Lying in Familial Relationships As Portrayed in Domestic Sitcoms Since the Recession: an Examination of Family Structure and Economic Class

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Power Seeking and Backlash Against Female Politicians

Article Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin The Price of Power: Power Seeking and 36(7) 923 –936 © 2010 by the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc Backlash Against Female Politicians Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0146167210371949 http://pspb.sagepub.com Tyler G. Okimoto1 and Victoria L. Brescoll1 Abstract Two experimental studies examined the effect of power-seeking intentions on backlash toward women in political office. It was hypothesized that a female politician’s career progress may be hindered by the belief that she seeks power, as this desire may violate prescribed communal expectations for women and thereby elicit interpersonal penalties. Results suggested that voting preferences for female candidates were negatively influenced by her power-seeking intentions (actual or perceived) but that preferences for male candidates were unaffected by power-seeking intentions. These differential reactions were partly explained by the perceived lack of communality implied by women’s power-seeking intentions, resulting in lower perceived competence and feelings of moral outrage. The presence of moral-emotional reactions suggests that backlash arises from the violation of communal prescriptions rather than normative deviations more generally. These findings illuminate one potential source of gender bias in politics. Keywords gender stereotypes, backlash, power, politics, intention, moral outrage Received June 5, 2009; revision accepted December 2, 2009 Many voters see Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton as coldly politicians and that these penalties may be reflected in voting ambitious, a perception that could ultimately doom her presi- preferences. dential campaign. Peter Nicholas, Los Angeles Times, 2007 Power-Relevant Stereotypes Power seeking may be incongruent with traditional female In 1916, Jeannette Rankin was elected to the Montana seat in gender stereotypes but not male gender stereotypes for a the U.S. -

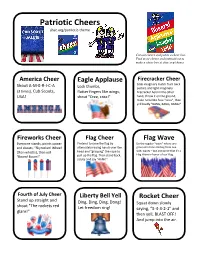

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

Evidence-Based Parenting

Evidence-Based Parenting April 3, 2021 Leonard Sax MD PhD www.leonardsax.com You can reach me at [email protected] (scroll to the bottom of the document for complete contact information). The established consensus in 1964: encourage immigrant children to assimilate as soon as possible. For the scholarship underlying this consensus, see Milton Gordon’s monograph Assimilation in American Life: the role of race, religion, and national origins, New York: Oxford University Press, 1964. Because of this long-held consensus, the more recent finding that immigrant children now do better than American-born children is regarded as evidence of a “paradox.” Scroll to the bottom of this document for citations documenting the immigrant paradox. Disclaimers: I am not endorsing Dr. Gordon’s recommendations. 1964 was not the good old days; that era was much more racist and sexist than our own. Every era has its challenges. The first two graphs I showed – demonstrating a marked in the proportion of people reporting either a major depressive episode, or serious psychological distress, 2009 to 2017 – with that rise seen among adolescents age 12 to 17, and young adults age 18 to 25, but not in older age groups – is taken from the paper by Jean Twenge and colleagues, “Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005 – 2017,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, April 2019, full text online at https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2019-12578-001. A comprehensive review of current scholarly literature documenting a recent rise in adolescent mood disorders, co-edited by Professor Twenge, is online at https://tinyurl.com/TeenMentalHealthReview. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

DRAGONS ABREAST – Keeping the Spirit Alive! One Journey — Many

Dragons Abreast ACT & Region www.dragonsabreast.com.au Abreast of the news newsletter Under the umbrella of Breast Cancer Network Australia P.O. Box 7191 Yarralumla ACT 2600 Issue 31 May 2009 15th UICC Reach to Recovery International Breast Cancer Support Conference One journey — many people Brisbane Convention Centre, Brisbane 13-15 May 2009 http://www.reachtorecovery2009.org/ Report by Kerrie Griffin Introduction You are not alone was a recurring theme as Sincere thanks to Dragons Abreast ACT who inspiring speakers spoke of the amazing research sponsored my participation at the Reach to and support networks happening around the world. Recovery International conference. I’ve included The plenary and workshop speakers were hyperlinks to relevant resources for your future professionals of a very high calibre who were able reference. Here is my summary of the plenary to translate complex research findings for the sessions and workshops that I attended which was layperson in a relevant and succinct fashion. only a small part of this enormous conference. It was difficult to chose from so many topics. Many Professor Jeff Dunn, Conference Chair and CEO thanks to Bea Brickhill, DA ACT, a recently Cancer Council Queensland, spoke of the diagnosed friend, for sharing the journey with me infectious buzz at any breast cancer meeting but as well as providing her notes on the media especially at this conference as women networked workshop. I enjoyed meeting and mingling with and shared support. He said the conference had many new, kind and generous people from around the international spirit of common goals, working the world and Australia, including the ACT. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Cheers, Friends! the Story of Our Beer Zlatý Bažant 12° Tank

The story of our beer Zlatý Bažant 12° tank beer artfully brewed Superior ingredients are not enough when it comes to beer brewing. The thing that really counts is the craftsmanship of beer masters who keep an eye on the whole brewing process. They are experts who love their job and whose passion for beer and experience can’t be replaced by any modern machine. They brew Zlatý Bažant 12 artfully for you. Stored with care Zlatý Bažant is delivered to Klubovňa in a temperature stable tank right from the brewery. Afterwards it is pumped into smaller beer bags in our beautiful and modern stainless steel tanks. These beer bags are changed after each such filling in order to keep the beer in the best conditions. We keep beer chilled to ideal temperature of 7-10°C all the way. When your Bažant is draught from the tank, it is being pushed up by a compressor which pushes the air on the beer bag inside the tank. Doing it this way ensures that our artfully brewed Zlatý Bažant 12° tank beer will never get in touch with air, which guarantees the best beer quality on its way from brewery right into your glass. Artfully draught, served and enjoyed Brewing beer is a science. And drawing beer correctly is an art. Enjoy this premium lager beer of Pilsner type produced by traditional technology. It has a prominent well-balanced full taste, strong hops aroma and a pleasant bitter aftertaste. The malt from own malt plant provides it with the deep yellow color. -

