The Common Thread Between the Beats and the Hungryalists Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isymbols of Water and Woman on Selected Examples of Modern Bengali Literature in the Context of Mythological Tradition.*

© Wagadu Volume 3: Spring 2006 Symbols of Water and Woman iSymbols of Water and Woman on Selected Examples of Modern Bengali Literature in the Context of Mythological Tradition.* Blanka Knotková-Čapková As in many archaic mythological concepts, the four basic elements are represented in the Indian mythology as either male or female: air (wind) and fire are male principles, later personified as male deities – Agni and Vāyu; earth and water (river) are female. The metaphorization of woman as Water and Earthii has a strong essentialist aspect; it points to the symbol of the womb, the mysterious feminine source of life, the “cradle and grave”iii or “womb and tomb”, “the Great Mother symbolizing circularity of life and death” (cf. Kalnická, in Wilkoszewska 2001, 107), who also disposes with the ultimate power over life and death. As such, she personifies the female creative and dynamic cosmic energy, śakti. Together with her male counterpart (personified as male God Śiva), she represents the dual image of cosmical unity and harmony. In heterodox śaktism, she is worshipped as the ultimate spiritual principle, not dependent on the male principle; in śivaismiv, she is described as the left part of Śiva’s body. Śaktism also worships śakti in the metonymical image of yoni, the female genitals, the location of the sensual pleasure and the beginning of life (the way to / from the womb).v Some of the mythological personifications of śakti have been partially patriarchalized and “married” to the male Gods; a possible pre-Indo-European concept of an independent motherly deity (whose image was connected with the vegetation cycle, eternal recreation and rebirth). -

Acquisizioni Fino Al 30 Giugno 2006

AUTORE/CURATORE TITOLO ANNO PRIMA PAROLA DEL TITOLO A A comme …60 fiches de pédagogie concrète 1979 A A voce alta 2002 AA.VV. Dimensioni attuali della professionalità docente 1998 AA.VV. Donne e uomini nelle guerre mondiali 1991 AA.VV. faccia scura della Luna (La) 1997 AA.VV. insegnamento delle scienze nella scuola... (L') 1981 AA.VV. legge antimafia tre anni dopo (La) 1986 AA.VV. Lessico oggi 2003 AA.VV. libro nero del comunismo (Il) 2000 AA.VV. Per conoscere la mafia 1994 AA.VV. Per una nuova cultura dell'azione educativa 1995 AA.VV. Renato Vuillermin… 1981 AA.VV. soggetti dell'autonomia (I) 1999 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 1 1997 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 2 1997 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 3 1997 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 4 1997 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 5 1997 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 6 2000 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 7 2001 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 8 1998 AA.VV. Storia di Torino - vol. 9 1999 AA.VV. Volontariato e mezzogiorno-vol. 1 1986 AA.VV. Volontariato e mezzogiorno-vol. 2 1986 AAI Politica locale dei servizi 1975 Aarts, Flor English Syntactic Structures 1982 Abastado, Claude Messages des médias 1980 Abbate, Michele alternativa meridionale (L') 1968 Abburrà, Luciano modello per l'analisi e la previsione dei flussi…(Un) 2002 Abete, Luigi Professionalità zero? 1979 Abitare Abitare la biblioteca 1984 Abraham, G. sogno del secolo (Il) 2000 Abruzzese, A. Sostiene Berlinguer 1997 Acanfora, L. Come logora insegnare 2002 Accademia di San Marciano guerra della lega di Augusta fino alla battaglia…(La) 1993 Accame, Silvio Perché la storia 1981 Accordo Accordo di revisione del Concordato Lateranense 1984 Accornero, Aris paradossi della disoccupazione (I) 1986 Acerboni, Lidia Italiano-Progetto ARCA 1995 Achenbach, C. -

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Sara Martín Alegre P08/04540/02135 © FUOC • P08/04540/02135 Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Index Introduction............................................................................................... 5 Objectives..................................................................................................... 7 1. Literature 1945-1990: cultural context........................................ 9 1.1. The book market in Britain ........................................................ 9 1.2. The relationship between Literature and the universities .......... 10 1.3. Adaptations of literary works for television and the cinema ...... 11 1.4. The minorities in English Literature: women and post-colonial writers .................................................................... 12 2. The English Novel 1945-1990.......................................................... 14 2.1. Traditionalism: between the past and the present ..................... 15 2.2. Fantasy, realism and experimentalism ........................................ 16 2.3. The post-modern novel .............................................................. 18 3. Drama in England 1945-1990......................................................... 21 3.1. West End theatre and the new English drama ........................... 21 3.2. Absurdist drama and social and political drama ........................ 22 3.3. New theatre companies and the Arts Council ............................ 23 3.4. Theatre from the mid-1960s onwards ....................................... -

