Lost Village of Greasley A4 Cover.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nottinghamshire's Sustainable Community Strategy

Nottinghamshire’s Sustainable Community Strategy the nottinghamshire partnership all together better 2010-2020 Contents 1 Foreword 5 2 Introduction 7 3 Nottinghamshire - our vision for 2020 9 4 How we put this strategy together What is this document based on? 11 How this document links with other important documents 11 Our evidence base 12 5 Nottinghamshire - the timeline 13 6 Nottinghamshire today 15 7 Key background issues 17 8 Nottinghamshire’s economy - recession and recovery 19 9 Key strategic challenges 21 10 Our priorities for the future A greener Nottinghamshire 23 A place where Nottinghamshire’s children achieve their full potential 27 A safer Nottinghamshire 33 Health and well-being for all 37 A more prosperous Nottinghamshire 43 Making Nottinghamshire’s communities stronger 47 11 Borough/District community strategies 51 12 Next steps and contacts 57 Nottinghamshire’s Sustainable Community Strategy 2010-2020 l p.3 Appendices I The Nottinghamshire Partnership 59 II Underpinning principles 61 III Our evidence base 63 IV Consultation 65 V Nottinghamshire - the timeline 67 VI Borough/District chapters Ashfield 69 Bassetlaw 74 Broxtowe 79 Gedling 83 Mansfield 87 Newark and Sherwood 92 Rushcliffe 94 VII Case studies 99 VIII Other relevant strategies and action plans 105 IX Performance management - how will we know that we have achieved our targets? 107 X List of acronyms 109 XI Glossary of terms 111 XII Equality impact assessment 117 p.4 l Nottinghamshire’s Sustainable Community Strategy 2010-2020 1 l Foreword This document, the second community strategy for Nottinghamshire, outlines the key priorities for the county over the next ten years. -

Download Original Attachment

Owner Name Address Postcode Current Rv THE OWNER TREETOP WORKSHOP THE BOTTOM YARD HORSLEY LN/DERBY RD COXBENCH DERBY DE21 5BD 1950 THE OWNER YEW TREE INN YEW TREE HILL HOLLOWAY MATLOCK, DERBYSHIRE DE4 5AR 3000 THE OWNER THE OLD BAKEHOUSE THE COMMON CRICH MATLOCK, DERBYSHIRE DE4 5BH 4600 THE OWNER ROOM 3 SECOND FLOOR VICTORIA HOUSE THE COMMON, CRICH MATLOCK, DERBYSHIRE DE4 5BH 1150 THE OWNER ROOM 2 SECOND FLOOR VICTORIA HOUSE THE COMMON CRICH MATLOCK, DERBYSHIRE DE4 5BH 800 THE OWNER WORKSHOP SUN LANE CRICH MATLOCK, DERBYSHIRE DE4 5BR 2600 THE OWNER JOVIAL DUTCHMAN THE CROSS CRICH MATLOCK, DERBYSHIRE DE4 5DH 3500 THE OWNER SPRINGFIELDS LEA MAIN ROAD LEA MATLOCK, DERBYSHIRE DE4 5GJ 1275 SLEEKMEAD PROPERTY COMPANY LTD PRIMROSE COTTAGE POTTERS HILL WHEATCROFT MATLOCK DERBYSHIRE DE4 5PH 1400 SLEEKMEAD PROPERTY COMPANY LTD PLAISTOW HALL FARM POTTERS HILL WHEATCROFT MATLOCK DERBYSHIRE DE4 5PH 1400 THE OWNER R/O 47 OXFORD STREET RIPLEY DERBYSHIRE DE5 3AG 2950 MACNEEL & PARTNERS LTD 53 OXFORD STREET RIPLEY DERBYSHIRE DE5 3AH 19000 MACNEEL & PARTNERS LTD OVER 53-57 OXFORD STREET (2399) RIPLEY DERBYSHIRE DE5 3AH 5000 THE OWNER 43A OXFORD STREET RIPLEY DERBYSHIRE DE5 3AH 2475 THE OWNER OXFORD CHAMBERS 41 OXFORD STREET RIPLEY DERBYSHIRE DE5 3AH 2800 THE OWNER OVER 4B OXFORD STREET RIPLEY DERBYSHIRE DE5 3AL 710 THE OWNER 3 WELL STREET RIPLEY DERBYSHIRE DE5 3AR 4550 LOCKWOOD PROPERTIES LTD DE JA VU 23 NOTTINGHAM ROAD RIPLEY DERBYSHIRE DE5 3AS 19500 THE OWNER REAR OF 94 NOTTINGHAM ROAD RIPLEY DERBYSHIRE DE5 3AX 1975 THE OWNER UNIT G PROSPECT COURT 192 -

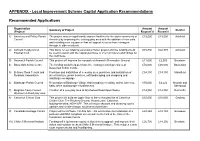

APPENDIX - Local Improvement Scheme Capital Application Recommendations

APPENDIX - Local Improvement Scheme Capital Application Recommendations Recommended Applications Organisation Amount Amount Summary of Project District (Project) Request’d Recom’d 1) Annesley and Felley Parish The project aims to significantly improve facilities for the wider community of £19,500 £19,500 Ashfield Council Annesley by improving the existing play area with the addition of new units and installing new equipment that will appeal to users from teenagers through to older residents. 2) Ashfield Rugby Union This bid is for our 'Making Larwood a Home' project and the funding would £45,830 £22,915 Ashfield Football Club be used to assist with the capital purchase of internal fixtures and fittings for the clubhouse. 3) Awsworth Parish Council This project will improve the car park at Awsworth Recreation Ground. £11,000 £2,000 Broxtowe 4) Bassetlaw Action Centre The funding would help purchase the existing (rented) premises at £50,000 £20,000 Bassetlaw Bassetlaw Action Centre. 5) Bellamy Road Tenant and Provision and installation of new play area, purchase and installation of £34,150 £34,150 Mansfield Resident Association street furniture, picnic benches, soft landscaping and designing and installing new signage 6) Bilsthorpe Parish Council Restoration of Bilsthorpe Village Hall including re-roofing, toilets, kitchens, £50,000 £2,222 Newark and halls, office and storage refurbishment. Sherwood 7) Bingham Town Council Creation of a new play area at Wychwood Road Open Space. £14,950 £14,950 Rushcliffe Wychwood Road play area 8) Calverton Cricket Club This project will build an upper floor to the cricket pavilion at Calverton £35,000 £10,000 Gedling Cricket Club, The Rookery Ground, Woods Lane, Calverton, Nottinghamshire, NG14 6FF. -

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

Nottinghamshire County Council Election of County Councillor for the Beeston Central and Rylands County Electoral Division NOTICE OF POLL Notice is hereby given that: 1. The following persons have been and stand validly nominated: SURNAME OTHER NAMES HOME ADDRESS DESCRIPTION (if NAMES OF THE PROPOSER (P), any) SECONDER (S) AND THE PERSONS WHO SIGNED THE NOMINATION PAPER Carr Barbara Caroline 5 Tracy Close, Beeston, Nottingham, Liberal Democrats Graham M Hopcroft(P), Audrey P NG9 3HW Hopcroft(S) Foale Kate 120 Cotgrave Lane, Tollerton, Labour Party Celia M Berry(P), Philip D Bust(S) Nottinghamshire, NG12 4FY McCann Duncan Stewart 15 Enfield Street, Beeston, Nottingham, The Conservative June L Dennis(P), James Philip Christian NG9 1DN Party Candidate Raynham-Gallivan(S) Venning Mary Evelyn 14 Bramcote Avenue, Beeston, Green Party Christina Y Roberts(P), Daniel P Nottingham, Nottinghamshire, NG9 4DG Roberts(S) 2. A POLL for the above election will be held on Thursday, 6th May 2021 between the hours of 07:00 and 22:00. 3. The number to be elected is ONE. The situation of the Polling Stations and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote at each station are set out below: PD Polling Station and Address Persons entitled to vote at that station BEC1 Oasis Church - Union Street Entrance, Willoughby Street, Beeston, Nottingham, NG9 2LT 1 to 1284 BEC2 Humber Lodge, Humber Road, Beeston, Nottingham, NG9 2DP 1 to 1687 BEC3 Templar Lodge, Beacon Road, Beeston, Nottingham, NG9 2JZ 1 to 1654 BER1 Beeston Rylands Community Centre, Leyton Crescent, -

