Quantum of Solace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Damsel Dark Money the Darkest Minds the Dawn

DAMSEL Actors: Robert Pattinson. Robert Forster. Actresses: Mia Wasikowska. DARK MONEY THE DARKEST MINDS Actors: Bradley Whitford. Harris Dickinson. Patrick Gibson. Skylan Brooks. Wade Williams. Mark O'Brien. Wallace Langham. Sammi Rotibi. McCarrie McCausland. Logan Siu. Actresses: Amandla Stenberg. Mandy Moore. Miya Cech. Gwendoline Christie. Golden Brooks. Lidya Jewett. Faye Foley. Deja Dee. Cynne Simpson. Tara Jones. THE DAWN WALL DEADPOOL 2 Actors: Ryan Reynolds. Josh Brolin. Julian Dennison. T. J. Miller. Karan Soni. Jack Kesy. Eddie Marsan. Stefan Kapicic. Randal Reeder. Nikolai Witschl. Actresses: Morena Baccarin. Zazie Beetz. Leslie Uggams. Brianna Hildebrand. Shioli Kutsuna. Hayley Sales. Islie Hirvonen. Tanis Dolman. Eleanor Walker. Sonia Sunger. DEAR MOLLY Actors: Alok Rajwade. Björn Johansson. Jaswinder Singh. Tomas Johansson. Vilas Mane. Jan- Erik Tholin. Actresses: Chitrika Jadhav. Gurbani Gill. Ashwini Giri. Sanjita Shroff. Mrinmayee Godbole. Urvi Yadav. Alicia Borggren. Lia Boysen. THE DEATH OF STALIN Actors: Steve Buscemi. Michael Palin. Jeffrey Tambor. Simon Russell Beale. Rupert Friend. Jason Isaacs. Actresses: Andrea Riseborough. Olga Kurylenko. DEATH WISH Actors: Bruce Willis. Vincent D'Onofrio. Dean Norris. Actresses: Camila Morrone. Elisabeth Shue. Kimberly Elise. DELAWARE SHORE Actors: James Robinson, Jr.. Jason R. Maga. Kevin Austra. Ed Aristone. Kevin Francis. Kevin D. Benton. Charles "Linwood" Jackson. Actresses: Gail Wagner. Emily McKinley Hill. Kirsten Valania. Sharyn Pak Withers. Brittany Anne Williamson. Bella Dontine. Jessica Classen. DEN OF THIEVES Actors: Gerard Butler. Pablo Schreiber. O'Shea Jackson, Jr.. Curtis "50 Cent" Jackson. Maurice Compte. Brian Van Holt. Evan Jones. Mo McRae. Kaiwi Lyman. Eric Braeden. Actresses: Meadow Williams. Dawn Olivieri. Charline St. Charles. Tracey Bonner. Alexus Lapri Geier. Sonya Chung. -

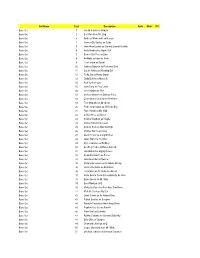

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Widescreen Weekend 2007 Brochure

The Widescreen Weekend welcomes all those fans of large format and widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and Imax – and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the best of cinema. HOW THE WEST WAS WON NEW TODD-AO PRINT MAYERLING (70mm) BLACK TIGHTS (70mm) Saturday 17 March THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR Monday 19 March Sunday 18 March Pictureville Cinema Pictureville Cinema FLYING MACHINES Pictureville Cinema Dir. Terence Young France 1960 130 mins (PG) Dirs. Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall USA 1962 Dir. Terence Young France/GB 1968 140 mins (PG) Zizi Jeanmaire, Cyd Charisse, Roland Petit, Moira Shearer, 162 mins (U) or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes Omar Sharif, Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, Ava Gardner, Maurice Chevalier Debbie Reynolds, Henry Fonda, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, (70mm) James Robertson Justice, Geneviève Page Carroll Baker, John Wayne, Richard Widmark, George Peppard Sunday 18 March A very rare screening of this 70mm title from 1960. Before Pictureville Cinema It is the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The world is going on to direct Bond films (see our UK premiere of the There are westerns and then there are WESTERNS. How the Dir. Ken Annakin GB 1965 133 mins (U) changing, and Archduke Rudolph (Sharif), the young son of new digital print of From Russia with Love), Terence Young West was Won is something very special on the deep curved Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, James Fox, Alberto Sordi, Robert Emperor Franz-Josef (Mason) finds himself desperately looking delivered this French ballet film. -

Download March 2007 Movie Schedule

Movie Museum MARCH 2007 COMING ATTRACTIONS THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY STRANGER THAN CHOCOLAT THE CAVE OF THE STRANGER THAN THE CAVE OF THE FICTION (1988-French/German/ YELLOW DOG FICTION YELLOW DOG (2006) Cameroon) (2005-Mongolia/Germany) (2006) (2005-Mongolia/Germany) in widescreen in French with English in Mongolian with English in widescreen in Mongolian with English with Will Ferrell, Maggie subtitles & in widescreen subtitles & in widescreen with Will Ferrell, Maggie subtitles & in widescreen Gyllenhaal, Dustin Hoffman, with Isaach de Bankolé, Giulia with Babbayar Batchuluun, Gyllenhaal, Dustin Hoffman, Emma Thompson. with Babbayar Batchuluun, Boschi, François Cluzet. Nansal Batchuluun. Emma Thompson. Nansal Batchuluun. Written and Directed by Directed by Directed by Written and Directed by Marc Forster. Directed and Co-written by Byambasuren Davaa. Marc Forster. Byambasuren Davaa. Claire Denis. 12:30, 3, 5:30 & 8pm 1 2, 4, 6, 8pm 2 2, 4, 6 & 8pm 34 12:30, 3, 5:30 & 8pm 2, 4 & 6pm ONLY 5 ENLIGHTENMENT Hawaii Premeiere! MacARTHUR'S Hawaii Premeiere! BORAT: Cultural GUARANTEED MY COUNTRY, CHILDREN MY COUNTRY, Learnings of America for (2000-Germany) MY COUNTRY (1985-Japan) MY COUNTRY Make Benefit Glorious in German with English (2006) In Japanese with (2006) Nation of Kazakhstan subtitles & in widescreen in Arabic/English/Kurdish English subtitles in Arabic/English/Kurdish (2006) with Uwe Ochsenknecht, with English subtitles with Masako Natsume, Shima with English subtitles in widescreen Gustav-Peter Wöhler. & in widescreen Iwashita, Hiromi Go, & in widescreen with Sacha Baron Cohen, Riveting documentary Ken Watanabe. Riveting documentary Ken Davitian, Luenell. Directed and Co-written by concerning the Iraqi election. -

International Casting Directors Network Index

International Casting Directors Network Index 01 Welcome 02 About the ICDN 04 Index of Profiles 06 Profiles of Casting Directors 76 About European Film Promotion 78 Imprint 79 ICDN Membership Application form Gut instinct and hours of research “A great film can feel a lot like a fantastic dinner party. Actors mingle and clash in the best possible lighting, and conversation is fraught with wit and emotion. The director usually gets the bulk of the credit. But before he or she can play the consummate host, someone must carefully select the right guests, send out the invites, and keep track of the RSVPs”. ‘OSCARS: The Role Of Casting Director’ by Monica Corcoran Harel, The Deadline Team, December 6, 2012 Playing one of the key roles in creating that successful “dinner” is the Casting Director, but someone who is often over-looked in the recognition department. Everyone sees the actor at work, but very few people see the hours of research, the intrinsic skills, the gut instinct that the Casting Director puts into finding just the right person for just the right role. It’s a mix of routine and inspiration which brings the characters we come to love, and sometimes to hate, to the big screen. The Casting Director’s delicate work as liaison between director, actors, their agent/manager and the studio/network figures prominently in decisions which can make or break a project. It’s a job that can't garner an Oscar, but its mighty importance is always felt behind the scenes. In July 2013, the Academy of Motion Pictures of Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) created a new branch for Casting Directors, and we are thrilled that a number of members of the International Casting Directors Network are amongst the first Casting Directors invited into the Academy. -

The James Bond Quiz Eye Spy...Which Bond? 1

THE JAMES BOND QUIZ EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 1. 3. 2. 4. EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 5. 6. WHO’S WHO? 1. Who plays Kara Milovy in The Living Daylights? 2. Who makes his final appearance as M in Moonraker? 3. Which Bond character has diamonds embedded in his face? 4. In For Your Eyes Only, which recurring character does not appear for the first time in the series? 5. Who plays Solitaire in Live And Let Die? 6. Which character is painted gold in Goldfinger? 7. In Casino Royale, who is Solange married to? 8. In Skyfall, which character is told to “Think on your sins”? 9. Who plays Q in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service? 10. Name the character who is the head of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Service in You Only Live Twice? EMOJI FILM TITLES 1. 6. 2. 7. ∞ 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. GUESS THE LOCATION 1. Who works here in Spectre? 3. Who lives on this island? 2. Which country is this lake in, as seen in Quantum Of Solace? 4. Patrice dies here in Skyfall. Name the city. GUESS THE LOCATION 5. Which iconic landmark is this? 7. Which country is this volcano situated in? 6. Where is James Bond’s family home? GUESS THE LOCATION 10. In which European country was this iconic 8. Bond and Anya first meet here, but which country is it? scene filmed? 9. In GoldenEye, Bond and Xenia Onatopp race their cars on the way to where? GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. In which Bond film did the iconic Aston Martin DB5 first appear? 2. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

F I L M S E R I E S The Immigrant Experience in English ASSOCIACIÓ DE PROFESSORS DEPARTAMENT D’ANGLÈS D’ANGLÈS DE LES ILLES BALEARS DE L’EOI DE PALMA APABAL and the Department of English of the Palma EOI are pleased to present four films with immigration - related themes during the January 2013 time frame. WHEN Wednesday, 9 January 2013 Wednesday, 16 January 2013 Wednesday, 23 January 2013 Wednesday, 30 January 2013 WHAT TIME 18.00 h. WHERE “Sa Nostra Cultural Centre”, c/ Concepció 12. Tel. 971 72 52 10 The films will be in the original English, with subtitles. * Attendance is free. Coordinator: Assumpta Sureda Film Moderators: Carol Williams, Michael Carroll, James Miele and Armando Fernández. More Information: www.apabal.com [email protected] January 9 (Wednesday) 18.00 h. THE TERMINAL (2004) An eastern immigrant finds himself stranded in JFK airport, and must take up temporary residence there. Director: Steven Spielberg Writers: Andrew Niccol (story), Sacha Gervasi (story). Stars: Tom Hanks, Catherine Zeta-Jones and Chi McBride. FILM MODERATOR: Carol Willliams January 16 (Wednesday) 18.00 h BEND IT LIKE BECKHAM (2002) The daughter of orthodox Sikh rebels against her parents' traditionalism by running off to Germany with a football team (soccer in America). Director: Gurinder Chadha. Writers:, Gurinder Chadha, Guljit Bindra. Stars: Parminder Nagra, Kheira Knightley and Jonathan RyesMeyers. FILM MODERATOR: Michael Carroll January 23 (Wednesday) 18.00 h MY BEAUTIFUL LAUNDERETTE (1985) Only recommended to people over 16. An ambitious Asian Briton and his white lover strive for success and hope, when they open up a glamorous laundromat. -

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

A Queer Analysis of the James Bond Canon

MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2019 Copyright 2019 by Grant C. Hester ii MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester This dissertation was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Jane Caputi, Center for Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Communication, and Multimedia and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Khaled Sobhan, Ph.D. Interim Dean, Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Jane Caputi for guiding me through this process. She was truly there from this paper’s incubation as it was in her Sex, Violence, and Hollywood class where the idea that James Bond could be repressing his homosexuality first revealed itself to me. She encouraged the exploration and was an unbelievable sounding board every step to fruition. Stephen Charbonneau has also been an invaluable resource. Frankly, he changed the way I look at film. His door has always been open and he has given honest feedback and good advice. Oliver Buckton possesses a knowledge of James Bond that is unparalleled. I marvel at how he retains such information. -

Quantum of Solace De Marc Forster Pierre Barrette

Document generated on 09/28/2021 5:22 p.m. 24 images Quantum of Solace de Marc Forster Pierre Barrette Comédie Number 140, December 2008, January 2009 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/25257ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Barrette, P. (2008). Review of [Quantum of Solace de Marc Forster]. 24 images, (140), 60–60. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ W. d'Oliver Stone figure paternelle, George juxtaposition d'événements réels soigneuse Jr est donc en quête per ment choisis suffisant à en déterminer une pétuelle d'une reconnais interprétation univoque. Quant au reste, sance qui, à ses yeux, ne Stone se fait portraitiste et livre son verdict viendra jamais. sur l'entourage de ce président faiblard : Dick Pour faire ce portrait, W. Cheney est la sombre eminence grise qui télé raconte essentiellement guide les décisions, Karl Rove une immonde la deuxième moitié du créature rampante, Condoleeza Rice une premier mandat du pré bourgeoise dédaigneuse, Donald Rumsfeld sident, c'est-à-dire que un dangereux imbécile, Paul Wolfowitz une Stone se concentre sur les quantité négligeable et Colin Powell la seule événements entourant la personne sensée au milieu de cette poignée 1/1/ peut être vu comme un double de décision d'envahir l'Irak, truffant son récit d'illuminés. -

Implications of Obama's Second Term Analyzed Panel Explores

THE INDEPENDENT TO UNCOVER NEWSPAPER SERVING THE TRUTH NOTRE DAME AND AND REPORT SAINT Mary’s IT ACCURATELY VOLUME 46, ISSUE 52 | FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 9, 2012 | NDSMCOBSERVER.COM ELECTION 2012 Implications of Obama’s second term analyzed Experts provide Students react to insight on next election results four years with mixed feelings By KRISTEN DURBIN By ANNA BOARINI News Editor News Writer In the next four years of his Much like the rest of the presidency, Barack Obama country, the reactions of will expand on the efforts of Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s his first term in office. But he students to the outcome of wouldn’t have had the oppor- the 2012 presidential elec- tunity to do so without a broad tion spanned the political national base of support. spectrum. In terms of the immediate For Saint Mary’s senior Liz results of the election, politi- Craney, President Barack cal science professor Darren Obama’s reelection was a Davis said Obama’s mainte- positive outcome. nance of his 2008 electorate “The issues that mean the contributed to his reelection. KEVIN SONG | The Observer most to me, my views line President Barack Obama delivers his victory speech in Chicago on Tuesday night after winning a second see ELECTION PAGE 6 term in the White House. Obama said he plans to emphasize bipartisanship in Washington. see REACTION PAGE 7 Panel explores coeducation at Notre Dame By NICOLE MICHELS went down and then reality hit.” possibly assimilate women,” News Writer Sterling spoke at the Eck Hesburgh said. “I’m just delight- Visitor Center Thursday in a ed that we are a better university, “It was like running a gauntlet, panel discussion titled “Paving better Catholic university, better every single day.” the Way: Reflections on the Early modern university because we Jeanine Sterling, a 1976 alum- Years of Coeducation at Notre have women as well as men in na and member of the first fully Dame,” commemorating the the mix.” coeducated Notre Dame fresh- 40th anniversary of coeducation Dr. -

Museum of the Moving Image Presents Comprehensive Terrence Malick Retrospective

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE PRESENTS COMPREHENSIVE TERRENCE MALICK RETROSPECTIVE Moments of Grace: The Collected Terrence Malick includes all of his features, some alternate versions, and a preview screening of his new film A Hidden Life November 15–December 8, 2019 Astoria, New York, November 12, 2019—In celebration of Terrence Malick’s new film, the deeply spiritual, achingly ethical, and politically resonant A Hidden Life, Museum of the Moving Image presents the comprehensive retrospective Moments of Grace: The Collected Terrence Malick, from November 15 through December 8. The films in the series span a period of nearly 50 years, opening with Malick’s 1970s breakthroughs Badlands (1973) and Days of Heaven (1978), through his career-revival masterworks The Thin Red Line (1998) and The New World (2005), and continuing with his 21st- century films—from Cannes Palme d’Or winner The Tree of Life (2011); the trio of To the Wonder (2012), Knight of Cups (2015), and Song to Song (2017); and sole documentary project Voyage of Time (2016)—through to this year’s A Hidden Life. Two of these films will be presented in alternate versions—Voyage of Time and The New World—a testament to Malick’s ambitious and exploratory approach to editing. In addition to Malick’s own feature films, the series includes Pocket Money (1972), an ambling buddy comedy with Lee Marvin and Paul Newman, which he wrote (but did not direct), and Thy Kingdom Come (2018), the documentary featurette shot on the set of To the Wonder by photographer Eugene Richards.