Cougar Town S02 Vostfr

Cougar town s02 vostfr click here to download Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV Cpasbien permet de télécharger des torrents de films, séries, musique, logiciels et jeux. Accès direct à torrents . Cougar Town S06E09 VOSTFR HDTV Cpasbien permet de télécharger des torrents de films, séries, musique, logiciels et jeux. Accès direct à torrents . Chicago Fire S03E02 VOSTFR HDTV, Mo, 5, 0. Castle S07E01 VOSTFR HDTV, Mo, 1, 1. Chicago Fire Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 13, 8. Chicago Fire Saison Cougar Town S05E13 FINAL FRENCH HDTV, Mo, 2, 0. Charmed Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 10, 5 Chicago PD Saison 1 VOSTFR HDTV, Go, 2, 2 Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 4, 2. 24 Heures Chrono - Saison 2 Beverly Hills Nouvelle Génération - Saison 2 A Young Doctor's Notebook - Saison 2 .. Cougar Town - Saison 2. www.doorway.ru season 2 p — omcougar-town-seasonepisode-2 Hosts: Filenuke Movreel Sharerepo www.doorway.ruS04Ep. cougar town s05e09 p-mifydu's blog. www.doorway.rulm. www.doorway.ruilm. www.doorway.rup. Cougar Town/Cougar Town_S01/www.doorway.ru, MB. Cougar Town/Cougar Town_S01/www.doorway.rulm. Routine Her Amazed, Thing in dallas vostfr s02 Little Mansion was my first Sue s02 Dallas vostfr s02 href="www.doorway.ru Season 1, Season 2, Season 3, Season 4. Release Year: In Season 1, Detective Gordon tangles with unsavory crooks and supervillains in Gotham City . Cougar Town Saison 1 FRENCH HDTV, GB, 66, Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, GB, 51, 6. Cougar Town S03E01 VOSTFR HDTV, Saison 2 · Liste des épisodes · modifier · Consultez la documentation du modèle. -

PRESCRIPTION DRUG COUPON STUDY Report to the Massachusetts Legislature JULY 2020

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS HEALTH POLICY COMMISSION PRESCRIPTION DRUG COUPON STUDY Report to the Massachusetts Legislature JULY 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In this report, required by Chapter 363 of the 2018 Session Prescription drug coupons are currently allowed in all 50 Laws, the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission (HPC) states for commercially-insured patients. Federal health examines the use and impact of prescription drug coupons insurance programs, such as Medicare, Medicaid, Tricare in Massachusetts. This report focuses on coupons issued by and Veteran’s Administration, prohibit the use of coupons pharmaceutical manufacturers that reduce a commercial based on federal anti-kickback statutes. Massachusetts patient’s cost-sharing. Prescription drug coupons are offered became the last state to authorize commercial coupon use almost exclusively on branded drugs, which comprise only in 2012 but continues to prohibit manufacturers from 10% of all prescriptions dispensed in the U.S., but account offering coupons and discounts on any prescription drug for 79% of total drug spending. Despite the immediate ben- that has an “AB rated” generic equivalent as determined efit of drug coupons to patients, policymakers and experts by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The 2012 debate whether and how coupons should be allowed in the law authorizing coupons in Massachusetts also contained commercial market given the potential relationship between a sunset provision, under which the law would have been coupon usage and increased spending on branded drugs repealed on July 1, 2015. However, this date of repeal versus lower cost alternatives. was postponed several times and ultimately extended to January 1, 2021. Massachusetts has long sought to con- Coupons reduce or eliminate the patient’s cost-sharing sider the impact of drug coupons on the Commonwealth’s responsibility required by the patient’s insurance plan, while landmark cost containment goals, as well as the benefits for the plan’s costs for the drug remain unchanged. -

From Disney to Disaster: the Disney Corporation’S Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks

From Disney to Disaster: The Disney Corporation’s Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks BY Kelsey N. Reese Spring 2021 WMNST 492W: Senior Capstone Seminar Dr. Jill Wood Reese 2 INTRODUCTION The popularized phrase “celebrity trainwreck” has taken off in the last ten years, and the phrase actively evokes specified images (Doyle, 2017). These images usually depict young women hounded by paparazzi cameras that are most likely drunk or high and half naked after a wild night of partying (Doyle, 2017). These girls then become the emblem of celebrity, bad girl femininity (Doyle, 2017; Kiefer, 2016). The trainwreck is always a woman and is usually subject to extra attention in the limelight (Doyle, 2017). Trainwrecks are in demand; almost everything they do becomes front page news, especially if their actions are seen as scandalous, defamatory, or insane. The exponential growth of the internet in the early 2000s created new avenues of interest in celebrity life, including that of social media, gossip blogs, online tabloids, and collections of paparazzi snapshots (Hamad & Taylor, 2015; Mercer, 2013). What resulted was 24/7 media access into the trainwreck’s life and their long line of outrageous, commiserable actions (Doyle, 2017). Kristy Fairclough coined the term trainwreck in 2008 as a way to describe young, wild female celebrities who exemplify the ‘good girl gone bad’ image (Fairclough, 2008; Goodin-Smith, 2014). While the coining of the term is rather recent, the trainwreck image itself is not; in their book titled Trainwreck, Jude Ellison Doyle postulates that the trainwreck classification dates back to feminism’s first wave with Mary Wollstonecraft (Anand, 2018; Doyle, 2017). -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible.