A Creative Calling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title

Karaoke Box London www.karaokebox.co.uk 020 7329 9991 Song Title Artist 22 Taylor Swift 1234 Feist 1901 Birdy 1959 Lee Kernaghan 1973 James Blunt 1973 James Blunt 1983 Neon Trees 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince If U Got It Chris Malinchak Strong One Direction XO Beyonce (Baby Ive Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Cant Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Everybody's Gotta Learn Sometime) I Need Your Loving Baby D (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Wont You Play) Another Somebody… B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The World England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina And The Diamonds (I Love You) For Sentinmental Reasons Nat King Cole (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (Ill Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley and Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Reflections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Keep Feeling) Fascination The Human League (Maries The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Meet) The Flintstones B-52S (Mucho Mambo) Sway Shaft (Now and Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Sittin On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (The Man Who Shot) Liberty Valance Gene Pitney (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We Want) The Same Thing Belinda Carlisle (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1 2 3 4 (Sumpin New) Coolio 1 Thing Amerie 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Miles Away Hoodoo Gurus -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

50S 60S 70S.Txt 10Cc - I'm NOT in LOVE 10Cc - the THINGS WE DO for LOVE

50s 60s 70s.txt 10cc - I'M NOT IN LOVE 10cc - THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE A TASTE OF HONEY - OOGIE OOGIE OOGIE ABBA - DANCING QUEEN ABBA - FERNANDO ABBA - I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO ABBA - KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU ABBA - MAMMA MIA ABBA - SOS ABBA - TAKE A CHANCE ON ME ABBA - THE NAME OF THE GAME ABBA - WATERLOU AC/DC - HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC - YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG ACE - HOW LONG ADRESSI BROTHERS - WE'VE GOT TO GET IT ON AGAIN AEROSMITH - BACK IN THE SADDLE AEROSMITH - COME TOGETHER AEROSMITH - DREAM ON AEROSMITH - LAST CHILD AEROSMITH - SWEET EMOTION AEROSMITH - WALK THIS WAY ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - DAMNED IF I DO ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - DOCTOR TAR AND PROFESSOR FETHER ALAN PARSONS PROJECT - I WOULDNT WANT TO BE LIKE YOU ALBERT, MORRIS - FEELINGS ALIVE N KICKIN - TIGHTER TIGHTER ALLMAN BROTHERS - JESSICA ALLMAN BROTHERS - MELISSA ALLMAN BROTHERS - MIDNIGHT RIDER ALLMAN BROTHERS - RAMBLIN MAN ALLMAN BROTHERS - REVIVAL ALLMAN BROTHERS - SOUTHBOUND ALLMAN BROTHERS - WHIPPING POST ALLMAN, GREG - MIDNIGHT RIDER ALPERT, HERB - RISE AMAZING RHYTHM ACES - THIRD RATE ROMANCE AMBROSIA - BIGGEST PART OF ME AMBROSIA - HOLDING ON TO YESTERDAY AMBROSIA - HOW MUCH I FEEL AMBROSIA - YOU'RE THE ONLY WOMAN AMERICA - DAISY JANE AMERICA - HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA - I NEED YOU AMERICA - LONELY PEOPLE AMERICA - SISTER GOLDEN HAIR AMERICA - TIN MAN Page 1 50s 60s 70s.txt AMERICA - VENTURA HIGHWAY ANDERSON, LYNN - ROSE GARDEN ANDREA TRUE CONNECTION - MORE MORE MORE ANKA, PAUL - HAVING MY BABY APOLLO 100 - JOY ARGENT - HOLD YOUR HEAD UP ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - DO IT OR DIE ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - IMAGINARY LOVER ATLANTA RHYTHM SECTION - SO IN TO YOU AVALON, FRANKIE - VENUS AVERAGE WHITE BD - CUT THE CAKE AVERAGE WHITE BD - PICK UP THE PIECES B.T. -

The Other Side V O L U M E X X I V

N 0 V E M n E R 2 , I 9 9 4 The Other Side V o L u M E X X I V . I s !i u E 2 Po ectio Fall 1994 .I on 187 Unplugged Oh \veil, \vhatevp; Clip 'n' collect! NICOLE LAMPHERE EXPLORES THE EcocENTER (PG. 8) • PHoro EssAY OF THE O NTARIO YoUTH CENTER (PG. 13) • J uSTIN Roon ON MURALs (PG. 6) THE OTHER SIDE on everywhere, and that the apathetic are just too busy watching TV to figure this oul I am thinking particularly of the forum on Lab?r editor's desk organizing that took place in the Founder's Room on ~to~r 26th_m which representatives from a variety of Southern Cahforn1a orgamz "It was the sad confession, and continual exemplification, of the short-comings of the composite man- the spirit ingcoalitionsspokeon the work they havedone to secure basic rights burthened in clay and working in matter- and of the despair that assails the higher nature, at finding itself so miserably for documented and undocumented workers. There is also a flurry thwarted by the earthly part." -Nathania! Hawthorne, ''The Birth-mark" of activity that Pitzer faculty and students a_re participati_ng such as labor organizing internships and the on-gomg efforts w1th staff on Editors-in-Chief: Kim Gilmore On lazy afternoons in grade school,as the heaters purred softly in the background, the kids in my class laid comfortably campus to elevate working conditions for '1ow-level employees" Heidi Schumnn on the floor, mesmerized during story time by the tale of Harriet Tubman. -

