The Business and Pleasure of Filmic Lesbians Performing Onstage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

" We Are Family?": the Struggle for Same-Sex Spousal Recognition In

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fmrn any type of computer printer, The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reprodudion. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e-g., maps, drawings, &arb) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to tight in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and Mite photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustratims appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell 8 Howell Information and Leaning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 "WE ARE FAMILY'?": THE STRUGGLE FOR SAME-SEX SPOUSAL RECOGNITION IN ONTARIO AND THE CONUNDRUM OF "FAMILY" lMichelIe Kelly Owen A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto Copyright by Michelle Kelly Owen 1999 National Library Bibliothiique nationale l*B of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services sewices bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. -

Felix Issue 0985, 1994

loo<tF The Student Newspaper of Imperiaiperiall ColleqCollegee I 3DRI8B3iaCE||olrj g 210CT94 TCCB-tSCTIONj enamings benefits of the proposal had not. ANDREW DORMAN-SMITH been adequately debated. Professor Shaw said the name of Senior academics at. the. the Department itself does not Department, of Mineral Resources overly matter, and said he was, Engineering (MRE) have called "a believer in tradition". Professor for further discussions over a plan Shaw would not say if he sup- to rename the department. Earth ported the name change proposal. Resources Engineering has However, the new head of emerged as the favourite choice MRE, and Dean of the newly for a new name, after discussions established Graduate School of between college officials. the Environment, Professor The change has been mooted Woods, is believed to think the following a letter from the proposal is a 'great idea'. His role Professor John Archer, Pro- as Dean will be to coordinate the Rector, which asks for comments departments of Imperial, and to on the new title. Professor Archer, present the benefits for research said that he has received only one of the college in line with a review negative response to his letter, completed in May by Sir John and claimed that most of the Mason. department's staff agree with the The other two RSM depart- proposal. But Professor Archer ments may also change names. said discussions are continuing - The college's chief decision mak- despite the publication of an offi- ing body, the Management cial college note which says the Finnish Embassy Planning Group (MPG), has sug- Photo by Ivan Chan change will take place "shortly". -

Beverly Hills

briefs • City to subsidize $1.6 million briefs • City refuses to declare rudy cole • My recommendations loan for City Manager housing Page 3 opinion on subway route Page 4 for state office Page 6 ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES Issue 575 • October 7 - October 13, 2010 OUR 11th Beverly Hills’ Anniversary First Lady The Weekly’s interview with Lonnie Delshad cover story • pages 8-9 Few motorists would risk their lives by for anyone but a Democrat because it would briefs • Lively subway route hearing at briefs • Julian Gold announces rudy cole • Roxbury Park Page 2 candidacy for City Council Page 3 United city speaks Page 6 bicycle community in the region, and isn’t have disappointed his liberal mother. As ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com that part of our transportation problem? Too one of my favorite commentators, Dennis letters too few folks using alternate transportation Prager, pointed out in a recent article, so WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES means too many cars on the road. Bike- many registered Democrats vote for Left- Issue 574 • September 30 - October 6, 2010 friendly infrastructure not only protects wing candidates who do not share their Beverly High Athletic cyclists entitled to ride all of the streets in views for purely emotional, nonsensical Alumni to be inducted & email our city, but it reduces motorist liability too. reasons. In Rudy’s case, it is because his Simply put, bikes belong, so let’s plan for mother would disapprove of him voting into Hall of Fame them to accommodate bikes safely. -

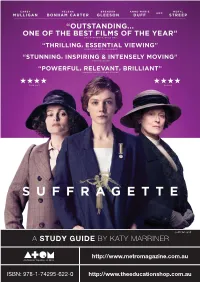

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

Makers: Women in Hollywood

WOMEN IN HOLLYWOOD OVERVIEW: MAKERS: Women In Hollywood showcases the women of showbiz, from the earliest pioneers to present-day power players, as they influence the creation of one of the country’s biggest commodities: entertainment. In the silent movie era of Hollywood, women wrote, directed and produced, plus there were over twenty independent film companies run by women. That changed when Hollywood became a profitable industry. The absence of women behind the camera affected the women who appeared in front of the lens. Because men controlled the content, they created female characters based on classic archetypes: the good girl and the fallen woman, the virgin and the whore. The women’s movement helped loosen some barriers in Hollywood. A few women, like 20th century Fox President Sherry Lansing, were able to rise to the top. Especially in television, where the financial stakes were lower and advertisers eager to court female viewers, strong female characters began to emerge. Premium cable channels like HBO and Showtime allowed edgy shows like Sex in the City and Girls , which dealt frankly with sex from a woman’s perspective, to thrive. One way women were able to gain clout was to use their stardom to become producers, like Jane Fonda, who had a breakout hit when she produced 9 to 5 . But despite the fact that 9 to 5 was a smash hit that appealed to broad audiences, it was still viewed as a “chick flick”. In Hollywood, movies like Bridesmaids and The Hunger Games , with strong female characters at their center and strong women behind the scenes, have indisputably proven that women centered content can be big at the box office. -

2009 Program Book

CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN GHALLL OHF FAFME 2009 City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Richard M. Daley Dana V. Starks Mayor Chairman and Commissioner Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues William W. Greaves, Ph.D. Director/Community Liaison COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION ARE AVAILABLE UPON REQUEST City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues 740 North Sedgwick Street, Suite 300 Chicago, Illinois 60654-3478 312.744.7911 (VOICE) 312.744.1088 (CTT/TDD) © 2009 Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame In Memoriam Robert Maddox Tony Midnite 2 3 4 CHICAGO GAY AND LESBIAN HALL OF FAME The Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame is both a historic event and an exhibit. Through the Hall of Fame, residents of Chicago and the world are made aware of the contributions of Chicago’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities and the communities’ efforts to eradicate bias and discrimination. With the support of the City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations, the Advisory Council on Gay and Lesbian Issues (now the Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Issues) established the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in June 1991. The inaugural induction ceremony took place during Pride Week at City Hall, hosted by Mayor Richard M. Daley. This was the first event of its kind in the country. The Hall of Fame recognizes the volunteer and professional achievements of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals, their organizations and their friends, as well as their contributions to the LGBT communities and to the city of Chicago. -

Chapter Six: Activist Agendas and Visions After Stonewall (1969-1973)

Chapter Six: Activist Agendas and Visions after Stonewall (1969-1973) Documents 103-108: Gay Liberation Manifestos, 1969-1970 The documents reprinted in The Stonewall Riots are “Gay Revolution Comes Out,” Rat, 12 Aug. 1969, 7; North American Conference of Homophile Organizations Committee on Youth, “A Radical Manifesto—The Homophile Movement Must Be Radicalized!” 28 Aug. 1969, reprinted in Stephen Donaldson, “Student Homophile League News,” Gay Power (1.2), c. Sep. 1969, 16, 19-20; Preamble, Gay Activists Alliance Constitution, 21 Dec. 1969, Gay Activists Alliance Records, Box 18, Folder 2, New York Public Library; Carl Wittman, “Refugees from Amerika: A Gay Manifesto,” San Francisco Free Press, 22 Dec. 1969, 3-5; Martha Shelley, “Gay is Good,” Rat, 24 Feb. 1970, 11; Steve Kuromiya, “Come Out, Wherever You Are! Come Out,” Philadelphia Free Press, 27 July 1970, 6-7. For related early sources on gay liberation agendas and philosophies in New York, see “Come Out for Freedom,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 1; Bob Fontanella, “Sexuality and the American Male,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 15; Lois Hart, “Community Center,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 15; Leo Louis Martello, “A Positive Image for the Homosexual,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 16; “An Interview with New York City Liberationists,” San Francisco Free Press, 7 Dec. 1969, 5; Bob Martin, “Radicalism and Homosexuality,” Come Out!, 10 Jan. 1970, 4; Allan Warshawsky and Ellen Bedoz, “G.L.F. and the Movement,” Come Out!,” 10 Jan. 1970, 4-5; Red Butterfly, “Red Butterfly,” Come Out!, 10 Jan. 1970, 4-5; Bob Kohler, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” Come Out!, 10 Jan. -

Visualizing Levinas:Existence and Existents Through Mulholland Drive

VISUALIZING LEVINAS: EXISTENCE AND EXISTENTS THROUGH MULHOLLAND DRIVE, MEMENTO, AND VANILLA SKY Holly Lynn Baumgartner A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2005 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Kris Blair Don Callen Edward Danziger Graduate Faculty Representative Erin Labbie ii © 2005 Holly Lynn Baumgartner All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor This dissertation engages in an intentional analysis of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas’s book Existence and Existents through the reading of three films: Memento (2001), Vanilla Sky (2001), and Mulholland Drive, (2001). The “modes” and other events of being that Levinas associates with the process of consciousness in Existence and Existents, such as fatigue, light, hypostasis, position, sleep, and time, are examined here. Additionally, the most contested spaces in the films, described as a “Waking Dream,” is set into play with Levinas’s work/ The magnification of certain points of entry into Levinas’s philosophy opened up new pathways for thinking about method itself. Philosophically, this dissertation considers the question of how we become subjects, existents who have taken up Existence, and how that process might be revealed in film/ Additionally, the importance of Existence and Existents both on its own merit and to Levinas’s body of work as a whole, especially to his ethical project is underscored. A second set of entry points are explored in the conclusion of this dissertation, in particular how film functions in relation to philosophy, specifically that of Levinas. What kind of critical stance toward film would be an ethical one? Does the very materiality of film, its fracturing of narrative, time, and space, provide an embodied formulation of some of the basic tenets of Levinas’s thinking? Does it create its own philosophy through its format? And finally, analyzing the results of the project yielded far more complicated and unsettling questions than they answered. -

ANGEL DEANGELIS Hair Stylist IATSE 798

ANGEL DEANGELIS Hair Stylist IATSE 798 FILM HUSTLERS Department Head Director: Lorene Scafaria PRIVATE LIFE Department Head Director: Tamara Jenkins SHOW DOGS Department Head – Las Vegas Shoot Director: Raja Gosnell COLLATERAL BEAUTY Department Head Director: David Frankel Cast: Helen Mirren, Ed Norton, Keira Knightley THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2 Department Head Director: Marc Webb Cast: Dane DeHaan THE HEAT Department Head Director: Paul Feig Cast: Melissa McCarthy MUHAMMAD ALI’S GREATEST FIGHT Department Head Director: Stephen Frears Cast: Christopher Plummer, Benjamin Walker, Frank Langella JACK REACHER Department Head Director: Christopher McQuarrie Cast: Rosamund Pike, Robert Duvall, Richard Jenkins, Werner Herzog, Jai Courtney, Joseph Sikora, GODS BEHAVING BADLY Department Head Director: Marc Turtletaub Cast: Alicia Silverstone, Edie Falco, Ebon Moss-Bachrach, Oliver Platt, Christopher Walken, Rosie Perez, Phylicia Rashad THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN Key Hair (New York) Director: Marc Webb Cast: Embeth Davidtz NEW YEAR’S EVE Department Head Director: Garry Marshall Cast: Jessica Biel, Zac Efron, Cary Elwes, Alyssa Milano, Carla Gugino, Jon Bon Jovi, Sofia Vergara, Lea Michele, James Belushi, Abigail Breslin, Josh Duhamel, Cherry Jones, THE MILTON AGENCY 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Angel DeAngelis Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 Hair [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 5 THE SITTER Department Head Director: David Gordon Green Cast: Jonah Hill, Ari Graynor PREMIUM RUSH Department Head -

Sxsw Film Festival Announces 2018 Features and Opening Night Film a Quiet Place

SXSW FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES 2018 FEATURES AND OPENING NIGHT FILM A QUIET PLACE Film Festival Celebrates 25th Edition Austin, Texas, January 31, 2018 – The South by Southwest® (SXSW®) Conference and Festivals announced the features lineup and opening night film for the 25th edition of the Film Festival, running March 9-18, 2018 in Austin, Texas. The acclaimed program draws thousands of fans, filmmakers, press, and industry leaders every year to immerse themselves in the most innovative, smart and entertaining new films of the year. During the nine days of SXSW 132 features will be shown, with additional titles yet to be announced. The full lineup will include 44 films from first-time filmmakers, 86 World Premieres, 11 North American Premieres and 5 U.S. Premieres. These films were selected from 2,458 feature-length film submissions, with a total of 8,160 films submitted this year. “2018 marks the 25th edition of the SXSW Film Festival and my tenth year at the helm. As we look back on the body of work of talent discovered, careers launched and wonderful films we’ve enjoyed, we couldn’t be more excited about the future,” said Janet Pierson, Director of Film. “This year’s slate, while peppered with works from many of our alumni, remains focused on new voices, new directors and a range of films that entertain and enlighten.” “We are particularly pleased to present John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place as our Opening Night Film,” Pierson added.“Not only do we love its originality, suspense and amazing cast, we love seeing artists stretch and explore. -

Biographies of the Contributors Norma Alarcon Born in Monclova, Coahuila, Mexico and Raised in Chicago

246 Biographies of the Contributors Norma Alarcon Born in Monclova, Coahuila, Mexico and raised in Chicago. Will receive Ph.D. in Hispanic Literatures in 1981 from Indiana University where she is presently employed as Visiting Lecturer in Chicano- Riqueno Studies. Gloria Evangelina Anzaldtia I'm a Tejana Chicana poet, hija de Amalia, Hecate y Yemaya. I am a Libra (Virgo cusp) with VI – The Lovers destiny. One day I will walk through walls, grow wings and fly, but for now I want to play Hermit and write my novel, Andrea. In my spare time I teach, read the Tarot, and doodle in my journal. Barbara M. Cameron Lakota patriot, Hunkpapa, politically non-promiscuous, born with a caul. Will not forget Buffalo Manhattan Hat and Mani. Love Marti, Maxine, Leonie and my family. Still beading a belt for Pat. In love with Robin. Will someday raise chickens in New Mexico. Andrea R. Canaan Born in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1950. Black woman, mother and daughter. Director of Women And Employment which develops and places women on non-traditional jobs. Therapist and counselor to bat- tered women, rape victims, and families in stress. Poetry is major writing expression. Speaker, reader, and community organizer. Black feminist writer. Jo Carrillo Died and born 6000 feet above the sea in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Have never left; will never leave. But for now, I'm living in San Fran- cisco. I'm loving and believing in the land, my extended family (which includes Angie, Mame and B. B. Yawn) and my sisters. Would never consider owning a souvenir chunk of uranium. -

Queer Tastes: an Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature Jacqueline Kristine Lawrence University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature Jacqueline Kristine Lawrence University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, Jacqueline Kristine, "Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 1021. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1021 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Jacqueline Kristine Lawrence University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in English, 2010 May 2014 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _________________________ Dr. Lisa Hinrichsen Thesis Director _________________________ _________________________ Dr. Susan Marren Dr. Robert Cochran Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT Southern identities are undoubtedly influenced by the region’s foodways. However, the South tends to neglect and even to negate certain peoples and their identities. Women, especially lesbians, are often silenced within southern literature. Where Tennessee Williams and James Baldwin used literature to bridge gaps between gay men and the South, southern lesbian literature severely lacks a traceable history of such connections.