The Nonconformist Movement in Industrial Swansea, 1780-1914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bread and Butter Actions to Solve Poverty Listening to People 2Nd

Spring 2019 Wales’ best policy and politics magazine Bread and butter actions to solve poverty Mark Drakeford AM Listening to people Suzy Davies AM 2nd home tax loophole Siân Gwenllian AM ISSN 2059-8416 Print ISSN 2398-2063 Online CONTENTS: SPRING 2019 Wales’ best policy and politics magazine 50.open.ac.uk A unique space in the heart of Cardiff for everything connected with your wellbeing. 50 MLYNEDD O 50 YEARS OF Created by Gofal, the charity thinking differently about YSBRYDOLIAETH INSPIRATION mental health. Wedi’i seilio ar ei chred gadarn sef y dylai addysg fod yn Dedicated Workplace Wellbeing Programmes agored i bawb, mae’r Brifysgol Agored wedi treulio’r hanner A team of professional counsellors with a range of approaches canrif ddiwethaf yn helpu dysgwyr ledled Cymru a’r byd i droi’r Employee Assistant Programmes offering quality support amhosibl yn bosibl. Yn ystod carreg filltir ein pen-blwydd yn 50 oed, rydym yn creu rhaglen o ddigwyddiadau a gweithgareddau cyrous a fydd yn All profits will be reinvested into Gofal - amlygu’r myfyrwyr, sta, partneriaid a theulu’r Brifysgol sustainable wellbeing for all Agored sydd wedi gwneud ein sefydliad yr hyn ydyw heddiw. Mark Drakeford AM Alicja Zalesinska Alun Michael Company Number: 2546880 2 Solving poverty in Wales 10 Housing is a human right 18 The challenge of austerity Registered in England and Wales Registered Charity Number: 1000889 Founded on the firm belief that education should be open to to policing all, The Open University has spent the past fifty years helping learners from all over Wales and the world to make the impossible possible. -

36 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

36 bus time schedule & line map 36 Swansea City Centre - Morriston View In Website Mode The 36 bus line (Swansea City Centre - Morriston) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Morriston: 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM (2) Swansea: 6:32 AM - 9:52 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 36 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 36 bus arriving. Direction: Morriston 36 bus Time Schedule 28 stops Morriston Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:50 AM - 10:50 PM Monday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM Bus Station J, Swansea Tuesday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM St Mary`S Church B, Swansea Saint Mary's Square, Swansea Wednesday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM High Street 1, Swansea Thursday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM 5-6 High Street, Swansea Friday 6:42 AM - 10:50 PM High Street Station, Swansea Saturday 8:50 AM - 10:50 PM Dyfatty, Hafod 143-144 High Street, Swansea Zoar Chapel, Waun Wen 36 bus Info Carmarthen Road, Swansea Direction: Morriston Stops: 28 Waun Wen Inn, Waun Wen Trip Duration: 37 min Line Summary: Bus Station J, Swansea, St Mary`S Cwmfelin Club, Cwmbwrla Church B, Swansea, High Street 1, Swansea, High Mansel Terrace, Swansea Street Station, Swansea, Dyfatty, Hafod, Zoar Chapel, Waun Wen, Waun Wen Inn, Waun Wen, Robert Street, Brondeg Cwmfelin Club, Cwmbwrla, Robert Street, Brondeg, Richard Street, Swansea Elgin Street East, Brondeg, Manselton Hotel, Manselton, Brynhyfryd Square, Manselton, Parkhill Elgin Street East, Brondeg Road, Penƒlia, Community Centre, Treboeth, Visteon 103 Manselton Road, Swansea Club, Tirdeunaw, Caersalem Cross, -

