Home Birth in Maine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCPS TV Dec 2018.Xlsx

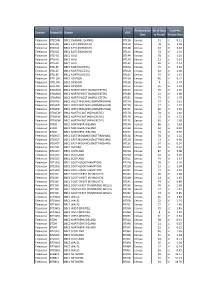

Total Per Performance No of Days Domain Station IDStation UDC Minute Date in Period Rate TELEVISION 0105 HOME NON-PEAK S0395 Census 62 £0.69 TELEVISION 0105 HOME PEAK S0396 Census 60 £1.38 TELEVISION 0106 ALIBI NON-PEAK S0373 Census 62 £0.63 TELEVISION 0106 ALIBI PEAK S0374 Census 60 £1.26 TELEVISION 0107 GOLD CENSUS NON-PEAK S1168 Census 61 £0.93 TELEVISION 0107 GOLD CENSUS PEAK S1169 Census 58 £1.87 TELEVISION 0172 GOOD FOOD NON-PEAK S0387 Census 62 £0.66 TELEVISION 0172 GOOD FOOD PEAK S0388 Census 60 £1.33 TELEVISION 0173 YESTERDAY CENSUS NON-PEAK S1574 Census 62 £1.24 TELEVISION 0173 YESTERDAY CENSUS PEAK S1575 Census 60 £2.49 TELEVISION 0175 DAVE CENSUS NON PEAK S1615 Census 62 £2.33 TELEVISION 0175 DAVE CENSUS PEAK S1616 Census 60 £4.66 TELEVISION 0177 EDEN NON-PEAK S0385 Census 62 £0.67 TELEVISION 0177 EDEN PEAK S0386 Census 60 £1.34 TELEVISION 0178 REALLY NON-PEAK S0397 Census 62 £1.18 TELEVISION 0178 REALLY PEAK S0398 Census 60 £2.37 TELEVISION 0180 W CENSUS NON PEAK S1576 Census 62 £0.60 TELEVISION 0180 W CENSUS PEAK S1577 Census 60 £1.19 TELEVISION 0201 DRAMA NON-PEAK S1773 Census 62 £2.56 TELEVISION 0201 DRAMA PEAK S1774 Census 60 £5.12 TELEVISION BT1EAS BBC1 EAST (NORWICH) HIGH PEAK BT12A Census 46 £3.04 TELEVISION BT1EAS BBC1 EAST (NORWICH) LOW PEAK BT12B Census 7 £2.18 TELEVISION BT1EAS BBC1 EAST (NORWICH) NON PEAK BT12C Census 40 £1.31 TELEVISION BT1HUL BBC1 HULL HIGH PEAK BT14A Census 49 £0.33 TELEVISION BT1LEE BBC1 NORTH (LEEDS) HIGH PEAK BT16A Census 53 £3.32 TELEVISION BT1LEE BBC1 NORTH (LEEDS) NON PEAK BT16C Census -

BARB Quarterly Reach Report- Quarter Q3 2019 (BARB Weeks

BARB Quarterly Reach Report- Quarter Q3 2019 (BARB weeks 2658-2670) Individuals 4+ Weekly Reach Monthly Reach Quarterly Reach 000s % 000s % 000s % TOTAL TV 53719 89.0 58360 96.7 59678 98.9 4Music 2138 3.5 5779 9.6 11224 18.6 4seven 4379 7.3 11793 19.5 21643 35.9 5SELECT 2574 4.3 6663 11.0 11955 19.8 5Spike 4468 7.4 10115 16.8 16594 27.5 5Spike+1 199 0.3 625 1.0 1333 2.2 5STAR 5301 8.8 13032 21.6 22421 37.2 5STAR+1 643 1.1 2122 3.5 4759 7.9 5USA 3482 5.8 6742 11.2 10374 17.2 5USA+1 467 0.8 1242 2.1 2426 4.0 92 News 101 0.2 280 0.5 588 1.0 A1TV 101 0.2 285 0.5 627 1.0 Aaj Tak 164 0.3 364 0.6 698 1.2 ABN TV 105 0.2 259 0.4 548 0.9 ABP News 145 0.2 333 0.6 625 1.0 Akaal Channel 87 0.1 287 0.5 724 1.2 Alibi 1531 2.5 3383 5.6 5964 9.9 Alibi+1 299 0.5 740 1.2 1334 2.2 AMC 96 0.2 248 0.4 565 0.9 Animal Planet 405 0.7 1107 1.8 2542 4.2 Animal Planet+1 107 0.2 337 0.6 678 1.1 Arise News 43 0.1 133 0.2 336 0.6 ARY Family 119 0.2 331 0.5 804 1.3 ATN Bangla 101 0.2 243 0.4 481 0.8 B4U Movies 255 0.4 595 1.0 1021 1.7 B4U Music 226 0.4 571 0.9 1192 2.0 B4U Plus 91 0.2 309 0.5 766 1.3 BBC News 6774 11.2 11839 19.6 17310 28.7 BBC Parliament 990 1.6 2667 4.4 5430 9.0 BBC RB 1 469 0.8 1582 2.6 3987 6.6 BBC RB 601 609 1.0 1721 2.9 3457 5.7 BBC Scotland 1421 2.4 3216 5.3 5605 9.3 BBC1 39360 65.2 49428 81.9 54984 91.2 BBC2 27006 44.8 41055 68.1 49645 82.3 BBC4 8429 14.0 18385 30.5 28278 46.9 BET:BlackEntTv 163 0.3 552 0.9 1375 2.3 BLAZE 2181 3.6 4677 7.8 8098 13.4 Boomerang 685 1.1 1751 2.9 3429 5.7 Boomerang+1 266 0.4 790 1.3 1631 2.7 Box Hits 405 0.7 1247 -

CHANNEL GUIDE AUGUST 2020 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit

KEY 1 Player 4 Full House PREMIUM CHANNELS CHANNEL GUIDE AUGUST 2020 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit + 266 National Geographic 506 Sky Sports F1® HD 748 Create and Craft 933 BBC Radio Foyle HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU CAN GET + 267 National Geographic +1 507 Sky Sports Action HD 755 Gems TV 934 BBC Radio NanGaidheal + 268 National Geographic HD 508 Sky Sports Arena HD 756 Jewellery Maker 936 BBC Radio Cymru 1. Match your package to the column 1 2 3 4 5 6 269 Together 509 Sky Sports News HD 757 TJC 937 BBC London 101 BBC One/HD* + 270 Sky HISTORY HD 510 Sky Sports Mix HD 951 Absolute 80s 2. If there’s a tick in your column, you get that channel Sky One + 110 + 271 Sky HISTORY +1 511 Sky Sports Main Event INTERNATIONAL 952 Absolute Classic Rock 3. If there’s a plus sign, it’s available as + 272 Sky HISTORY2 HD 512 Sky Sports Premier League 1 2 3 4 5 6 958 Capital part of a Personal Pick collection 273 PBS America 513 Sky Sports Football 800 Desi App Pack 959 Capital XTRA 274 Forces TV 514 Sky Sports Cricket 801 Star Gold HD 960 Radio X + 275 Love Nature HD 515 Sky Sports Golf 802 Star Bharat 963 Kiss FM 516 Sky Sports F1® 803 Star Plus HD + 167 TLC HD 276 Smithsonian Channel HD ENTERTAINMENT 517 Sky Sports Action 805 SONY TV ASIA HD ADULT 168 Investigation Discovery 277 Sky Documentaries HD 1 2 3 4 5 6 + 518 Sky Sports Arena 806 SONY MAX HD 100 Virgin Media Previews HD 169 Quest -

Should We Have Made War in the Gulf? 3 Stony Brook Students Split on U.S

<i -* Stony Brooi-^ & W ^ Z:C ^Cr-^ --- ^^I Tuesday 1991 ^^ -A '^^'S^^^^^-^^Sr^'IV L------I January 29. ^^^ T^Vy£^(? yy^ ^W y^ ~~~~~~~~~~~Volume34, Number 30 1^^ €/l>C/€/<^Of~~~~~~~~yV/J €^~~ STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW~ YORK AT STONY BROOK - - M | T,.- -I In ...^ r ^* w* ,.* , , * * ** - » > l'v-: _ , ' l;,, 2 . ' ... {':''-:.,.^e _ Statesman/Christopher Reid Anti-war protestors urge President Bush to read their lips during yesterday's rally. -Should We Have Made War in the Gulf? 3 Stony Brook Students Split on U.S. Role - Page -- -~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ While you were away... December 24- TwentyIneAmerican Baker leaves for his meeting with Aziz. caii/wJan Israeli in ferry ac- 7 - Back Jan 7 - Former Cincinnati Reds star Pete Welcomlne cident are honored. Rose leaves jail after six months. Dec 25- President Bush says the troops The A-12, the Navy's stealth fighter, is SUWNY nn: ot ready for a ground assault. grounded by Secretary of Defense Dick balman Rushdie's repentance was rejected Cheney. by the Ayatollah. Gorbachev orders the Soviet troops to round *New "'SEPy *Tai-Chi& *Medically Supervised up all draft evaders in Lithuania. Aerobics Classes Yoga classes weight loss programs Dec. 26 - The US Census Bureau reports Rioting in Haiti over Lafontant's failed coup 249,632,692 Americans. leaves 36 people dead. *Computerized Nancy Cruzan dies at age 26 - was focus of Iraq seeks France's aid in the UN. Stairmaster, international debate over life-support sys- Treadmills & tems. Jan 8 - Pan Am files for bankruptcy. Soviet President Gorbachev picks Gennady Soviet troops enter Lithuania to enforce the Aerobicycles Yanayev as Vice President. -

CHANNEL GUIDE JULY 2021 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit

KEY 1 Player 4 Full House PREMIUM CHANNELS CHANNEL GUIDE JULY 2021 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit 269 Together 513 Sky Sports Football 802 Utsav Bharat ADULT HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU CAN GET + 270 Sky HISTORY HD 514 Sky Sports Cricket 803 Utsav Plus HD 271 Sky HISTORY +1 515 Sky Sports Golf 805 SONY TV HD To PIN protect these channels, go to + virginmedia.com/pin 1. Match your package to the column 1 2 3 4 5 6 + 272 Sky HISTORY2 HD 516 Sky Sports F1® 806 SONY MAX HD 101 BBC One/HD* 273 PBS America 517 Sky Sports NFL 807 SONY SAB 1 2 3 4 5 6 2. If there’s a tick in your column, you get that channel 110 Sky One + 274 Forces TV 518 Sky Sports Arena 808 SONY MAX 2 969 Adult Previews 3. If there’s a plus sign, it’s available as 276 Smithsonian Channel HD + 519 Sky Sports News 809 Zee TV 970 Television X: The Fantasy part of a Personal Pick collection 277 Sky Documentaries HD + 520 Sky Sports Mix 810 Zee Cinema HD Channel + 278 Sky Documentaries + 521 Eurosport 1 HD 815 B4U Movies 971 Babes & Brazzers 279 Sky Nature HD + 522 Eurosport 2 HD 816 B4U Music 972 Adult Channel 526 MUTV 825 Colors Gujarati XXX Brits + 167 TLC HD + 280 Sky Nature 973 ENTERTAINMENT 527 BT Sport 1 HD 826 Colors TV HD 974 Xrated 40 Plus 1 2 3 4 5 6 + 168 Investigation Discovery 285 Food Network 286 HGTV 528 BT Sport 2 HD 827 Colors Rishtey 976 TV X Porn Stars 2 100 Virgin Media Previews HD 169 Quest HD 290 HGTV +1 529 BT Sport -

Virgin Tv 360 Channel Guide June 2021

VIRGIN TV 360 CHANNEL GUIDE JUNE 2021 KEY HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU CAN GET 1 Mixit 1. Match your package to the column 2 Maxit 2. If there’s a tick in your column, you get that channel 1 2 PREMIUM CHANNELS 3. If there’s a plus sign, it’s available as part of a 101 BBC One/HD* Personal Pick collection + PERSONAL PICK � 4. If a channel is available in both SD and HD, + 110 Sky One/HD and your package includes the HD version, you will automatically see the HD content ENTERTAINMENT SPORT 1 2 1 2 100 Virgin TV Highlights 501 Sky Sports Main Event/HD� 101 BBC One/HD* 502 Sky Sports Premier League/HD� 102 BBC Two HD* 503 Sky Sports Football/HD� 103 ITV HD & STV HD & UTV HD* 504 Sky Sports Cricket/HD� 104 Channel 4/HD & S4C HD*� 505 Sky Sports Golf/HD� 105 Channel 5/HD� 506 Sky Sports F1®/HD� 106 E4/HD� 507 Sky Sports NFL/HD� 107 BBC Four HD 508 Sky Sports Arena/HD� 108 BBC One HD & BBC Scotland HD* + 509 Sky Sports News/HD� + 109 Sky One/HD� + 510 Sky Sports Mix/HD� + 111 Sky Witness/HD� + 521 Eurosport 1 HD 113 UTV HD* + 522 Eurosport 2 HD 114 ITV +1 & STV +1* 526 MUTV 115 ITV2/HD� 527 BT Sport 1 HD 116 ITV2 +1 528 BT Sport 2 HD 117 ITV3/HD� 529 BT Sport 3 HD 118 ITV4/HD� 530 BT Sport ESPN HD 119 ITVBe/HD� 531 BT Sport Ultimate 120 ITVBe +1 & BBC Alba* 535 Sky Sports Racing HD + 121 Sky Comedy/HD� 536 Racing TV HD 123 Sky Arts/HD� 544 LFC TV HD + 124 GOLD HD 546 BoxNation + 125 W/HD� 551 Premier Sports 1 HD + 126 alibi/HD� 552 Premier Sports 2 HD 127 Dave/HD� 553 FreeSports HD -

Channel Guide July 2019

CHANNEL GUIDE JULY 2019 KEY HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU CAN GET 1 PLAYER 1 MIXIT 1. Match your package 2. If there’s a tick in 3. If there’s a plus sign, it’s to the column your column, you available as part of a 2 MIX 2 MAXIT get that channel Personal Pick collection 3 FUN PREMIUM CHANNELS 4 FULL HOUSE + PERSONAL PICKS 1 2 3 4 5 6 101 BBC One/HD* + 110 Sky One ENTERTAINMENT SPORT 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 100 Virgin Media Previews HD 501 Sky Sports Main Event HD 101 BBC One/HD* 502 Sky Sports Premier League HD 102 BBC Two HD 503 Sky Sports Football HD 103 ITV/STV HD* 504 Sky Sports Cricket HD 104 Channel 4 505 Sky Sports Golf HD 105 Channel 5 506 Sky Sports F1® HD 106 E4 507 Sky Sports Action HD 107 BBC Four HD 508 Sky Sports Arena HD 108 BBC One HD/BBC Scotland HD* 509 Sky Sports News HD 109 Sky One HD 510 Sky Sports Mix HD + 110 Sky One 511 Sky Sports Main Event 111 Sky Witness HD 512 Sky Sports Premier League + 112 Sky Witness 513 Sky Sports Football 113 ITV HD* 514 Sky Sports Cricket 114 ITV +1 515 Sky Sports Golf 115 ITV2 516 Sky Sports F1® 116 ITV2 +1 517 Sky Sports Action 117 ITV3 518 Sky Sports Arena 118 ITV4 + 519 Sky Sports News 119 ITVBe + 520 Sky Sports Mix 120 ITVBe +1 + 521 Eurosport 1 HD + 121 Sky Two + 522 Eurosport 2 HD + 122 Sky Arts + 523 Eurosport 1 123 Pick + 524 Eurosport 2 + 124 GOLD HD 526 MUTV + 125 W 527 BT Sport 1 HD + 126 alibi 528 -

Broadcast Website Info D183 MCPS.Xlsx

Performance No of Days Total Per Domain Station IDStation UDC Date in Period Minute Rate Television BT1CHN BBC1 CHANNEL ISLANDS BT11A Census 51£ 0.11 Television BT1EAS BBC1 EAST (NORWICH) BT12A Census 78£ 3.04 Television BT1EAS BBC1 EAST (NORWICH) BT12B Census 13£ 2.18 Television BT1EAS BBC1 EAST (NORWICH) BT12C Census 74£ 1.31 TelevisionBT1HUL BBC1 HULL BT14A Census 78£ 0.33 TelevisionBT1HUL BBC1 HULL BT14B Census 13£ 0.24 TelevisionBT1HUL BBC1 HULL BT14C Census 65£ 0.14 Television BT1LEE BBC1 NORTH (LEEDS) BT16A Census 77£ 3.32 Television BT1LEE BBC1 NORTH (LEEDS) BT16B Census 12£ 2.38 Television BT1LEE BBC1 NORTH (LEEDS) BT16C Census 74£ 1.42 Television BT1LON BBC1 LONDON BT15A Census 46£ 5.22 Television BT1LON BBC1 LONDON BT15B Census 4£ 3.74 Television BT1LON BBC1 LONDON BT15C Census 65£ 2.24 Television BT1MAN BBC1 NORTH WEST (MANCHESTER) BT18A Census 78£ 4.16 Television BT1MAN BBC1 NORTH WEST (MANCHESTER) BT18B Census 13£ 2.98 Television BT1MAN BBC1 NORTH WEST (MANCHESTER) BT18C Census 73£ 1.79 Television BT1MID BBC1 WEST MIDLANDS (BIRMINGHAM) BT27A Census 74£ 3.23 Television BT1MID BBC1 WEST MIDLANDS (BIRMINGHAM) BT27B Census 12£ 2.32 Television BT1MID BBC1 WEST MIDLANDS (BIRMINGHAM) BT27C Census 60£ 1.39 Television BT1NEW BBC1 NORTH EAST (NEWCASTLE) BT17A Census 78£ 2.40 Television BT1NEW BBC1 NORTH EAST (NEWCASTLE) BT17B Census 13£ 1.72 Television BT1NEW BBC1 NORTH EAST (NEWCASTLE) BT17C Census 65£ 1.03 Television BT1NI BBC1 NORTHERN IRELAND BT19A Census 86£ 1.29 Television BT1NI BBC1 NORTHERN IRELAND BT19B Census 33£ 0.92 Television -

CHANNEL GUIDE MAY 2021 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit

KEY 1 Player 4 Full House PREMIUM CHANNELS CHANNEL GUIDE MAY 2021 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit + 266 National Geographic 508 Sky Sports Arena HD INTERNATIONAL 952 Absolute Classic Rock HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU CAN GET + 267 National Geographic +1 509 Sky Sports News HD 1 2 3 4 5 6 958 Capital + 268 National Geographic HD 510 Sky Sports Mix HD 800 Desi App Pack 959 Capital XTRA 1. Match your package to the column 1 2 3 4 5 6 269 Together 511 Sky Sports Main Event 801 Utsav Gold HD 960 Radio X 101 BBC One/HD* + 270 Sky HISTORY HD 512 Sky Sports Premier League 802 Utsav Bharat 963 Kiss FM 2. If there’s a tick in your column, you get that channel + 110 Sky One + 271 Sky HISTORY +1 513 Sky Sports Football 803 Utsav Plus HD 3. If there’s a plus sign, it’s available as + 272 Sky HISTORY2 HD 514 Sky Sports Cricket 805 SONY TV HD ADULT part of a Personal Pick collection 273 PBS America 515 Sky Sports Golf 806 SONY MAX HD ® To PIN protect these channels, go to 274 Forces TV 516 Sky Sports F1 807 SONY SAB virginmedia.com/pin 276 Smithsonian Channel HD 517 Sky Sports NFL 808 SONY MAX 2 518 Sky Sports Arena 1 2 3 4 5 6 165 Pick 277 Sky Documentaries HD 809 Zee TV ENTERTAINMENT + 519 Sky Sports News 969 Adult Previews 1 2 3 4 5 6 166 S4C HD* + 278 Sky Documentaries 810 Zee Cinema HD + 520 Sky Sports Mix 970 Television X: The Fantasy 100 Virgin Media Previews HD + 167 TLC HD 279 Sky Nature HD 815 B4U Movies -

We're Making It Easier to Find Your Favourite Shows

We’re making it easier to find your favourite shows Here’s a quick rundown of the changes we’re introducing: • Documentary channels will be moved up the TV Guide to sit alongside Entertainment channels • +1 channels will be listed in a new menu on the TV Guide • +1s from Entertainment & Documentaries move to new linked channel numbers (e.g, Sky One - 106, Sky One+1 - 206) PAGE 1 Entertainment News, Specialist, Secondary Channels, Movies & Sports & Music International & Adult & Radio & Documentaries Religion, Kids & Shopping Entertainment & Documentaries 101 RTÉ One HD 201 RTÉ One+1 171 Disc.History 271 Disc.History+1 954 BBC One London (AD) 102 RTÉ Two HD 172 Discovery Shed 969 BBC Two Eng (AD) 103 TV3 HD 203 TV3+1 173 BET:BlackEntTv 976 BBC One HD (AD) 104 TG4 HD 174 VH1 994 Sky Atlantic VIP 105 3e HD 175 BEN 995 Sky Atlantic VIP HD 106 Sky One HD 206 Sky One+1 177 Home & Health 277 HomeHealth+1 996 Chl Line-up 107 Sky Living HD 207 Sky Living+1 178 DMAX 278 DMAX+1 998 Sky Intro 108 Sky Atlantic HD 208 Sky Atlantic+1 179 True Ent 279 True Ent+1 999 Channel 999 109 W HD 209 W+1 180 truTV 280 truTV+1 110 GOLD 210 GOLD+1 181 Sony Crime 2 111 Dave HD 211 Dave ja vu 182 GNTV 112 Comedy Central 212 ComedyCent+1 183 VICE 113 Universal 213 Universal+1 184 Horse & Country 114 SYFY HD 214 SYFY+1 185 propeller 116 Be3 187 Blaze 121 SkySp Mix HD 188 Disc.Turbo 288 Disc.Turbo+1 122 Sky Arts HD 189 Property Show 123 Sky Two 190 Animal Planet HD 290 Animal Plnt+1 124 FOX HD 224 FOX+1 191 mytv 125 Discovery 225 Discovery+1 192 Showcase 292 Showcase+1 -

FREEVIEW DTT Multiplexes (UK Inc NI) Incorporating Planned Local TV and Temporary HD Muxes

As at 27 November 2019 FREEVIEW DTT Multiplexes (UK inc NI) incorporating planned Local TV and Temporary HD muxes 3PSB: Available from all transmitters (*primary and relay) 3 COM: From *80 primary transmitters only Temporary HD - 27 primary transmitters BBC A (PSB1) BBC A (PSB1) continued BBC B (PSB3) HD SDN (COM4) ARQIVA A (COM5) ARQIVA B (COM6) ARQIVA C (COM7) HD ARQIVA D (COM8) HD LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN 1 BBC ONE 101 BBC 1 Scot HD 12 QUEST 11 Pick 22 Ideal World 57 5USA+1 (from 6pm) 56 5STAR+1 BBC RADIO: 1 BBC ONE NI Cambridge, Lincolnshire, 101 BBC 1 Wales HD 13 E4 (Wales only) 17 Really 25 Yesterday 67 CBS Reality+1 64 Free Sports 722 Merseyside, Oxford, 1 BBC ONE Scot Solent, Somerset, 101 BBC ONE HD 16 QVC 19 Dave 29 4 Music 72 Quest Red+1 83 NOW XMAS Surrey, Tyne Tees, WM 1 BBC ONE Wales 101 BBC ONE NI HD 20 Drama 23 Create & Craft 31 5Spike 74 Jewellery Maker 89 Together TV+1 2 BBC TWO 102 BBC 2 Wales HD 21 5 USA 32 Sony Movies 35 QVC Beauty 86 More4+1 93 PBS America+1 2 BBC TWO NI BBC RADIO: 102 BBC TWO HD 26 ITVBe 38 Quest Red 36 QVC Style 92 Pick+1 96 Forces TV 726 BBC Solent Dorset 2 BBC TWO Wales BBC Stoke 102 BBC TWO NI HD 27 ITV2 +1 41 Food Network 37 DMAX 99 Smithsonian Channel 106 BBC FOUR HD 7 BBC ALBA (Scot only) 103 ITV HD 30 5 STAR 43 Gems TV 39 CBS Justice 107 BBC NEWS HD 111 QVC HD 9 BBC FOUR 103 ITV Wales HD 34 ITV3+1 (18:00-00:00) 45 Film4+1 42 Home 109 Channel 4+1 HD 112 QVC Beauty HD Sony Movies Action 9 BBC SCOTLAND (Scot only) BBC RADIO: 103 STV HD 40 46 Challenge 47 4seven 110 4seven HD 114 QUEST -

Virgin Tv 360 Channel Guide July 2021

VIRGIN TV 360 CHANNEL GUIDE JULY 2021 KEY HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU CAN GET 1 Mixit 1. Match your package to the column 2 Maxit 2. If there’s a tick in your column, you get that channel 1 2 PREMIUM CHANNELS 3. If there’s a plus sign, it’s available as part of a 101 BBC One/HD* Personal Pick collection + PERSONAL PICKS � 4. If a channel is available in both SD and HD, + 110 Sky One/HD and your package includes the HD version, you will automatically see the HD content ENTERTAINMENT SPORT 1 2 1 2 100 Virgin TV Highlights 501 Sky Sports Main Event/HD� 101 BBC One/HD* 502 Sky Sports Premier League/HD� 102 BBC Two HD* 503 Sky Sports Football/HD� 103 ITV HD & STV HD & UTV HD* 504 Sky Sports Cricket/HD� 104 Channel 4/HD & S4C HD*� 505 Sky Sports Golf/HD� 105 Channel 5/HD� 506 Sky Sports F1®/HD� 106 E4/HD� 507 Sky Sports NFL/HD� 107 BBC Four HD 508 Sky Sports Arena/HD� 108 BBC One HD & BBC Scotland HD* + 509 Sky Sports News/HD� + 109 Sky One/HD� + 510 Sky Sports Mix/HD� + 111 Sky Witness/HD� + 521 Eurosport 1 HD 113 UTV HD* + 522 Eurosport 2 HD 114 ITV +1 & STV +1* 526 MUTV 115 ITV2/HD� 527 BT Sport 1 HD 116 ITV2 +1 528 BT Sport 2 HD 117 ITV3/HD� 529 BT Sport 3 HD 118 ITV4/HD� 530 BT Sport ESPN HD 119 ITVBe/HD� 531 BT Sport Ultimate 120 ITVBe +1 & BBC Alba* 535 Sky Sports Racing HD + 121 Sky Comedy/HD� 536 Racing TV HD 123 Sky Arts/HD� 544 LFC TV HD + 124 GOLD HD 546 BoxNation + 125 W/HD� 551 Premier Sports 1 HD + 126 alibi/HD� 552 Premier Sports 2 HD 127 Dave/HD� 553 FreeSports HD 128 Really 554 LaLigaTV 129 Yesterday 130 Drama NEWS 131