The Banking Sector 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

联合国安全理事会综合制裁名单文件生成日期: 29 October 2018 文件

Res. List 联合国安全理事会综合制裁名单 文件生成日期: 29 October 2018 文件生成日期是指用户查阅名单的日期,不是制裁名单最近实质性更新日期。有关名单实质性更新的信息载于委员会 网站。 名单的构成 名单由两部分组成,具体如下: A. 个人 B. 实体和其他团体 有关除名的信息见以下网站: https://www.un.org/sc/suborg/zh/ombudsperson (第1267号决议) https://www.un.org/sc/suborg/zh/sanctions/delisting (其他委员会) https://www.un.org/zh/sc/2231/list.shtml (第2231号决议) A. 个人 KPi.033 名称: 1: RI 2: WON HO 3: 4: 无 职称: 无 头衔: 朝鲜国家安全保卫部官员 出生日期: 17 Jul. 1964 出生地点: 无 足够确认身份的别名: 无 不足确认身 份的别名: 无 国籍: 朝鲜民主主义人民共和国 护照编号: 381310014 国内身份证编号: 无 地址: 无 列入名单日期: 30 Nov. 2016 其他信息: Ri Won Ho是朝鲜国家安全保卫部官员,派驻叙利亚以支持朝鲜矿业发展贸易公司。 KPi.037 名称: 1: CHANG 2: CHANG HA 3: 4: 无 职称: 无 头衔: 第二自然科学院院长 出生日期: 10 Jan. 1964 出生地点: 无 足够确认身份的别名: Jang Chang Ha 不 足确认身份的别名: 无 国籍: 朝鲜民主主义人民共和国 护照编号: 无 国内身份证编号: 无 地址: 无 列入名单日期: 30 Nov. 2016 其他信息: KPi.038 名称: 1: CHO 2: CHUN RYONG 3: 4: 无 职称: 无 头衔: Cho Chun Ryong是第二经济委员会的主席。 出生日期: 4 Apr. 1960 出生地点: 无 足够确认身份的别 名: Jo Chun Ryong 不足确认身份的别名: 无 国籍: 朝鲜民主主义人民共和国 护照编号: 无 国内身份证编号: 无 地址: 无 列入名单日期: 30 Nov. 2016 其他信息: KPi.034 名称: 1: JO 2: YONG CHOL 3: 4: 无 职称: 无 头衔: 朝鲜国家安全保卫部官员 出生日期: 30 Sep. 1973 出生地点: 无 足够确认身份的别名: Cho Yong Chol 不足确认身份的别名: 无 国籍: 朝鲜民主主义人民共和国 护照编号: 无 国内身份证编号: 无 地址: 无 列入名单日 期: 30 Nov. 2016 其他信息: Jo Yong Chol是朝鲜国家安全保卫部官员,派驻在叙利亚支持朝鲜矿业发展贸易公司。 KPi.035 名称: 1: KIM 2: CHOL SAM 3: 4: 无 职称: 无 头衔: 大同信贷银行的代表 出生日期: 11 Mar. 1971 出生地点: 无 足够确认身份的别名: 无 不足确认身份的 别名: 无 国籍: 朝鲜民主主义人民共和国 护照编号: 无 国内身份证编号: 无 地址: 无 列入名单日期: 30 Nov. 2016 其 他信息: Kim Chol Sam是大同信贷银行的代表,参与管理为大同信贷银行金融有限公司进行的交易。作为大同信贷银 行的海外代表,Kim Chol Sam涉嫌协助多项价值数十万的交易,可能管理着朝鲜境内数百万美元的账户,这些账户可 能与核/导弹计划有关。 KPi.036 名称: 1: KIM 2: SOK CHOL 3: 4: 无 职称: 无 头衔: a) 担任朝鲜驻缅甸大使 b) 为朝鲜矿业发展贸易公司提供协助 出生日期: 8 May 1955 出生地点: 无 足 够确认身份的别名: 无 不足确认身份的别名: 无 国籍: 朝鲜民主主义人民共和国 护照编号: 472310082 国内身份证编 号: 无 地址: 无 列入名单日期: 30 Nov. -

