The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (Incorporating Man)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol.4 No.2 ISSN 2518-3966

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture (LLC) June 2017 edition Vol.4 No.2 ISSN 2518-3966 International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture (LLC) 2017 / June Publisher: European Scientific Institute, ESI Reviewed by the “International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture” editorial board 2017 June 2017 edition vol. 4, no. 2 The contents of this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinion or position of the European Scientific Institute. Neither the European Scientific Institute nor any person acting on its behalf is responsible for the use which may be made of the information in this publication. ISSN 2518-3966 International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture (LLC) June 2017 edition Vol.4 No.2 ISSN 2410-6577 About The Journal The “International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture” (LLC) is a peer reviewed journal which accepts high quality research articles. It is a quarterly published international journal and is available to all researchers who are interested in publishing their scientific achievements. We welcome submissions focusing on theories, methods and applications in Linguistics, Literature and Culture, both articles and book reviews. All articles must be in English. Authors can publish their articles after a review by our editorial board. Our mission is to provide greater and faster flow of the newest scientific thought. LLC’s role is to be a kind of a bridge between the researchers around the world. “LLC” is opened to any researchers, regardless of their geographical origin, race, nationality, religion or gender as long as they have an adequate scientific paper in the educational sciences field. -

The Explorations and Poetic Avenues of Nikos Kavvadias

THE EXPLORATIONS AND POETIC AVENUES OF NIKOS KAVVADIAS IAKOVOS MENELAOU * ABSTRACT. This paper analyses some of the influences in Nikos Kavvadias’ (1910-1975) poetry. In particular – and without suggesting that such topic in Kavvadias’ poetry ends here – we will examine the influences of the French poet Charles Baudelaire and the English poet John Mase- field. Kavvadias is perhaps a sui generis case in Modern Greek literature, with a very distinct writing style. Although other Greek poets also wrote about the sea and their experiences during their travelling, Kavvadias’ references and descriptions of exotic ports, exotic women and cor- rupt elements introduce the reader into another world and dimension: the world of the sailor, where the fantasy element not only exists, but excites the reader’s imagination. Although the world which Kavvadias depicts is a mixture of fantasy with reality—and maybe an exaggerated version of the sailor’s life, the adventures which he describes in his poems derive from the ca- pacity of the poetic ego as a sailor and a passionate traveller. Without suggesting that Kavvadias wrote some sort of diary-poetry or that his poetry is clearly biographical, his poems should be seen in connection with his capacity as a sailor, and possibly the different stories he read or heard during his journeys. Kavvadias was familiar with Greek poetry and tradition, nonetheless in this article we focus on influences from non-Greek poets, which together with the descriptions of his distant journeys make Kavvadias’ poems what they are: exotic and fascinating narratives in verse. KEY WORDS: Kavvadias, Baudelaire, Masefield, comparative poetry Introduction From an early age to the end of his life, Kavvadias worked as a sailor, which is precisely why it can be argued that his poetry had been inspired by his numerous travels around the world. -

2020 Menelaou Iakovos 13556

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Reading Cavafy through the medical humanities illness, disease and death Menelaou, Iakovos Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 1 | P a g e Reading Cavafy through the Medical Humanities: Illness, Disease and Death By Iakovos Menelaou King’s College London, 2019 2 | P a g e Abstract: This thesis seeks to break new ground in Modern Greek studies and the medical humanities. -

1 CURRICULUM VITAE CHRYSOSTOMOS (TOM) KOSTOPOULOS Department of Classics Turlington Hall 3328 Center for Greek Studies

CURRICULUM VITAE CHRYSOSTOMOS (TOM) KOSTOPOULOS Department of Classics Turlington Hall 3328 Center for Greek Studies POB 117435 / Dauer 125 Center for EU Studies University of Florida University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611 PERSONAL INFORMATION: • Greek Citizen, US Citizen EMPLOYMENT: • 2003-present: Lecturer, Department of Classics, (Jointed Appointment, Center for European Studies, Center for Greek Studies), University of Florida • 2012-2013: Macricostas Visiting Endowed Chair of Hellenic and Modern Greek Studies, Western Connecticut State University • 1997-2003: Instructor-Teaching Assistant, Department of Classics, University of Wisconsin EDUCATION: • 2004 Ph.D. Classics, University of Wisconsin-Madison Dissertation: The Stars and the Emperors: Astrology and Politics in the Roman World, directed by James C. McKeown Committee Members: Barry B. Powell, Victoria Pagan, Andrew Wolpert, Marc Kleijwegt • 1998 M.A. Classics, University of Wisconsin-Madison • 1995 B.A. Classical Philology, University of Ioannina-Greece RESEARCH INTERESTS: • Roman and Ancient Greek Science (Ancient Astronomy and Astrology in particular) • Modern Greek Politics and Society, Modern Greek History, National Identity and the European Union LANGUAGES: Modern Greek (native speaker), Ancient Greek, Latin, German (comprehensive reading), French (comprehensive reading) PUBLICATIONS: 1 • “Roman Portable Sundials: The Empire in your Hand” (book review), Mouseion Volume 15 No. 1 2018: 162-165 • “Translating Nikos Kavvadias Poetry into English” OLME 90, 2008: 35-48 • “Cheiron in America: Myth and Allegory in the Centaur of John Updike” Omprela 76, 2007: 57-60 PRESENTATIONS AND CONFERENCE PAPERS: • October 2017: “A Greek Tragedy in the Making? Explaining Greece's Debt Crisis,” Oak Hammock, Gainesville FL • February 2016: “A Greek Tragedy in the Making? The Eurozone vs. -