Yamaha – Pianosoft Solo 29

YAMAHA – PIANOSOFT SOLO 29 SOLO COLLECTIONS ARTIST SERIES JOHN ARPIN – SARA DAVIS “A TIME FOR LOVE” BUECHNER – MY PHILIP AABERG – 1. A Time for Love 2. My Foolish FAVORITE ENCORES “MONTANA HALF LIGHT” Heart 3. As Time Goes By 4.The 1. Jesu, Joy Of Man’s Desiring 1. Going to the Sun 2. Montana Half Light 3. Slow Dance More I See You 5. Georgia On 2. “Bach Goes to Town” 4.Theme for Naomi 5. Marias River Breakdown 6.The Big My Mind 6. Embraceable You 3. Chanson 4. Golliwog’s Cake Open 7. Madame Sosthene from Belizaire the Cajun 8. 7. Sophisticated Lady 8. I Got It Walk 5. Contradance Diva 9. Before Barbed Wire 10. Upright 11. The Gift Bad and That Ain’t Good 9. 6. La Fille Aux Cheveux De Lin 12. Out of the Frame 13. Swoop Make Believe 10.An Affair to Remember (Our Love Affair) 7. A Giddy Girl 8. La Danse Des Demoiselles 00501169 .................................................................................$34.95 11. Somewhere Along the Way 12. All the Things You Are 9. Serenade Op. 29 10. Melodie Op. 8 No. 3 11. Let’s Call 13.Watch What Happens 14. Unchained Melody the Whole Thing Off A STEVE ALLEN 00501194 .................................................................................$34.95 00501230 .................................................................................$34.95 INTERLUDE 1. The Song Is You 2. These DAVID BENOIT – “SEATTLE MORNING” SARA DAVIS Foolish Things (Remind Me of 1. Waiting for Spring 2. Kei’s Song 3. Strange Meadowlard BUECHNER PLAYS You) 3. Lover Man (Oh Where 4. Linus and Lucy 5. Waltz for Debbie 6. Blue Rondo a la BRAHMS Can You Be) 4. -

2016 for 2016

A To Z: 2,016 For 2016 1 A BARENAKED LADIES 2 A PUNK VAMPIRE WEEKEND 3 A TEAM, THE ED SHEERAN 4 ABC JACKSON 5 5 ABOUT A GIRL (Unplugged) NIRVANA 6 ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE COUNTING CROWS 7 ACCIDENTS WILL HAPPEN ELVIS COSTELLO BRUCE HORNSBY & THE 8 ACROSS THE RIVER RANGE 9 ACROSS THE UNIVERSE BEATLES 10 ADDICTED TO LOVE ROBERT PALMER 11 ADIA SARAH McLACHLAN 12 ADVENTURE OF A LIFETIME COLDPLAY ADVENTURES OF RAIN DANCE 13 RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS MAGGIE, THE 14 AFTER MIDNIGHT J.J. CALE 15 AFTER MIDNIGHT ('88) ERIC CLAPTON 16 AGAIN LENNY KRAVITZ 17 AGAIN TONIGHT JOHN MELLENCAMP 18 AIN'T EVEN DONE WITH THE NIGHT JOHN MELLENCAMP 19 AIN'T NO REST FOR THE WICKED CAGE THE ELEPHANT 20 AIN'T NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERS 21 AIN'T TOO PROUD TO BEG ROLLING STONES 22 AIR THAT I BREATHE, THE HOLLIES 23 AJA STEELY DAN 24 ALABAMA GETAWAY GRATEFUL DEAD 25 ALISON ELVIS COSTELLO 26 ALIVE PEARL JAM 27 ALIVE AND KICKING SIMPLE MINDS 28 ALL ALONG THE WATCHTOWER BOB DYLAN 29 ALL ALONG THE WATCHTOWER JIMI HENDRIX 30 ALL APOLOGIES (UNPLUGGED) NIRVANA 31 ALL DOWN THE LINE ROLLING STONES 32 ALL FOR YOU SISTER HAZEL 33 ALL I WANNA DO SHERYL CROW 34 ALL I WANT TOAD THE WET SPROCKET 35 ALL I WANT IS YOU U2 36 ALL MIXED UP CARS 37 ALL MY LOVE LED ZEPPELIN 38 ALL MY LOVING BEATLES 39 ALL OVER YOU LIVE 40 ALL SHE WANTS TO DO IS DANCE DON HENLEY 41 ALL STAR SMASH MOUTH 42 ALL THE PRETTY GIRLS KALEO 43 ALL THESE THINGS THAT I'VE DONE THE KILLERS 44 ALL THIS TIME STING 45 ALL YOU NEED IS LOVE BEATLES 46 ALLISON ROAD GIN BLOSSOMS 47 ALONE SUSAN TEDESCHI 48 ALREADY GONE EAGLES 49 ALTHEA -

