Leopards of the Magical Dawn Science and the Cosmological Foundations of Igbo Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Idol to Art: African 'Objects with Power': a Challenge for Missionaries, Anthropologists and Museum Curators

From idol to art African ‘objects with power’: a challenge for missionaries, anthropologists and museum curators African Studies Centre African Studies Collection, vol. 59 From idol to art African ‘objects with power’: a challenge for missionaries, anthropologists and museum curators Harrie Leyten Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands [email protected] http://www.ascleiden.nl Cover design: Heike Slingerland Cover photos: Left: An Ikenga of the Igbo, Nigeria. Courtesy of the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford Middle: Asuman, probably of the Ashanti, Fanti and Sefwi, Ghana. Courtesy of the Afrika Museum, Berg en Dal Right: Nkisi mabiala ma ndembe of the Yombe, Congo. Courtesy of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Author has made all reasonable efforts to trace all rights holders to any copyrighted ma- terial used in this work. In cases where these efforts have not been successful the pub- lisher welcomes communications from copyright holders, so that the appropriate acknowledgements can be made in future editions, and to settle other permission mat- ters. Maps: Nel de Vink (DeVink Mapdesign) Printed by Ipskamp Drukkers, Enschede ISSN: 1876-018x ISBN: 978-94-6173-720-5 © Harrie M. Leyten, 2015 For Clémence Contents Glossary vi Foreword xv 1. FROM IDOL TO ART:INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Two Epa masks in a missionary museum: A case study 1 1.2 From Idol to Art: Research question 11 1.3 Theoretical framework 15 1.4 Objects with power 29 1.5 Plan and structure of this book 35 2. IKENGA,MINKISI AND ASUMAN 40 2.1 Ikenga 40 2.2 Minkisi 49 2.3 Asuman 65 3. -

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: the Igbo Experience

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: The Igbo Experience A thesis submitted to the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS), Universität Bayreuth, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Dr. Phil.) in English Linguistics By Uchenna Oyali Supervisor: PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe Mentor: Prof. Dr. Susanne Mühleisen Mentor: Prof. Dr. Eva Spies September 2018 i Dedication To Mma Ụsọ m Okwufie nwa eze… who made the journey easier and gave me the best gift ever and Dikeọgụ Egbe a na-agba anyanwụ who fought against every odd to stay with me and always gives me those smiles that make life more beautiful i Acknowledgements Otu onye adịghị azụ nwa. So say my Igbo people. One person does not raise a child. The same goes for this study. I owe its success to many beautiful hearts I met before and during the period of my studies. I was able to embark on and complete this project because of them. Whatever shortcomings in the study, though, remain mine. I appreciate my uncle and lecturer, Chief Pius Enebeli Opene, who put in my head the idea of joining the academia. Though he did not live to see me complete this program, I want him to know that his son completed the program successfully, and that his encouraging words still guide and motivate me as I strive for greater heights. Words fail me to adequately express my gratitude to my supervisor, PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe. His encouragements and confidence in me made me believe in myself again, for I was at the verge of giving up. -

208, (Issn: 2276-8645) 197 S

International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Reviews Vol.8 No.1, April 2018; p.197 – 208, (ISSN: 2276-8645) SUPERNATURALISM IN AFRICAN LITERATURE A STUDY OF LAYE’S THE AFRICAN CHILD AND AMADI’S THE CONCUBINE CHINYERE OJIAKOR (Ph.D) Department of English Madonna University Nigeria [email protected] & NKECHI EZENWAMADU (Ph.D) Department of English Madonna University Nigeria [email protected] Abstract This article x-rays the existence of the supernatural and their influence on mankind which has become a pre-dominant factor that has gained prominence and importance from time immemorial, and how writers have tried to project this concept in their literary engagements. In an attempt to establish this argument, the researcher explored Elechi Amadi's The Concubine and Camara Laye's The African Child. These novels depict and explore the idea of the supernatural in various manifestations and they are rich in supernatural and are rooted in the mythology and traditional African belief of supernaturalism. Supernaturalism is the belief that there are beings, forces, and phenomena such as God, angels or miracles which interact with the physical universe in remarkable and unique ways. The African man had begun to have some conceptions about the spiritual or mysterious essence of some natural phenomena and had begun to interpret his life in tandem with the "unknown". Opponents of these beliefs seem to pose the question: are there forces beyond the natural forces studied by physics and ways of sensing that go beyond our biological senses and instruments? They recognized that there may always be things outside the realm of human understanding as of yet unconfirmed which the African, not been able to research deeply on it, would term "supernatural". -

History of Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Igboland (1923 – 2010 )

