Dead Man Walking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications Summer 1996 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Roberta M. Harding University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Repository Citation Harding, Roberta M., "Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment" (1996). Law Faculty Scholarly Articles. 563. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Notes/Citation Information Robert M. Harding, Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment, 30 U.S.F. L. Rev. 1167 (1996). This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment By ROBERTA M. HARDING* FILMMAKING HAS EXISTED since the late 1890s. 1 Capital punish- ment has existed even longer.2 With more than 3,000 individuals lan- guishing on the nation's death rows3 and more than 300 executions occurring since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976,4 capital pun- ishment has become one of modem society's most controversial issues. The cinematic world has not been immune from this debate. -

Transforming Times As Sisters of St

Spring/Summer y Vol. 3 y no. 1 ONEThe CongregaTion of The SiSTerS of ST. JoSeph imagine Transforming Times as Sisters of St. Joseph flows from the purpose for which the congregation exists: We live and work that all people may be united with god and with one another. We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, living out of our common Spring/Summer 2011 y Vol. 3 y no. 1 tradition, witness to God’s love transforming us and our world. Recognizing that we are called to incarnate our mission and imagineONE is published twice yearly, charism in our world in fidelity to God’s call in the Gospel, we in Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter, commit ourselves to these Generous Promises through 2013. by the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph. z We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, promise to take the risk CENTRAL OFFICE to surrender our lives and resources to work for specific 3430 Rocky River Drive systemic change in collaboration with others so that the Cleveland, OH 44111-2997 Ourhungers mission of the world might be fed. (216) 252-0440 WITH SIGNIFICANT PRESENCE IN z We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, promise to recognize the reality that Earth is dying, to claim our oneness with Baton Rouge, LA Earth and to take steps now to strengthen, heal and renew Cincinnati, OH Crookston, MN the face of Earth. Detroit, MI z Kyoto, Japan We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, promise to network LaGrange Park, IL with others across the world to bring about a shift in the Minneapolis-St. -

And Then One Night… the Making of DEAD MAN WALKING

And Then One Night… The Making of DEAD MAN WALKING Complete program transcript Prologue: Sister Helen and Joe Confession scene. SISTER HELEN I got an invitation to write to somebody on death row and then I walked with him to the electric chair on the night of April the fifth, 1984. And once your boat gets in those waters, then I became a witness. Louisiana TV footage of Sister Helen at Hope House NARRATION: “Dead Man Walking” follows the journey of a Louisiana nun, Sister Helen Prejean, to the heart of the death penalty controversy. We see Sister Helen visiting with prisoners at Angola. NARRATION: Her groundbreaking work with death row inmates inspired her to write a book she called “Dead Man Walking.” Her story inspired a powerful feature film… Clip of the film: Dead Man Walking NARRATION: …and now, an opera…. Clip from the opera “Dead Man Walking” SISTER HELEN I never dreamed I was going to get with death row inmates. I got involved with poor people and then learned there was a direct track from being poor in this country and going to prison and going to death row. NARRATION: As the opera began to take shape, the death penalty debate claimed center stage in the news. Gov. George Ryan, IL: I now favor a moratorium because I have grave concerns about our state’s shameful record of convicting innocent people and putting them on death row. Gov. George W. Bush, TX: I’ve been asked this question a lot ever since Governor Ryan declared a moratorium in Illinois. -

The Journey of Dead Man Walking

Sacred Heart University Review Volume 20 Issue 1 Sacred Heart University Review, Volume XX, Article 1 Numbers 1 & 2, Fall 1999/ Spring 2000 2000 The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Helen Prejean Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview Recommended Citation Prejean, Helen (2000) "The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking," Sacred Heart University Review: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the SHU Press Publications at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sacred Heart University Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Cover Page Footnote This is a lightly edited transcription of the talk delivered by Sister Prejean at Sacred Heart University on October 31, 2000, sponsored by the Hersher Institute for Applied Ethics and by Campus Ministry. This article is available in Sacred Heart University Review: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 Prejean: The Journey of Dead Man Walking SISTER HELEN PREJEAN, C.S.J. The Journey of Dead Man Walking I'm glad to be with you. I'm going to bring you with me on a journey, an incredible journey, really. I never thought I was going to get involved in these things, never thought I would accompany people on death row and witness the execution of five human beings, never thought I would be meeting with murder victims' families and accompanying them down the terrible trail of tears and grief and seeking of healing and wholeness, never thought I would encounter politicians, never thought I would be getting on airplanes and coming now for close to fourteen years to talk to people about the death penalty. -