American Beat Yogi

Linda T. Klausner Masters Thesis: Literature, Culture, and Media Professor Eva Haettner-Aurelius 22 Apr 2011 American Beat Yogi: An Exploration of the Hindu and Indian Cultural Themes in Allen Ginsberg Klausner ii Table of Contents Preface iii A Note on the Mechanics of Writing v Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Early Life, Poetic Vision, and Critical Perspectives 10 Chapter 2: In India 21 Chapter 3: The Change 53 Chapter 4: After India 79 Conclusion 105 Sources 120 Appendix I. Selected Glossary of Hindi and Sanskrit Words 128 Appendix II. Descriptions of Prominent Hindu Deities 130 Klausner iii Preface I am grateful for the opportunity to have been able to live in Banaras for researching and writing this paper. It has provided me an invaluable look at the living India that Ginsberg writes about, and enabled me to see many facets that would otherwise have been impossible to discover. In the spirit of research and my deep passion for the subject, I braved temperatures nearing 50º Celsius. Not weather particularly conducive to thesis-writing, but what I was able to discover and experience empowers me to do it again in a heartbeat. Since the first draft, I contracted a mosquito-borne tropical illness called Dengue Fever, for which there is no vaccine. I left India for a season to recover, and returned to complete this study. The universe guided me to some amazing mentors, including Anand Prabhu Barat at the literature department of Banaras Hindu University, who specializes in the Eastern spiritual themes of the Beat Generation. She and Ginsberg had corresponded, and he sent her several works including Allen Ginsberg: Collected Works, 1947 – 1980. -

Madhusudan Dutt and the Dilemma of the Early Bengali Theatre Dhrupadi

Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre Dhrupadi Chattopadhyay Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5–34 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk 2016 | The South Asianist 4 (2): 5-34 | pg. 5 Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 5-34 Layered homogeneities: Madhusudan Dutt, and the dilemma of the early Bengali theatre DHRUPADI CHATTOPADHYAY, SNDT University, Mumbai Owing to its colonial tag, Christianity shares an uneasy relationship with literary historiographies of nineteenth-century Bengal: Christianity continues to be treated as a foreign import capable of destabilising the societal matrix. The upper-caste Christian neophytes, often products of the new western education system, took to Christianity to register socio-political dissent. However, given his/her socio-political location, the Christian convert faced a crisis of entitlement: as a convert they faced immediate ostracising from Hindu conservative society, and even as devout western moderns could not partake in the colonizer’s version of selective Christian brotherhood. I argue that Christian convert literature imaginatively uses Hindu mythology as a master-narrative to partake in both these constituencies. This paper turns to the reception aesthetics of an oft forgotten play by Michael Madhusudan Dutt, the father of modern Bengali poetry, to explore the contentious relationship between Christianity and colonial modernity in nineteenth-century Bengal. In particular, Dutt’s deft use of the semantic excess as a result of the overlapping linguistic constituencies of English and Bengali is examined. Further, the paper argues that Dutt consciously situates his text at the crossroads of different receptive constituencies to create what I call ‘layered homogeneities’. -

William Carlos Williams' Indian Son(G)

The News from That Strange, Far Away Land: William Carlos Williams’ Indian Son(g) Graziano Krätli YALE UNIVERSITY 1. In his later years, William Carlos Williams entertained a long epistolary relationship with the Indian poet Srinivas Rayaprol (1925-98), one of a handful who contributed to the modernization of Indian poetry in English in the first few decades after the independence from British rule. The two met only once or twice, but their correspondence, started in the fall of 1949, when Rayaprol was a graduate student at Stanford University, continued long after his return to India, ending only a few years before Williams’ passing. Although Williams had many correspondents in his life, most of them more important and better known literary figures than Rayaprol, the young Indian from the southeastern state of Andhra Pradesh was one of the very few non-Americans and the only one from a postcolonial country with a long and glorious literary tradition of its own. More important, perhaps, their correspondence occurred in a decade – the 1950s – in which a younger generation of Indian poets writing in English was assimilating the lessons of Anglo-American Modernism while increasingly turning their attention away from Britain to America. Rayaprol, doubly advantaged by virtue of “being there” (i.e., in the Bay Area at the beginning of the San Francisco Renaissance) and by his mentoring relationship with Williams, was one of the very first to imbibe the new poetic idiom from its sources, and also one of the most persistent in trying to keep those sources alive and meaningful, to him if not to his fellow poets in India. -

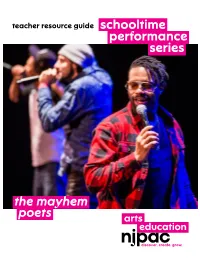

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

One Nation: Power, Hope, Community

one nation power hope community power hope community Ed Miliband has set out his vision of One Nation: a country where everyone has a stake, prosperity is fairly shared, and we make a common life together. A group of Labour MPs, elected in 2010 and after, describe what this politics of national renewal means to them. It begins in the everyday life of work, family and local place. It is about the importance of having a sense of belonging and community, and sharing power and responsibility with people. It means reforming the state and the market in order to rebuild the economy, share power hope community prosperity, and end the living standards crisis. And it means doing politics in a different way: bottom up not top down, organising not managing. A new generation is changing Labour to change the country. Edited by Owen Smith and Rachael Reeves Contributors: Shabana Mahmood Rushanara Ali Catherine McKinnell Kate Green Gloria De Piero Lilian Greenwood Steve Reed Tristram Hunt Rachel Reeves Dan Jarvis Owen Smith Edited by Owen Smith and Rachel Reeves 9 781909 831001 1 ONE NATION power hope community Edited by Owen Smith & Rachel Reeves London 2013 3 First published 2013 Collection © the editors 2013 Individual articles © the author The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1998 to be identified as authors of this work. All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

The Impact of Allen Ginsberg's Howl on American Counterculture

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Vlatka Makovec The Impact of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl on American Counterculture Representatives: Bob Dylan and Patti Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the M.A.in English Language and Literature and Italian language and literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Sintija Čuljat, PhD Co-supervisor: Carlo Martinez, PhD Rijeka, July 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to explore the influence exerted by Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl on the poetics of Bob Dylan and Patti Smith. In particular, it will elaborate how some elements of Howl, be it the form or the theme, can be found in lyrics of Bob Dylan’s and Patti Smith’s songs. Along with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and William Seward Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Ginsberg’s poem is considered as one of the seminal texts of the Beat generation. Their works exemplify the same traits, such as the rejection of the standard narrative values and materialism, explicit descriptions of the human condition, the pursuit of happiness and peace through the use of drugs, sexual liberation and the study of Eastern religions. All the aforementioned works were clearly ahead of their time which got them labeled as inappropriate. Moreover, after their publications, Naked Lunch and Howl had to stand trials because they were deemed obscene. Like most of the works written by the beat writers, with its descriptions Howl was pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression and paved the path to its successors who continued to explore the themes elaborated in Howl. -

Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 12-2013 "Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957 Kayla D. Meyers College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Meyers, Kayla D., ""Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 767. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/767 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull”: Deconstructing The Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies from The College of William and Mary by Kayla Danielle Meyers Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Charles McGovern, Director ________________________________________ Arthur Knight ________________________________________ Marc Raphael Williamsburg, VA December 3, 2013 Table of Contents Introduction: The Poet is Holy.........................................................................................................2 -

Rabindranath's Nationalist Thought

5DELQGUDQDWK¶V1Dtionalist T hought: A Retrospect* Narasingha P. Sil** Abstract : 7DJRUH¶VDQWL-absolutist and anti-statist stand is predicated primarily on his vision of global peace and concord²a world of different peoples and cultures united by amity and humanity. While this grand vision of a brave new world is laudable, it is, nevertheless, constructed on misunderstanding and misreading of history and of the role of the nation state in the West since its rise sometime during the late medieval and early modern times. Tagore views state as an artificial mechanism, indeed a machine thDWWKULYHVRQFRHUFLRQFRQIOLFWDQGWHUURUE\VXEYHUWLQJSHRSOH¶VIUHHGRPDQG culture. This paper seeks to argue that the state also played historically a significant role in enhancing and enriching culture and civilization. His view of an ideal human society is sublime, but by the same token, somewhat ahistorical and anti-modern., K eywords: Anarchism, Babu, Bengal Renaissance, deshaprem [patriotism], bishwajiban [universal life], Gessellschaft, Gemeinschaft, jatiyatabad [nationalism], rastra [state], romantic, samaj [society], swadeshi [indigenous] * $QHDUOLHUVKRUWHUYHUVLRQRIWKLVSDSHUWLWOHG³1DWLRQDOLVP¶V8JO\)DFH7DJRUH¶V7DNH5HYLVLWHG´ZDVSUHVHQWHGWR the Social Science Seminar, Western Oregon University on January 27, 2010 and I thank its convener Professor Eliot Dickinson of the Department of Political Science and Public Administration for inviting me. All citations in Bengali appear in my translation unless stated otherwise. BE stands for Bengali Era that follows the -

The Development of Dylan Thomas' Use of Private Symbolism in Poetry A.Nne" Marie Delap Master of Arts

THE DEVELOPMENT OF DYLAN THOMAS' USE OF PRIVATE SYMBOLISM IN POETRY By A.NNE" MARIE DELAP \\ Bachelor of Arts Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 1964 ~ubmitted to the faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1967 0DAHOMI STATE IJIIVERsifi'li' 1-~BR,AYRV dlNlQN THE DEVELOPMENT OF DYLAN THOMAS O USE OF PRIVATE SYMBOLISM IN POETRY Thesis Approved: n n 11,~d Dean of the Graduate College 658670 f.i PREFACE In spite of numerous explications that have been written about Dylan Thomas' poems, there has been little attention given the growth and change in his symbolism. This study does not pretend to be comprehensive, but will atte~pt, within the areas designated by the titles of chapters 2, 3, and 4, to trace this development. The terms early 129ems and later poems will apply to the poetry finished before and after 1939, which was the year of the publication of The Map tl Love. A number of Thomas• mature poems existed in manu- script form before 1939, but were rewritten and often drastically altered before appearing in their final form. .,After the funera1° ' i is one of these: Thomas conceived the idea for the poem in 1933, but its final form, which appeared in The Map .Q! ~' represents a complete change from the early notebook version. Poem titles which appear in this study have been capitalized according to standard prac- tice, except when derived from the first line of a poem; in thes,e cases only the first word is capitalized.