Annual Report 2019

NUMBERSTALK 9Annual Report 2019 BAHRAIN KUWAIT UAE UK EGYPT IRAQ OMAN 9LIBYA Constantly striving to provide greater levels of shareholder and customer satisfaction by delivering ever higher 9standards of performance % increase in Total Assets to US$ 40.3 billion 13.4 compared to 2018 % increase in Net Profit to US$ 730.5 million 4.7 compared to 2018 % increase in Shareholders’ Equity to US$ 4.3 billion 9.1 compared to 2018 Ahli United Bank Annual Report 2019 02 CONTENT 04 06 GROUP MISSION STATEMENT AUB OPERATING DIVISIONS 08 16 18 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS BOARD OF DIRECTORS’ REPORT BOARD OF DIRECTORS 22 24 27 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT GROUP CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER & CORPORATE GOVERNANCE MANAGING DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT 48 55 56 GROUP BUSINESS AND RISK REVIEW GROUP MANAGEMENT GROUP MANAGEMENT ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE 59 61 131 CONTACT DETAILS CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL PILLAR III DISCLOSURES - BASEL III STATEMENTS Ahli United Bank Annual Report 2019 03 Group Mission Statement To create an unrivalled ability to meet customer needs, provide fulfilment and development for our staff and deliver outstanding shareholder value. Ahli United Bank Annual Report 2019 04 OBJECTIVES AUB VISION & STRATEGY • to maximise shareholder value on a sustainable basis. • Develop an integrated pan regional financial services • to maintain the highest international standards of corporate group model centered on commercial and retail banking, governance and regulatory compliance. private banking, asset management and life insurance with an enhanced Shari’a compliant business contribution. • to maintain solid capital adequacy and liquidity ratios. • Acquire banks and related regulated financial institutions in • to entrench a disciplined risk and cost management the Gulf countries (core markets) with minimum targeted culture. -

UNITED NATIONS Security Council

UNITED S NATIONS Security Council Distr. GENERAL S/AC.26/2000/17 29 September 2000 Original: ENGLISH UNITED NATIONS COMPENSATION COMMISSION GOVERNING COUNCIL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS MADE BY THE PANEL OF COMMISSIONERS CONCERNING THE FIFTH INSTALMENT OF “E2” CLAIMS GE.00-63685 S/AC.26/2000/17 Page 2 Contents Paragraphs Page Introduction..................................................... 1 - 3 6 I. OVERVIEW OF THE CLAIMS...................................... 4 - 6 7 II. PROCEDURAL MATTERS.......................................... 7 - 14 8 III. LEGAL ISSUES............................................... 15 – 32 10 A. General purpose loans ................................... 18 – 20 10 B. Specific purpose loans .................................. 21 – 22 11 C. Rescheduled loans ....................................... 23 – 25 12 D. Guarantees .............................................. 26 – 27 12 E. Letters of Credit ....................................... 28 – 30 13 F. Refinancing arrangements ................................ 31 – 32 13 IV. REVIEW OF THE CLAIMS PRESENTED.............................. 33 – 152 15 A. Contracts involving Iraqi parties ....................... 35 – 66 15 1. Loans ............................................... 36 – 54 15 (a) Rescheduled loans .............................. 36 – 41 15 (b) Specific purpose loans for construction projects....................................... 42 – 45 16 (c) Specific purpose loans for the purchase of goods....................................... 46 – 52 17 (d) Specific purpose -

