Oup of Sanctimonious Provincials Who Put Their Own Well- Being Above That of the Commonwealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial America's Rejection of Free Grace Theology

COLONIAL AMERICA’S REJECTION OF FREE GRACE THEOLOGY L. E. BROWN Prescott, Arizona I. INTRODUCTION Many Free Grace adherents assume that grace theology, the de facto doctrine of the first century church, was lost until recently. Such is not the case. Michael Makidon has demonstrated, for example, that Free Grace views surfaced in Scotland in the 18th century Marrow Contro- versy.1 The “Marrow Men” were clear: faith is the sole condition of justi- fication, and assurance is the essence of justifying faith. Eighty years earlier peace was broken in the Massachusetts Bay Col- ony (MBC) over these doctrines. That upheaval, labeled the “Antinomian Controversy,” occupied the MBC for seventeen months from October 1636 to March 1638. The civil and ecclesiastical trials of Anne Hutchin- son (1591-1643), whose vocal opposition to the “covenant of works”2 gained unfavorable attention from the civil authorities, and served as a beard for theological adversaries John Cotton (1585-1652) and Thomas Shepard (1605-1649). This article will survey the three main interpretations intellectual his- torians offer for the Antinomian Controversy. The primary focus will be on the doctrine of assurance, with an emphasis on sixteenth-century Brit- ish Calvinism. We will evaluate the opposing views of John Cotton and Thomas Shepard. Finally, we will consider the opportunity that Free Grace theology missed in the Antinomian Controversy. 1 Michael Makidon, “The Marrow Controversy,” Journal of the Grace Evangelical Theological Society 16:31 (Autumn 2003), 65-77. See also Edward Fisher, The Marrow of Modern Divinity [book on-line] (No Pub: ND); available from http://www.mountzion.org/text/marrow/marrow.html; Internet; accessed August 6, 2007. -

The Legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Michael J. Puglisi College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Puglisi, Michael J., "The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623769. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-f5eh-p644 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. -

Title Page R.J. Pederson

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/22159 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Pederson, Randall James Title: Unity in diversity : English puritans and the puritan reformation, 1603-1689 Issue Date: 2013-11-07 Chapter 5 Tobias Crisp (1600-1642/3) 5.1 Introduction In this chapter, we will assess the “radical” Puritan Tobias Crisp, whose life and thought illustrates both unitas and diversitas within Puritanism.1 As a representative of the antinomian strain, his teachings and emphasis on non-introspective piety illuminate internal tendencies within Puritanism to come up with an alternative to the precisianist strain.2 Within the literature, Crisp has been called “an antecedent of the Ranters,” “the great champion of antinomianism,” the “arch-Antinomian” and “a stimulator of religious controversy.”3 In his own time, Crisp was accused of both “Antinomianisme” and “Libertinisme,” the latter title of which he fully embraced because, for Crisp, at the heart of the theological debate that characterized his ministry was one’s freedom (libertas fidelium) in Christ,4 and the attainment of assurance.5 Crisp remains one of the most 1 As we saw in Chapter 1, identifying a Puritan as either “orthodox” or “radical” is not always easy, nor are the terms always mutually exclusive. As with Rous, Crisp typifies elements of Reformed orthodoxy and more “radical” notions associated with antinomianism. 2 David Como, “Crisp, Tobias (1600-1643),” in Puritans and Puritanism in Europe and America: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia, ed. Francis J. Bremer and Tom Webster (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2006), 1:64; Victor L. -

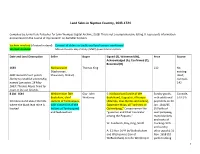

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Prepared by Grace, for Grace

Prepared by Grace, for Grace Prepared by Grace, for Grace The Puritans on God’s Ordinary Way of Leading Sinners to Christ Joel R. Beeke and Paul M. Smalley Reformation Heritage Books Grand Rapids, Michigan Prepared by Grace, for Grace © 2013 by Joel R. Beeke and Paul M. Smalley All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Direct your requests to the publisher at the following address: Reformation Heritage Books 2965 Leonard St. NE Grand Rapids, MI 49525 616-977-0889 / Fax 616-285-3246 [email protected] www.heritagebooks.org Printed in the United States of America 13 14 15 16 17 18/10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beeke, Joel R., 1952- Prepared by grace, for grace : the puritans on god's ordinary way of leading sinners to Christ / Joel R. Beeke and Paul M. Smalley. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60178-234-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Salvation—Puritans. 2. Grace (Theology) 3. Puritans—Doctrines. I. Smalley, Paul M. II. Title. BX9323.B439 2013 234—dc23 2013006563 For additional Reformed literature request a free book list from Reformation Heritage Books at the above regular or e-mail address. To Derek Thomas my faithful friend and fellow-laborer in Christ Thanks so much for all you are and have done for me, our seminary, and book ministry. -

Download Issue

PILGRIM HOPKINS HERITAGE SOCIETY ATLANTIC CROSSINGS ENGLAND ~ BERMUDA ~ JAMESTOWN ~ ENGLAND ~ PLYMOUTH Mayflower Sea Venture VOLUME 7, ISSUE 1 www.pilgrimhopkins.com JUNE 2013 From Plymouth to Pokonoket by Judith Brister and Susan Abanor n the spring of 1621, Pilgrims tion of a peace accord I Stephen Hopkins and Edward Wins- with Massasoit during his low were sent out on an official mission March 22, 1621 visit to by Governor Bradford which entailed a Plymouth. Known by the two-day trek from Plymouth to the Pok- Pilgrims as simply Mas- onoket village of the Great Sachem, or sasoit (which was really Massasoit, of the Wampanoag Confed- his title; he had other eracy. The village was likely located in names among his people, what is now Warren, Rhode Island, including Ousamequin), some 40-50 miles from Plymouth. this leader presided over The path from Plymouth to the site of the Pokanokets, the head- the Pokonoket village traverses the exist- ship tribe of the various ing towns of Carver, Middleboro, Taun- tribes that constituted the ton, Dighton, Somerset and Swansea, in Wampanoag nation. Massachusetts, and Barrington and War- When the Mayflower ren, Rhode Island. Today, except for a arrived, the Wampanoags small patch, the ancient Native American had been devastated by path has been covered by paved roads two recent outbreaks of that wind through these towns and outly- smallpox brought by pre- ing areas. In 1621, the region was un- Pilgrim Europeans, and known territory for the Pilgrims, whose despite misgivings and explorations until then had been limited some internal dissension, to Plymouth and Cape Cod. -

An Interview with Paul M. Smalley About His Co-Authored Book Prepared by Grace, for Grace: the Puritans on God’S Ordinary Way of Leading Sinners to Christ

An Interview with Paul M. Smalley about his co-authored book Prepared by Grace, for Grace: The Puritans on God’s Ordinary Way of Leading Sinners to Christ. Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2013, 297 pp., paperback. Interviewed by Brian G. Najapfour Brother, congratulations on your well-researched co-authored book with Dr. Joel Beeke. I am confident that Prepared by Grace, for Grace is destined to be a standard work on the subject. Thank you, Pastor Najapfour. We hope that by God’s grace the book will be useful. Here are some of my questions for you about your book: 1. Could you please briefly define the following terms as used in your book? I think defining these terms will help the readers of this interview better understand your discourse. a. Reformed, Puritan, & evangelical. Reformed refers to the stream of Christianity beginning with sixteenth-century Reformers such as Zwingli and Calvin, and defined by adherence to confessions such as the Heidelberg Catechism and the Westminster Standards. Puritanism was a movement of British Christians from the 1560s through about 1700 that emphasized applying the biblical doctrines rediscovered in the Reformation to one’s personal life, family, church, and nation. The Reformers (including Reformed and Lutheran Christians) called themselves “evangelicals” in the sixteenth century because God has restored to the church the biblical gospel (“evangel”) of salvation by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone according to Scripture alone for the glory of God alone. The term continues to be used today. b. Doctrine of preparation (Is this doctrine biblical? How is it different from the so- called preparationism?) The doctrine of preparation is the idea that God’s general way of bringing sinners to Christ is to awaken them to a sense of their spiritual need before they trust in Christ to save them. -