An Interview with Jake Heggie

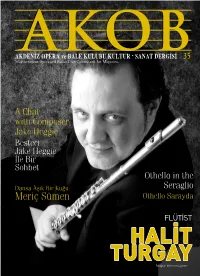

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean. -

Execution Ritual : Media Representations of Execution and the Social Construction of Public Opinion Regarding the Death Penalty

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2011 Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty. Emilie Dyer 1987- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Dyer, Emilie 1987-, "Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 388. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/388 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXECUTION RITUAL: MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fullfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May, 2011 -------------------------------------------------------------- EXECUTION RITUAL : MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Brook Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Approved on April 11, 2011 by the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director (Dr. -

HELEN PREJEAN People of God Remarkable Lives, Heroes of Faith

HELEN PREJEAN People of God Remarkable Lives, Heroes of Faith People of God is a series of inspiring biographies for the general reader. Each volume offers a compelling and honest narrative of the life of an important twentieth- or twenty- first-century Catholic. Some living and some now deceased, each of these women and men has known challenges and weaknesses familiar to most of us but responded to them in ways that call us to our own forms of heroism. Each of- fers a credible and concrete witness of faith, hope, and love to people of our own day. John XXIII Massimo Faggioli Oscar Romero Kevin Clarke Thomas Merton Michael W. Higgins Francis Michael Collins Flannery O’Connor Angela O’Donnell Martin Sheen Rose Pacatte Jean Vanier Michael W. Higgins Dorothy Day Patrick Jordan Luis Antonio Tagle Cindy Wooden Georges and Pauline Vanier Mary Francis Coady Joseph Bernardin Steven P. Millies Corita Kent Rose Pacatte Daniel Rudd Gary B. Agee Helen Prejean Joyce Duriga Paul VI Michael Collins Elizabeth Johnson Heidi Schlumpf Thea Bowman Maurice J. Nutt Shahbaz Bhatti John L. Allen Jr. More titles to follow. Helen Prejean Death Row’s Nun Joyce Duriga LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Cover design by Red+Company. Cover illustration by Philip Bannister. © 2017 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. -

Oral History Center University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Frederica Von Stade Frederica Von Stade

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Frederica von Stade Frederica von Stade: American Star Mezzo-Soprano Interviews conducted by Caroline Crawford in 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015 Copyright © 2020 by The Regents of the University of California Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Frederica von Stade dated February 2, 2012. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

The Death Penalty

2 CASE STUDY 1 NARRATIVE SHIFT AND THE DEATH PENALTY In this case study, The Opportunity Agenda explores a narrative shift that transpired over a period of almost 50 years—from 1972, a time when the death penalty was widely supported by the American public, to the present, a time of growing concern about its application and a significant drop in support. It tells the story of how a small, under-resourced group of death penalty abolitionists came together and developed a communications strategy designed to raise doubts in people’s minds about the system’s fairness that would cause them to reconsider their views. In its early days, the abolition movement was composed of civil liberties and civil rights organizations, death pen- alty litigators, academics, and religious groups and individuals. Later, new and influential voices joined who were directly impacted by the death penalty, including family members of murder victims and death row exonerees. Key players used a combination of tactics, including coalition building—which brought together litigators and grass- roots organizers—protests and conferences, data collection, storage, and dissemination, original research fol- lowed by strategic media placements, and original public opinion research. This case study highlights the importance of several factors necessary in bringing about narrative shift. Key find- ings include: It can be a long haul. In the case of issues like the death penalty, with its heavy symbolic and racialized 1. associations, change happens incrementally, and patience and persistence on the part of advocates are critical. Research matters. Although limited to a few focus groups, the public opinion research undertaken in 2. -