Shareholders

SHAREHOLDERS Arab Monetary Fund Abu Dhabi Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development Kuwait Banque d' Algerie Algiers Arab Banking Corporation (BSC) Manama Central Bank of Libya Tripoli Central Bank of Egypt (On behalf of Egyptian banks) Cairo Gulf International Bank Manama Arab Authority for Agricultural Investment and Development Khartoum The Arab Investment Company Riyadh Central Bank of Yemen Sana’a The Arab Investment & Export Credit Guarantee Corporation Kuwait Commercial Bank of Syria Damascus Banque Centrale de Tunisie Tunis Bank Almaghrib Rabat Libyan Foreign Bank Tripoli El Nilein Bank Khartoum Banque de L'Agriculture et du Development Rural Algiers Banque Nationale d'Algerie Algiers Banque Exterieure d'Algerie Algiers Credit Populaire d'Algerie Algiers Banque de Developpment Local Algiers Rasheed Bank Baghdad Rafidain Bank Baghdad Riyad Bank Riyadh Commercial Bank of Abu Dhabi (formerly Union National Bank) Abu Dhabi Arab International Bank Cairo Safwa Islamic Bank (and Partners) Amman Samba Financial Group Riyadh Tunis International Bank Tunis Arab Bank Limited Abu Dhabi National Commercial Bank Jeddah Al Ahli Bank of Kuwait KSC Kuwait Banque Marocaine du Commerce Exterieur Casablanca Commercial Bank of Kuwait Kuwait National Bank of Kuwait Kuwait Al Ahli United Bank Manama Arab African International Bank Cairo Banque Centrale Populaire Casablanca Emirates National Bank of Dubai Dubai Byblos Bank S.A.L. Beirut Credit Libanaise S.A.L. Beirut Arab Investment Bank Cairo Qatar National Bank Doha Bank of Beirut Beirut Fransabank Beirut Banque Audi Beirut Capital Bank of Jordan Amman Banque Libanese pour le Commerce Beirut Banque Libano-Francaise S.A.L. Beirut BLOM Bank S.A.L. -

Iraqi Sanctions, Notice 91-31

F e d e r a l R e s e r v e B a n k OF DALLAS ROBERT D. McTEER, JR. PRESIDENT April 8, 1991 AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER DALLAS, TEXAS 75222 Notice 91-31 TO: The Chief Executive Officer of each member bank and others concerned in the Eleventh Federal Reserve District SUBJECT Iraqi Sanctions DETAILS The Office of Foreign Assets Control finds that there is reasonable cause to believe that on or since the effective date of Executive Orders No. 12722 of August 2, 1990, and No. 12724 of August 9, 1990, the persons identi fied in Appendix A and Appendix B of this notice have been owned or controlled by or have acted or purported to act directly or indirectly on behalf of the Government of Iraq or the authorities thereof. The Office of Foreign Assets Control further finds that there is reasonable cause to believe that the vessels identified in Appendix B of this notice are Iraqi Government regis tered, owned or controlled property. Consequently, pursuant to section 575.306(d) of the Iraqi Sanctions Regulations (the "Regulations"), the persons described in Appendix A have been determined by the Office of Foreign Assets Control to be specially designated nationals of the Government of Iraq and, therefore, subject to the same prohibitions applicable to the Government of Iraq. Furthermore, the Office of Foreign Assets Control has determined that the vessels described in Appendix B are property in which there exists an interest of the Government of Iraq and are subject to blocking and to the same prohibitions applicable to the Government of Iraq. -

Honored, Not Contained the Future of Iraq’S Popular Mobilization Forces

MICHAEL KNIGHTS HAMDI MALIK AYMENN JAWAD AL-TAMIMI HONORED, NOT CONTAINED THE FUTURE OF IRAQ’S POPULAR MOBILIZATION FORCES HONORED, NOT CONTAINED THE FUTURE OF IRAQ’S POPULAR MOBILIZATION FORCES MICHAEL KNIGHTS, HAMDI MALIK, AND AYMENN JAWAD AL-TAMIMI THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY www.washingtoninstitute.org Policy Focus 163 First publication: March 2020 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2020 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1111 19th Street NW, Suite 500 Washington DC 20036 www.washingtoninstitute.org Cover photo: Reuters ii Contents LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS........................................................................................................... v PREFACE: KEY FINDINGS.......................................................................................................... vii PART I: THE LEGAL AUTHORITIES AND NOMINAL STRUCTURE OF THE HASHD............................................................................................................................................. xxi 1. Legal Basis of the Hashd ..................................................................................................... 1 2. Organizational Structure of the Hashd ........................................................................ -