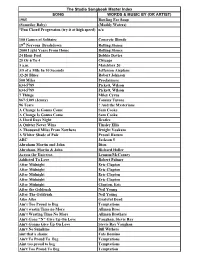

Copy of Songbook Master Index for Website

The Studio Songbook Master Index SONG WORDS & MUSIC BY (OR ARTIST) 1985 Bowling For Soup (Someday Baby) (Muddy Waters) *Fun Chord Progression (try it at high speed) n/a 100 Games of Solitaire Concrete Blonde 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones 2000 Light Years From Home Rolling Stones 24 Hour Fool Debbie Davies 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 3 a.m. Matchbox 20 3/5 of a Mile In 10 Seconds Jefferson Airplane 32-20 Blues Robert Johnson 500 Miles Proclaimers 634-5789 Pickett, Wilson 634-5789 Pickett, Wilson 7 Things Miley Cyrus 867-5309 (Jenny) Tommy Tutone 96 Tears ? And the Mysterians A Change Is Gonna Come Sam Cooke A Change Is Gonna Come Sam Cooke A Hard Days Night Beatles A Quitter Never Wins Tinsley Ellis A Thousand Miles From Nowhere Dwight Yoakam A Whiter Shade of Pale Procul Harum ABC Jackson 5 Abraham Martin and John Dion Abraham, Martin & John Richard Holler Across the Universe. Lennon/McCarney Addicted To Love Robert Palmer After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Clapton, Eric After the Goldrush Neil Young After The Goldrush Neil Young Aiko Aiko Grateful Dead Ain’t Too Proud to Beg Temptations Ain’t wastin Time no More Allman Bros Ain’t Wasting Time No More Allman Brothers Ain't Gone "N" Give Up On Love Vaughan, Stevie Ray Ain't Gonna Give Up On Love Stevie Ray Vaughan Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers aint that a shame Fats Domino Ain't To Proud To Beg Temptations Aint too proud to beg Temptations Ain't Too Proud To Beg Temptation Ain't Too Proud to Beg -

Camphill Correspondence July/August 2006

July/August 2006 CAMPHILL CORRESPONDENCE Diamond Head, bowl by Jenny Mendes, 2000 May you listen to your longing to be free. May the frames of your belonging be large enough for the dreams of your soul. May you arise each day with a voice of blessing whispering in your heart that something good is going to happen to you. May you find harmony between your soul and your life. May the mansions of your soul never become a haunted place. May you know the eternal longing that is at the heart of time. May there be kindness in your gaze to look within. May you never place walls between the light and yourself. May your angel free you from the prisons of fear, guilt, disappointment and despair. May you allow the wild beauty of the invisible world to gather you, mind you and embrace you in belonging. From Eternal Echoes, John O’Donohue Congratulations Helge and Reidunn! On 22nd July, Helge and Reidunn Hedetoft of Hogganvik will celebrate 50 years of marriage. And on 8th August, Reidunn will celebrate his 80th birthday. They have been connected with Camphill for over 50 years, being part of the initiative group for the found- ing of Vidarasen. Later they were part of the ‘founding fathers’ of Hogganvik and have been connected ever since, though living mostly in nearby Vikedal. Till recently, Helge contributed in the office and the services, Reidunn with Norwegian lessons for foreigners, kindergarten and folkdancing. Helge still contributes with kindergarten and folkdancing, to everybody’s enjoyment. They are a very important part of the fabric of Hoggan- vik, who send congratulations, thanks and love. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M. -

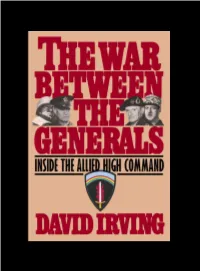

The War Between the Generals

THE WAR BETWEEN THE GENERALS DAVID IRVING F FOCAL POINT O Copyright © NVUN by David Irving Electronic version copyright © OMMP by Parforce UK Ltd. Excerpts from NVQM QR, by Martin Blumenson, are reprinted by kind permission of Houghton Mifflin Company. Copyright © NVTQ by Martin Blumenson All rights reserved á ABOUT THE AUTHOR David Irving is the son of a Royal Navy commander. Imperfectly educated at London’s Imperial College of Science & Technology and at University College, he subsequently spent a year in Germany working in a steel mill and perfecting his fluency in the language. In NVSP he published . This became a bestseller in many countries. Among his thirty books, the best-known include ; ; ; ! " #$ $; and % & ' (. The second volume of his ) appeared in OMMN; a third volume is in preparation. Many of his works are available as free downloads at www.fpp.co.uk/books. á CONTENTS PROLOGUE: Cover Plan.............................................................. N N Bedfellows ................................................................................ S O Uneasy Alliance....................................................................... NP P Alibi in Washington ...............................................................OV Q Stakes Incalculable..................................................................PS R Patton Meets His Destiny....................................................... RP S The Bomber Barons................................................................ST T -

Cohens Avishai, Anat Anat Avishai, Il Fam

DOWNBEAT Best CDs of 2011 John Scofield Peter Brötzmann 3 COHENS // JOHN JOHN Sc OFIEL D // PETER BRÖTZMANN PETER // BEST CDS OF 2011 Eric Reed BLINDFOLDED // SPECIAL SECTION JAZZ JAZZ JAZZ SCHOOL Sc HOOL » Charles Mingus TRANSCRIBED » Dr. Lonnie Smith MASTER CLASS » Jazz Camp Italian Style » Jim Snidero COHENS3 Avishai, Anat & Yuval JANUARY 2012 U.K. £3.50 FamILY CONQUERS ALL J ANUARY 2012 ANUARY DOWNBEAT.COM JANUARY 2012 VOLUme 79 – NUMBER 1 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

Karaoke Songs by Artist by Artist

Karaoke Songs by artist By Artist Artist Title <NO ARTIST> 19 SOMETHIN <NO ARTIST> BEER FOR MY HORSES <NO ARTIST> BREAKFAST AT TIFF <NO ARTIST> BURDON__ERIC___S <NO ARTIST> CARUSO <NO ARTIST> CHASING THAT NEON RAINBOW <NO ARTIST> CHE SARA <NO ARTIST> COME DANCING <NO ARTIST> DAYS GOES BY <NO ARTIST> DONT LET ME BE THE LAST TO KNOW <NO ARTIST> DONT SPEAK <NO ARTIST> FOREVER AND ALWAYS <NO ARTIST> FUNICULI FUNICULA <NO ARTIST> GIRLS LIE TOO <NO ARTIST> HAND IN POCKET <NO ARTIST> HAPPY BIRTHDAY VOCAL <NO ARTIST> HAVE YOU FORGOTTEN <NO ARTIST> HERE FOR THE PARTY <NO ARTIST> I MISS YOU A LITTLE <NO ARTIST> IM GONNA MISS HER <NO ARTIST> IN MY DAUGHTERS EYES <NO ARTIST> IN THE SUMMERTIME <NO ARTIST> IRONIC <NO ARTIST> ITS 5 OCLOCK SOMEWHERE <NO ARTIST> JERRY VALE - AL DI DA <NO ARTIST> LIVE LIKE YOU WERE DYING <NO ARTIST> MACARENA <NO ARTIST> MALA FEMMENA <NO ARTIST> MAMA <NO ARTIST> MARIJUANAVILLE <NO ARTIST> NATIONAL ANTHEM <NO ARTIST> NEL BLUE DIPINTO DI BLU <NO ARTIST> O SOLE MIO <NO ARTIST> ROTTERDAM <NO ARTIST> SANTA LUCIA <NO ARTIST> SHE TALKS TO ANGELS <NO ARTIST> SHES NOT THE CHEATIGN KIND <NO ARTIST> SPEAK SOFTLY LOVE <NO ARTIST> SUDS IN A BUCKET <NO ARTIST> SYLVIAS MOTHER <NO ARTIST> TARANTELLA <NO ARTIST> THATS AMORE <NO ARTIST> THERE GOES MY LIFE <NO ARTIST> THIRD RATE ROMANCE <NO ARTIST> TITLE <NO ARTIST> TORNA A SURRENTO <NO ARTIST> TWO OUT OF THREE AINT BAD <NO ARTIST> WALK ON THE WILD SIDE <NO ARTIST> WHEN THE SUN GOES DOWN <NO ARTIST> WHEN YOURE IN LOVE WITH A BEAUTIFUL WOMAN <NO ARTIST> WHOS CHEATING WHO <NO ARTIST> YOU REALLY