How Should the Craft of Choreography Be Learned?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Soraya Joins Martha Graham Dance Company and Wild up for the June 19 World Premiere of a Digital Dance Creation

The Soraya Joins Martha Graham Dance Company and Wild Up for the June 19 World Premiere of a Digital Dance Creation Immediate Tragedy Inspired by Martha Graham’s lost solo from 1937, this reimagined version will feature 14 dancers and include new music composed by Wild Up’s Christopher Rountree (New York, NY), May 28, 2020—The ongoing collaboration by three major arts organizations— Martha Graham Dance Company, the Los Angeles-based Wild Up music collective, and The Soraya—will continue June 19 with the premiere of a digital dance inspired by archival remnants of Martha Graham’s Immediate Tragedy, a solo she created in 1937 in response to the Spanish Civil War. Graham created the solo in collaboration with composer Henry Cowell, but it was never filmed and has been considered lost for decades. Drawing on the common experience of today’s immediate tragedy – the global pandemic -- the 22 artists creating the project are collaborating from locations across the U.S. and Europe using a variety of technologies to coordinate movement, music, and digital design. The new digital Immediate Tragedy, commissioned by The Soraya, will premiere online Friday, June 19 at 4pm (Pacific)/7pm (EST) during Fridays at 4 on The Soraya Facebook page, and Saturday, June 20 at 11:30am/2:30pm at the Martha Matinee on the Graham Company’s YouTube Channel. In its new iteration, Immediate Tragedy will feature 14 dancers and 6 musicians each recorded from the safety of their homes. Martha Graham Dance Company’s Artistic Director Janet Eilber, in consultation with Rountree and The Soraya’s Executive Director, Thor Steingraber, suggested the long-distance creative process inspired by a cache of recently rediscovered materials—over 30 photos, musical notations, letters and reviews all relating to the 1937 solo. -

Miss Hill: Making Dance Matter Is Both Gorgeous and Powerful, Crackling with Energy

FIRST RUN FEATURES PRESENTS “Miss Hill: Making Dance Matter is both gorgeous and powerful, crackling with energy. You need not be a scholar of dance to be completely enthralled!” - Ernest Hardy, The Village Voice “Illuminating...distills the essence of a time when American dance, like never before, sought to comment on society rather than escape from it.” - Siobhan Burke, The New York Times “Bound to enthrall dance aficionados with its copious amounts of wonderful archival footage. Serves as a marvelous primer on the rise of modern dance as an an important art form in America. Miss Hill herself would no doubt have been pleased.” - Frank Scheck, The Hollywood Reporter “An aesthetic treat, juxtaposing abundant archival footage of such luminaries as Martha Graham, José Límon and Antony Tudor with striking footage of contemporary dancers.” Miss Hill: Making Dance Matter reveals the little known story of Martha Hill, a - lisa Jo sagolla, film Journal international visionary who fought against great odds to make contemporary and modern dance a legitimate art form in America. In a career spanning most of the 20th “Gorgeous and evocative! century, Hill became a behind the scenes leader in the dance world and the The blending of archival footage and voice over founding director of Juilliard’s Dance Division. Stylistically weaving together over 90 years of archival footage, the film is a celebration of dance and an is quite seamless and beautifully done.” examination of the passion required to keep it alive. -Joshua Brunsting, criterion cast DVD BONUS MATERIALS INCLUDE SRP: $27.95 Catalog #: FRF 916561D • ArchivAl DAnce PerformAnce footAge 80 minutes, color, 2014 • AdditionAl interviews • Biographies PRE-BOOK: MAY 26 • STREET DATE: JUNE 23 TO ORDER CALL 1-800-229-8575 OR CONTACT YOUR DISTRIBUTOR Email: [email protected]. -

Alliance for Canadian New Music Projects Presents

Alliance for Canadian New Music Projects presents Festival: November 23 - 25, 2018 Rooms 1-29, 2-28 & Studio 27, University of Alberta, Fine Arts Building Saturday, November 24, 2018 25th Anniversary Commission Classes, 6 - 8 pm Young Composers Program Final Concert, 8 pm Studio 27, University of Alberta, Fine Arts Building Gala Concert: Friday, November 30, 7:00 pm Muttart Hall, Alberta College, 10050 MacDonald Drive 3 4 ALLIANCE FOR CANADIAN Dear Contemporary Showcase Edmonton, NEW MUSIC PROJECTS Congratulations on your 25th Anniversary! This is a major milestone and you are celebrating it in a creative and memorable way. Edmonton has always been a vital Showcase centre, proudly and effectively promoting the teaching, performance and composition of Canadian Music. Throughout the years, we have marvelled at your expansion of musical activities including the establishment of your Young Composers Program and commissioning of works by Albertan composers. Performers from your centre have received many National Awards for their inspired performances which serves as a testament to the lasting impact of your presence. Thanks to the dedicated committee members, through this quarter century, contemporary Canadian music is thriving in Edmonton. We look forward to celebrating many more milestones with you in the years to come! Jill Kelman President ACNMP October 5, 2018 To: Edmonton Contemporary Showcase Congratulations on the 25th Anniversary of Edmonton Contemporary Showcase, a remarkable achievement in presenting this important mechanism for -

Winter-Spring 2006 Newsletter

Salem High School Alumni Association Winter-Spring 2006 Vol. 22, No.1 Martha Hill ’18 Influenced American Dance The Juilliard School’s centennial celebration highlights the enormous influence of dancer and educator Martha Hill, a 1918 Salem High School gradu- ate. Hill was the first director of Juilliard’s Dance Division, which she led for 34 years. “She was so important in so many aspects of dance,” said Janet Soares, who was the head of Barnard College’s dance department until her recent retire- ment. Soares was a student of Hill’s at Juilliard in the 1950s and later served as her assistant. Soares used the personal papers Hill bequeathed her, interviews, and other research for a biography that is currently circulating among publishers. Hill was extremely influential in the merger of modern dance and ballet, and Courtesy of Juilliard School Archives in the development of choreography as Martha Hill was often surrounded by students who became famous. In this group from 1959-60 (left an American art form, according to to right) are Donald McKayle, who choreographed Broadway shows and films; William Louther, who Soares and Elizabeth McPherson, a danced on Broadway and in modern dance companies; Hill; Mabel Robinson, dancer and producer; doctoral student at New York University. for stage and film; Dudley Williams, longtime lead dancer with Alvin Aily American Dance Theater; and “Her idea was to train dancers who Pina Bausch, a ballet choreographer who is now considered “the queen of German dance theater.” could do anything, who could move of American art.” was conceived from what I had discov- from style to style,” McPherson said. -

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy And

Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Tsung-Hsin Lee, M.A. Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee Hannah Kosstrin, Advisor Harmony Bench Danielle Fosler-Lussier Morgan Liu Copyrighted by Tsung-Hsin Lee 2020 2 Abstract This dissertation “Taiwanese Eyes on the Modern: Cold War Dance Diplomacy and American Modern Dances in Taiwan, 1950–1980” examines the transnational history of American modern dance between the United States and Taiwan during the Cold War era. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Carmen De Lavallade-Alvin Ailey, José Limón, Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, and Alwin Nikolais dance companies toured to Taiwan under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. At the same time, Chinese American choreographers Al Chungliang Huang and Yen Lu Wong also visited Taiwan, teaching and presenting American modern dance. These visits served as diplomatic gestures between the members of the so-called Free World led by the U.S. Taiwanese audiences perceived American dance modernity through mixed interpretations under the Cold War rhetoric of freedom that the U.S. sold and disseminated through dance diplomacy. I explore the heterogeneous shaping forces from multiple engaging individuals and institutions that assemble this diplomatic history of dance, resulting in outcomes influencing dance histories of the U.S. and Taiwan for different ends. I argue that Taiwanese audiences interpreted American dance modernity as a means of embodiment to advocate for freedom and social change. -

Dance Theatre of Harlem

François Rousseau François DANCE THEATRE OF HARLEM Founders Arthur Mitchell and Karel Shook Artistic Director Virginia Johnson Executive Director Anna Glass Ballet Master Kellye A. Saunders Interim General Manager Melinda Bloom Dance Artists Lindsey Croop, Yinet Fernandez, Alicia Mae Holloway, Alexandra Hutchinson, Daphne Lee, Crystal Serrano, Ingrid Silva, Amanda Smith, Stephanie Rae Williams, Derek Brockington, Da’Von Doane, Dustin James, Choong Hoon Lee, Christopher Charles McDaniel, Anthony Santos, Dylan Santos, Anthony V. Spaulding II Artistic Director Emeritus Arthur Mitchell PROGRAM There will be two intermissions. Friday, March 1 @ 8 PM Saturday, March 2 @ 2 PM Saturday, March 2 @ 8 PM Zellerbach Theatre The 18/19 dance series is presented by Annenberg Center Live and NextMove Dance. Support for Dance Theatre of Harlem’s 2018/2019 professional Company and National Tour activities made possible in part by: Anonymous; The Arnhold Foundation; Bloomberg Philanthropies; The Dauray Fund; Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; Elephant Rock Foundation; Ford Foundation; Ann & Gordon Getty Foundation; Harkness Foundation for Dance; Howard Gilman Foundation; The Dubose & Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund; The Klein Family Foundation; John L. McHugh Foundation; Margaret T. Morris Foundation; National Endowment for the Arts; New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature; New England Foundation for the Arts, National Dance Project; Tatiana Piankova Foundation; May and Samuel Rudin -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Harlem Intersection – Dancing Around the Double-Bind

HARLEM INTERSECTION – DANCING AROUND THE DOUBLE-BIND A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Judith A. Miller December, 2011 HARLEM INTERSECTION – DANCING AROUND THE DOUBLE-BIND Judith A. Miller Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor School Director Robin Prichard Neil Sapienza _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the College Durand L. Pope Chand Midha, PhD _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School James Slowiak George R. Newkome, PhD _______________________________ Date ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………. 1 II. JOSEPHINE BAKER – C’EST LA VIE …………………..…….…………………..13 III. KATHERINE DUNHAM – CURATING CULTURE ON THE CONCERT STAGE …………………………………………………………..…………30 IV. PEARL PRIMUS – A PERSONAL CRUSADE …………………………...………53 V. CONCLUSION ……………………………………………………………...……….74 BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………………………………………………… 85 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION “Black is Beautiful” became a popular slogan of the 1960s to represent rejection of white values of style and appearance. However, in the earlier decades of the twentieth century black women were daily deflecting slings and arrows thrown at them from all sides. Arising out of this milieu of adversity were Josephine Baker, Katherine Dunham, and Pearl Primus, performing artists whose success depended upon a willingness to innovate, to adapt to changing times, and to recognize and seize opportunities when and where they arose. Baker introduced her performing skills to New York audiences in the 1920s, followed by Dunham in the 1930s, and Primus in the 1940s. Although these decades resulted in an outpouring of cultural and artistic experimentation, for performing artists daring to cross traditional boundaries of gender and race, the obstacles were significant. -

ASSOCIATION for JEWISH STUDIES 37TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE Hilton Washington, Washington, DC December 18–20, 2005

ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES 37TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE Hilton Washington, Washington, DC December 18–20, 2005 Saturday, December 17, 2005, 8:00 PM Farragut WORKS IN PROGRESS GROUP IN MODERN JEWISH STUDIES Co-chairs: Leah Hochman (University of Florida) Adam B. Shear (University of Pittsburgh) Sunday, December 18, 2005 GENERAL BREAKFAST 8:00 AM – 9:30 AM International Ballroom East (Note: By pre-paid reservation only.) REGISTRATION 8:30 AM – 6:00 PM Concourse Foyer AJS ANNUAL BUSINESS MEETING 8:30 AM – 9:30 AM Lincoln East AJS BOARD OF 10:30 AM Cabinet DIRECTORS MEETING BOOK EXHIBIT (List of Exhibitors p. 63) 1:00 PM – 6:30 PM Exhibit Hall Session 1, Sunday, December 18, 2005 9:30 AM – 11:00 AM 1.1 Th oroughbred INSECURITIES AND UNCERTAINTIES IN CONTEMPORARY JEWISH LIFE Chair and Respondent: Leonard Saxe (Brandeis University) Eisav sonei et Ya’akov?: Setting a Historical Context for Catholic- Jewish Relations Forty Years after Nostra Aetate Jerome A. Chanes (Brandeis University) Judeophobia and the New European Extremism: La trahison des clercs 2000–2005 Barry A. Kosmin (Trinity College) Living on the Edge: Understanding Israeli-Jewish Existential Uncertainty Uriel Abulof (Th e Hebrew University of Jerusalem) 1.2 Monroe East JEWISH MUSIC AND DANCE IN THE MODERN ERA: INTERSECTIONS AND DIVERGENCES Chair and Respondent: Hasia R. Diner (New York University) Searching for Sephardic Dance and a Fitting Accompaniment: A Historical and Personal Account Judith Brin Ingber (University of Minnesota) Dancing Jewish Identity in Post–World War II America: -

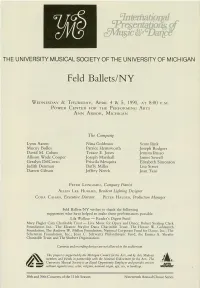

Feld Ballets/NY

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Feld Ballets/NY WEDNESDAY & THURSDAY, APRIL 4 & 5, 1990, AT 8:00 P.M. POWER CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN The Company Lynn Aaron Nina Goldman Scott Rink Mucuy Bolles Patrice Hemsworth Joseph Rodgers David M. Cohen Terace E. Jones Jennita Russo Allison Wade Cooper Joseph Marshall James Sewell Geralyn DelCorso Priscila Mesquita Elizabeth Simonson Judith Denman Buffy Miller Lisa Street Darren Gibson Jeffrey Neeck Joan Tsao PETER LONGIARU, Company Pianist ALLEN LEE HUGHES, Resident Lighting Designer CORA CAHAN, Executive Director PETER HAUSER, Production Manager Feld Ballets/NY wishes to thank the following supporters who have helped to make these performances possible: Lila Wallace Reader's Digest Fund Mary Flagler Gary Charitable Trust Live Music for Opera and Dance; Robert Sterling Clark Foundation Inc.; The Eleanor Naylor Dana Charitable Trust; The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation; The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; National Corporate Fund for Dance, Inc.; The Scherman Foundation, Inc.; Joan C. Schwartz Philanthropic Fund; the Emma A. Sheafer Charitable Trust; and The Shubert Organization. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. This project is supported by the Michigan Council for the Arts, and by Arts Midwest members and friends in partnership with the National Endowment for the Arts. The University Musical Society is an Equal Opportunity Employer and provides services without regard to race, color, religion, national origin, age, sex, or handicap. 38th and 39th Concerts of the lllth Season Nineteenth Annual Choice Series PROGRAM Wednesday, April 4 CONTRA POSE (1990) Choreography: Eliot Feld Music: C. -

Martha Graham Dance Company

2 BROOKLYN ACAOEMY OF MUSIC OCTOBER 1970 BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC I OCTOBER 1970 I 3 Brooklyn Festival of Dance 1970-71 The Brooklyn Academy of Music in cooperation with The Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, Inc. presents the Martha Graham Dance Company By arrangement with H aro ld Shaw Bertram R oss Helen McGehee Mary Hinkson Matt Turney Richard Gain R obert Powell Richard Kuch Patricia Birch Takako A sakawa Phyllis Gutelfus Moss Cohen Diane Gray Judith Hogan Judith Leifer Yuriko Kimura Dawn Suzuki David Hatch Walker Lar Roberson and GUEST ARTLSTS Jane Dudley Jean Erdman Pearl Lang C onducto r : Eugene Lester Associate C onductor: Stanl ey Sussman Settings: l amu Noguchi , Arch Lauterer, Philip Stapp Lighting: Jean Ro entha l and William H. Batchelder Rehearsal Directo r : Patricia Birch C ompany Co-Director: Bertram Ross Production Ma nager : Willia m H. Batchelder Costume Supervision : Ursul a Reed Produced by LeRoy Leatherman The per for m a m:e~ o f the M artha Graham Dance Company at the Brooklyn Academy or Mu~ic are made p os~io l e by g r a nt ~ fro m the ation at Endowment l or the A rt , the Lila Acheson Wallace f-und, The Ford F oundation, the ew York State Council on the A rts and individual donor~ . Baldwin is the official piano o f the B rooklyn Academy o f 1\ t usic. The un a uth o ri .~:e d use of cam er a or recording equipment is ~trict l y prohibited duri ng perform.mce~ . -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 93, 1973-1974, Trip

Segovia, appearing ccc/5 s: Andres in recital this month Oa. < DC LU LL LU < lb Les Hooper, traveler through a crowded ol' world. United dedicates ^riendshq) Sendee. Rooiiqr747aiidDC-10 Friend Sh4>s. Flying New York to the west, why crowd yourself? United people to help you along the way. And extra wide Stretch out. Lean back. And try on a roomy 747 or DC-10 aisles, so you can walk around and get friendly yourself. for size. YouVe also a wide range of stereo entertainment. Another reason more people choose the friendly And a full-length feature film on selected flights skies than any other airline in the land. ($2.00 in Coach). A daily 747 to Los Angeles, and roomy DC-lO's to So call United Air Lines at (212) 867-3000, or your Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Denver and Travel Agent, and put yourself aboard our giant Cleveland. Friend Ships. You can't go west in a bigger way. Only United flies the Friend Ship with so many extras. Extra room to stretch out and relax. Extra friendly The friendly skies ofyour land. Unitedh 747's & DClOb to the West Partners in Travel with Western International Hotels. "FOM THE ELIZABETH ARDEN SALON Our idea. Quick. Simple. Color-coded to be fool-proof. Our System organizesyour skin care by daily skin care soyou can cleanse, skin type, simplified. tone and moisturize more efficiently. And effectively. Introducing ¥or instance, Normal-to-Oily skin The Personal can have its own Clarifying Astringent. Normal-to-Dry skin its own Fragile Skin Care System Skin Toner No matter which skin type have, find a product by Elizabeth Arden.