Americanancestors.Org Boston, MA 02116 — Michael F., Potomac, Md

Hire the Experts NEHGS Research Services Whether you are just beginning your family research or have been researching for many years, NEHGS Research Services is here to assist you. Hourly Research Our expert genealogists can assist you with general research requests, breaking down “brick walls,” retrieving manuscript materials, and obtaining probate records. In addition to working in the NEHGS library, we access microfilms and records from other repositories and gather information from around the world. Lineage Society Applications Our team of experienced researchers can research and prepare your lineage society application. We can determine qualifying ancestors, gather documentation for a single generation, or prepare the entire application from start to finish. Organization and Evaluation Our staff can help organize your materials, offer suggestions for further research, and assist in chart creation. areas of expertise Geographic United States • Canada • British Isles • Europe • Asia “Thank you so much — the material you sent provides exactly the connection Specialties for a second great grandmother who 16th–20th Century • Ethnic and Immigration • Military I was looking for. One by one, I’m Historical Perspective • Artifact Provenance • Lineage Verification • Native Cultures identifying the families of all the unidentified women in the family!” — Barbara R., Northampton, Mass. “Incredible work, and much deeper get started information than we were expecting . call 617-226-1233 mail NEHGS Research Services We are eagerly awaiting the second email [email protected] 99–101 Newbury Street installment!” website www.AmericanAncestors.org Boston, MA 02116 — Michael F., Potomac, Md. AMERICancestorsAN New England, New York, and Beyond Spring 2012 • Vol. 13, No. 2 UP FRONT A Special Announcement . -

Guide to the Frost and Hill Family Papers

GUIDE TO THE FROST AND HILL FAMILY PAPERS AT THE NEW ENGLAND HISTORIC GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY Abstract: Captain Charles Frost (1630-1697) and Major John Hill (1666-1713) were militia officers responsible for defending Kittery and Saco, Maine under the direction of Massachusetts authorities during King William’s War, 1689-1697. The collection contains military orders, commissions, and correspondence with scattered Frost, Hill and Pepperell family documents and business papers. Collection dates: 1675-1760. Volume: 47 items. Repository: R. Stanton Avery Special Collections Call Number: Mss 1055 Copyright ©2010 by New England Historic Genealogical Society. All rights reserved. Reproductions are not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. Frost and Hill Family Papers Mss 1055 FAMILY HISTORY NOTE Names in bold represent creators of documents in this collection. FROST FAMILY CHARLES2 FROST (Nicholas1) was born in 1632 at Tiverton, England, and he was killed by Indians on 4 July 1697. Charles, at age 44, married on 27 December 1675 to MARY BOLLES. Mary was born 4 January 1641 in York, Maine, and she died 11 November 1704 in Wells, Maine. As a young child, Charles accompanied his family from England to the plantation of Pascataqua River in Maine. His father, Nicholas Frost (1585-1663), acquired two hundred acres in Kittery (incorporated in 1647). Charles Frost was frequently chosen as a representative for Kittery to the general court in Massachusetts. In 1669, the militia of Maine was organized into six companies one of which was commanded by Charles Frost. Frost was one of six councilors appointed to act as judges of the courts. -

Abbott, Abraham, Ache, Acklin, Adams, Adamson, Addis

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 25 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 224 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 72.100 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

CHAMBERLAIN Family.Pdf

Cknti^erkinMsmatrnXeia Seriesjr 1^. Your President asks your patience while 3/4 To what C family belong Thomas, recovering rroru a snapped tendon in nqr 21, living with Thomas Kolbert, writing hand; it has slowed down every- i'-iarion Co., bastern I;ist.,fr2l, VA (VI Va) tning 1 undertake, eBpeciaiiy correspond (1850 census); and James, 19, living ence, with Samuel uooper, same county and district (ibid). V^hat was the relation A.C.O, ship between the C, Hoibert and Cooper families between 1820 and 1850? Piy gr- grandfather, Raymond C, in 1850 was living with John B. Hoibert in Taylor ^Ui:;Rli>S Co.,Va (Vv' Va). In 1870 and 1880 Iowa census, Scr.uyier Co.,1.0., Thomas C, ca This section is primarily intended to be 40, was living there; buried in Coates- a service to the members of the CAA; vilie, Schuyler Go. Cemetery,close to non-members may have queries published Gr-grandfather Raymond, Is he a at a cost of $?• for a maxiBium of six brother of Raymond or member of another lines; additional lines, $1. each. family? Thomas and his parents were bom in VA (1880 census). Queries will be accepted for publication and responses forwarded after members' ' 3/5 Seek data on Griffin C. C, born CAA fomis have been completed and t hen in VAj mar. Elizabeth Brooks 1 Jan. compared with CAA records; this has 1810 in VA (Richmond?). He was oldest become necessary as some misinformation child of JaiJies C. C^riffm C.; removed to would otherwise be passas along, did CAA •. -

The Continuity and Paradox of Puritan Theology and Pastoral Authority

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 1998 In the name of the father: The continuity and paradox of Puritan theology and pastoral authority Patricia J. Hill-Zeigler University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Hill-Zeigler, Patricia J., "In the name of the father: The continuity and paradox of Puritan theology and pastoral authority" (1998). Doctoral Dissertations. 2012. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2012 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.