33China Coal[1]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autonomous Exploration and Mapping of Abandoned Mines

Autonomous Exploration and Mapping of Abandoned Mines Sebastian Thrun2, Scott Thayer1, William Whittaker1, Christopher Baker1 Wolfram Burgard3, David Ferguson1, Dirk Hahnel¨ 3, Michael Montemerlo2, Aaron Morris1, Zachary Omohundro1, Charlie Reverte1, Warren Whittaker1 1 Robotics Institute, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 2 Computer Science Department, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 3 Computer Science Department, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany Abstract Abandoned mines pose significant threats to society, yet a large fraction of them lack ac- curate maps. This article discusses the software architecture of an autonomous robotic system designed to explore and map abandoned mines. We have built a robot capable of au- tonomously exploring abandoned mines. A new set of software tools is presented, enabling robots to acquire maps of unprecedented size and accuracy. On May 30, 2003, our robot “Groundhog” successfully explored and mapped a main corridor of the abandoned Mathies mine near Courtney, PA. The article also discusses some of the challenges that arise in the subterraneans environments, and some the difficulties of building truly autonomous robots. 1 Introduction In recent years, the quest to find and explore new, unexplored terrain has led to the deploy- ment of more and more sophisticated robotic systems, designed to traverse increasingly remote locations. Robotic systems have successfully explored volcanoes [5], searched meteorites in Antarctica [1, 44], traversed deserts [3], explored and mapped the sea bed [12], even explored other planets [26]. This article presents a robot system designed to explore spaces much closer to us: abandoned underground mines. According to a recent survey [6], “tens of thousands, perhaps even hundreds of thousands, of abandoned mines exist today in the United States. -

Annual Report Annual Report 2020

2020 Annual Report Annual Report 2020 For further details about information disclosure, please visit the website of Yanzhou Coal Mining Company Limited at Important Notice The Board, Supervisory Committee and the Directors, Supervisors and senior management of the Company warrant the authenticity, accuracy and completeness of the information contained in the annual report and there are no misrepresentations, misleading statements contained in or material omissions from the annual report for which they shall assume joint and several responsibilities. The 2020 Annual Report of Yanzhou Coal Mining Company Limited has been approved by the eleventh meeting of the eighth session of the Board. All ten Directors of quorum attended the meeting. SHINEWING (HK) CPA Limited issued the standard independent auditor report with clean opinion for the Company. Mr. Li Xiyong, Chairman of the Board, Mr. Zhao Qingchun, Chief Financial Officer, and Mr. Xu Jian, head of Finance Management Department, hereby warrant the authenticity, accuracy and completeness of the financial statements contained in this annual report. The Board of the Company proposed to distribute a cash dividend of RMB10.00 per ten shares (tax inclusive) for the year of 2020 based on the number of shares on the record date of the dividend and equity distribution. The forward-looking statements contained in this annual report regarding the Company’s future plans do not constitute any substantive commitment to investors and investors are reminded of the investment risks. There was no appropriation of funds of the Company by the Controlling Shareholder or its related parties for non-operational activities. There were no guarantees granted to external parties by the Company without complying with the prescribed decision-making procedures. -

Treatment of Disused Lead Mine Shafts

Cover: The many surviving lead mining shafts and sites of Derbyshire and the Peak District feature a wide variety of conservation interests. As shown here (top left - David Webb) shafts provide access for cave exploration, though a safe method of access may need to be provided as shown here (bottom right – Ian Gates). On the surface there is archaeological interest in the waste hillocks and other structure (top right John Humble) and specialist plant communities survive that include metal tolerant species such as this spring sandwort (bottom left – John Humble). Shafts were often lined with a dry stone walling known as ginging (centre right – David Webb) which can be vulnerable to damage when they are capped. Report prepared by Entec UK Ltd for Derbyshire County Council, Peak District National Park Authority, Natural England, English Heritage and Derbyshire Caving Association. Funded by the above organisations and East Midlands Development Agency Copyright @2007 Derbyshire County Council, Peak District National Park Authority, Natural England, English Heritage and Derbyshire Caving Association. Images @2007 Derbyshire County Council, Peak District National Park Authority, Natural England, English Heritage and Derbyshire Caving Association unless otherwise stated. First published 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or any information storage or retrieval system , without permission in writing from the copyright holders. Designed by Entec Ltd. I Foreword The lead mining remains of Derbyshire and the Peak District are of national importance for their ecological, archaeological, historical, geological and landscape value, as well as providing opportunities for recreation and enjoyment which are valued by many people. -

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

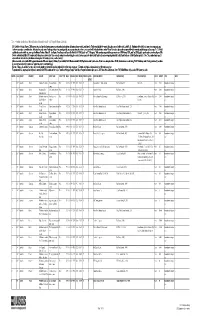

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

The Case for Mine Energy – Unlocking Deployment at Scale in the UK a Mine Energy White Paper

The Case for Mine Energy – unlocking deployment at scale in the UK A mine energy white paper @northeastlep northeastlep.co.uk @northeastlep northeastlep.co.uk Foreword At the heart of this Government’s agenda are three key priorities: the development of new and innovative sources of employment and economic growth, rapid decarbonisation of our society, and levelling up - reducing the inequalities between diferent parts of the UK. I’m therefore delighted to be able to ofer my support to this report, which, perhaps uniquely, involves an approach which has the potential to address all three of these priorities. Mine energy, the use of the geothermally heated water in abandoned coal mines, is not a new technology, but it is one with the potential to deliver thousands of jobs. One quarter of the UK’s homes and businesses are sited on former coalfields. The Coal Authority estimates that there is an estimated 2.2 GWh of heat available – enough to heat all of these homes and businesses, and drive economic growth in some of the most disadvantaged communities in our country. Indeed, this report demonstrates that if we only implement the 42 projects currently on the Coal Authority’s books, we will deliver almost 4,500 direct jobs and a further 9-11,000 in the supply chain, at the same time saving 90,000 tonnes of carbon. The report also identifies a number of issues which need to be addressed to take full advantage of this opportunity; with investment, intelligence, supply chain development, skills and technical support all needing attention. -

United Kingdom – Extensive Potential and a Positive Outlook by Paul Lusty, British Geological Survey Introduction in Relation

United Kingdom – extensive potential and a positive outlook By Paul Lusty, British Geological Survey Introduction In relation to its size the United Kingdom (UK) is remarkably well-endowed with mineral resources as a result of its complex geological history. Their extraction and use have played an important role in the development of the UK economy over many years and minerals are currently worked at some 2100 mine and quarry sites. Production is now largely confined to construction minerals, primarily aggregates, energy minerals and industrial minerals including salt, potash, kaolin and fluorspar, although renewed interest in metals is an important development in recent years. With surging global demand for minerals the UK is seen by explorers as an attractive location to develop projects. With low political risk and excellent infrastructure a survey conducted by Resources Stocks (2009) ranked the UK twelfth in a global assessment of countries’ risk profiles for resource sector investment. Northern Ireland is notable in terms of the extensive licence coverage for gold and base metal exploration and in having the UK’s only operational metalliferous mine. The most advanced projects elsewhere include the Hemerdon tin-tungsten deposit in Devon, the South Crofty tin deposit in Cornwall and the Cononish gold deposit in central Scotland. UK coal has seen a resurgence during the last three years driven largely by higher global prices, making it more competitive with imports. Coal is also viewed as having a key role in the future UK energy mix. This has led to greater investment in UK operations resulting in increased numbers of new opencast sites commencing production and more permit applications for further sites. -

Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone Land Use in Northern Nevada: a Class I Ethnographic/Ethnohistoric Overview