NJOKU, MOSES CHIDI PG/Ph.D/09/51692 A HISTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN IGBOLAND (1923 – 2010 ) FACULTY OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION Digitally Signed by : Content manager’s Name Fred Attah DN : CN = Webmaster’s name O= University of Nigeri a, Nsukka OU = Innovation Centre 1 A HISTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN IGBOLAND (1923 – 2010) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION AND CULTURAL STUDIES, FACULTY OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) DEGREE IN RELIGION BY NJOKU, MOSES CHIDI PG/Ph.D/09/51692 SUPERVISOR: REV. FR. PROF. H. C. ACHUNIKE 2014 Approval Page 2 This thesis has been approved for the Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka By --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Rev. Fr. Prof. H. C. Achunike Date Supervisor -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ External Examiner Date Prof Musa Gaiya --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Internal Examiner Date Prof C.O.T. Ugwu -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Internal Examiner Date Prof Agha U. Agha -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Head of Department Date Rev. Fr. Prof H.C. Achunike --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Dean of Faculty Date Prof I.A. Madu Certification 3 We certify that this thesis -

Cultural Impacts of Tourism: the Ac Se of the “Dogon Country” in Mali Mamadou Ballo

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 2010 Cultural impacts of tourism: The ac se of the “Dogon Country” in Mali Mamadou Ballo Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Ballo, Mamadou, "Cultural impacts of tourism: The case of the “Dogon Country” in Mali" (2010). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CULTURAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM: The case of the “Dogon Country” in Mali A Thesis presented to the faculty in the College of Applied Science and Technology School of Hospitality and Service Management at Rochester Institute of Technology By Mamadou Ballo Thesis Supervisor Richard Rick Lagiewski Date approved:______/_______/_______ February 2010 VâÄàâÜtÄ \ÅÑtvàá Éy gÉâÜ|áÅM vtáx Éy WÉzÉÇá |Ç `tÄ| TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Abstract…………………………………………………..……….………………………………7 Introduction…………………………………………………………..……………………………9 1.1. Background: overview of tourism in Mali…………………….….…..………………………9 1.2. Purpose of the study…………………………………………………...………….…………13 1.3. Significance of the study………………………..……………………...……………………13 1.4. Definition of key terms…………………………………………………...…………………14 CHAPTER 2 Literature Review…………………………………….……….………….………………………15 CHAPTER 3 Methodology……………………………….……………………………………………………28 3.1. Description of the sample………………………...…………………………………………29 3.2. Language…………….…………………………...………………………….………………30 3.3. Scope and limitations……………………...……………………………...…………………30 3.4. Weakness of the study………………………..…………………………….………………30 3.5. Research questions …………………………………..……………………..………………30 CHAPTER 4 Results analysis…………………………………………………………………………………..31 CHAPTER 5 Conclusions and Recommendations …………….………………………………………………56 5.1. Major findings …………………………...….………………………………………………56 5.2. -

Saharan Africa: the Igbo Paradigm

Journal of International Education and Leadership Volume 5 Issue 1 Spring 2015 http://www.jielusa.org/ ISSN: 2161-7252 The Re-Birth of African Moral Traditions as Key to the Development of Sub- Saharan Africa: The Igbo Paradigm Chika J. B. Gabriel Okpalike Nnamdi Azikiwe University This work is set against the backdrop of the Sub-Saharan African environment observed to be morally degenerative. It judges that the level of decadence in the continent that could even amount to depravity could be blamed upon the disconnect between the present-day African and a moral tradition that has been swept under the carpet through history; this tradition being grounded upon a world view. World-view lies at the basis of the interpretation and operation of the world. It is the foundation of culture, religion, philosophy, morality and so forth; an attempt of humans to impose an order in which the human society works.1 Most times when the African world-view is discussed, the Africa often thought of and represented is the Africa as before in which it is very likely to see religion and community feature as two basic characters of Africa from which morality can be sifted. In his popular work Things Fall Apart, Chinua Achebe had above all things shown that this old Africa has been replaced by a new breed and things cannot be the same again. In the first instance, the former African communalism in which the community was the primary beneficiary of individual wealth has been wrestled down by capitalism in which the individual is defined by the extent in which he accumulates surplus value. -