Final Criteria Feb 2013

February 2013 Ashfield District Council Criteria for Local Heritage Asset Designation Contents Section 1: Preface Section 2: Introduction Section 3: Relevant Planning Policies 3.1 National Planning Policy Framework (2012) 3.5 Emerging Ashfield Local Plan Section 4: Local Heritage Assets 4.1 What is a Local Heritage Asset? 4.5 What is a Local Heritage Asset List? 4.8 How and when are Local Heritage Assets identified? 4.9 What does it mean if a building or structure is on the Local Heritage Asset List? Section 5: Local Historic Distinctiveness 5.1 The Colliery Industry 5.2 The Textile Industry 5.3 The Medieval Landscape 5.4 Vernacular Architectural Traditions Section 6: Criteria for identifying a Local Heritage Asset ELEMENTS OF INTEREST 6.4 Historic interest 6.5 Archaeological interest 6.6 Architectural interest 6.7 Artistic interest ELEMENTS OF SIGNIFICANCE 6.8 Measuring significance: Rarity 6.9 Measuring significance: Representativeness 6.10 Measuring significance: Aesthetic Appeal 6.11 Measuring significance: Integrity 6.12 Measuring significance: Association Section 7: Types of Local Heritage Assets 7.1 Building and Structures 7.2 Archaeological Sites 7.3 Landscapes and Landscape Features 7.4 Local Character Areas Section 8: How to nominate a site for inclusion on the Local Heritage Asset List Section 9: Consultation Section 10: Sources of further information Ashfield District Council Local Heritage Asset Nomination Form SECTION 1 1. Preface 1.1 Our local heritage and historic environment is an asset of enormous cultural, social, economic and environmental value, providing a valuable contribution to our sense of history, place and quality of life. -

9780521650601 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 0521650607 - Pragmatic Utopias: Ideals and Communities, 1200-1630 Edited by Rosemary Horrox and Sarah Rees Jones Index More information Index Aberdeen, Baxter,Richard, Abingdon,Edmund of,archbp of Canterbury, Bayly,Thomas, , Beauchamp,Richard,earl of Warwick, – Acthorp,Margaret of, Beaufort,Henry,bp of Winchester, adultery, –, Beaufort,Margaret,countess of Richmond, Aelred, , , , , , Aix en Provence, Beauvale Priory, Alexander III,pope, , Beckwith,William, Alexander IV,pope, Bedford,duke of, see John,duke of Bedford Alexander V,pope, beggars, –, , Allen,Robert, , Bell,John,bp of Worcester, All Souls College,Oxford, Belsham,John, , almshouses, , , , –, , –, Benedictines, , , , , –, , , , , , –, , – Americas, , Bereford,William, , anchoresses, , – Bergersh,Maud, Ancrene Riwle, Bernard,Richard, –, Ancrene Wisse, –, Bernwood Forest, Anglesey Priory, Besan¸con, Antwerp, , Beverley,Yorks, , , , apostasy, , , – Bicardike,John, appropriations, –, , , , Bildeston,Suff, , –, , Arthington,Henry, Bingham,William, – Asceles,Simon de, Black Death, , attorneys, – Blackwoode,Robert, – Augustinians, , , , , , Bohemia, Aumale,William of,earl of Yorkshire, Bonde,Thomas, , , –, Austria, , , , Boniface VIII,pope, Avignon, Botreaux,Margaret, –, , Aylmer,John,bp of London, Bradwardine,Thomas, Aymon,P`eire, , , , –, Brandesby,John, Bray,Reynold, Bainbridge,Christopher,archbp of York, Brinton,Thomas,bp of Rochester, Bristol, Balliol College,Oxford, , , , , , Brokley,John, Broomhall -

Field House Nursery

FIELD HOUSE NURSERY LEAKE ROAD, GOTHAM, NOTTINGHAMSHIRE NG11 0JN, U.K. Val Woolley & Bob Taylor SPECIALIST GROWERS of AURICULAS, PRIMULAS and ASTRANTIAS NATIONAL COLLECTION® HOLDERS FIELD HOUSE NURSERY Tel: 0115 9830 278 Mob: 07504 125 209 Email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Open by appointment only, 10am to 2.30pm, April 1st to June 30th and occasionally at other times by special arrangement. Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday HOW TO FIND US Field House Nursery is situated near to the M1 (East Midlands Airport exit Junction 24) and is within easy reach of most of the Midlands. We are only two hours drive from London. If you are coming from a distance it is best to telephone us first. AURICULAS Our world-famous collection of over 750 named auriculas is on display at the nursery. The plants are set out in groups - Alpines, Selfs, Edged, Borders and Doubles. We hold a NATIONAL COLLECTION of Show and Alpine Auriculas which may be viewed by appointment. PRIMULAS We grow many species of Asiatic and European primula, along with hundreds of cultivars and hybrids. AURICULA and PRIMULA Descriptive reference catalogue with 8-page coloured booklet of auricula pictures. 4 x First Class stamps please. Auricula and Primula Availability list 2 x First Class Stamps please – a new list will be issued in March 2016. SEED We sell seed of Primula and auricula, most of which we produce ourselves. List 2 x 1st Class Stamps. ASTRANTIAS. We hold a NATIONAL COLLECTION which may be viewed by appointment. We also have an excellent selection for sale at the nursery and by mail order. -

Amber Valley Bed Vacancies

Page 1 of 6 Amber Valley Care Home Homes for Older Adults Bed Vacancy List The care home vacancies information is taken from the NHS Care Homes Capacity Tracker, which is updated by the care homes themselves, and the provision of this information does not constitute any form of recommendation or decision by DCC. The identification of current vacancies is for information only to enable the client or their representative to make their own decision and choice. The information on bed vacancies is correct on the date checked but can change at any time. Please take steps to assure yourself of their current performance when considering using these care homes. Care Homes with Nursing (Registered for Nursing and Residential Care) Ashfields 34 Mansfield Road, Heanor, DE75 7AQ 01773 712664 Date checked – 21 September 21 Vacancies for general nursing and general Residential Bankwood Duffield Bank, Belper, DE56 4BG 01332 841373 Date Checked – 21 September 21 Vacancies for general nursing and general residential The Firs 90 Glasshouse Hill, Codnor, DE5 9QT 01773 743810 Option 3 Date Checked – 21 September 21 Vacancies for general nursing and general residential PUBLIC Page 2 of 6 Hollybank House Chesterfield Road, Oakerthorpe, Alfreton, DE55 7PL 01773 831791 Date Checked – 21 September 21 Vacancies for general nursing Killburn Care Home Dale Park Avenue, Kilburn, DE56 0NR 01332 880644 Date Checked – 21 September 21 Not accepting new clients just now Maple Leaf House Kirk Close, Ripley, DE5 3RY 01773 513361 Date Checked – 21 September 21 Vacancies for -

It's Pantomime Season! Colourful Hands Cherish Me

The IRISMagazine Autumn 2019 IT’S PANTOMIME SEASON! COLOURFUL HANDS CHERISH ME For Parents Of Children And Young People With Special Educational Needs And Disabilities in Nottingham and Nottinghamshire CONTENTS 2 Rumbletums 3 Autumn Recipes 3 Cherish Me 4 It’s Pantomime Season RUMBLETUMS Rumbletums, in Kimberley, is a community hub Colourful Hands with a café and supported training project. The 4 group began eight years ago as an idea between parents of children with learning disabilities and 5 Support and Advice additional needs. They noticed that there was a for the New School lack of opportunities for their children and others like them to develop the skills and experience Year needed to succeed in life and decided to do something about. YOUNG PEOPLE’S ZONE The café opened in 2011, with a fully voluntary staff base and has grown organically over time. Fundraising and 6 - 11 Events generous donations from local people and businesses has meant that the project has been able to grow organically and now employs a number of full-time staff, who work 12 Independent alongside the volunteers and trainees. Living: Travel and Transport The café provides an opportunity for 16-30 year olds with learning disabilities and additional needs, such as physical Nottingham disabilities, to work in a café environment. With a variety of roles to fill, trainees could be working in the kitchen or front of house, depending on their comfort levels, abilities 13 Beauty and preferences. Shifts last a maximum of three hours. Instagrammers with Disabilities Trainees benefit from a wide range of experiences and skills outside the café too. -

AMBER VALLEY VACANT INDUSTRIAL PREMISES SCHEDULE Address Town Specification Tenure Size, Sqft

AMBER VALLEY VACANT INDUSTRIAL PREMISES SCHEDULE Address Town Specification Tenure Size, sqft The Depot, Codnor Gate Ripley Good Leasehold 43,274 Industrial Estate Salcombe Road, Meadow Alfreton Moderate Freehold/Leasehold 37,364 Lane Industrial Estate, Alfreton Unit 1 Azalea Close, Clover Somercotes Good Leasehold 25,788 Nook Industrial Estate Unit A Azalea Close, Clover Somercotes Moderate Leasehold/Freehold 25,218 Nook Industrial Estate Block 19, Amber Business Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 25,200 Centre, Riddings Block 2 Unit 2, Amber Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 25,091 Business Centre, Riddings Unit 3 Wimsey Way, Alfreton Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 20,424 Trading Estate Block 24 Unit 3, Amber Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 18,734 Business Centre, Riddings Derby Road Marehay Moderate Freehold 17,500 Block 24 Unit 2, Amber Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 15,568 Business Centre, Riddings Unit 2A Wimsey Way, Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 15,543 Alfreton Trading Estate Block 20, Amber Business Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 14,833 Centre, Riddings Unit 2 Wimsey Way, Alfreton Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 14,543 Trading Estate Block 21, Amber Business Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 14,368 Centre, Riddings Three Industrial Units, Heage Ripley Good Leasehold 13,700 Road Industrial Estate Industrial premises with Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 13,110 offices, Nix’s Hill, Hockley Way Unit 2 Azalea Close, Clover Somercotes Good Leasehold 13,006 Nook Industrial Estate Derby Road Industrial Estate Heanor Moderate Leasehold 11,458 Block 23 Unit 2, Amber Alfreton Moderate -

Newsletter 150 August 2011

protecting and improving the environment Newsletter 150 August 2011 Inside: The local Heritage Open Days programme, the Society 2011- 2012 Speakers programme and our first Membership Survey EDITORIAL “.. Beeston .. was always a sort of eyesore to us .. a wilderness of more or less squalid or vulgar little houses and mean shops .. a tolerably quiet sort of place and you rode or drove through it in a very few minutes.” These are the words of Catherine Mary Bearne written in the “Charlton Chronicles” circa 1860. How do you think the current Beeston (and district) compares and how do you think the Society is doing in meeting our objective of “ protecting and improving the environment ” ? In the centre pages of this issue is a survey intended as an opportunity for you to express your views about the work of the Society. Please do take the time to complete it and hand your response to a member of the Committee. A summary will appear in the December edition of the newsletter. Also enclosed with this edition is the local programme of Heritage Open Days and the 2011 – 2012 programme of Speakers. We try to distribute this information far and wide as both series of events have a great deal to offer but as always we appreciate the support of you as a member. So please do make notes in your diaries to attend, and also tell all your friends and neighbours ! DL - - - - - - - - - - - - COMMITTEE NEWS Your Committee meets monthly and various members will report on current topics as a “watching brief”. Among the items being monitored and discussed are; The three Wind Turbines currently being proposed by the University of Nottingham. -

East Midlands

Liberal Democrat submission for BCE 3rd consultation East Midlands Submission to the Boundary Commission for England third period of consultation: East Midlands Summary There is a factual error in the Commission’s report concerning the Liberal Democrat counter-proposals in the Leicestershire / Northamptonshire / Nottinghamshire / Rutland sub-region. We would, therefore, ask the Commission to reconsider the scheme we put forward. We welcome the change the Commission has made to its proposal for Mansfield. We welcome the fact that the Commission has kept to its original proposals in Lincolnshire, much of Derbyshire and Derby, and in Northampton. We consider that the changes that the Commission has made to four constituencies in Derbyshire, affecting the disposition of three wards, are finely balanced judgement calls with which we are content to accept the Commission’s view. The change that the Commission has made to the Kettering and Wellingborough constituencies would not have needed to be considered if it had agreed to our proposal for an unchanged Wellingborough seat. The Commission’s proposal to move the Burton Joyce and Stoke Bardolph ward into its proposed Sherwood constituency means that it is now proposing three Nottinghamshire constituencies (Bassetlaw, Broxtowe, Sherwood) which contain a ward which is inaccessible from the rest of the seat. We are not in agreement with the Commission’s failure to comply with the spirit of the legislation or the letter of its own guidelines in respect of these three proposed constituencies. We are not in agreement with the Commission’s failure to respect the boundaries of the City of Nottingham to the extent of proposing three constituencies that cross the Unitary Authority boundary.