El Iraqi 1950 Baghdad College, Baghdad, Iraq All Physical Materials Associated with the New England Province Archive Are Currently Held by the Jesuit Archives in St

New England Jesuit Archives are located at Jesuit Archives (St. Louis, MO) Digitized Collections hosted by CrossWorks. Baghdad College Yearbook 1950 El Iraqi 1950 Baghdad College, Baghdad, Iraq All physical materials associated with the New England Province Archive are currently held by the Jesuit Archives in St. Louis, MO. Any inquiries about these materials should be directed to the Jesuit Archives (http://jesuitarchives.org/). Electronic versions of some items and the descriptions and finding aids to the Archives, which are hosted in CrossWorks, are provided only as a courtesy. Digitized Record Information Baghdad College, Baghdad, Iraq, "El Iraqi 1950" (1950). Baghdad College Yearbook. 10. https://crossworks.holycross.edu/baghdadcoll/10 EL IRAQI 1950 BAGHDAD COLLEGE IRAQ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/eliraqi1950bagh EL IRAQI PUBLISHED BY THE SENIOR CLASS OF BAGHDAD COLLEGE IRAQ, NINETEEN HUNDRED AND FIFTY DEDIGATION Among the loyal friends of Baghdad College there are few who have observed the development of our school with greater devotion and enthusiasm than His Excellency, the Most Reverend Monsignor du Chayla. In the year 1939 he assumed the responsibilities of Latin Archbishop of Babylon and nine years later was appointed Apostolic Del- egate in Iraq. During the past decade his constant encour- agement and unflagging interest in the spiritual and intel- lectual advancement of Baghdad College students have been a source of inspiration to the administrators and faculty, as well as to the student body. His sincere generosity, the timely counsel he has offered, and his readiness to assist our various enterprises merit our warmest esteem and thankful remembrance. -

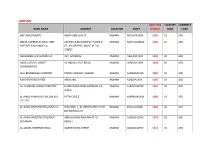

Jordan Bank Nbr Country Currency Bank Name Address Location Swift Dummy Code Code

JORDAN BANK NBR COUNTRY CURRENCY BANK NAME ADDRESS LOCATION SWIFT DUMMY CODE CODE ABC INVESTMENTS RANIA ABDULLA ST AMMAN ABCVJOA1XXX 1001 JO JOD ABDUL KAREEM AL-RAWI AND ALFAISLYA BUILDING 67, FLOOR 1: AMMAN RAWIJOAMXXX 1002 JO JOD PARTNER EXCHANGE CO 67, ALGARDENZ, WASFI AL TAL STREET ABUSHEIKHA EXCHANGE LLC 133, GARDENS AMMAN ABXLJOAAXXX 1003 JO JOD AGRICULTURAL CREDIT AL-ABDALI: SALT ROAD AMMAN ACRCJOA1XXX 1004 JO JOD CORPORATION AHLI BROKERAGE COMPANY PRINCE ZAID BIN: SHAKER AMMAN AHBOJOA1XXX 1005 JO JOD AJIAD FOR SECURITIES ABDOUN1 AMMAN AJSEJOA1XXX 1006 JO JOD AL ALAMI EXCHANGE COMPANY HADDAD BUILDING GARDENS: 51, AMMAN ALEYJOAMXXX 1007 JO JOD STREET AL AMAL FINANCIAL INVESMENTS FIFTH CIRCLE AMMAN AMFNJOA1XXX 1008 JO JOD CO. LTD AL ARABI INVESTMENT GROUP CO. BUILDING: 1, AL-RABIEH ABDULLAH AMMAN ATIGJOA1XXX 1009 JO JOD BIN RAWAHA ST. AL ARABI INVESTMENT GROUP ABDALLA BIN: RAWAHA ST AL AMMAN AIGMJOA1XXX 1010 JO JOD COMPANY RABIEH AL AWAEL INTERNATIONAL QUEEN RANIA STREET AMMAN AWAIJOA1XXX 1011 JO JOD BANK NBR COUNTRY CURRENCY BANK NAME ADDRESS LOCATION SWIFT DUMMY CODE CODE AL FARES FOR FINANCIAL INVEST CO AMMAN STREET IRBID FRRSJOA1XXX 1012 JO JOD AL MAWARED FOR BROKERAGE ISSAM AL AMMAN MBRCJOA1XXX 1013 JO JOD COMPANY AL RAJHI BANK, JORDAN BRANCH 999, JABAL AMMAN AMMAN RJHIJOAMXXX 1014 JO JOD AL WAMEEDH FOR FINANCIAL UM AMMAN WFSIJOA1XXX 1015 JO JOD SERVICES AND INVESTMENT AL-AULA FINANCIAL INVESTMENTS NOUR ST AMMAN ALNTJOA1XXX 1016 JO JOD ALAWNEH EXCHANGE L.L.C 15, ABDULHAMID SHOMAN STR AMMAN ALELJOAMXXX 1017 JO JOD AL-BILAD FOR -