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management NEVADA NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Ginny Bengston CULTURAL RESOURCE SERIES NO. 12 2003 SWCA ENVIROHMENTAL CON..·S:.. .U LTt;NTS . iitew.a,e.El t:ti.r B'i!lt e.a:b ~f l-amd :Nf'arat:1.iern'.~nt N~:¥G~GI Sl$i~-'®'ffl'c~. P,rceP,GJ r.ei l l§y. SWGA.,,En:v,ir.e.m"me'Y-tfol I €on's.wlf.arats NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Submitted to BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Nevada State Office 1340 Financial Boulevard Reno, Nevada 89520-0008 Submitted by SWCA, INC. Environmental Consultants 5370 Kietzke Lane, Suite 205 Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 826-1700 Prepared by Ginny Bengston SWCA Cultural Resources Report No. 02-551 December 16, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................v List of Tables .................................................................v List of Appendixes ............................................................ vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................1 CHAPTER 2. ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW .....................................4 Northern Paiute ............................................................4 Habitation Patterns .......................................................8 Subsistence .............................................................9 Burial Practices ........................................................11 -

Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics 2012

Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics 2012 Production team: Iain MacLeay Kevin Harris Anwar Annut and chapter authors A National Statistics publication London: TSO © Crown Copyright 2012 All rights reserved First published 2012 ISBN 9780115155284 Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics Enquiries about statistics in this publication should be made to the contact named at the end of the relevant chapter. Brief extracts from this publication may be reproduced provided that the source is fully acknowledged. General enquiries about the publication, and proposals for reproduction of larger extracts, should be addressed to Kevin Harris, at the address given in paragraph XXIX of the Introduction. The Department of Energy and Climate Change reserves the right to revise or discontinue the text or any table contained in this Digest without prior notice. About TSO's Standing Order Service The Standing Order Service, open to all TSO account holders, allows customers to automatically receive the publications they require in a specified subject area, thereby saving them the time, trouble and expense of placing individual orders, also without handling charges normally incurred when placing ad-hoc orders. Customers may choose from over 4,000 classifications arranged in 250 sub groups under 30 major subject areas. These classifications enable customers to choose from a wide variety of subjects, those publications that are of special interest to them. This is a particularly valuable service for the specialist library or research body. All publications will be dispatched immediately after publication date. Write to TSO, Standing Order Department, PO Box 29, St Crispins, Duke Street, Norwich, NR3 1GN, quoting reference 12.01.013. -

Downloaded 09/29/21 03:16 AM UTC 2058 JOURNAL of HYDROMETEOROLOGY VOLUME 20

OCTOBER 2019 A N E T A L . 2057 Utilizing Precipitation and Spring Discharge Data to Identify Groundwater Quick Flow Belts in a Karst Spring Catchment LIXING AN Tianjin Key Laboratory of Wireless Mobile Communications and Power Transmission, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, China XINGYUAN REN National Marine Data and Information Service, Tianjin, China YONGHONG HAO Tianjin Key Laboratory of Water Resources and Environment, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, China TIAN-CHYI JIM YEH Tianjin Key Laboratory of Water Resources and Environment, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, China, and Department of Hydrology and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona BAOJU ZHANG Tianjin Key Laboratory of Wireless Mobile Communications and Power Transmission, Tianjin Normal University, Tianjin, China (Manuscript received 4 January 2019, in final form 30 April 2019) ABSTRACT In karst terrains, fractures and conduits often occur in clusters, forming groundwater quick flow belts, which are the major passages of groundwater and solute transport. We propose a cost-effective method that utilizes precipitation and spring discharge data to identify groundwater quick flow belts by the multitaper method (MTM). In this paper, hydrological processes were regarded as the transformation of precipitation signals to spring discharge signals in a karst spring catchment. During the processes, karst aquifers played the role of signal filters. Only those signals with high energy could penetrate through aquifers and reflect in the spring discharge, while other weak signals were filtered out or altered by aquifers. Hence, MTM was applied to detect and reconstruct the signals that penetrate through aquifers. Subsequently, by analyzing the reconstructed signals of precipitation with those of spring discharge, we acquired the hydraulic response time and identified the quick flow belts. -