Encoded Language As Powerful Tool. Insights from Okǝti Ụmụakpo-Lejja Ọmaba Chant

Journal of Language and Cultural Education, 2020, 8(3) ISSN 1339-4584 DOI: 10.2478/jolace-2020-0025 Traditional Segregation: Encoded Language as Powerful Tool. Insights from Okǝti Ụmụakpo-Lejja Ọmaba chant Uchechukwu E. Madu Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Nigeria [email protected] Abstract Language becomes a tool for power and segregation when it functions as a social divider among individuals. Language creates a division between the educated and uneducated, an indigene and non-indigene of a place; an initiate and uninitiated member of a sect. Focusing on the opposition between expressions and their meanings, this study examines Ụmụakpo- Lejja Okǝti Ọmaba chant, which is a heroic and masculine performance that takes place in the Okǝti (masking enclosure of the deity) of Umuakpo village square in Lejja town of Enugu State, Nigeria. The mystified language promotes discrimination among initiates, non- initiates, and women. Ọmaba is a popular fertility Deity among the Nsukka-Igbo extraction and Egara Ọmaba (Ọmaba chant) generally applies to the various chants performed to honour the deity during its periodical stay on earth. Using Schleiermacher’s Literary Hermeneutics Approach of the methodical practice of interpretation, the metaphorical language of the performance is interpreted to reveal the thoughts and the ideology behind the performance in totality. Among the Findings is that the textual language of Ụmụakpo- Lejja Okǝti Ọmaba chant is almost impossible without authorial and member’s interpretation and therefore, they are capable of initiating discriminatory perception of a non-initiate as a weakling or a woman. Keywords: Ọmaba chant, Ụmụakpo-Lejja, language, power, hermeneutics Introduction Beyond the primary function of language, which is the expression and communication of one’s ideas, a language is also a tool for power, segregation, and division in society. -

Purple Hibiscus

1 A GLOSSARY OF IGBO WORDS, NAMES AND PHRASES Taken from the text: Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Appendix A: Catholic Terms Appendix B: Pidgin English Compiled & Translated for the NW School by: Eze Anamelechi March 2009 A Abuja: Capital of Nigeria—Federal capital territory modeled after Washington, D.C. (p. 132) “Abumonye n'uwa, onyekambu n'uwa”: “Am I who in the world, who am I in this life?”‖ (p. 276) Adamu: Arabic/Islamic name for Adam, and thus very popular among Muslim Hausas of northern Nigeria. (p. 103) Ade Coker: Ade (ah-DEH) Yoruba male name meaning "crown" or "royal one." Lagosians are known to adopt foreign names (i.e. Coker) Agbogho: short for Agboghobia meaning young lady, maiden (p. 64) Agwonatumbe: "The snake that strikes the tortoise" (i.e. despite the shell/shield)—the name of a masquerade at Aro festival (p. 86) Aja: "sand" or the ritual of "appeasing an oracle" (p. 143) Akamu: Pap made from corn; like English custard made from corn starch; a common and standard accompaniment to Nigerian breakfasts (p. 41) Akara: Bean cake/Pea fritters made from fried ground black-eyed pea paste. A staple Nigerian veggie burger (p. 148) Aku na efe: Aku is flying (p. 218) Aku: Aku are winged termites most common during the rainy season when they swarm; also means "wealth." Akwam ozu: Funeral/grief ritual or send-off ceremonies for the dead. (p. 203) Amaka (f): Short form of female name Chiamaka meaning "God is beautiful" (p. 78) Amaka ka?: "Amaka say?" or guess? (p. -

Cth 821 Course Title: African Traditional Religious Mythology and Cosmology

NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COURSE CODE: CTH 821 COURSE TITLE: AFRICAN TRADITIONAL RELIGIOUS MYTHOLOGY AND COSMOLOGY 1 Course Code: CTH 821 Course Title: African Traditional Religious Mythology and Cosmology Course Developer: Rev. Fr. Dr. Michael .N. Ushe Department of Christian Theology School of Arts and Social Sciences National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos Course Writer: Rev. Fr. Dr. Michael .N. Ushe Department of Christian Theology School of Arts and Social Sciences National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos Programme Leader: Rev. Fr. Dr. Michael .N. Ushe Department of Christian Theology School of Arts and Social Sciences National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos Course Title: CTH 821 AFRICAN TRADITIONAL RELIGIOUS MYTHOLOGY AND COSMOLOGY COURSE DEVELOPER/WRITER: Rev. Fr. Dr. Ushe .N. Michael 2 National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos COURSE MODERATOR: Rev. Fr. Dr. Mike Okoronkwo National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos PROGRAMME LEADER: Rev. Fr. Dr. Ushe .N. Michael National Open University of Nigeria, Lagos CONTENTS PAGE Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………… …...i What you will learn in this course…………………………………………………………….…i-ii 3 Course Aims………………………………………………………..……………………………..ii Course objectives……………………………………………………………………………...iii-iii Working Through this course…………………………………………………………………….iii Course materials…………………………………………………………………………..……iv-v Study Units………………………………………………………………………………………..v Set Textbooks…………………………………………………………………………………….vi Assignment File…………………………………………………………………………………..vi -