BANKS in the ARAB COUNTRIES Mashreq Bank Citibank Mashreq Bank Unicorn Investment Bank M

AL BAYAN BUSINESS GUIDE BANKS & INVESTMENT COMPANIES IN THE ARAB COUNTRIES Central Bank Jammal Trust Bank Dr. Farouk Al Oukda M. Nabil Kamal Al Hakem Tel:3931514 - Fax:3926211 Tel: 7948260-7957365 - Fax: 7957651 www.cbe.org.eg www.jammalbank.com.lb BANKS IN THE ARAB COUNTRIES Mashreq Bank CitiBank Mashreq Bank Unicorn Investment Bank M. Michel Akkad Tel: 5710419 - Fax: 5710423 Rayan Algerian Bank Bahrain & Kuwait Commercial Bank of Bahrain www.mashreqbank.com Tel: 7951874 - Fax: 7957743 ALGERIA M. Madjid Nassou M. Kaled Chahine M. Mohammad El Zamel Tel:17 210114- Fax:17 213516 -Box: 20654 Tel:17 566000 - Fax: 17 566001 Misr www.citibank.com/egypt Agriculture & Devel Rural Tel:21 449900 - Fax:21 449194 Tel:17 223388-Fax:17 229822-Box: 597 Tel:17 220199-Fax:17 224482-Box: 793 Melli Iran www.unicorninvestmentbank.com M. Mohammad Barakat Commerce & Development M. Farouk Bouyacoub www.alrayan - bank.com www.bbkonline.com www.cbbonline.com Tel:17 229910-Fax:17 224402-Box: 785 United Bank Tel: 3910656 - Fax: 3906555 M. Fathi Yassin Ali Tel:21 634459 - Fax:21 635746 Trust Bank Algeria Commerzbank E-mail: [email protected] Tel:17 224030-Fax:17 224099-Box: 546 www.banquemisr.com.eg Bahrain Development Bank Tel: 3475584 - Fax: 3023963 Algeria Gulf Bank M. George Abou Jaoudeh Tel:17 531431- Fax:17 531435- Box: 11800 Merril Lynch United Gulf Bank Misr International M. Nidal Oujan www.bcdcairo.com M. William Khouri Tel:21 549755 - Fax:21 549750 E-mail: [email protected] Tel:17 530260-Fax:17 530245-Box: 10399 M. -

