Human Rights Education & Black Liberation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding African Armies

REPORT Nº 27 — April 2016 Understanding African armies RAPPORTEURS David Chuter Florence Gaub WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM Taynja Abdel Baghy, Aline Leboeuf, José Luengo-Cabrera, Jérôme Spinoza Reports European Union Institute for Security Studies EU Institute for Security Studies 100, avenue de Suffren 75015 Paris http://www.iss.europa.eu Director: Antonio Missiroli © EU Institute for Security Studies, 2016. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. Print ISBN 978-92-9198-482-4 ISSN 1830-9747 doi:10.2815/97283 QN-AF-16-003-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9198-483-1 ISSN 2363-264X doi:10.2815/088701 QN-AF-16-003-EN-N Published by the EU Institute for Security Studies and printed in France by Jouve. Graphic design by Metropolis, Lisbon. Maps: Léonie Schlosser; António Dias (Metropolis). Cover photograph: Kenyan army soldier Nicholas Munyanya. Credit: Ben Curtis/AP/SIPA CONTENTS Foreword 5 Antonio Missiroli I. Introduction: history and origins 9 II. The business of war: capacities and conflicts 15 III. The business of politics: coups and people 25 IV. Current and future challenges 37 V. Food for thought 41 Annexes 45 Tables 46 List of references 65 Abbreviations 69 Notes on the contributors 71 ISSReportNo.27 List of maps Figure 1: Peace missions in Africa 8 Figure 2: Independence of African States 11 Figure 3: Overview of countries and their armed forces 14 Figure 4: A history of external influences in Africa 17 Figure 5: Armed conflicts involving African armies 20 Figure 6: Global peace index 22 Figure -

President's Report

· mount holyoke · PRESIDENT’S REPORT · a note from the · PRESIDENT The College has always been a place where big visions take shape. For over 180 years, we have opened opportunities for students to deepen their understanding and sharpen their response to a fast-changing world with challenges both known and unknown. We prepare students to learn and to lead because in life and work, we know this is what makes all the difference. Now that we have been deeply engaged in the work for two years of our five-year Plan for 2021, I’m delighted to share our progress, including an overview of some of Mount Holyoke’s new strategic initia- tives. In January 2018, we opened the Dining Commons, a part of the new Community Center, which is now also nearing completion. With the extensive renovations to Blanchard Hall we are creating a co-curricular hub in support of student leadership and programs, as well as a coffee shop and pub. We’ve also added new residential, co-curricular, and academic spaces. These spaces are the heart of our community-building efforts, giving more attention to shared endeavors and creating a sense of belonging. They represent a commitment to place at Mount Holyoke, reminding us all of the power of relationships that is in the very warp and woof of the College and the Alumnae Association. There is an energy and excitement to our being in the same space at the same times each day to eat, talk, think, and debate in companionship and cooperation. I hope the stories in these pages excite you about our current initi atives and our plans for the future. -

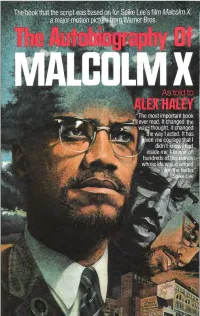

The-Autobiography-Of-Malcolm-X.Pdf

The absorbing personal story of the most dynamic leader of the Black Revolution. It is a testament of great emotional power from which every American can learn much. But, above all, this book shows the Malcolm X that very few people knew, the man behind the stereotyped image of the hate-preacher-a sensitive, proud, highly intelligent man whose plan to move into the mainstream of the Black Revolution was cut short by a hail of assassins' bullets, a man who felt certain "he would not live long enough to see this book appear. "In the agony of [his] self-creation [is] the agony of an entire.people in their search for identity. No man has better expressed his people's trapped anguish." -The New York Review of Books Books published by The Ballantine Publishing Group are available at quantity discounts on bulk purchases for premium, educational, fund-raising, and special sales use. For details, please call 1-800-733-3000. THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OFMALCOLMX With the assistance ofAlex Haley Foreword by Attallah Shabazz Introduction by M. S. Handler Epilogue by Alex Haley Afterword by Ossie Davis BALLANTINE BOOKS• NEW YORK Sale of this book without a front cover may be unauthorized. If this book is coverless, it may have been reported to the publisher as "unsold or destroyed" and neither the author nor the publisher may have received payment for it. A Ballantine Book Published by The Ballantine Publishing Group Copyright© 1964 by Alex Haley and Malcolm X Copyright© 1965 by Alex Haley and Betty Shabazz Introduction copyright© 1965 by M. -

African Studies Association 59Th Annual Meeting

AFRICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION 59TH ANNUAL MEETING IMAGINING AFRICA AT THE CENTER: BRIDGING SCHOLARSHIP, POLICY, AND REPRESENTATION IN AFRICAN STUDIES December 1 - 3, 2016 Marriott Wardman Park Hotel, Washington, D.C. PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Benjamin N. Lawrance, Rochester Institute of Technology William G. Moseley, Macalester College LOCAL ARRANGEMENTS COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Eve Ferguson, Library of Congress Alem Hailu, Howard University Carl LeVan, American University 1 ASA OFFICERS President: Dorothy Hodgson, Rutgers University Vice President: Anne Pitcher, University of Michigan Past President: Toyin Falola, University of Texas-Austin Treasurer: Kathleen Sheldon, University of California, Los Angeles BOARD OF DIRECTORS Aderonke Adesola Adesanya, James Madison University Ousseina Alidou, Rutgers University Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Columbia University Brenda Chalfin, University of Florida Mary Jane Deeb, Library of Congress Peter Lewis, Johns Hopkins University Peter Little, Emory University Timothy Longman, Boston University Jennifer Yanco, Boston University ASA SECRETARIAT Suzanne Baazet, Executive Director Kathryn Salucka, Program Manager Renée DeLancey, Program Manager Mark Fiala, Financial Manager Sonja Madison, Executive Assistant EDITORS OF ASA PUBLICATIONS African Studies Review: Elliot Fratkin, Smith College Sean Redding, Amherst College John Lemly, Mount Holyoke College Richard Waller, Bucknell University Kenneth Harrow, Michigan State University Cajetan Iheka, University of Alabama History in Africa: Jan Jansen, Institute of Cultural -

The Anglophone Cameroon Crisis: by Jon Lunn and Louisa Brooke-Holland April 2019 Update

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8331, 17 April 2019 The Anglophone Cameroon crisis: By Jon Lunn and Louisa April 2019 update Brooke-Holland Contents: 1. Overview 2. History and its legacies 3. 2015-17: main developments 4. 2018: main developments 5. Events during 2019 and future prospects 6. Response of Western governments and the UN www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The Anglophone Cameroon crisis: April 2019 update Contents Summary 3 1. History and its legacies 5 2. 2015-17: main developments 8 3. 2018: main developments 10 4. Events during 2019 and future prospects 12 5. Response of Western governments and the UN 13 Cover page image copyright: Image 5584098178_709d889580_o – Welcome signs to Santa, gateway to the anglophone Northwest Region, Cameroon, March 2011 by Joel Abroad – Flickr.com page. Licensed by Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)/ image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 17 April 2019 Summary Relations between the two Anglophone regions of Cameroon and the country’s dominant Francophone elite have long been fraught. Over the past three years, tensions have escalated seriously and since October 2017 violent conflict has erupted between armed separatist groups and the security forces, with both sides being accused of committing human rights abuses. The tensions originate in a complex and contested decolonisation process in the late-1950s and early-1960s, in which Britain, as one of the colonial powers, was heavily involved. Federal arrangements were scrapped in 1972 by a Francophone- dominated central government. Many English-speaking Cameroonians have long complained that they are politically, economically and linguistically marginalised. -

The BG News February 20, 2001

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-20-2001 The BG News February 20, 2001 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 20, 2001" (2001). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6766. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6766 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. State University TUESDAY February 20, 2001 BASKETBALL: CLOUDY Men's Basketball faces HIGH43ILOW34 top ranked Kent today at www.binews.com 8 p.m.; PAGE 10 independent student press VOLUME 90 ISSUE 101 Student groups'budgets probed ByCrarfUford ed among 60-70 organizations. The SOFB had proposed to put money for transportation, where CHIEF REPORTER Last year the total amount of caps on things such as how another organization doesn't," CAMPUS ORGANIZATIONS REQUEST FUNDS Every year at this time, each of money that was applied for was much an organization could he said. "One group may need University campus organizations make their requests to the Student the University's campus organi- $400,000. This year it is $350,000. receive toward T-shirts or other more money for conferences Organization Funding board for their programs. zations make their pitch to the In an attempt to curb the promotional items. -

Jessica Krug , Fugitive Modernities: Kisama and the Politics of Freedom (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 280 Pp, Paperback, ISBN 9781478001546

All the contents of this journal, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License Jessica Krug , Fugitive Modernities: Kisama and the Politics of Freedom (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 280 pp, paperback, ISBN 9781478001546. This is a book about the political imaginations and intellectual labor of fugi- tives. It is about people who didn’t write, by choice. — Jessica Krug, Fugitive Modernities I am no scholar of Angola. I am not particularly knowledgeable about Portuguese colonialism; I have learnt the trans-Atlantic slave trade, yes, but no more than other informed readers disturbed by its ongoing afterlives. It is therefore telling that I came across Jessica Krug’s Fugitive Modernities in a conversation with friends similarly unacquainted with West Central Africa and the Americas, but, like me, animated by questions that lie at the heart of this book: How do we write about the disap- peared? How to put into words communities whose worlds have been targeted in acts of mass violence? How do we narrate the worlds of those who actively tried to evade the power that, as Trouillot reminds us, makes and records history? My friends and I focus on post-20th century communities elsewhere upended by other forms of violence, including settler-colonial destruction in Palestine, the Ottoman geno- cide of Armenians, and imperial war in the Afghanistan-Pakistan border regions.1 In contrast, Fugitive Modernities engages the ideas of communities escaping the grip of brutal states and the violence of the trans-Atlantic slave trade around present-day Angola, Colombia and Brazil from the 16th century until today. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Country Travel Risk Summaries

COUNTRY RISK SUMMARIES Powered by FocusPoint International, Inc. Report for Week Ending September 19, 2021 Latest Updates: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, India, Israel, Mali, Mexico, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen. ▪ Afghanistan: On September 14, thousands held a protest in Kandahar during afternoon hours local time to denounce a Taliban decision to evict residents in Firqa area. No further details were immediately available. ▪ Burkina Faso: On September 13, at least four people were killed and several others ijured after suspected Islamist militants ambushed a gendarme patrol escorting mining workers between Sakoani and Matiacoali in Est Region. Several gendarmes were missing following the attack. ▪ Cameroon: On September 14, at least seven soldiers were killed in clashes with separatist fighters in kikaikelaki, Northwest region. Another two soldiers were killed in an ambush in Chounghi on September 11. ▪ India: On September 16, at least six people were killed, including one each in Kendrapara and Subarnapur districts, and around 20,522 others evacuated, while 7,500 houses were damaged across Odisha state over the last three days, due to floods triggered by heavy rainfall. Disaster teams were sent to Balasore, Bhadrak and Kendrapara districts. Further floods were expected along the Mahanadi River and its tributaries. ▪ Israel: On September 13, at least two people were injured after being stabbed near Jerusalem Central Bus Station during afternoon hours local time. No further details were immediately available, but the assailant was shot dead by security forces. ▪ Mali: On September 13, at least five government soldiers and three Islamist militants were killed in clashes near Manidje in Kolongo commune, Macina cercle, Segou region, during morning hours local time. -

