident in “normal” speech production; and pulse, the lowest range of phonation that is characterized by popping, pulsing sounds. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Vocal Tract Dimensions and Vocal Fold Vibratory Characteristics Title of Professional Singers of Different Singing Voice Types

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HKU Scholars Hub Vocal tract dimensions and vocal fold vibratory characteristics Title of professional singers of different singing voice types Author(s) Chan, Ka-u; 陳加裕 Chan, K. [陳加裕]. (2012). Vocal tract dimensions and vocal fold vibratory characteristics of professional singers of different Citation singing voice types. (Thesis). University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR. Issued Date 2012 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/237890 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.; The Rights author retains all proprietary rights, (such as patent rights) and the right to use in future works. Running head: VOCAL TRACT AND VOICE SOURCE CHARACTERISTICS 1 Vocal tract dimensions and vocal fold vibratory characteristics of professional singers of different singing voice types Chan, Ka U Edith A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Science (Speech and Hearing Sciences), The University of Hong Kong, June 30, 2012. VOCAL TRACT AND VOICE SOURCE CHARACTERISTICS 2 Abstract This study aimed to examine the relationship between different singing voice types and their vocal fold vibratory characteristics and vocal tract dimensions. A total of 19 tenors, 10 baritones, 29 sopranos, and 4 mezzo-sopranos participated in the study. Electroglottography (EGG) was used to measure the vocal fold vibratory characteristics, based on which parameters including open quotient (Oq) and fundamental frequency (F0) were derived. During the experiment, the participants sang the song “Happy Birthday” with constant loudness level and at the most comfortable pitch level. -

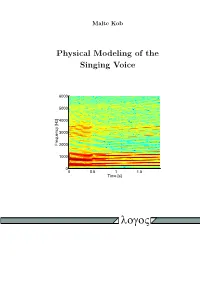

Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice

Malte Kob Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice 6000 5000 4000 3000 Frequency [Hz] 2000 1000 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 Time [s] logoV PHYSICAL MODELING OF THE SINGING VOICE Von der FakulÄat furÄ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik der Rheinisch-WestfÄalischen Technischen Hochschule Aachen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER INGENIEURWISSENSCHAFTEN genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Diplom-Ingenieur Malte Kob aus Hamburg Berichter: UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr. rer. nat. Michael VorlÄander UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr.-Ing. Peter Vary Professor Dr.-Ing. JuÄrgen Meyer Tag der muÄndlichen PruÄfung: 18. Juni 2002 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfuÄgbar. Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Kob, Malte: Physical modeling of the singing voice / vorgelegt von Malte Kob. - Berlin : Logos-Verl., 2002 Zugl.: Aachen, Techn. Hochsch., Diss., 2002 ISBN 3-89722-997-8 c Copyright Logos Verlag Berlin 2002 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. ISBN 3-89722-997-8 Logos Verlag Berlin Comeniushof, Gubener Str. 47, 10243 Berlin Tel.: +49 030 42 85 10 90 Fax: +49 030 42 85 10 92 INTERNET: http://www.logos-verlag.de ii Meinen Eltern. iii Contents Abstract { Zusammenfassung vii Introduction 1 1 The singer 3 1.1 Voice signal . 4 1.1.1 Harmonic structure . 5 1.1.2 Pitch and amplitude . 6 1.1.3 Harmonics and noise . 7 1.1.4 Choir sound . 8 1.2 Singing styles . 9 1.2.1 Registers . 9 1.2.2 Overtone singing . 10 1.3 Discussion . 11 2 Vocal folds 13 2.1 Biomechanics . 13 2.2 Vocal fold models . 16 2.2.1 Two-mass models . 17 2.2.2 Other models . -