Décrets, Arrêtés, Circulaires

19 juin 2020 JOURNAL OFFICIEL DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE Texte 12 sur 145 Décrets, arrêtés, circulaires TEXTES GÉNÉRAUX MINISTÈRE DE L’ÉCONOMIE ET DES FINANCES Arrêté du 16 juin 2020 portant application des articles L. 562-3, L. 745-13, L. 755-13 et L. 765-13 du code monétaire et financier NOR : ECOT2013938A Par arrêté du ministre de l’économie et des finances en date du 16 juin 2020, vu la décision 2013/184/PESC du Conseil du 22 avril 2013 concernant les mesures restrictives à l’encontre du Myanmar/de la Birmanie, modifiée notamment par la décision (PESC) 2020/563 du 23 avril 2020 ; vu le code monétaire et financier, notamment ses articles L. 562-3, L. 745-13, L. 755-13 et L. 765-13, l’arrêté du 20 décembre 2019 (NOR : ECOT1936811) est abrogé. A Saint-Barthélemy, Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, en Nouvelle-Calédonie, en Polynésie française, dans les îles Wallis et Futuna et dans les Terres australes et antarctiques françaises, les fonds et ressources économiques qui appartiennent à, sont possédés, détenus ou contrôlés par les personnes mentionnées dans l’annexe sont gelés. Le présent arrêté entre en vigueur à la date de sa publication au Journal officiel de la République française pour une durée de six mois. Notification des voies et délais de recours Le présent arrêté peut être contesté dans les deux mois à compter de sa notification, soit par recours gracieux adressé au ministère de l’économie et des finances au 139, rue de Bercy, 75572 Paris Cedex 12, télédoc 233, ou à [email protected], soit par recours contentieux auprès du tribunal administratif de Paris, 7, rue de Jouy, 75181 Paris Cedex 04, téléphone : 01-44-59-44-00, télécopie : 01-44-59-46-46, urgences télécopie référés : 01-44-59-44-99, [email protected]. -

USAID-Funded Economic Governance II Project Assessment of Iraqi

USAID-Funded Economic Governance II Project Assessment of Iraqi State-Owned Banks 15 NOVEMBER 2005 USAID-Funded Economic Governance II Project Assessment of Iraqi State-Owned Banks 15 November 2005 The USAID-Funded Economic Governance II program is pleased to present this report entitled Assessment of Iraqi State-Owned Banks. The report provides the findings of a team of commercial bank restructuring experts assigned to six of the seven Iraqi state-owned institutions. This document contains analyses based on employee-provided data. Given significant weaknesses in the operational and finance functions, the validity of financial indicators remains in question. As well, given the ongoing security concerns in Iraq, the advisory team’s onsite presence was significantly impacted. Under such limitations, the ability to conduct an in-depth review of each banking department was not possible. The purpose of this assessment was to determine the financial condition of the institutions in light of the emergence of a new Iraqi financial system. Efforts have been in place since summer 2004 to identify a strategic approach to the state-owned banking dilemma in Iraq, focusing on possible options to be conducted by the new Government of Iraq (GoI). As a critical foundation of economic reform, it was determined that a baseline assessment must be conducted in order to provide the necessary data to the GoI. As experienced throughout the emerging markets, a key component of economic reform is a well-regulated, vibrant banking system that can not only provide credit to the emerging private sector but to do so in a transparent manner. -

Central Bank of Jordan

CENTRAL BANK OF JORDAN FIFTY THIRD ANNUAL REPORT 2016 RESEARCH DEPARTMENT Deposit No. at the National Library of Jordan 707 / 3 / 2002 Issued in September 2017 Central Bank of Jordan Press OUR VISION To be one of the most capable central banks regionally and internationally in maintaining monetary stability and ensuring the soundness of the financial system thereby contributing to sustained economic growth in the Kingdom. OUR MISSION Ensuring monetary and financial stability by maintaining price stability, protecting the value of the Jordanian Dinar and through an interest rate structure consistent with the level of economic activity thereby contributing toward an attractive investment environment and a sound macroeconomic environment. Furthermore, the Central Bank of Jordan strives to ensure the safety and soundness of the banking system and the resilience of the national payments system. To this end, the Central Bank of Jordan adopts and implements effective monetary and financial policies and employs its human, technological, and financial resources in an optimal manner in order to effectively achieve its objectives. OUR VALUES Loyalty : Commitment and dedication to the institution, its staff and clients. Integrity : Seeking to achieve our organizational goals honestly and objectively. Excellence : Seeking to continuously improve our performance and deliver our services in accordance with international standards. Continuous Learning : Aspiring to continuously improve practical and academic skills to maintain a level of excellence in accordance with international best practices. Teamwork : Working together, on all levels of management, to achieve our national and organizational goals with a collective spirit of commitment. Transparency : Dissemination of information and knowledge, and the simplification of procedures and regulations in a comprehensible and professional manner.