11Th Annual Capital Link Crew Changes in the COVID-19

A SEMI-ANNUAL EDITION OF DANAOS SHIPPING CO. LTD. ISSUE #19, JULY 2020 Crew Changes in the COVID-19 Era The ongoing outbreak of coronavirus dis- port but the flights do not always align with ease (COVID-19) that was first detected in the above requirement due to unavailability. Hubei Province, China in December 2019 Moreover, the CBP will approve the flights has now spread across all continents. The for the Offsigners only when the vessel will number of confirmed cases outside of China be alongside the USA port so this practically has surpassed the Chinese total. There was means that the Onsigners will have already a significant impact in crew changes from flown to join the vessel at a USA port and COVID-19 as the majority of ports banned afterwards the Crew department will have the crew changes as a preventive measure the confirmation from CBP that the Offsign- against COVID-19. ers are approved to fly or not. Port authorities will commonly require all Therefore, to prevent any potential problem ships to proactively report any suspect or in USA ports where the Onsigners will have actual illness cases to local health authorities tigate if they have been in an affected area already joined the vessel and the Offisgners after arrival. In some countries, ships’ Mas- within the previous 14 days. will be banned from the CBP to sign off the ters may also be required to complete a spe- On the 22nd of June 2020 onboard Danaos vessel, the Crew department always takes cial questionnaire tailored to the COVID-19 vessels there were 235 Officers and 283 Rat- into consideration the summary of the On- outbreak, typically with questions concern- ings with expired contracts who need to be signers and Offsigners in a crew change not ing Crews and passengers recent travel itin- replaced as soon as possible. -

Behrakis' Fulfilling Hellenic Experience Father Beaten to Death

S o C V th ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ E 10 0 ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald anniversa ry N www.thenationalherald.com A weekly Greek-AmericAn PublicAtion 1915-2015 VOL. 19, ISSUE 957 February 13-19 , 2016 c v $1.50 Behrakis’ Father Beaten1 to Death Fulfilling By Son, Who Claims it Hellenic Was in Self-Defense Experience TNH Staff friendly terms with his ex, the News reported, Safetis jumped FLUSHING – Ioannis Safetis, a into his car and headed to her Philanthropist Goes 57-year-old Queens resident house, where he threatened all was beaten to death, allegedly of them. To Homeland for by his son Demetrios, 19, Friday Safetis then ran to his car to night February 6, outside the grab a steering wheel lock club, Honorary Degree home of the elder Safetis’ ex- which he brought back to the girlfriend, in the Auburndale house and started waving By Theodore Kalmoukos neighborhood of Flushing. around. Demetrios wrestled the Demetrios was charged with club away from his father and BOSTON, MA – George D. manslaughter, assault ,and crim - beat him to death with it, the Behrakis, acclaimed community inal possession of a weapon News reported. leader, businessman, philan - when he was arraigned in Safetis lay unresponsive on thropist, church man, family Queens Criminal Court. Judge the ground with a big wound man, and a proud Hellene, from William Harrington set bail at on his head. He was taken to the historic city of Lowell, MA , $50,000 and Safetis returns to New York Presbyterian Hospital spoke with TNH spoke at length court on February. -

![Curriculum Vitæ Panagiotis Christias [En Français]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7844/curriculum-vit%C3%A6-panagiotis-christias-en-fran%C3%A7ais-6957844.webp)

Curriculum Vitæ Panagiotis Christias [En Français]

Panagiotis Christias curriculum vitæ Panagiotis Christias [en français] March 2021 UNIVERSITY OF CYPRUS Nicosia, Cyprus 1 Panagiotis Christias Curriculum Vitæ TABLE DES MATIÈRES DONNÉES PERSONNELLES ................................................................................................................................ 1 I/ PROFIL ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 II/ CURSUS .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 III/ FONCTIONS ANTÉRIEURES............................................................................................................... 5 IV/ PUBLICATIONS ....................................................................................................................................10 V/ COMMUNICATIONS .................................................................................................................................17 VI/ DIRECTION DE TRAVAUX................................................................................................................27 VII/ JURYS DE THÈSE .................................................................................................................................29 VIII/ BOURSES - DISTINCTIONS ..............................................................................................................29 TABLE DES MATIÈRES......................................................................................................................................29 -

Newsletter – Spring 2019

Newsletter – Spring 2019 “Spring is the time of plans and projects” Leo Tolstoy Contents Editorial 3 Thoughts Now what? Life after the European Year of Cultural Heritage 4 IE activities Join us in Sarajevo! 7 Training The first CIP course 9 A view of the world using heritage interpretation to navigate 11 The phenomena of Elefsina revealed by interpreters 13 CIG in the small Croatian city of Kastav 14 Guides have to make us feel emotion and taste tradition 16 Congratulations to our newly certified members 18 Upcoming courses and webinars 19 IE member activities Tourist Guide – a power that destroys cultural differences 20 What’s going on elsewhere IntoAlbania: A new perspective on Albania 22 BE MUSEUMER 25 Research 27 Funding 27 IE announcements Welcome to our new members 28 We search for an experienced organiser in media production 30 Welcoming members to the IE office 31 General Assembly – Call for agenda items 33 Our newsletters need you! Further announcements 34 Upcoming events in Europe 36 And finally... Cover image: Magnolia flowers (Photo: Banks) 2 Editorial IE Management Dear members, Hard to believe that some weeks ago, up to three metres of snow covered parts of Central Europe. How good to know that IE wasn’t completely frozen. While the first heralds of spring were desperately sought in our Facebook group, eight IE training courses have already taken place in the Mediterranean. This was our quickest start to the ‘training season’ so far. To read the enthusiastic feedback from so many members improving their interpretive skills helped to overcome the hardships of winter, even for those who had to be a bit more patient. -

TOGETHER for the Environment CONTENTS

7-8 2021 • Issue 76 THE WORLD OF ALPHA BANK TOGETHER for the environment CONTENTS IN FOCUS p. 3 Τ We successfully concluded the 2021 EU-wide Stress Test p. 9 “Project Skyline”: Alpha Bank strengthens its position in the real estate sector p. 11 Ordinary General Meeting of the Shareholders of Alpha Services and Holdings p. 12 Alpha Bank named “Best Bank in Greece” for 2021 by the international financial publication “Euromoney” p. 13 Serial Publication CEO Vassilis Psaltis at an online event of SEV: “Alpha Bank assumes the responsibility to support the Greek economy's leap to Tomorrow” p. 14 Group Personnel Alpha Bank: Gold Sponsor of the 2nd International Conference of the Perrotis College “Krinos” Olive Center p. 17 7-8 2021 • Issue 76 Meet the Agile Bankers… p. 18 The “pre-accelerator” stage of the i3 competition has been successfully completed! p. 22 INNOVATORS p. 26 CULTURE Orestis Kanellis p. 29 Publication offer by Alpha Bank p. 31 The J.F. Costopoulos Foundation p. 32 Editor: CORPORATE COMMUNICATIONS DIVISION PRODUCTS AND SERVICES Corporate Identity and Group Serial Publications Freedom Pass for young people aged 18-25 who choose to be vaccinated against Covid-19 p. 36 p. 37 Editing: Eleftheria Athanasopoulou “The Bonus Summer has arrived!” p. 37 40, Stadiou Str. Keeping the limit of contactless transactions without using a PIN at Euro 50 102 52 ATHENS, GREECE Alpha Bank participating in actions in partnership with government agencies p. 38 Τ E-mail: [email protected] “Alpha Photovoltaic” for Small Businesses p. 40 Design - Production: GOD A.E. -

PDF File, 2.01 MB

STIMULUS AND CREATIVE RESPONSE (1880-1930) GRIGORIOS XENOPOULOS KONSTANTINOS THEOTOKIS It may be that the first novels of Grigorios Xenopoulos (1867- Born into the Corfu aristocracy in 1872, Konstantinos Theotokis 1951), represent a minority ‘opposition’ to the dominant folkloric studied in Graz and died at the age of 51 in 1923. His greatest realism of the time, and should be seen as the neglected forerunners influence was the Russian novel and he became a committed of an urban tradition that only came fully into its own in the first socialist. His prose writing was deeply social in orientation, and decade of the twentieth century. On the other hand, the (justified) with narratives such as The Life and Death of the ‘Hangman’ excitement at the rediscovery and reassessment of these neglected (1920) he treats themes such as the obsession with private texts should not obscure the adherence of most of them to the dom- ownership and the love of profit and money. Theotokis was a inant ‘folkloric’ model of the period, as that was defined above. The skilled anatomist of the great class divisions and conflicts of his focus in them is frequently on a community rather than on an in- time. His prose is grounded in passion and romanticism, but his dividual, and descriptive details of setting and social behaviour are contact with socialism and its theoretical underpinnings resulted no less prominent than in the rural ethography of the time. It would in an abiding interest in direct social experience, which he sought not be unreasonable to suggest, then, that the urban fiction of the to present through human conflicts, often so intense that they lead last two decades of the nineteenth century gives a distinctive ‘twist’ to disaster. -

The Greek Lorca: Translation, Homage, Image

The Greek Lorca: Translation, Homage, Image ANNA ROSENBERG ARAID researcher, Universidad de Zaragoza Abstract Greece is a case particularly worthy of attention within the panorama of Federico García Lorca’s worldwide reception. In comparison to other countries, Lorca’s pres- ence in Greece has remained uninterrupted since his first appearance and remains current, with new translations, rewritings, adaptations, and stagings of his plays continually being produced. Lorca has also spurred a wide range of creative responses inspired by his life and death such as essays, music, poetry, and dramas. He has also stimulated debates over aesthetic, literary, cultural, ideological and political issues, and has thus become indissolubly bound to the Greek cultural environment both as a Greek and a Spanish icon. This paper examines the ways Lorca has been received and treated in Greece in relation to the cultural and historical context. Resumen Grecia es un caso que merece particular atención dentro del panorama de la recep- ción internacional de Federico García Lorca. En comparación con otros países, la presencia de Lorca en Grecia ha permanecido ininterrumpida desde su primera aparición y se mantiene viva con nuevas traducciones, versiones, adaptaciones y puestas en escena de sus obras, producidas continuamente. Lorca ha provocado una gran variedad de respuestas creativas inspiradas por su vida y muerte, como ensayos, música, poesía y obras teatrales. También ha estimulado debates sobre temas estéticos, literarios, culturales, ideológicos y políticos, y así se ha vinculado de manera indisoluble con el contexto cultural griego como un ícono griego y español a la vez. Este artículo investiga la manera en la que Lorca ha sido recibido y tratado en Grecia dentro de un contexto histórico y cultural. -

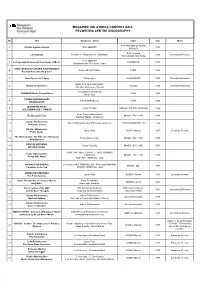

Discography Update 02 June 21-ENG-Edit NESP

MEGARON THE ATHENS CONCERT HALL RECORDING CENTRE DISCOGRAPHY No Title Composer - Artist Label Year Notes THE FRIENDS OF MUSIC 1 Dimitris Sgouros Recital W.A. MOZART 1991 SOCIETY BMG Classics 2 La Camerata Beethoven - Shostakovich - Skalkottas 1993 International Release RCA VICTOR RED SEAL W.A. MOZART 3 La Camerata Orchestra of the Friends of Music EUROBANK 1993 Symphonies No 34 & 36 in C major SHOSTAKOVICH SCRIABIN RACHMANINOV 4 Annie and Lola Totsiou LYRA 1995 Russian Music for two pianos 5 David Lynch / Lit'l Song David Lynch FM RECORDS 1995 International Release NIKOLAUS HARNONCOURT 6 Beethoven Overtures TELDEC 1996 International Release Chamber Orchestra of Europe Christophoros Stamboglis 7 CHAMBER Music Compositions LYRA 1996 Danae Kara YANNIS MARKOPOULOS 8 Yannis Markopoulos LYRA 1996 RENAISSANCE JEANNETTE PILOU 9 Jeannette Pilou SERIOS LIVE RECORDINGS 1996 LES CHEMINS DE L' AMOUR Music Thanos Mikroutsikos 10 The Blue Line Tales ΜΙΝΟS - EMI / HMV 1996 Narration Mania Tehritzoglou Athens Philharmonia 11 Athens Municipality New Philarmonic Orchestra ATHENS MUNICIPALITY 1996 Christmas Carols Dimitris Mitropoulos 12 Danae Kara AGORA Musica 1997 European Release Piano Works The Story of Lulu, The Tale of Le Bourgeois 13 Thanos Mikroutsikos ΜΙΝΟS - EMI / HMV 1997 Gentilhomme KOSTAS KOTSIOLIS 14 Kostas Kotsiolis ΜΙΝΟS - EMI / HMV 1997 Moonlight Guitar CONSTANTINE P. CAVAFY - CHRISTOFOROS Thanos Mikroutsikos 15 LIONTAKIS ΜΙΝΟS - EMI / HMV 1997 Poetry with Music KOSTAS THOMAIDIS, song MICHALIS GRIGORIOU Poems by TAKIS SINOPOULOS - ARIS ALEXANDROU