Why Do Singers Sing in the Way They

Why do singers sing in the way they do? Why, for example, is western classical singing so different from pop singing? How is it that Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballe could sing together? These are the kinds of questions which John Potter, a singer of international repute and himself the master of many styles, poses in this fascinating book, which is effectively a history of singing style. He finds the reasons to be primarily ideological rather than specifically musical. His book identifies particular historical 'moments of change' in singing technique and style, and relates these to a three-stage theory of style based on the relationship of singing to text. There is a substantial section on meaning in singing, and a discussion of how the transmission of meaning is enabled or inhibited by different varieties of style or technique. VOCAL AUTHORITY VOCAL AUTHORITY Singing style and ideology JOHN POTTER CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 IRP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, United Kingdom 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1998 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1998 Typeset in Baskerville 11 /12^ pt [ c E] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Potter, John, tenor. -

The Composer's Guide to the Tuba

THE COMPOSER’S GUIDE TO THE TUBA: CREATING A NEW RESOURCE ON THE CAPABILITIES OF THE TUBA FAMILY Aaron Michael Hynds A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2019 Committee: David Saltzman, Advisor Marco Nardone Graduate Faculty Representative Mikel Kuehn Andrew Pelletier © 2019 Aaron Michael Hynds All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Saltzman, Advisor The solo repertoire of the tuba and euphonium has grown exponentially since the middle of the 20th century, due in large part to the pioneering work of several artist-performers on those instruments. These performers sought out and collaborated directly with composers, helping to produce works that sensibly and musically used the tuba and euphonium. However, not every composer who wishes to write for the tuba and euphonium has access to world-class tubists and euphonists, and the body of available literature concerning the capabilities of the tuba family is both small in number and lacking in comprehensiveness. This document seeks to remedy this situation by producing a comprehensive and accessible guide on the capabilities of the tuba family. An analysis of the currently-available materials concerning the tuba family will give direction on the structure and content of this new guide, as will the dissemination of a survey to the North American composition community. The end result, the Composer’s Guide to the Tuba, is a practical, accessible, and composer-centric guide to the modern capabilities of the tuba family of instruments. iv To Sara and Dad, who both kept me going with their never-ending love. -

'The Performing Pitch of William Byrd's Latin Liturgical Polyphony: a Guide

The Performing Pitch of William Byrd’s Latin Liturgical Polyphony: A Guide for Historically Minded Interpreters Andrew Johnstone REA: A Journal of Religion, Education and the Arts, Issue 10, 'Sacred Music', 2016 The choosing of a suitable performing pitch is a task that faces all interpreters of sixteenth- century vocal polyphony. As any choral director with the relevant experience will know, decisions about pitch are inseparable from decisions about programming, since some degree of transposition—be it effected on the printed page or by the mental agility of the singers—is almost invariably required to bring the conventions of Renaissance vocal scoring into alignment with the parameters of the more modern SATB ensemble. To be sure, the problem will always admit the purely pragmatic solution of adopting the pitch that best suits the available voices. Such a solution cannot of itself be to the detriment of a compelling, musicianly interpretation, and precedent for it may be cited in historic accounts of choosing a pitch according to the capabilities of the available bass voices (Ganassi 1542, chapter 11) and transposing polyphony so as to align the tenor part with the octave in which chorale melodies were customarily sung (Burmeister 1606, chapter 8). At the same time, transpositions oriented to the comfort zone of present-day choirs will almost certainly result in sonorities differing appreciably from those the composer had in mind. It is therefore to those interested in this aspect of the composer’s intentions, as well as to those curious about the why and the wherefore of Renaissance notation, that the following observations are offered. -

Healthy Performance Practice for Male Barbershop Singers

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Performance, and Creative Activity: Hixson-Lied College of Fine and Fine and Performing Arts, Hixson-Lied College Performing Arts of Spring 4-18-2011 Healthy Performance Practice for Male Barbershop Singers Jacob K. Bartlett University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/hixsonliedstudent Part of the Music Practice Commons, and the Other Music Commons Bartlett, Jacob K., "Healthy Performance Practice for Male Barbershop Singers" (2011). Student Research, Performance, and Creative Activity: Hixson-Lied College of Fine and Performing Arts. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/hixsonliedstudent/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Fine and Performing Arts, Hixson-Lied College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Performance, and Creative Activity: Hixson-Lied College of Fine and Performing Arts by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HEALTHY PERFORMANCE PRACTICE FOR MALE BARBERSHOP SINGERS by Jacob K. Bartlett A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor William Shomos Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2011 HEALTHY PERFORMANCE PRACTICE FOR MALE BARBERSHOP SINGERS Jacob K. Bartlett, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2011 Adviser: William Shomos Barbershop singing is a hobby enjoyed by hundreds of thousands of men and women across the world. We attend conventions, shows, competitions, and educational outreach programs each year at our own expense to preserve a style we truly love. -

The Harmonic Oscillator

Appendix A The Harmonic Oscillator Properties of the harmonic oscillator arise so often throughout this book that it seemed best to treat the mathematics involved in a separate Appendix. A.1 Simple Harmonic Oscillator The harmonic oscillator equation dates to the time of Newton and Hooke. It follows by combining Newton’s Law of motion (F = Ma, where F is the force on a mass M and a is its acceleration) and Hooke’s Law (which states that the restoring force from a compressed or extended spring is proportional to the displacement from equilibrium and in the opposite direction: thus, FSpring =−Kx, where K is the spring constant) (Fig. A.1). Taking x = 0 as the equilibrium position and letting the force from the spring act on the mass: d2x M + Kx = 0. (A.1) dt2 2 = Dividing by the mass and defining ω0 K/M, the equation becomes d2x + ω2x = 0. (A.2) dt2 0 As may be seen by direct substitution, this equation has simple solutions of the form x = x0 sin ω0t or x0 = cos ω0t, (A.3) The original version of this chapter was revised: Pages 329, 330, 335, and 347 were corrected. The correction to this chapter is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92796-1_8 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 329 W. R. Bennett, Jr., The Science of Musical Sound, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92796-1 330 A The Harmonic Oscillator Fig. A.1 Frictionless harmonic oscillator showing the spring in compressed and extended positions where t is the time and x0 is the maximum amplitude of the oscillation. -

The Female Broadway Belt Voice: the Singer’S Perspective

The Female Broadway Belt Voice: The Singer’s Perspective Christianne Roll INTRODUCTION he female music theater belt voice was heard on the musical comedy stage at the beginning of the twentieth century as a way for the unamplified female voice to be heard in its middle, more speech-like range.1 Thus, the belt sound emerged as female music Ttheater singers reworked their vocal approach in the range of C4 to C5. This “traditional” belt production, in the range of C4-C5, can be described as full, bright, brassy, speech-like, and loud.2 Traditional female belt, demonstrated Christianne Roll by singers like Ethel Merman and Patti LuPone, is typically a chest voice dominant production.3 In rock/pop inspired music theater productions since 2000, such as Hamilton (2015) and Waitress (2016), females are now required to sound like rock/pop singers and produce the belt sound to the top of the staff and beyond.4 This higher extension of the female music theater belt voice in the range of D5–F5, demonstrated by singers like Jessie Mueller and Eden Espinosa, is a significant change. Female music theater singers have had to adjust their vocal strategies to sing these higher belt notes. This high belt is typically produced by a more mix-belt approach, which can be a more chest (dominant)-mix or head (dominant)-mix.5 Whereas traditional belt is produced on open vowels such as /a/ and /æ/ with vibrato, high belt sound is narrow, produced with more closed vowels, such as /e/, and very little use of vibrato.6 With the relatively recent establishment and evolution of the belt sound, its pedagogy remains unsettled.7 However, singers continue to model the style on Broadway and in the music theater industry, and currently belting is the dominant style of singing required for females pursuing a professional career in music theater.8 To meet these industry demands, female singers need current, effective strategies to produce the belt sound.