Yanzhou Coal Mining Company Limited

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this circular or as to what action to take in relation to this circular, you should consult your licensed securities dealer, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional adviser. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in Yanzhou Coal Mining Company Limited, you should at once hand this circular to the purchaser(s) or transferee(s) or to the bank, or a licensed securities dealer or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser(s) or transferee(s). Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this circular, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this circular. This circular is for information only and does not constitute an invitation or offer to acquire, purchase or subscribe for any securities in the Company. 兗州煤業股份有限公司 YANZHOU COAL MINING COMPANY LIMITED (A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 1171) (1) PROPOSED APPOINTMENT OF NON-INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS AND INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS; (2) PROPOSED APPOINTMENT OF NON-STAFF REPRESENTATIVE SUPERVISORS; (3) PROPOSED RENEWAL OF LIABILITY INSURANCE FOR DIRECTORS, SUPERVISORS AND SENIOR -

ABM Investama Tbk PT Involvement in Coal Mining Adani Ports & Special

Company Comment ABM Investama Tbk PT Involvement in coal mining Adani Ports & Special Economic Zone Ltd Violation of established norms Adaro Energy Tbk PT Involvement in coal mining Adaro Indonesia PT Involvement in coal mining Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings Inc Involvement in nuclear weapons Aeroteh SA Involvement in cluster munitions Agritrade Resources Ltd Involvement in coal mining Airbus SE Involvement in nuclear weapons Alfa Energi Investama Tbk PT Involvement in coal mining Alliance Holdings GP LP Involvement in coal mining Alliance Resource Operating Partners LP / Alliance Involvement in coal mining Resource Finance Corp Alliance Resource Partners LP Involvement in coal mining Alpha Natural Resources Inc Involvement in coal mining Altius Minerals Corp Involvement in coal mining Ammunition & Metallurgy Industries Group Involvement in anti-personnel mines Anglo Pacific Group plc Involvement in coal mining Anhui Great Wall Military Industry Co Ltd Involvement in cluster munitions Arch Coal Inc Involvement in coal mining Armament Research and Development Involvement in cluster munitions & anti- Establishment personnel mines Arrow Exploration Corp Involvement in oil sand Aryt Industries Ltd Involvement in cluster munitions Ashakacem PLC Involvement in coal mining Asia Resource Minerals PLC Involvement in coal mining Athabasca Oil Corp Involvement in oil sand Atomenergoprom JSC (Atomic Energy Power Corp) Involvement in nuclear weapons Babcock International Group PLC Involvement in nuclear weapons BAE Systems PLC Involvement in nuclear weapons -

The Mineral Industry of China in 2016

2016 Minerals Yearbook CHINA [ADVANCE RELEASE] U.S. Department of the Interior December 2018 U.S. Geological Survey The Mineral Industry of China By Sean Xun In China, unprecedented economic growth since the late of the country’s total nonagricultural employment. In 2016, 20th century had resulted in large increases in the country’s the total investment in fixed assets (excluding that by rural production of and demand for mineral commodities. These households; see reference at the end of the paragraph for a changes were dominating factors in the development of the detailed definition) was $8.78 trillion, of which $2.72 trillion global mineral industry during the past two decades. In more was invested in the manufacturing sector and $149 billion was recent years, owing to the country’s economic slowdown invested in the mining sector (National Bureau of Statistics of and to stricter environmental regulations in place by the China, 2017b, sec. 3–1, 3–3, 3–6, 4–5, 10–6). Government since late 2012, the mineral industry in China had In 2016, the foreign direct investment (FDI) actually used faced some challenges, such as underutilization of production in China was $126 billion, which was the same as in 2015. capacity, slow demand growth, and low profitability. To In 2016, about 0.08% of the FDI was directed to the mining address these challenges, the Government had implemented sector compared with 0.2% in 2015, and 27% was directed to policies of capacity control (to restrict the addition of new the manufacturing sector compared with 31% in 2015.