A Socio- Economic History of Alcohol in Southeastern Nigeria Since 1890

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Background to the Study Alcohol has various socio-economic and cultural functions among the people of southeastern Nigeria. It is used in rituals, marriages, oath taking, festivals and entertainment. It is presented as a mark of respect and dignity. The basic alcoholic beverage produced and consumed in the area was palm -wine tapped from the oil palm tree or from the raffia- palm. Korieh notes that, from the fifteenth century contacts between the Europeans and peoples of eastern Nigeria especially during the Atlantic slave trade era, brought new varieties of alcoholic beverages primarily, gin and whisky.1 Thus, beginning from this period, gins especially schnapps from Holland became integrated in local culture of the peoples of Eastern Nigeria and even assumed ritual position.2 From the 1880s, alcohol became accepted as a medium of exchange for goods and services and a store of wealth.3 By the early twentieth century, alcohol played a major role in the Nigerian economy as one third of Nigeria‘s income was derived from import duties on liquor.4 Nevertheless, prior to the contact of the people of Southern Nigeria with the Europeans, alcohol was derived mainly from the oil palm and raffia palm trees which were numerous in the area. These palms were tapped and the sap collected and drunk at various occasions. From the era of the Trans- Atlantic slave trade, the import of gin, rum and whisky became prevalent.These were used in ex-change for slaves and to pay comey – a type of gratification to the chiefs. Even with the rise of legitimate trade in the 19th century alcoholic beverages of various sorts continued to play important roles in international trade.5 Centuries of importation of gin into the area led to the entrenchment of imported gin in the culture of the people. -

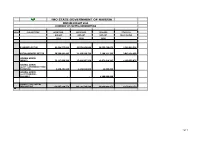

Imo State Government of Nigeria Revised Budget 2020 Summary of Capital Expenditure

IMO STATE GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA REVISED BUDGET 2020 SUMMARY OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE HEAD SUB-SECTORS APPROVED APPROVED REVISED COVID-19 BUDGET BUDGET BUDGET RESPONSIVE 2019 2020 2020 ECONOMIC SECTOR 82,439,555,839 63,576,043,808 20,555,468,871 2,186,094,528 SOCIAL SERVICES SECTOR 50,399,991,403 21,139,598,734 7,190,211,793 3,043,134,650 GENERAL ADMIN: (MDA'S) 72,117,999,396 17,421,907,270 12,971,619,207 1,150,599,075 GENERAL ADMIN: (GOVT COUNTERPART FUND PAYMENTS) 9,690,401,940 4,146,034,868 48,800,000 - GENERAL ADMIN: (GOVT TRANSFER - ISOPADEC) - - 4,200,000,000 - GRAND TOTAL CAPITAL EXPENDITURE 214,647,948,578 106,283,584,680 44,966,099,871 6,379,828,253 1of 1 IMO STATE GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA IMO STATE GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA REVISED BUDGET 2020 MINISTERIAL SUMMARY OF CAPITAL EXPENDITURE ECONOMIC SECTOR APPROVED 2019 APPROVED 2020 REVISED 2020 COVID-19 RESPONSIVE O414 MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND FOOD SECURITY 1,499,486,000 2,939,000,000 1,150,450,000 - 0 AGRIC & FOOD SECURITY 1,499,486,000 0414-2 MINISTRY OF LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT 1,147,000,000 367,000,000 367,000,000 - 0 LIVESTOCK 1,147,000,000 697000000 1147000000 0414-1 MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES 13,951,093,273 1,746,000,000 620,000,000 - 0 MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT 13951093273 450000000 O415 MINISTRY OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY 7,070,700,000 2,650,625,077 1,063,000,000 - -5,541,800,000 MINISTRY OF COMMERCE, INDUSTRY AND ENTREPRENEURSHIP1528900000 0419-2 MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES 2,880,754,957 2,657,000,000 636,869,000 - 1,261,745,492 MINISTRY OF PUBLIC UTILITIES 4,142,500,449 -

The Abolition of the Slave Trade in Southeastern Nigeria, 1885–1950

THE ABOLITION OF THE SLAVE TRADE IN SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1885–1950 Toyin Falola, Senior Editor The Frances Higginbotham Nalle Centennial Professor in History University of Texas at Austin (ISSN: 1092–5228) A complete list of titles in the Rochester Studies in African History and the Diaspora, in order of publication, may be found at the end of this book. THE ABOLITION OF THE SLAVE TRADE IN SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1885–1950 A. E. Afigbo UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER PRESS Copyright © 2006 A. E. Afigbo All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded, or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First published 2006 University of Rochester Press 668 Mt. Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA www.urpress.com and Boydell & Brewer Limited PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK www.boydellandbrewer.com ISBN: 1–58046–242–1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Afigbo, A. E. (Adiele Eberechukwu) The abolition of the slave trade in southeastern Nigeria, 1885-1950 / A.E. Afigbo. p. cm. – (Rochester studies in African history and the diaspora, ISSN 1092-5228 ; v. 25) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58046-242-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Slavery–Nigeria–History. 2. Slave trade–Nigeria–History. 3. Great Britain–Colonies–Africa–Administration I. Title. HT1394.N6A45 2006 306.3Ј6209669–dc22 2006023536 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. This publication is printed on acid-free paper.