Report: the State of Black Gw Presented by the Black Student Union Fall 2020

REPORT: THE STATE OF BLACK GW PRESENTED BY THE BLACK STUDENT UNION FALL 2020 Email: [email protected] Instagram: @gwubsu Facebook: @GWBSU This report is presented to administrators, faculty, and student leaders at The George Washington University on behalf of the Black community by the Black Student Union. CONTENTS I. CURRENT BLACK ORGANIZATIONS 2 II. EXECUTIVE STATEMENT 3 III. INTRODUCTION 5 IV. HISTORY OF BLACK GW 6 V. COMMUNITY ACHIEVEMENTS 2020 7 A. MEDIA ATTENTION 8 VI. FINANCIAL SUPPORT 9 VII. FALL 2020 SURVEY DATA 11 VIII. ANALYSIS OF SURVEY RESULTS 14 IX. RECOMMENDATIONS 16 X. CONTRIBUTORS 20 XI. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 21 1 CURRENT BLACK ORGANIZATIONS The Black Student Union African Student Association Ethiopian-Eritrean Student Association ALIANZA Black Men's Initiative Black Women's Forum GW National Council of Negro Women GW NAACP GW Black Defiance Queer and Trans People of Color Association Xola Black Girl Mentorship Black Graduate Student Association The Multicultural Business Student Association GW National Society of Black Engineers GW National Association of Black Journalists Young Black Professionals in International Affairs The African Development Initiative Undergraduate Chapter of the Black Law Student Association D.R.E.A.M.S GW National Pan-Hellenic Council Gamma Alpha Phi Chapter of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity Inc. Nu Beta Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Inc. Kappa Chi Chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity Inc. Mu Beta Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. Mu Delta Chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha Xi Sigma Chapter of Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc. The Williams “Black” House The Black Ace Magazine GW Ubuntu 2 EXECUTIVE STATEMENT It is no secret that Black students at The George Washington University do not have an equitable student experience to our peers. -

Blacklivesmatter—Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2021 #BlackLivesMatter—Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change Jamillah Bowman Williams Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Naomi Mezey Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Lisa O. Singh Georgetown University, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2387 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3860435 California Law Review Online, Vol. 12, Reckoning and Reformation symposium. This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Law and Society Commons #BlackLivesMatter— Getting from Contemporary Social Movements to Structural Change Jamillah Bowman Williams*, Naomi Mezey**, and Lisa Singh*** Introduction ................................................................................................. 2 I. Methodology ............................................................................................ 5 II. BLM: From Contemporary Social Movement to Structural Change ..... 6 A. Black Lives Matter as a Social Media Powerhouse ................. 6 B. Tweets and Streets: The Dynamic Relationship between Online and Offline Activism ................................................. 12 C. A Theory of How to Move from Social Media -

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020 1 7 Anti-Racist Books Recommended by Educators and Activists from the New York Magazine https://nymag.com/strategist/article/anti-racist-reading- list.html?utm_source=insta&utm_medium=s1&utm_campaign=strategist By The Editors of NY Magazine With protests across the country calling for systemic change and justice for the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade, many people are asking themselves what they can do to help. Joining protests and making donations to organizations like Know Your Rights Camp, the ACLU, or the National Bail Fund Network are good steps, but many anti-racist educators and activists say that to truly be anti-racist, we have to commit ourselves to the ongoing fight against racism — in the world and in us. To help you get started, we’ve compiled the following list of books suggested by anti-racist organizations, educators, and black- owned bookstores (which we recommend visiting online to purchase these books). They cover the history of racism in America, identifying white privilege, and looking at the intersection of racism and misogyny. We’ve also collected a list of recommended books to help parents raise anti-racist children here. Hard Conversations: Intro to Racism - Patti Digh's Strong Offer This is a month-long online seminar program hosted by authors, speakers, and social justice activists Patti Digh and Victor Lee Lewis, who was featured in the documentary film, The Color of Fear, with help from a community of people who want and are willing to help us understand the reality of racism by telling their stories and sharing their resources.