International Reports 3/2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Date of Birth 21.02.1981 Place of Birth Göttingen, Germany

CURRICULUM VITAE PD DR. ANNA-LISA MÜLLER PERSONAL INFORMATION Date of birth 21.02.1981 Place of birth Göttingen, Germany SCIENTIFIC CAREER Since Nov. 2020 Deputy Head of the Working Group Human Geography University of Heidelberg, Germany 2019–2020 Senior Researcher Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies (IMIS), University of Osnabrück, Germany 2019 Habilitation, venia legendi “Humangeographie” Department of Geography, University of Bremen, Germany 2013–2019 Senior Researcher Department of Geography, University of Bremen, Germany 2–4/2017 Visiting Academic Durham University, UK 2013 PhD, grade “summa cum laude” Bielefeld University, Germany 2012–2013 Research Assistant Research Group Urban Metamorphoses, HafenCity University Hamburg, Germany PD DR. ANNA-LISA MÜLLER | CV | 1/25 2010–2012 Graduate Student & PhD candidate Bielefeld Graduate School in History and Sociology, Bielefeld University, Germany title of PhD thesis: Green Creative Cities. Designing a New Type of Cities of the 21st Century (in German) 2007–2010 Research Assistant Center of Excellence 16 Cultural Foundations of Integration, Department of Sociology, chair of Prof. Dr. Andreas Reckwitz, University of Konstanz, Germany 10/2004–6/2007 Graduate studies in sociology, German literature and philosophy (Magister-Hauptstudium), University of Konstanz, Germany; grade: “very good”, title of Master's thesis: “Subject, Language and Power in the Work of Judith Butler” 9/2003–7/2004 Undergraduate studies in sociology, University of Växjö, Sweden 10/2001–3/2003 Undergraduate -

Treasury, HUD Submit Housing Reform Plans Federal Reserve Proposes

In classic Greek mythology, a golden apple of discord inscribed "For the fairest" was awarded to Aphrodite, beginning a chain of events that led to the Trojan War. GrayRobinson's newsletter reports on the most recent issues, individuals, and discourse deemed fairest in Washington. September 6, 2019 . aaaand we’re back. How was your August? We are thankful that our offices in Melbourne and Jacksonville, among others, were spared the worst of Hurricane Dorian, but the hurricane season still has almost three months to run. Stay safe, everybody. Treasury, HUD submit housing reform plans Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson submitted two plans to the White House yesterday for ending the conservatorship of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, restructuring the government guarantees for housing loans, and protecting taxpayers from further liability. The Treasury report calls for almost 50 legislative changes to limit the government’s role in the secondary market, enhance taxpayer protections, and encourage private-sector competition. “At the same time, reform should not and need not wait on Congress,” the report said. The HUD plan would “refocus” the Federal Housing Administration on its “core mission of helping low- and moderate-income borrowers.” Mnuchin, Carson, and Federal Housing Finance Administration Director Mark Calabria will appear before the Senate Banking Committee next Tuesday to discuss the plans. Senate Banking Committee Chairman Mike Crapo (R- ID) said yesterday that many of the Treasury plan’s provisions corresponded to elements of his own proposal, and that he would prefer “to fix the housing finance system through legislation.” Federal Reserve proposes capital requirements for insurance companies that own banks Today the Federal Reserve published a long-awaited proposal to create a capital framework for the eight insurance companies that own banks. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

(1 of 432) Case:Case 18-15845,1:19-cv-01071-LY 01/27/2020, Document ID: 11574519, 41-1 FiledDktEntry: 01/29/20 123-1, Page Page 1 1 of of 432 239 FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT THE DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL No. 18-15845 COMMITTEE; DSCC, AKA Democratic Senatorial Campaign D.C. No. Committee; THE ARIZONA 2:16-cv-01065- DEMOCRATIC PARTY, DLR Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. OPINION KATIE HOBBS, in her official capacity as Secretary of State of Arizona; MARK BRNOVICH, Attorney General, in his official capacity as Arizona Attorney General, Defendants-Appellees, THE ARIZONA REPUBLICAN PARTY; BILL GATES, Councilman; SUZANNE KLAPP, Councilwoman; DEBBIE LESKO, Sen.; TONY RIVERO, Rep., Intervenor-Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Arizona Douglas L. Rayes, District Judge, Presiding (2 of 432) Case:Case 18-15845,1:19-cv-01071-LY 01/27/2020, Document ID: 11574519, 41-1 FiledDktEntry: 01/29/20 123-1, Page Page 2 2 of of 432 239 2 DNC V. HOBBS Argued and Submitted En Banc March 27, 2019 San Francisco, California Filed January 27, 2020 Before: Sidney R. Thomas, Chief Judge, and Diarmuid F. O’Scannlain, William A. Fletcher, Marsha S. Berzon*, Johnnie B. Rawlinson, Richard R. Clifton, Jay S. Bybee, Consuelo M. Callahan, Mary H. Murguia, Paul J. Watford, and John B. Owens, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge W. Fletcher; Concurrence by Judge Watford; Dissent by Judge O’Scannlain; Dissent by Judge Bybee * Judge Berzon was drawn to replace Judge Graber. Judge Berzon has read the briefs, reviewed the record, and watched the recording of oral argument held on March 27, 2019. -

Our Race Is Being Watched As a Sign of What's to Come in 2020 - Outl

Our race is being watched as a sign of what's to come in 2020 - Outl... https://ex.myhosting.com/owa/?ae=Item&t=IPM.Note&id=RgAA... Type here to search This Folder Address Book Options Log Off Mail Reply Reply to All Forward Move Delete Close Calendar Our race is being watched as a sign of what's to come in 2020 Contacts DanMcCready.com [[email protected]] Sent: Saturday, August 31, 2019 4:09 PM Email Settings To: Steve Johnston Deleted Items Drafts Inbox (31) Junk E-Mail Sent Items National Republicans are getting desperate, Steve. They know the polls are tied, and that we have a real chance of flipping this district. Click to view all folders 16-12 Grants Committee Just take a look at the Politico headline: 19-06 (41) 19-07 (39) 19-08 (40) Manage Folders... They’re terrified that Dan could win this historically red district. They’re watching this race as a sign of what’s to come in 2020. That’s why far-right Super PACs are dumping millions into our district. They know their only chance of winning is to try to drown out our message. We cannot afford to let that happen. Will you rush a $3 donation to our special election campaign? Dan needs our help to fight back. Your support will ensure that we have what it takes to compete with their outside spending. DONATE Look, people are already voting early, so we cannot wait until Election Day. It’s important that we turn out voters right now. -

PM Launches QP's Localisation Drive

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Qatar’s Adel switches QP signs deals worth to T3 QR9bn with major Can-Am international fi rms published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 11099 February 19, 2019 Jumada II 14, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals In brief Food festival at QATAR | Offi cial Amir congratulates Gambian president Oxygen Park His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, His Highness the Deputy Amir Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad al-Thani and from March 20 HE the Prime Minister and Minister of Interior Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser bin Khalifa al-Thani sent he tenth edition of Qatar Inter- yesterday cables of congratulations national Food Festival (QIFF) to Gambian President Adama Barrow Twill be held from March 20 to on the anniversary of his country’s 30 at Qatar Foundation’s (QF) Oxy- Independence Day. gen Park, offi cials from Qatar National Tourism Council (QNTC) and QF an- AMERICA | Politics nounced. The festival is Qatar’s longest-run- Trump’s emergency ning food and beverage tradition, com- declaration decried HE the Prime Minister and Interior Minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Nasser bin Khalifa al-Thani launches Qatar Petroleum’s Tawteen bining culinary arts with family enter- A small group of demonstrators initiative during a ceremony held in Doha yesterday. Page 24 tainment, and this year it celebrates rallied outside the White House its milestone edition at the heart of yesterday to protest President Education City, off ering a whole new Donald Trump’s declaration of format and exciting festivities for resi- a national emergency to fund a dents and visitors of all ages. -

On Valuation Studies and Climate Change

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Frisch, Thomas; Laser, Stefan; Matthäus, Sandra; Schendzielorz, Cornelia Article It's worth the trouble: On valuation studies and climate change economic sociology_the european electronic newsletter Provided in Cooperation with: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (MPIfG), Cologne Suggested Citation: Frisch, Thomas; Laser, Stefan; Matthäus, Sandra; Schendzielorz, Cornelia (2021) : It's worth the trouble: On valuation studies and climate change, economic sociology_the european electronic newsletter, ISSN 1871-3351, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (MPIfG), Cologne, Vol. 22, Iss. 2, pp. 10-14 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/232527 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Florida 26: Can Local Politics Trump Partisanship? 2020 House Ratings

This issue brought to you by 2020 House Ratings Toss-Up (2R, 4D) GA 7 (Open; Woodall, R) NY 11 (Rose, D) IA 3 (Axne, D) OK 5 (Horn, D) IL 13 (Davis, R) SC 1 (Cunningham, D) Tilt Democratic (10D, 1R) Tilt Republican (6R) JUNE 5, 2020 VOLUME 4, NO. 11 CA 21 (Cox, D) MN 1 (Hagedorn, R) CA 25 (Garcia, R) NJ 2 (Van Drew, R) GA 6 (McBath, D) PA 1 (Fitzpatrck, R) Florida 26: Can Local Politics IA 1 (Finkenauer, D) PA 10 (Perry, R) IA 2 (Open; Loebsack, D) TX 22 (Open; Olson, R) Trump Partisanship? ME 2 (Golden, D) TX 24 (Open; Marchant, R) MN 7 (Peterson, DFL) By Jacob Rubashkin NM 2 (Torres Small, D) NY 22 (Brindisi, D) GOP DEM Republicans are putting Tip O’Neill’s “All politics is local” to the UT 4 (McAdams, D) 116th Congress 201 233 ultimate test in Florida. GOP strategists generally believe that their VA 7 (Spanberger, D) Currently Solid 174 202 path back to the House majority lies in districts carried or narrowly lost Competitive 27 31 by President Donald Trump in 2016. Florida’s 26th is not one of those districts; it voted for Hillary Clinton by 16 points. Needed for majority 218 But this South Florida constituency, created after the 2010 redistricting cycle, offers some hope to the GOP. It’s shown a willingness to vote Lean Democratic (8D, 1R) Lean Republican (6R, 1L) for Republicans down ballot, and the national party was able to land a CA 48 (Rouda, D) MI 3 (Open; Amash, L) top-tier recruit to take on freshman Democrat Debbie Mucarsel-Powell, IL 14 (Underwood, D) MO 2 (Wagner, R) something Republicans have struggled to do in some more competitive KS 3 (Davids, D) NE 2 (Bacon, R) districts nationwide. -

Congress Approves Spending Bills House Approves USMCA

In classic Greek mythology, a golden apple of discord inscribed "For the fairest" was awarded to Aphrodite, beginning a chain of events that led to the Trojan War. GrayRobinson's newsletter reports on the most recent issues, individuals, and discourse deemed fairest in Washington. December 20, 2019 Are you tired? We’re tired. The House of Representatives debated and voted on two articles of impeachment against the President of the United States, but the House and Senate also voted on bills to fund the government through the end of the next fiscal year, and the House struck a deal with the White House on the US-Mexico-Canada free trade agreement (USMCA). We’re ready for the weekend. But first . Congress approves spending bills The House and Senate approved two spending bills that will keep the government running through September 30, 2020. HR 1158 provides funding for the Departments of Defense, Commerce, Justice, Treasury, and Homeland Security; the Judiciary; the independent agencies; and all related agencies. HR 1865 provides funding for the Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, Agriculture, Energy, Interior, Veterans Affairs, State, Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and all related agencies. Among provisions of interest to our clients, the package includes: Reauthorization of the Export-Import Bank for seven years Reauthorization of Brand USA through 2027 A requirement that HUD issue guidelines for including manufactured housing in community plans for housing affordability and community development, as described in S. 1804 Retroactive renewal of the $1-per-gallon biodiesel tax credit, with extension through 2022 House approves USMCA Yesterday the House of Representatives voted 385-41 for legislation to implement the US- Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). -

Cain's Criminal Past

RESEARCH DOSSIER JASON CAIN (NORTH CAROLINA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES: HD-51) Last Updated: March 5, 2020 Paid For By The Republican State Leadership Committee. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ 2 EXECUTIVE SYNOPSIS .............................................................................................................. 5 DOSSIER NOTES ...................................................................................................................... 5 MAIN VULNERABILITIES...................................................................................................... 5 Criminal Past ........................................................................................................................... 5 Liberal Agenda........................................................................................................................ 5 TOP HITS ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Criminal .................................................................................................................................. 6 Policy ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Political ................................................................................................................................... 6 BACKGROUND -

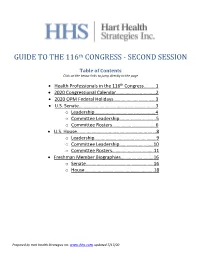

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

Prof Dr. Jan-Hendrik Passoth *11.05.1978, M University Professor

Prof Dr. Jan-Hendrik Passoth *11.05.1978, m University Professor (W3) Sociology of Technology European New School of Digital Studies European University Viadrina Große Scharrnstraße 59 15230 Frankfurt (Oder) +49 (0)335 5534 16 6780 [email protected] University training and degree Publications - Sociology, Computer science, Political Science a) Publications with Scientific Quality Assurance (1998-2003), University of Hamburg, Magister Ar- Books tium, (Max Miller) I. Mämecke, T., Passoth, J.-H., & Wehner, J. (Eds.). - Philosophy, Political Science, Linguistics (1996- (2017). Bedeutende Daten. Modelle, Verfahren und 1998), Extra-mural Student at the Distant Teaching Praxis der Vermessung und Verdatung im Netz. University (Fernuniversität) Hagen in parallel to fin- Wiesbaden: Springer VS. ishing Abitur and community service II. Passoth, J.-H., Peuker, B., & Schillmeier, M. (Eds.). (2012). Agency without Actors? New Ap- Advanced Academic Qualifications proaches to Collective Action. London, UK: Rout- - Habilitation: Sociology, European-University Vi- ledge. adrina Frankfurt (Oder), 2017, Andreas Reckwitz III. Passoth, J.-H. (2008). Technik und Gesellschaft. - Doctorate: Sociology, University of Hamburg, 2007, Sozialwissenschaftliche Techniktheorien und die Max Miller Transformationen der Moderne. Wiesbaden: VS Ver- lag für Sozialwissenschaften. Postgraduate professional career Journal Articles Since 2020: Professor of Sociology of Technology, IV. Mendez, D. & Passoth (2019). Empirical Software ENS, European University Viadrina, FFO Engineering. From Discipline to Interdiscipline. Jour- 2015-2020 Research Group Leader, MCTS, Tech- nal of Systems and Software, 148, 170-179. nische Universität München V. Pollozek, S., & Passoth, J.H. (2019). Infrastructur- - 2017-2018: Professor for Sociology of Technology ing European Migration and Border Control. The Lo- (“Vertretungsprofessur”), Faculty of Arts and Humani- gistics of Registration and Identification at Moria ties, University of Passau Hotspot. -

Final Report EXC16 Non-Confidential

Excellence Initiative / Exzellenzinitiative Final Report / Abschlussbericht Cluster of Excellence / Exzellenzcluster Cultural Foundations of Social Integration Kulturelle Grundlagen von Integration EXC 16 Host University: University of Konstanz DFG ProJect Number: 24060127 First Funding Period: 1st November 2006 – 31st October 2012 Second Funding Period: 1st November 2012 – 31st October 2019 2 Final Report for Cluster of Excellence Cultural Foundations of Social Integration Kulturelle Grundlagen von Integration EXC 16 Host university: University of Konstanz Rector of the host university Coordinator of the Cluster Prof. Dr. Kerstin Krieglstein Prof. Dr. Rudolf Schlögl Signature Signature 3 Contents 1 General Information ............................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Summary ........................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Key data ............................................................................................................................ 7 1.2.1 Host, speaker and other participating institutions ...................................................... 7 1.2.2 Overview of the Cluster’s structure ............................................................................ 7 2 Research ................................................................................................................................. 8 2.1 Premises and forms of research .......................................................................................