Daniel Evans

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Daniel Evans Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer COMPANY Robert Jonathan Munby Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE PRIDE Oliver Richard Wilson Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE ART OF NEWS Dominic Muldowney London Sinfonietta SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Tony Award Nomination for Best Performance by a Lead Actor in a Musical 2008 George Sam Buntrock Studio 54 Outer Critics' Circle Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical 2008 Drama League Awards Nomination for Distinguished Performance 2008 GOOD THING GOING Part of a Revue Julia McKenzie Cadogan Hall Ltd SWEENEY TODD Tobias Ragg David Freeman Southbank Centre TOTAL ECLIPSE Paul Verlaine Paul Miller Menier Chocolate Factory SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Wyndham's Theatre/Menier George Sam Buntrock Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical 2007 Chocolate Factory GRAND HOTEL Otto Michael Grandage Donmar Warehouse CLOUD NINE Betty/Edward Anna Mackmin Crucible Theatre CYMBELINE Posthumous Dominic Cooke RSC MEASURE FOR MEASURE Angelo Sean Holmes RSC THE TEMPEST Ariel Michael Grandage Sheffield Crucible/Old Vic Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in Ghosts) GHOSTS Osvald Steve Unwin English Touring Theatre Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in The Tempest) WHERE DO WE LIVE Stephen Richard -

Prayer Diary – July-September 2018

Prayer Diary – July-September 2018 This diary has been compiled to help us pray together for one another and our common concerns. It is also available on the diocesan website www.europe.anglican.org, both for downloading and for viewing. This should be updated as new appointments and other changes are announced. A daily prayer update is sent via Twitter on the diocesan account @DioceseinEurope Each chaplaincy, with the communities it serves, is remembered in prayer once a quarter, following this weekly pattern: • Eastern Archdeaconry: Monday, Saturday • Archdeaconry of France: Tuesday, Saturday • Archdeaconry of Gibraltar: Wednesday, Saturday • Italy & Malta Archdeaconry: Friday • Archdeaconry of North West Europe: Thursday • Swiss Archdeaconry: Friday • Archdeaconry of Germany and Northern Europe • Nordic and Baltic Deanery: Monday • Germany: Saturday On Sundays, we pray for subjects which affect us all (e.g. reconciliation, on Remembrance Sunday), or which have local applications for most of us (e.g. the local cathedral or cathedrals). This will include Diocesan Staff, Churches in Communion and Ecumenical Partners. SUNDAY INTERCESSIONS should, by tradition, include prayer for Bishop Robert and the local Head of State by name. In addition, prayers may also include Bishop David (the Suffragan Bishop) and, among the heads of other states, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and the leaders of other countries represented in the congregation. Sources and resources also commended: Anglican Cycle of Prayer www.anglicancommunion.org/resources/cycle-of-prayer/download-the-acp.aspx World Council of Churches http://www.oikoumene.org/en/resources/prayer-cycle (weekly), Porvoo Cycle http://www.porvoocommunion.org/resources/prayer-diary/ (weekly), and Common Worship Lectionary festivals and commemorations (CW, pp 2-17 or https://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-worship/worship/texts.aspx ). -

Review 2015-16

DIOCESE IN EUROPE THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND R EV IEW 2015-16 europe.anglican.org WELco ME F ro M THE D I oc E S A N S E cr ETA R Y Welcome to the Annual Report Doves released which provides just a glimpse of to mark Waterloo the extraordinary and inspiring range of Christian life, work, worship, witness, growth and development in the diocese F ro M THE B I S H op over 2015 – a reflection on the common life of the Body of Christ. I introduce this review at the end of my first full year as bishop for the Diocese in Europe. We are a Mission-shaped diocese – a network of Christian communities and It is a year that has been deeply challenging. One country – Greece – has been almost congregations serving Anglicans and overwhelmed by the political and economic consequences of debt. Another country – France – has suffered a year framed by terrorism, from Charlie Hebdo to Bataclan. And other English-speaking Christians, nearly every country in the diocese has been affected by the vast movement of peoples working together to build up the that we call ‘the migration crisis’. Kingdom of God across an enormous Against this background our diocese has been working on a strategy that is faithful geographical area. to our historic identity and relevant to current needs. “Walking together in Faith” was Although we have slender resources, formally commended at the Diocesan Synod and endorsed by the Bishop’s Council. It these pages show that we are a vibrant has five points: building up the body of Christ; sharing in the evangelisation of Europe; and lively diocese, keen to grasp some striving for a just society and sustainable environment; working for reconciliation; with of the many mission opportunities proper resources. -

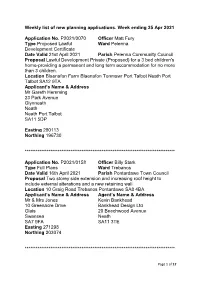

Week Ending 26Th April 2021

Weekly list of new planning applications. Week ending 25 Apr 2021 Application No. P2021/0070 Officer Matt Fury Type Proposed Lawful Ward Pelenna Development Certificate Date Valid 21st April 2021 Parish Pelenna Community Council Proposal Lawful Development Private (Proposed) for a 3 bed children's home-providing a permanent and long term accommodation for no more than 3 children. Location Blaenafon Farm Blaenafon Tonmawr Port Talbot Neath Port Talbot SA12 9TA Applicant’s Name & Address Mr Gareth Hemming 23 Park Avenue Glynneath Neath Neath Port Talbot SA11 5DP Easting 280113 Northing 196730 ********************************************************************************** Application No. P2021/0158 Officer Billy Stark Type Full Plans Ward Trebanos Date Valid 16th April 2021 Parish Pontardawe Town Council Proposal Two storey side extension and increasing roof height to include external alterations and a new retaining wall Location 10 Graig Road Trebanos Pontardawe SA8 4BA Applicant’s Name & Address Agent’s Name & Address Mr & Mrs Jones Kevin Bankhead 10 Greenacre Drive Bankhead Design Ltd Glais 20 Beechwood Avenue Swansea Neath SA7 9FA SA11 3TE Easting 271298 Northing 203074 ********************************************************************************** Page 1 of 12 Application No. P2021/0189 Officer Helen Bowen Type Full Plans Ward Rhos Date Valid 19th April 2021 Parish Cilybebyll Community Council Proposal Extension of agricultural building Location Ty'n Y Cwm Meadows Ty'n Y Cwm Lane Rhos Pontardawe Swansea Neath Port Talbot SA8 3EY Applicant’s Name & Address Mr Rhodri Hopkins Llwynllanc Uchaf Farm Lane From Neath Road To Llwynllanc Uchaf Farm Crynant Neath Neath Port Talbot SA10 8SF Easting 274423 Northing 202360 ********************************************************************************** Application No. P2021/0273 Officer Megan Thomas Type Full Plans Ward Crynant Date Valid 23rd April 2021 Parish Crynant Community Council Proposal The retention and completion of hardstanding for equine care. -

Deaths Taken from Glamorgan Gazette for the Year 1916 Surname First

Deaths taken from Glamorgan Gazette for the year 1916 Surname First Name/s Date of Place of Death Age Cause of Death Other Information Date of Page Col Death Newspaper Abel Mrs. Wife of Willie Abel of 29 17/11/1916 3 6 Fronwen Row, Ogmore Vale Ace Eva 27/04/1916 Southerndown 60 yrs Drowned. Wife of Rees Ace. See also 05/05/1916 2 6 12/05/1916, Pg 2, col 4. Adams Robert 60 yrs Of Victoria Street, 29/12/1916 8 6 Pontycymer Alexander Cyril George 20/02/1916 14 yrs Son of George Alexander of 03/03/1916 8 5 2, Blandy Terrace, Pontycymmer. Buried at Pontycymer Cemetery. Allman William (Pte.) K. I. A. Border Regt. 11/02/1916 8 3 Anderson H. (Pte.) K. I. A. Of Pencoed. Member of the 18/08/1916 5 4 5th South Wales Borderers. Photograph included. Anderson Henry (Pte.) K. I. A. Of Tymerchant. 08/09/1916 2 5 Ap Madoc Wm. America 72 yrs Distinguished Welsh- 15/09/1916 7 5 (Professor) American musician, singer, composer and critic. Native of Maesteg. Arthur John Of Oakland Terrace. 19/05/1916 8 5 Arthur James George 10/07/1916 22 yrs K. I. A. Son of Mr and Mrs A. Arthur, 15/09/1916 3 4 (Bugler) 16 Nantyrychain Terrace, Pontyycymmer. Of the 2nd Rhonddas, 13th Battalion, Welsh Regiment. Ashman William 06/06/1914 In memoriam. Of Ogmore 02/06/1916 4 6 Vale. Ashman Frank (Pte.) K. I. A. Of The Beaches, Pencoed. 11/08/1916 8 2 See also 08/09/1916, Pg 2, Col 5. -

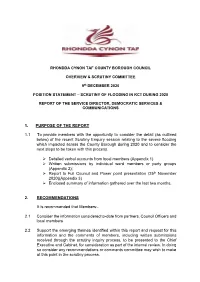

1. PURPOSE of the REPORT 1.1 to Provide Members with The

RHONDDA CYNON TAF COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL OVERVIEW & SCRUTINY COMMITTEE 9th DECEMBER 2020 POSITION STATEMENT – SCRUTINY OF FLOODING IN RCT DURING 2020 REPORT OF THE SERVICE DIRECTOR, DEMOCRATIC SERVICES & COMMUNICATIONS 1. PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 1.1 To provide members with the opportunity to consider the detail (as outlined below) of the recent Scrutiny Enquiry session relating to the severe flooding which impacted across the County Borough during 2020 and to consider the next steps to be taken with this process. Detailed verbal accounts from local members (Appendix 1) Written submissions by individual ward members or party groups (Appendix 2); Report to Full Council and Power point presentation (25th November 2020)(Appendix 3) Enclosed summary of information gathered over the last two months. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS It is recommended that Members:- 2.1 Consider the information considered to-date from partners, Council Officers and local members 2.2 Support the emerging themes identified within this report and request for this information and the comments of members, including written submissions received through the scrutiny inquiry process, to be presented to the Chief Executive and Cabinet, for consideration as part of the internal review. In doing so consider any recommendations or comments committee may wish to make at this point in the scrutiny process. 2.3 Confirm committees request to scrutinise how the Council will respond to the Section 19 statutory report that the Council is required to undertake in respect of the February Floods -

Plu Hydref 2011 Fersiwn

PAPUR BRO LLANGADFAN, LLANERFYL, FOEL, LLANFAIR CAEREINION, ADFA, CEFNCOCH, LLWYDIARTH, LLANGYNYW, CWMGOLAU, DOLANOG, RHIWHIRIAETH, PONTROBERT, MEIFOD, TREFALDWYN A’R TRALLWM. 426 Hydref 2017 60c BRENIN Y BOWLIO LLYWYDDION LLAWEN Ar brynhawn Sul gwlyb yn ddiweddar chwaraewyd twrnamaint bowlio yn Llanfair Caereinion. Er gwaetha’r tywydd roedd y cystadleuwyr yn benderfynol o orffen y gystadleuaeth gan fod y ‘Rose Bowl’ yn wobr mor hynod o dlws i’w hennill. Yn y gêm derfynol roedd Gwyndaf James yn chwarae yn erbyn y g@r profiadol Llun Michael Williams Richard Edwards. Gwyndaf oedd y pencampwr hapus a fo gafodd ei ddwylo ar y ‘Rose Bowl’. Rwan mae Enillwyr y stondin fasnach orau ar faes y Sioe eleni oedd stondin ar y cyd Philip angen dod o hyd i le parchus i arddangos y wobr Edwards, For Farmers a H.V. Bowen. Gwelir Huw, Guto a Rhidian Glyn o For Farm- arbennig hon! ers; Mark Bowen a Philip yn derbyn eu gwobr gan Enid ac Arwel Jones. DWY NAIN FALCH Mae dwy nain falch iawn yn Nyffryn Banw yn dilyn yr Eisteddfod Genedlaethol yn Sir Fôn ym mis Awst. Uchod gwelir Dilys, Nyth y Dryw, Llangadfan gyda’i h@yr Steffan Prys Roberts, Llanuwchllyn a enillodd wobr y Rhuban Glas. Mae Steff yn gweithio i’r Urdd yng Nglanllyn ac yn aelod o Gwmni Theatr Maldwyn, tri chôr a sawl parti canu! Nain arall sy’n byrlymu â balchder yw Marion Owen, Rhiwfelen, Foel sy’n ymfalchïo yn llwyddiant ei hwyres Marged Elin Owen a enillodd Ysgoloriaeth yr Artist Ifanc. Mae Marged bellach wedi cael swydd gyda chwmni castio gwydr y tu allan i Blackpool. -

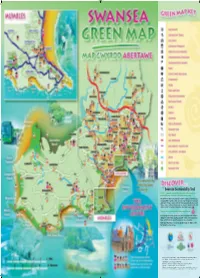

Swansea Sustainability Trail a Trail of Community Projects That Demonstrate Different Aspects of Sustainability in Practical, Interesting and Inspiring Ways

Swansea Sustainability Trail A Trail of community projects that demonstrate different aspects of sustainability in practical, interesting and inspiring ways. The On The Trail Guide contains details of all the locations on the Trail, but is also packed full of useful, realistic and easy steps to help you become more sustainable. Pick up a copy or download it from www.sustainableswansea.net There is also a curriculum based guide for schools to show how visits and activities on the Trail can be an invaluable educational resource. Trail sites are shown on the Green Map using this icon: Special group visits can be organised and supported by Sustainable Swansea staff, and for a limited time, funding is available to help cover transport costs. Please call 01792 480200 or visit the website for more information. Watch out for Trail Blazers; fun and educational activities for children, on the Trail during the school holidays. Reproduced from the Ordnance Survey Digital Map with the permission of the Controller of H.M.S.O. Crown Copyright - City & County of Swansea • Dinas a Sir Abertawe - Licence No. 100023509. 16855-07 CG Designed at Designprint 01792 544200 To receive this information in an alternative format, please contact 01792 480200 Green Map Icons © Modern World Design 1996-2005. All rights reserved. Disclaimer Swansea Environmental Forum makes makes no warranties, expressed or implied, regarding errors or omissions and assumes no legal liability or responsibility related to the use of the information on this map. Energy 21 The Pines Country Club - Treboeth 22 Tir John Civic Amenity Site - St. Thomas 1 Energy Efficiency Advice Centre -13 Craddock Street, Swansea. -

Merthyr Tydfil and the Shropshire Coalfield, 1841-1881

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Female employment in nineteenth-century ironworking districts: Merthyr Tydfil and the Shropshire Coalfield, 1841-1881. Milburn, Amanda Janet Macdonald How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Milburn, Amanda Janet Macdonald (2013) Female employment in nineteenth-century ironworking districts: Merthyr Tydfil and the Shropshire Coalfield, 1841-1881.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42249 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ FEMALE EMPLOYMENT IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY IRONWORKING DISTRICTS: MERTHYR TYDFIL AND THE SHROPSHIRE COALFIELD, 1841-1881 AMANDA JANET MACDONALD MILBURN Submitted to Swansea University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy SWANSEA UNIVERSITY 2013 l i b r a r y ProQuest Number: 10797957 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

FOLK-LORE and FOLK-STORIES of WALES the HISTORY of PEMBROKESHIRE by the Rev

i G-R so I FOLK-LORE AND FOLK-STORIES OF WALES THE HISTORY OF PEMBROKESHIRE By the Rev. JAMES PHILLIPS Demy 8vo», Cloth Gilt, Z2l6 net {by post i2(ii), Pembrokeshire, compared with some of the counties of Wales, has been fortunate in having a very considerable published literature, but as yet no history in moderate compass at a popular price has been issued. The present work will supply the need that has long been felt. WEST IRISH FOLK- TALES S> ROMANCES COLLECTED AND TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION By WILLIAM LARMINIE Crown 8vo., Roxburgh Gilt, lojC net (by post 10(1j). Cloth Gilt,3l6 net {by posi 3lio% In this work the tales were all written down in Irish, word for word, from the dictation of the narrators, whose name^ and localities are in every case given. The translation is closely literal. It is hoped' it will satisfy the most rigid requirements of the scientific Folk-lorist. INDIAN FOLK-TALES BEING SIDELIGHTS ON VILLAGE LIFE IN BILASPORE, CENTRAL PROVINCES By E. M. GORDON Second Edition, rez'ised. Cloth, 1/6 net (by post 1/9). " The Literary World says : A valuable contribution to Indian folk-lore. The volume is full of folk-lore and quaint and curious knowledge, and there is not a superfluous word in it." THE ANTIQUARY AN ILLUSTRATED MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE STUDY OF THE PAST Edited by G. L. APPERSON, I.S.O. Price 6d, Monthly. 6/- per annum postfree, specimen copy sent post free, td. London : Elliot Stock, 62, Paternoster Row, E.C. FOLK-LORE AND FOLK- STORIES OF WALES BY MARIE TREVELYAN Author of "Glimpses of Welsh Life and Character," " From Snowdon to the Sea," " The Land of Arthur," *' Britain's Greatness Foretold," &c.