Script of Dead Man Walking

Dead Man Walking Phil. 321: Social Ethics Lawrence M. Hinman, Ph.D. University of San Diego Internet Movie Database Script Source: http://www.script-o-rama.com/movie_scripts/d/dead-man-walking-script- transcript.html Dead Man Walking Script - Dialogue Transcript Voila! Finally, the Dead Man Walking script is here for all you quotes spouting fans of the movie directed by Tim Robbins and starring Susan Sarandon as Helen Prejean and Sean Penn. This script is a transcript that was painstakingly transcribed using the screenplay and/or viewings of Dead Man Walking. I'll be eternally tweaking it, so if you have any corrections, feel free to drop me a line. You won't hurt my feelings. Honest. Swing on back to Drew's Script-O-Rama afterwards for more free scripts! Dead Man Walking Script -Hi, Sister. -Hi, Billie Jean. How you doing? It’s the late Sister Helen. l've got a note from my mama, ldella. Do you need a new notebook? -Thanks. -How about you, Melvin? The resident council wants us at their meeting tomorrow. -Can you be there at 7:00? -Yes. -New poetry books. -Your poem got all smudged. Smudged? Sister Helen, l got another letter from that guy. -Which guy is that, Luis? -Angola inmate, death row. -Oh, yeah. -Could you write to him? Sounds like he could use some friendly words. -l'll come up after the class. -Okay. -lt got smudged. -You can still read it. ''There's a woman standing there in the dark. And she's got big arms to hold you. -

Dead Man Walking Tells the Story of Sister Helen Prejean, Who Establishes a Special Relationship with Matthew Poncelet, a Prisoner on Death Row

Dead Man Walking tells the story of Sister Helen Prejean, who establishes a special relationship with Matthew Poncelet, a prisoner on death row. Matthew Poncelet has been in prison six years, awaiting his execution by lethal injection for killing a teenage couple. He committed the crime in company with Carl Vitello, who received life imprisonment as a result of being able to afford a better lawyer. The film consolidates two different people (Elmo Patrick Sonnier and Robert Lee Willie) whom Prejean counseled on death row into one character, as well as merging Prejean in Cambridge, Mass. in Sept. 2000 their crimes and their victims' families into one event. In 1981, she started working with convicted murderer Elmo Patrick Sonnier, who was sentenced to death by electrocution. Sonnier had received a sentence of death in April 1978 for the November 5, 1977 rape and murder of Loretta Ann Bourque, 18, and the murder of David LeBlanc, 17. He was executed in 1984. The account is based on the inmate Robert Lee Willie who, with his friend Joseph Jesse Vaccaro, raped and killed 18- year-old Faith Hathaway in May 1980, eight days later kidnapping a couple from a wooded lovers' lane, raping the 16-year-old girl, Debbie Morris, and then stabbing and shooting her boyfriend, 20-year-old Mark Brewster, leaving him tied to a tree paralyzed from the waist down. Willie was executed in 1984. She has been the spiritual adviser to several convicted murderers in Louisiana, and accompanied them to their electrocutions. St. Anthony Messenger says “you could call her the Mother Teresa of Death Row.” After watching Elmo Patrick Sonnier executed in 1984, she said, “I couldn't watch someone being killed and walk away. -

Sister Helen Prejean

An Evening with Sister Helen Prejean Author of: Thursday, May 24, 2018 Our Lady of the Lake Catholic Church 790 A Avenue, Lake Oswego, OR 97034 5:30 to 6:30 pm: “Dead Man Walking : The Journey Continues” 6:30 to 7:00 pm: Meet Sister Helen/Book Signing 7:00 to 9:00 pm: VIP Dinner with Sr. Helen at Marylhurst University Sr. Helen’s talk in the church is free of charge. A“free will”offering will be gladly accepted. Tickets are available for purchase for the VIP Dinner. Please call : 503-990-7060 / [email protected] www.oadp.org “Mercy is stronger and more God-like than vengeance.” Sister Helen Prejean Photo Credit : Scott Langley Sister Helen Prejean, CSJ Biographical Information Ministry Against the Death Penalty 3009 Grand Route St. John, #6, New Orleans, LA 70119 Ph: 504-948-6557 • Fax: 504-948-6558 • www.sisterhelen.org Sister Helen Prejean has been instrumental in sparking national dialogue on the death penalty and helping to shape the Catholic Church’s newly vigorous opposition to state executions. She travels around the world giving talks about her ministry. She considers herself a southern storyteller. Sister Helen is a member of the Congregation of St. Joseph. She spent her first years with the Sisters teaching religion to junior high school students. Realizing that being on the side of poor people is an essential part of the Gospel, she moved into the St.Thomas Housing Project in New Orleans and began working at Hope House from 1981-1984. During this time, she was asked to correspond with death row inmate Patrick Sonnier at Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola.