Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRUST FALL by Al Schnupp

1 TRUST FALL by Al Schnupp A Twisted Version of a Classic Tale with Four Puppet Interludes CHARACTERS Daedalus, sculptor and inventor, living in Piraeus, near Athens Icarus, son of Daedalus Lydia, model for Daedalus Takus, agent for Daedalus King Minos of Crete Ariadene, Daughter of King Minos Phidias, Sculptor from Athens Soldier King Cocalos of Sicily Cyrene, Daughter of King Cocalos PUPPET INTERLUDES (Ensemble of Puppeteers) 1. The Nighttime Adventures of Chickens - as Imagined by Icarus Performed in a manual cinema style – live animation with projected images made from acetate and paper. 2. Daedalus Conceives a Machine to Delight his Son Performed in a mechanical automaton style 3. The Strange Dream of Takus (The Sorcery of Medea/The Death of Pelias) Performed with marionettes. 4. Minos Continues His Mad Search for Daedalus Performed with a modified Bunraku-style puppet. These are jolly, fun-loving characters. Even in intense moments of conflict, there should be an underlying sense of humor, sass and mischievous exchange. Casting for seven actors: One actor can play Phidias, Soldier and King Cocalos. One actress can play Ariadene and Cyrene. Al Schnupp [email protected] 805-215-6462 www.playsanddesigns.com 2 SCENE ONE THE STUDIO OF DAEDALUS (LYDIA, a scantly-clad model in her early thirties, holds a pose as DAEDALUS , in his late thirties, hammers away at his stone sculpture. A long moment passes). LYDIA (Slowly). Do you ever wonder what your female subjects might be thinking as you chip away…sculpting them in stone? DAEDALUS No! LYDIA Until you do, your creatures will just be cock teasers…fantasies for desperate, lonely men…nothing more. -

Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML Advanced

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. Summaries of the Trojan Cycle Search the GML advanced Sections in this Page Introduction Trojan Cycle: Cypria Iliad (Synopsis) Aethiopis Little Iliad Sack of Ilium Returns Odyssey (Synopsis) Telegony Other works on the Trojan War Bibliography Introduction and Definition of terms The so called Epic Cycle is sometimes referred to with the term Epic Fragments since just fragments is all that remain of them. Some of these fragments contain details about the Theban wars (the war of the SEVEN and that of the EPIGONI), others about the prowesses of Heracles 1 and Theseus, others about the origin of the gods, and still others about events related to the Trojan War. The latter, called Trojan Cycle, narrate events that occurred before the war (Cypria), during the war (Aethiopis, Little Iliad, and Sack of Ilium ), and after the war (Returns, and Telegony). The term epic (derived from Greek épos = word, song) is generally applied to narrative poems which describe the deeds of heroes in war, an astounding process of mutual destruction that periodically and frequently affects mankind. This kind of poetry was composed in early times, being chanted by minstrels during the 'Dark Ages'—before 800 BC—and later written down during the Archaic period— from c. 700 BC). Greek Epic is the earliest surviving form of Greek (and therefore "Western") literature, and precedes lyric poetry, elegy, drama, history, philosophy, mythography, etc. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell

STUDY GUIDE Photo of Mark L. Montgomery, Stephanie Andrea Barron, and Sandra Marquez by joe mazza/brave lux, inc Sponsored by Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell SETTING The action takes place in east-central Greece at the port of Aulis, on the Euripus Strait. The time is approximately 1200 BCE. CHARACTERS Agamemnon father of Iphigenia, husband of Clytemnestra and King of Mycenae Menelaus brother of Agamemnon Clytemnestra mother of Iphigenia, wife of Agamemnon Iphigenia daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra Achilles son of Peleus Chorus women of Chalcis who came to Aulis to see the Greek army Old Man servant of Agamemnon, was given as part of Clytemnestra’s dowry Messenger ABOUT THE PLAY Iphigenia in Aulis is the last existing work of the playwright Euripides. Written between 408 and 406 BCE, the year of Euripides’ death, the play was first produced the following year in a trilogy with The Bacchaeand Alcmaeon in Corinth by his son, Euripides the Younger, and won the first place at the Athenian City Dionysia festival. Agamemnon Costume rendering by Jacqueline Firkins. 2 SYNOPSIS At the start of the play, Agamemnon reveals to the Old Man that his army and warships are stranded in Aulis due to a lack of sailing winds. The winds have died because Agamemnon is being punished by the goddess Artemis, whom he offended. The only way to remedy this situation is for Agamemnon to sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia, to the goddess Artemis. Agamemnon then admits that he has sent for Iphigenia to be brought to Aulis but he has changed his mind. -

Ovid Book 12.30110457.Pdf

METAMORPHOSES GLOSSARY AND INDEX The index that appeared in the print version of this title was intentionally removed from the eBook. Please use the search function on your eReading device to search for terms of interest. For your reference, the terms that ap- pear in the print index are listed below. SINCE THIS index is not intended as a complete mythological dictionary, the explanations given here include only important information not readily available in the text itself. Names in parentheses are alternative Latin names, unless they are preceded by the abbreviation Gr.; Gr. indi- cates the name of the corresponding Greek divinity. The index includes cross-references for all alternative names. ACHAMENIDES. Former follower of Ulysses, rescued by Aeneas ACHELOUS. River god; rival of Hercules for the hand of Deianira ACHILLES. Greek hero of the Trojan War ACIS. Rival of the Cyclops, Polyphemus, for the hand of Galatea ACMON. Follower of Diomedes ACOETES. A faithful devotee of Bacchus ACTAEON ADONIS. Son of Myrrha, by her father Cinyras; loved by Venus AEACUS. King of Aegina; after death he became one of the three judges of the dead in the lower world AEGEUS. King of Athens; father of Theseus AENEAS. Trojan warrior; son of Anchises and Venus; sea-faring survivor of the Trojan War, he eventually landed in Latium, helped found Rome AESACUS. Son of Priam and a nymph AESCULAPIUS (Gr. Asclepius). God of medicine and healing; son of Apollo AESON. Father of Jason; made young again by Medea AGAMEMNON. King of Mycenae; commander-in-chief of the Greek forces in the Trojan War AGLAUROS AJAX. -

Antigone by Sophocles Scene 4, Ode 4, Scene 5, Paean and Exodos

Antigone by Sophocles Scene 4, Ode 4, Scene 5, Paean and Exodos By: Anmol Singh, Kesia Santos, and Yuri Seo Biographical, Cultural, and Historical Background The Greek Theater - Sophocles was one of the prominent figures in Greek theater. - Plays were performed in outdoor areas. - There were a limited number of actors and a chorus.6 - Antigone was mostly likely performed in the same fashion. AS Family Tree YS What do Scene 4, Ode 4, Scene 5, Paean and Exodos of Antigone focus on? - Family Conflict (internal and external) - Death (tragedy) - Poor judgment - Feeling and thinking - Fate - Loyalty - Love YS Genres & Subgenres Tragedy - Not completely like modern tragedies (ex. sad & gloomy). - Tragedies heavily used pathos (Greek for suffering). - Used masks and other props. - Were a form of worship to Dionysus.7 AS Tragic Hero - Antigone and Creon are both like tragic heros. - Each have their own hamartia which leads to their downfalls.8,9 AS Family Conflict & Tragedy in Antigone - Antigone hangs herself - Haimon stabs himself - Eurydice curses Creon and blames him for everything - Eurydice kills herself YS Dominant Themes Family: The story of Niobe - Antigone relates her story to the story of Niobe. - Antigone says “How often have I hear the story of Niobe, Tantalus’s wretched daughter…” (18) - Chorus tells Antigone that Niobe “was born of heaven,” but Antigone is a woman. YS Womanhood - Antigone defies the place a woman is supposed to have during this time period - Antigone and Ismene contrast each other - Creon is the prime example of the beliefs that males hold during this period KS Power and Corruption: Dryas and Lycurgus - A character the chorus compares to Antigone is Lycurgus. -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

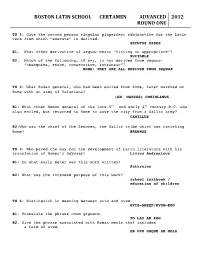

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

Greek Mythology #23: DIONYSUS by Joy Journeay

Western Regional Button Association is pleased to share our educational articles with the button collecting community. This article appeared in the August 2017 WRBA Territorial News. Enjoy! WRBA gladly offers our articles for reprint, as long as credit is given to WRBA as the source, and the author. Please join WRBA! Go to www.WRBA.us Greek Mythology #23: DIONYSUS by Joy Journeay God of: Grape Harvest, Winemaking, Wine, Ritual Madness, Religious Ecstasy, Fertility and Theatre Home: MOUNT OLYMPUS Symbols: Thyrus, grapevine, leopard skin Parents: Zeus and Semele Consorts: Adriane Siblings: Ares, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Hebe, Hermes, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Perseus, Minos, the Muses, the Graces Roman Counterpart: Bacchus, Liber Dionysus’ mother was mortal Semele, daughter of a king of Thebes, and his father was Zeus, king of the gods. Dionysus was the only Olympian god to have a mortal parent. He was the god of fertility, wine and the arts. His nature reflected the duality of wine: he gave joy and divine ecstasy, or brutal and blinding rage. He and his followers could not be contained by bonds. One would imagine that being the god of “good times” could be a pretty easy and happy existence. Unfortunately, this just doesn’t happen in the world of Greek mythology. Dionysus is called “twice born.” His mother, Semele, was seduced by a Greek god, but Semele did not know which god was her lover. Fully aware of her husband’s infidelity, the jealous Hera went to Semele in disguise and convinced her to see her god lover in his true form. -

Trojan War - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Trojan War from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for the 1997 Film, See Trojan War (Film)

5/14/2014 Trojan War - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Trojan War From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For the 1997 film, see Trojan War (film). In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen Trojan War from her husband Menelaus king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has been narrated through many works of Greek literature, most notably through Homer's Iliad. The Iliad relates a part of the last year of the siege of Troy; its sequel, the Odyssey describes Odysseus's journey home. Other parts of the war are described in a cycle of epic poems, which have survived through fragments. Episodes from the war provided material for Greek tragedy and other works of Greek literature, and for Roman poets including Virgil and Ovid. The war originated from a quarrel between the goddesses Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite, after Eris, the goddess of strife and discord, gave them a golden apple, sometimes known as the Apple of Discord, marked "for the fairest". Zeus sent the goddesses to Paris, who judged that Aphrodite, as the "fairest", should receive the apple. In exchange, Aphrodite made Helen, the most beautiful Achilles tending the wounded Patroclus of all women and wife of Menelaus, fall in love with Paris, who (Attic red-figure kylix, c. 500 BC) took her to Troy. Agamemnon, king of Mycenae and the brother of Helen's husband Menelaus, led an expedition of Achaean The war troops to Troy and besieged the city for ten years because of Paris' Setting: Troy (modern Hisarlik, Turkey) insult. -

The Thebaid Europa, Cadmus and the Birth of Dionysus

The Thebaid Europa, Cadmus and the birth of Dionysus Caesar van Everdingen. Rape of Europa. 1650 Zeus = Io Memphis = Epaphus Poseidon = Libya Lysianassa Belus Agenor = Telephassa In the Danaid, we followed the descendants of Belus. The Thebaid follows the descendants of Agenor Agenor = Telephassa Cadmus Phoenix Cylix Thasus Phineus Europa • Agenor migrated to the Levant and founded Sidon • But see Josephus, Jewish Antiquities i.130 - 139 • “… for Syria borders on Egypt, and the Phoenicians, to whom Sidon belongs, dwell in Syria.” (Hdt. ii.116.6) The Levant Levant • Jericho (9000 BC) • Damascus (8000) • Biblos (7000) • Sidon (4000) Biblos Damascus Sidon Tyre Jericho Levant • Canaanites: • Aramaeans • Language, not race. • Moved to the Levant ca. 1400-1200 BC • Phoenician = • purple dye people Biblos Damascus Sidon Tyre Agenor = Telephassa Cadmus Phoenix Cylix Thasus Phineus Europa • Zeus appeared to Europa as a bull and carried her to Crete. • Agenor sent his sons in search of Europa • Don’t come home without her! • The Rape of Europa • Maren de Vos • 1590 Bilbao Fine Arts Museum (Spain) Image courtesy of wikimedia • Rape of Europa • Caesar van Everdingen • 1650 • Image courtesy of wikimedia • Europe Group • Albert Memorial • London, 1872. • A memorial for Albert, husband of Queen Victoria. Crete Europa = Zeus Minos Sarpedon Rhadamanthus • Asterius, king of Crete, married Europa • Minos became king of Crete • Sarpedon king of Lycia • Rhadamanthus king of Boeotia The Brothers of Europa • Phoenix • Remained in Phoenicia • Cylix • Founded