Political Constructions of Transnational EU Migrants in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How We Best Respond to the Challenges and Opportunities of an Ageing Population

Summary of Submissions to the Citizens’ Assembly on the second topic for consideration How we best respond to the Challenges and Opportunities of an Ageing Population 1 Contents Page Submissions Process....................................................................................... 3 The Numbers.................................................................................................. 3 Key Issues arising from Submissions 1. Long-Term Care including End of Life Care........................................... 4 2. Pensions, Income and Retirement....................................................... 6 3. Leadership and Implementation.......................................................... 6 4. Health, Mobility and Transport............................................................ 7 5. Participation/Inclusion/ Ageism.......................................................... 8 6. Elder Abuse......................................................................................... 9 7. Technology......................................................................................... 9 8. Housing.............................................................................................. 10 9. Demographics..................................................................................... 10 10. Education............................................................................................ 11 Appendix 1 – Submissions made by Advocacy Groups and Professionals/Academics 2 Submissions Process The submissions process -

National Library of Ireland

ABOUT TOWN (DUNGANNON) AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) No. 1, May - Dec. 1986 Feb. 1950- April 1951 Jan. - June; Aug - Dec. 1987 Continued as Jan.. - Sept; Nov. - Dec. 1988 AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Jan. - Aug; Oct. 1989 May 1951 - Dec. 1971 Jan, Apr. 1990 April 1972 - April 1975 All Hardcopy All Hardcopy Misc. Newspapers 1982 - 1991 A - B IL B 94109 ADVERTISER (WATERFORD) AISÉIRÍ (DUBLIN) Mar. 11 - Sept. 16, 1848 - Microfilm See AISÉIRGHE (DUBLIN) ADVERTISER & WATERFORD MARKET NOTE ALLNUTT'S IRISH LAND SCHEDULE (WATERFORD) (DUBLIN) March 4 - April 15, 1843 - Microfilm No. 9 Jan. 1, 1851 Bound with NATIONAL ADVERTISER Hardcopy ADVERTISER FOR THE COUNTIES OF LOUTH, MEATH, DUBLIN, MONAGHAN, CAVAN (DROGHEDA) AMÁRACH (DUBLIN) Mar. 1896 - 1908 1956 – 1961; - Microfilm Continued as 1962 – 1966 Hardcopy O.S.S. DROGHEDA ADVERTISER (DROGHEDA) 1967 - May 13, 1977 - Microfilm 1909 - 1926 - Microfilm Sept. 1980 – 1981 - Microfilm Aug. 1927 – 1928 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1982 Hardcopy O.S.S. 1929 - Microfilm 1983 - Microfilm Incorporated with DROGHEDA ARGUS (21 Dec 1929) which See. - Microfilm ANDERSONSTOWN NEWS (ANDERSONSTOWN) Nov. 22, 1972 – 1993 Hardcopy O.S.S. ADVOCATE (DUBLIN) 1994 – to date - Microfilm April 14, 1940 - March 22, 1970 (Misc. Issues) Hardcopy O.S.S. ANGLO CELT (CAVAN) Feb. 6, 1846 - April 29, 1858 ADVOCATE (NEW YORK) Dec. 10, 1864 - Nov. 8, 1873 Sept. 23, 1939 - Dec. 25th, 1954 Jan. 10, 1885 - Dec. 25, 1886 Aug. 17, 1957 - Jan. 11, 1958 Jan. 7, 1887 - to date Hardcopy O.S.S. (Number 5) All Microfilm ADVOCATE OR INDUSTRIAL JOURNAL ANOIS (DUBLIN) (DUBLIN) Sept. 2, 1984 - June 22, 1996 - Microfilm Oct. 28, 1848 - Jan 1860 - Microfilm ANTI-IMPERIALIST (DUBLIN) AEGIS (CASTLEBAR) Samhain 1926 June 23, 1841 - Nov. -

Publications

Publications National Newspapers Evening Echo Irish Examiner Sunday Business Post Evening Herald Irish Field Sunday Independent Farmers Journal Irish Independent Sunday World Irish Daily Star Irish Times Regional Newspapers Anglo Celt Galway City Tribune Nenagh Guardian Athlone Topic Gorey Echo New Ross Echo Ballyfermot Echo Gorey Guardian New Ross Standard Bray People Inish Times Offaly Express Carlow Nationalist Inishowen Independent Offaly Independent Carlow People Kerryman Offaly Topic Clare Champion Kerry’s Eye Roscommon Herald Clondalkin Echo Kildare Nationalist Sligo Champion Connacht Tribune Kildare Post Sligo Weekender Connaught Telegraph Kilkenny People South Tipp Today Corkman Laois Nationalist Southern Star Donegal Democrat Leinster Express Tallaght Echo Donegal News Leinster Leader The Argus Donegal on Sunday Leitrim Observer The Avondhu Donegal People’s Press Letterkenny Post The Carrigdhoun Donegal Post Liffey Champion The Nationalist Drogheda Independent Limerick Chronnicle Tipperary Star Dublin Gazette - City Limerick Leader Tuam Herald Dublin Gazette - North Longford Leader Tullamore Tribune Dublin Gazette - South Lucan Echo Waterford News & Star Dublin Gazette - West Lucan Echo Western People Dundalk Democrat Marine Times Westmeath Examiner Dungarvan Leader Mayo News Westmeath Independent Dungarvan Observer Meath Chronnicle Westmeath Topic Enniscorthy Echo Meath Topic Wexford Echo Enniscorthy Guardian Midland Tribune Wexford People Fingal Independent Munster Express Wicklow People Finn Valley Post Munster Express Magazines -

Irish Political Review, July 2010

Bloody Sunday Jack Jones Wrecking E S B ? Conor Lynch And The Spies Labour Comment Manus O'Riordan page 6 page 21 back page IRISH POLITICAL REVIEW July 2010 Vol.25, No.7 ISSN 0790-7672 and Northern Star incorporating Workers' Weekly Vol.24 No.7 ISSN 954-5891 Coping With The Future The gEUru Returns We Failed To Prevent The guru of the concept of the EU Progressive Governments must not be inward looking. The principle of Sinn Fein, if Constitution-cum-Lisbon Treaty is Valery it was ever progressive, has long been reactionary and stultifying, and the inaccurate Giscard d'Estaing. When the current translation of it as "Ourselves Alone" expresses the essential truth about it. Ireland, in existential crisis of the EU manifested order. to be modern, must be open to the world so that the world might be open to it. Its itself with the defeat of the Nice Treaty in dynamic must be an integral part of the dynamic of the world market. Ireland almost a decade ago, he came up And yet, when the world market goes awry with drastic consequences for Ireland, the with the brilliant idea of a piece of paper Government—which did what was required of it by the progressive forces—is to be held that would cover all the cracks and responsible because it did what was required of it. persuade all that the EU was going from strength to strength. A pompous, long The Government must do what the people wants. That's democracy. But, when what winded, legalistic piece of constitution- the people wanted leads to disaster, it is the Government that is to blame. -

Plean Scoile St. Paul's N.S

Plean Scoile Plean Scoile St. Paul’s N.S., Dooradoyle, Limerick Under the Patronage of the Bishop of Limerick. Most Recent Update: October 2018 This is a working document that is being developed by the School Community. It is constantly reviewed at Staff Meetings, on ‘Revised Curriculum’ in-service and SDP days It is the process by which we educate our children in St. Paul’s N.S. As part of the self analysis, the school community shall, when opportunities arise, evaluate the plan under the following criteria: 1. School Administration 2. School Planning 3. Curriculum Implementation Contents: Page The Process of the School Plan 3 Mission Statement 4 Introduction to St Paul’s NS 5 Accommodation with our school 7 Aims and Objectives of St Paul’s NS 8 Board of Management 9 Home-School Liaison (and Parents’ Association) 10 St Paul’s NS Staff 12 Ancillary Staff 13 The Principal 14 Posts of Responsibility 16 Communication 22 Policy Documents 23 1. Enrolment 23 2. Learning-Support Provision (Including EAL provision) 23 3. Parent/Teacher 48 4. Supervision 48 5. Break time Supervision/Sanctions 49 6. Homework 49 7. Intercultural 50 8. Attendance 52 9. Child Protection Policy 53 10. Bullying 63 11. Acceptable Use (IT) 66 12. Administration of Medicines to Children 68 13. Equality of Access and Participation 69 14. Health and Safety 73 15. Record Keeping and Data Protection 80 16. Staff Relations 82 17. Staff Development 86 18. Substance Abuse 88 19. Ancillary Staff 90 20. Healthy Eating 92 21. Assessment 94 Code of Conduct 99 School Day 103 After School Use of Facilities – Hall & School 105 Development Plan 106 Review Schedule 113 List of Meetings (School Planning) 116 Curricular Areas English 120 Mathematics 154 Gaeilge 178 History 202 Geography 217 Science 231 SPHE 245 Visual Arts 260 Music 269 Drama 280 PE 293 ICT 315 Comenius Project 328 Planning Templates 333 Dates of Completed Reviews 350 2 The Process of School Plan The process of the school plan has taken shape from the school year beginning 2000 up to now (June 2008). -

A Chronicle of Limerick Life

A Chronicle of Limerick life As far back as 1690, when William I11 was besieging the then walled city, a Paris reprint is the authority for stating that a book by an Irish Capuchin priest was ~rin- ted in Limerick at that time. The next Limerick book by W.W. Gleeson recorded is "The Libertine School'd" which was printed by Samuel Terry & Boxon in 1722. Whilst it would be futile to attempt provide a constant guide to a domain of the numerous commericial, or job, printing houses that flourished in Limerick, since Caxton introduced to Westminster in 1476 the "Art, Greatest of all Arts", it goes without saying that the Shannonside city was well served with news down the years, as the follow- ing list shows. 1716The Limerick Newsletter, 1739-The Limerick Journal, 1749-Munster Journal, 1766The Limerick Chronicle, 1779-The Limerick Journal, 1788-The Limerick Herald and Munster Advertiser, 1790-The Limerick Weekly Magazine, 1804--The General Adver- ttzer , 1804-The General Advertizer or Limerick Gazette, 1811-The Limerick Evening Post, 1819-The Munster Telegraph, 1822-The Limerick News, 182CThe Irish Observer, 1831-The Limerick Herald, 1832-The Munster Journal and Limerick Commericial Reporter, 1833-The Limerick Guardian, 1834-The Limerick Times, 1837-The Limerick Standard, 1845-The Limerick and Clare Examiner, 185bThe Limerick Reporter and Tipperary Vindicator, 1851-The Munster News, 1853-The Limerick Herald, 1856-The Limerick Observer, The Limerick/Tipperary/Waterford Examiner 1863-The Southern Chronicle, 1867-The Citizens Paper, 1887-The Daily Southern Advertizer 1889-The Limerick Leader. 1893-The Limerick Star, 1898-The Limerick Echo, 1917-The Limerick Herald, 1923-The Limerick Herald, 1937-3LThe Limerick Herald. -

An Evaluation of the Digital Strategies of Irish News Organisations

Irish Communication Review Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 5 January 2014 Untangling the Web: an Evaluation of the Digital Strategies of Irish News Organisations Paul Hyland Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons Recommended Citation Hyland, Paul (2014) "Untangling the Web: an Evaluation of the Digital Strategies of Irish News Organisations," Irish Communication Review: Vol. 14: Iss. 1, Article 5. doi:10.21427/D7P716 Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/icr/vol14/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Current Publications at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Communication Review by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License UNTANGLING THE WEB: An evaluation of the digital strategies of Irish news organisations Paul Hyland Introduction As Ireland’s print media continue to suffer a drop in their circulations, how impor- tant is the implementation of a viable and, above all, profitable web strategy, and how extensively are these currently being employed within four Irish news organisations? These include Ireland’s three best selling dailies: The Irish Times, the Irish Independent, and the Irish Daily Star, and a regional newspaper with a notable online presence, the Limerick Leader. This research examines the day-to-day operations of Irish news organisations; the resources devoted to their digital media/online departments, the revenue-generation strategies in place to monetize the work of these departments; and the prioritization given to the various mediums through which information is distributed. -

News Distribution Via the Internet and Other New Ict Platforms

NEWS DISTRIBUTION VIA THE INTERNET AND OTHER NEW ICT PLATFORMS by John O ’Sullivan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA by Research School of Communications Dublin City University September 2000 Supervisor: Mr Paul McNamara, Head of School I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of MA in Communications, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. I LIST OF TABLES Number Page la, lb Irish Internet Population, Active Irish Internet Population 130 2 Average Internet Usage By Country, May 2000 130 3 Internet Audience by Gender 132 4 Online Properties in National and Regional/Local Media 138 5 Online Properties in Ex-Pat, Net-only, Radio-related and Other Media 139 6 Journalists’ Ranking of Online Issues 167 7 Details of Relative Emphasis on Issues of Online Journalism 171 Illustration: ‘The Irish Tex’ 157 World Wide Web references: page numbers are not included for articles that have been sourced on the World Wide Web, and where a URL is available (e.g. Evans 1999). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS With thanks and appreciation to Emer, Jack and Sally, for love and understanding, and to my colleagues, fellow students and friends at DCU, for all the help and encouragement. Many thanks also to those who agreed to take part in the interviews. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. I n t r o d u c t i o n ......................................................................................................................................................6 2. -

AONTAS Annual Report 2004

AONTAS AONTAS National Association Education National of Adult ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2004 AONTAS National Association of Adult Education 2nd Floor, 83 – 87 Main Street, Ranelagh, Dublin 6 Tel: 01 406 8220/1 Fax: 01 406 8227 Email: [email protected] Website: www.aontas.com AONTAS MiSSiON AONTAS is the National Association of Adult Education, a voluntary membership organisation. it exists to promote the development of a learning society through the provision of a quality and comprehensive system of adult education which is accessible to and inclusive of all. The five objectives of the current AONTAS Strategic Plan, Sustaining Growth and Development 2004-2006, are: Ensuring that the importance and value of adult and community education as a key part of lifelong learning are promoted locally, nationally and internationally Influencing and participating in the continued development of policy in the areas of adult education, lifelong learning and civil society Strengthening and building the capacity of members to operate effectively in the growth and development of the Adult Education Service Taking a lead role in supporting the growth and development of community education as a key sector providing access and progression for adult learners Developing the capacity of AONTAS as a learning organisation and a model of excellence for the Adult and Community Education sector AnnuAl RepoRt & Accounts 2004 01 contents Foreword 05 Overview 07 Policy Development and Advocacy 11 AONTAS Membership Services 25 AONTAS Information Service 31 Promoting and Profiling AONTAS and Adult Education 37 Research 41 Other Programmes 43 Executive Committee 47 Staff 48 Membership List 49 Financial Statements 59 FoRewoRd At the end of the first year of my second term as President of AONTAS I am glad to say that I am more optimistic than at the beginning. -

Behind the Headlines: Media Coverage of Social Exclusion in Limerick City – the Case of Moyross

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Limerick Institutional Repository Behind The Headlines: Media Coverage of Social Exclusion in Limerick City – The Case of Moyross Eoin Devereux, Amanda Haynes and Martin J. Power Introduction 1 In a media setting, and within the public mind, Ireland’s ‘Third City’ has acquired an intensely negative reputation over time. While there are many historical precedents for the maligning of the place’s image, it is generally agreed that the 1980s reached a new low within media practice with the ascription, in some media quarters, of the label ‘Stab City’ to Limerick. The blanket representation of Limerick as a place of crime, social disorder, poverty and social exclusion has continued and it has been amplified in recent years, particularly in the context of the feuds between rival drugs gangs, most of which have been played out in the city’s marginalized local authority estates such as Moyross, St. Mary’s Park, Southill and Ballinacurra Weston. Understandably, a variety of interest groups have expressed concern over the ways in which Limerick generally and marginalized areas in particular have been misrepresented by the mass media 2. Our focus in this chapter is not on the veracity or not of individual stories about Limerick, but rather our task is to get behind the headlines and to examine, in detail, the making of media messages concerning one socially excluded area in Limerick City, namely Moyross. We focus on the role of print and broadcast media professionals in the (mis)representation of this area. -

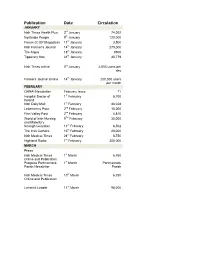

National Media Report 2017

Publication Date Circulation JANUARY Irish Times Health Plus 3rd January 74,092 Northside People 9th January 120,000 Forum (ICGP Magazine) 11th January 3,500 Irish Farmer’s Journal 14th January 279,000 The Argus 18th January 8500 Tipperary Star 31st January 40,779 Irish Times online 3rd January 4,853 users per day Farmers Journal Online 14th January 200,000 users per month FEBRUARY OHNAI Newsletter February Issue ?? Hospital Doctor of 1st February 5,700 Ireland Irish Daily Mail 1st February 46,028 Letterkenny Post 2nd February 15,000 Finn Valley Post 2nd February 4,810 World of Irish Nursing 9TH February 38,000 and Midwifery Nenagh Guardian 11th February 6,502 The Irish Catholic 16th February 28,000 Irish Medical Times 24th February 6,750 Highland Radio 1st February 300,000 MARCH Press Irish Medical Times 1st March 6,750 Online and Publication Progress Portmarnock 1st March Portmarnock Parish Newsletter Parish Irish Medical Times 10th March 6,750 Online and Publication Limerick Leader 11th March 98,000 Publication Date Circulation Online th www.irishhealth.com 16 March 160,000 users Laois People 20th March 10,676 readers The Irish Independent 27th March 102,537 Laois Nationalist 28th March Tallaght Echo 30th March 12,000 readers Ballyfermont Echo 30th March 4,000 readers Lucan Echo 30th March 4,000 readers Clondalkin Echo 30th March 4,000 readers April 69,000 avg daily LMFM Radio 1st to 5th April listenership Irish Pharmacy News 13th April 1020 readers 13,000 www.activelink.ie 18th April subscribers The Galway Advertiser 20th April 29,026 The Clare Champion 21st April 17,000 readers The Clare Champion 23rd April 17,000 readers The Irish Times 25th April 72,011 The Clare Courier 28th April 8,753 The Nenagh Guardian 29th April 6502 Migraine Newsletter. -

By John Bruton

CONTENTS ABOUT THE EIF •02 DAY 1: OPENING AND KEYNOTE ADDRESSES •04 by Wilfried Martens and Antonio Tajani PANEL I •08 Europe in the World Economy: Winning Opportunities through stronger Economic Governance KEYNOTE SPEECH •14 by John Bruton PANEL II •16 How can Europe bounce back? The Single Market as the Key to Growth PANEL III •22 Boosting Competitiveness and enhancing social Europe: How to deliver on both Fronts? DAY 2: OPENING •28 by Elmar Brok PANEL IV •30 A transatlantic Panel: The EU and US – Shared Economic Challenges KEYNOTE SPEECH •36 by Enda Kenny PANEL V •38 A Political Union now? Towards a more integrated Europe – A Panel of European Affairs Ministers CLOSING OF THE EIF •44 WORKING GROUPS •45 IDEAS TO MOVE FORWARD •46 SPEAKERS AT THE EIF •48 OUR PARTNERS •52 OUR SPONSORS •53 EIF IN THE PRESS •54 EIF POLITICAL CARTOONS •56 INTERACTIVE EIF •58 WHY SPONSOR US? •59 CREDITS •60 C E S 01 C E S CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN STUDIES www.thinkingeurope.eu Dublin '12 ABOUT THE EIF In April 2012 the Centre for European Studies was proud to host the third annual EIF12 took place in Dublin on the 19th and 20th of April As Europe continues to struggle, fresh ideas are urgently and brought together experts and policymakers from needed for revitalising the economy, generating growth across Europe and beyond. Participants included EU and creating jobs. This unique gathering of speakers and officials, parliamentarians and senior Irish politicians, as participants provided an ideal opportunity to discuss cur- well as high-level representatives of major corporations.