Affine Maps and Feuerbach's Theorem Arxiv:1711.09391V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yet Another New Proof of Feuerbach's Theorem

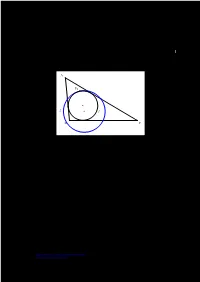

Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: F Mathematics and Decision Sciences Volume 16 Issue 4 Version 1.0 Year 2016 Type : Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4626 & Print ISSN: 0975-5896 Yet Another New Proof of Feuerbach’s Theorem By Dasari Naga Vijay Krishna Abstract- In this article we give a new proof of the celebrated theorem of Feuerbach. Keywords: feuerbach’s theorem, stewart’s theorem, nine point center, nine point circle. GJSFR-F Classification : MSC 2010: 11J83, 11D41 YetAnother NewProofofFeuerbachsTheorem Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of : © 2016. Dasari Naga Vijay Krishna. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Notes Yet Another New Proof of Feuerbach’s Theorem 2016 r ea Y Dasari Naga Vijay Krishna 91 Abstra ct- In this article we give a new proof of the celebrated theorem of Feuerbach. Keywords: feuerbach’s theorem, stewart’s theorem, nine point center, nine point circle. V I. Introduction IV ue ersion I s The Feuerbach’s Theorem states that “The nine-point circle of a triangle is s tangent internally to the in circle and externally to each of the excircles”. I Feuerbach's fame is as a geometer who discovered the nine point circle of a XVI triangle. This is sometimes called the Euler circle but this incorrectly attributes the result. -

Tetrahedra and Relative Directions in Space Using 2 and 3-Space Simplexes for 3-Space Localization

Tetrahedra and Relative Directions in Space Using 2 and 3-Space Simplexes for 3-Space Localization Kevin T. Acres and Jan C. Barca Monash Swarm Robotics Laboratory Faculty of Information Technology Monash University, Victoria, Australia Abstract This research presents a novel method of determining relative bearing and elevation measurements, to a remote signal, that is suitable for implementation on small embedded systems – potentially in a GPS denied environment. This is an important, currently open, problem in a number of areas, particularly in the field of swarm robotics, where rapid updates of positional information are of great importance. We achieve our solution by means of a tetrahedral phased array of receivers at which we measure the phase difference, or time difference of arrival, of the signal. We then perform an elegant and novel, albeit simple, series of direct calculations, on this information, in order to derive the relative bearing and elevation to the signal. This solution opens up a number of applications where rapidly updated and accurate directional awareness in 3-space is of importance and where the available processing power is limited by energy or CPU constraints. 1. Introduction Motivated, in part, by the currently open, and important, problem of GPS free 3D localisation, or pose recognition, in swarm robotics as mentioned in (Cognetti, M. et al., 2012; Spears, W. M. et al. 2007; Navarro-serment, L. E. et al.1999; Pugh, J. et al. 2009), we derive a method that provides relative elevation and bearing information to a remote signal. An efficient solution to this problem opens up a number of significant applications, including such implementations as space based X/Gamma ray source identification, airfield based aircraft location, submerged black box location, formation control in aerial swarm robotics, aircraft based anti-collision aids and spherical sonar systems. -

Theta Circles and Polygons Test #112

Theta Circles and Polygons Test #112 Directions: 1. Fill out the top section of the Round 1 Google Form answer sheet and select Theta- Circles and Polygons as the test. Do not abbreviate your school name. Enter an email address that will accept outside emails (some school email addresses do not). 2. Scoring for this test is 5 times the number correct plus the number omitted. 3. TURN OFF ALL CELL PHONES. 4. No calculators may be used on this test. 5. Any inappropriate behavior or any form of cheating will lead to a ban of the student and/or school from future National Conventions, disqualification of the student and/or school from this Convention, at the discretion of the Mu Alpha Theta Governing Council. 6. If a student believes a test item is defective, select “E) NOTA” and file a dispute explaining why. 7. If an answer choice is incomplete, it is considered incorrect. For example, if an equation has three solutions, an answer choice containing only two of those solutions is incorrect. 8. If a problem has wording like “which of the following could be” or “what is one solution of”, an answer choice providing one of the possibilities is considered to be correct. Do not select “E) NOTA” in that instance. 9. If a problem has multiple equivalent answers, any of those answers will be counted as correct, even if one answer choice is in a simpler format than another. Do not select “E) NOTA” in that instance. 10. Unless a question asks for an approximation or a rounded answer, give the exact answer. -

Barycentric Coordinates in Olympiad Geometry

Barycentric Coordinates in Olympiad Geometry Max Schindler∗ Evan Cheny July 13, 2012 I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail. Abstract In this paper we present a powerful computational approach to large class of olympiad geometry problems{ barycentric coordinates. We then extend this method using some of the techniques from vector computations to greatly extend the scope of this technique. Special thanks to Amir Hossein and the other olympiad moderators for helping to get this article featured: I certainly did not have such ambitious goals in mind when I first wrote this! ∗Mewto55555, Missouri. I can be contacted at igoroogenfl[email protected]. yv Enhance, SFBA. I can be reached at [email protected]. 1 Contents Title Page 1 1 Preliminaries 4 1.1 Advantages of barycentric coordinates . .4 1.2 Notations and Conventions . .5 1.3 How to Use this Article . .5 2 The Basics 6 2.1 The Coordinates . .6 2.2 Lines . .6 2.2.1 The Equation of a Line . .6 2.2.2 Ceva and Menelaus . .7 2.3 Special points in barycentric coordinates . .7 3 Standard Strategies 9 3.1 EFFT: Perpendicular Lines . .9 3.2 Distance Formula . 11 3.3 Circles . 11 3.3.1 Equation of the Circle . 11 4 Trickier Tactics 12 4.1 Areas and Lines . 12 4.2 Non-normalized Coordinates . 13 4.3 O, H, and Strong EFFT . 13 4.4 Conway's Formula . 14 4.5 A Few Final Lemmas . 15 5 Example Problems 16 5.1 USAMO 2001/2 . -

Three Points Related to the Incenter and Excenters of a Triangle

Three points related to the incenter and excenters of a triangle B. Odehnal Abstract In the present paper it is shown that certain normals to the sides of a triangle ∆ passing through the excenters and the incenter are concurrent. The triangle ∆S built by these three points has the incenter of ∆ for its circumcenter. The radius of the circumcircle is twice the radius of the circumcircle of ∆. Some other results concerning ∆S are stated and proved. Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 51M04. Keywords: incenter, PSfragexcenters,replacemenortho center,ts orthoptic triangle, Feuerbach point, Euler line. A B C 1 Introduction a b c Let ∆ := fA; B; Cg be a triangle in the Euclidean plane. The side lengths of α ∆ shall be denoted by c := AB, b := ACβ and a := BC. The interior angles \ \ \ enclosed by the edges of ∆ are β := ABγC, γ := BCA and α := CAB, see Fig. 1. A1 wγ C A2 PSfrag replacements wβ wα C I A B a wα b wγ γ wβ α β A3 A c B Figure 1: Notations used in the paper. It is well-known that the bisectors wα, wβ and wγ of the interior angles of ∆ are concurrent in the incenter I of ∆. The bisectors wβ and wγ of the exterior angles at the vertices A and B and wα are concurrent in the center A1 of the excircle touching ∆ along BC from the outside. 1 S3 nA2 (BC) nI (AB) nA1 (AC) A1 C A2 n (AB) PSfrag replacements I A1 nA2 (AB) B A nI (AC) S2 nI (BC) S1 nA3 (BC) nA3 (AC) A3 Figure 2: Three remarkable points occuring as the intersection of some normals. -

Circles JV Practice 1/26/20 Matthew Shi

Western PA ARML January 26, 2020 Circles JV Practice 1/26/20 Matthew Shi 1 Warm-up Questions 1. A square of area 40 is inscribed in a semicircle as shown: Find the radius of the semicircle. 2. The number of inches in the perimeter of an equilateral triangle equals the number of square inches in the area of its circumscribed circle. What is the radius, in inches, of the circle? 3. Two distinct lines pass through the center of three concentric circles of radii 3, 2, and 1. The 8 area of the shaded region in the diagram is 13 of the area of the unshaded region. What is the radian measure of the acute angle formed by the two lines? (Note: π radians is 180 degrees.) 4. Let C1 and C2 be circles of radius 1 that are in the same plane and tangent to each other. How many circles of radius 3 are in this plane and tangent to both C1 and C2? 1 Western PA ARML January 26, 2020 2 Problems 1. Each of the small circles in the figure has radius one. The innermost circle is tangent to the six circles that surround it, and each of those circles is tangent to the large circle and to its small-circle neighbors. Find the area of the shaded region. 2. A square has sides of length 10, and a circle centered at one of its vertices has radius 10. What is the area of the union of the regions enclosed by the square and the circle? 3. -

The Feuerbach Point and the Fuhrmann Triangle

Forum Geometricorum Volume 16 (2016) 299–311. FORUM GEOM ISSN 1534-1178 The Feuerbach Point and the Fuhrmann Triangle Nguyen Thanh Dung Abstract. We establish a few results on circles through the Feuerbach point of a triangle, and their relations to the Fuhrmann triangle. The Fuhrmann triangle is perspective with the circumcevian triangle of the incenter. We prove that the perspectrix is the tangent to the nine-point circle at the Feuerbach point. 1. Feuerbach point and nine-point circles Given a triangle ABC, we consider its intouch triangle X0Y0Z0, medial trian- gle X1Y1Z1, and orthic triangle X2Y2Z2. The famous Feuerbach theorem states that the incircle (X0Y0Z0) and the nine-point circle (N), which is the common cir- cumcircle of X1Y1Z1 and X2Y2Z2, are tangent internally. The point of tangency is the Feuerbach point Fe. In this paper we adopt the following standard notation for triangle centers: G the centroid, O the circumcenter, H the orthocenter, I the incenter, Na the Nagel point. The nine-point center N is the midpoint of OH. A Y2 Fe Y0 Z1 Y1 Z0 H O Z2 I T Oa B X0 U X2 X1 C Ja Figure 1 Proposition 1. Let ABC be a non-isosceles triangle. (a) The triangles FeX0X1, FeY0Y1, FeZ0Z1 are directly similar to triangles AIO, BIO, CIO respectively. (b) Let Oa, Ob, Oc be the reflections of O in IA, IB, IC respectively. The lines IOa, IOb, IOc are perpendicular to FeX1, FeY1, FeZ1 respectively. Publication Date: July 25, 2016. Communicating Editor: Paul Yiu. 300 T. D. Nguyen Proof. -

Talking Geometry: a Classroom Episode

Learning and Teaching Mathematics, No. 6 Page 3 Talking Geometry: a Classroom Episode Erna Lampen Wits School of Education The Geometry course forms part of the first year early in the course and they used the programme mathematics offering for education students at to investigate their conjectures in an informal way Wits School of Education. The course is outside class time. The course has a distinctly compulsory for all first years who want to major problem-centred approach. Students did not get in mathematics education at FET level. Most of demonstrations of the constructions or guidelines these students obtained about 60% on standard that show “How to construct a line perpendicular grade for mathematics at Grade 12 level and to another line.” Instead, we discussed what it many confessed not to have done geometry means to ask “spatial” questions, and decided beyond Grade 9 level. A few students who together that spatial questions involve questions specialize in Foundation Phase as well as about shape, structure, size and position. The Intermediate and Senior Phase also attended. This course is dedicated to asking and seeking answers class consisted of 85 students of whom close to to spatial questions. We started by investigating 70 attended regularly. All eleven official languages relative positions of points and lines in a plane. were represented in the class. There was also a We did constructions to answer questions like: deaf student and a Chinese student who “Where are all points that are equidistant from a immigrated in 2005 – imagine the need to have given point A? Where are all points that are shared objects to refer to when we discussed the equidistant from two given points A and B?” and mathematics! There was always a tutor, a fellow so on. -

Geometry of the Triangle

Geometry of the Triangle Paul Yiu 2016 Department of Mathematics Florida Atlantic University A b c B a C August 18, 2016 Contents 1 Some basic notions and fundamental theorems 101 1.1 Menelaus and Ceva theorems ........................101 1.2 Harmonic conjugates . ........................103 1.3 Directed angles ...............................103 1.4 The power of a point with respect to a circle ................106 1.4.1 Inversion formulas . ........................107 1.5 The 6 concyclic points theorem . ....................108 2 Barycentric coordinates 113 2.1 Barycentric coordinates on a line . ....................113 2.1.1 Absolute barycentric coordinates with reference to a segment . 113 2.1.2 The circle of Apollonius . ....................114 2.1.3 The centers of similitude of two circles . ............115 2.2 Absolute barycentric coordinates . ....................120 2.2.1 Homotheties . ........................122 2.2.2 Superior and inferior . ........................122 2.3 Homogeneous barycentric coordinates . ................122 2.3.1 Euler line and the nine-point circle . ................124 2.4 Barycentric coordinates as areal coordinates ................126 2.4.1 The circumcenter O ..........................126 2.4.2 The incenter and excenters . ....................127 2.5 The area formula ...............................128 2.5.1 Conway’s notation . ........................129 2.5.2 Conway’s formula . ........................130 2.6 Triangles bounded by lines parallel to the sidelines . ............131 2.6.1 The symmedian point . ........................132 2.6.2 The first Lemoine circle . ....................133 3 Straight lines 135 3.1 The two-point form . ........................135 3.1.1 Cevian and anticevian triangles of a point . ............136 3.2 Infinite points and parallel lines . ....................138 3.2.1 The infinite point of a line . -

Feuerbach's Theorem, and a Brief Biographical Note on Karl Feuerbach

FEURBACH's THEOREM A NEW PURELY SYNTHETIC PROOF Jean - Louis AYME 1 A Fe 2 1 B C Abstract. We present a new purely synthetic proof of the Feuerbach's theorem, and a brief biographical note on Karl Feuerbach. The figures are all in general position and all cited theorems can all be demonstrated synthetically. Summary A. A short biography of Karl Feuerbach 2 B. Four lemmas 3 1. Lemma 1 Example 1 Example 2 2. Lemma 2 3. Lemma 3 4. Lemma 4 C. Proof of Feuerbach’s theorem 7 Remerciements. Je remercie très vivement le Professeur Francisco Bellot Rosado d'avoir relu et traduit en espagnol cet article qu’il a publié dans sa revue électronique Revistaoim 2 ainsi que le professeur Dmitry Shvetsov pour l’avoir traduit en russe et publié dans son site Geometry.ru 3. 1 St-Denis, Île de la Réunion (France), le 25/11/2010. 2 El teorema de Feuerbach : una demonstration puramente sintética, Revistaoim 26 (2006) ; http://www.oei.es/oim/revistaoim/index.html 3 http://geometry.ru/articles.htm 2 A. A SHORT BIOGRAPHY OF KARL FEUERBACH 4 Karl Feuerbach, the brother of the famous philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach, was born on the 30th of May 1800 in Jena (Germany). Son of the jurist Paul Feuerbach and of Eva Troster, he was a brilliant student at the Universities of Erlangen and Freiburg, and received his doctorate at the age of 22 years. He started teaching mathematics at the Gymnasium of Erlangen in 1822 but he continued to frequent a circle of his ancient fellow' students known for their debauchery and debts. -

MYSTERIES of the EQUILATERAL TRIANGLE, First Published 2010

MYSTERIES OF THE EQUILATERAL TRIANGLE Brian J. McCartin Applied Mathematics Kettering University HIKARI LT D HIKARI LTD Hikari Ltd is a publisher of international scientific journals and books. www.m-hikari.com Brian J. McCartin, MYSTERIES OF THE EQUILATERAL TRIANGLE, First published 2010. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the publisher Hikari Ltd. ISBN 978-954-91999-5-6 Copyright c 2010 by Brian J. McCartin Typeset using LATEX. Mathematics Subject Classification: 00A08, 00A09, 00A69, 01A05, 01A70, 51M04, 97U40 Keywords: equilateral triangle, history of mathematics, mathematical bi- ography, recreational mathematics, mathematics competitions, applied math- ematics Published by Hikari Ltd Dedicated to our beloved Beta Katzenteufel for completing our equilateral triangle. Euclid and the Equilateral Triangle (Elements: Book I, Proposition 1) Preface v PREFACE Welcome to Mysteries of the Equilateral Triangle (MOTET), my collection of equilateral triangular arcana. While at first sight this might seem an id- iosyncratic choice of subject matter for such a detailed and elaborate study, a moment’s reflection reveals the worthiness of its selection. Human beings, “being as they be”, tend to take for granted some of their greatest discoveries (witness the wheel, fire, language, music,...). In Mathe- matics, the once flourishing topic of Triangle Geometry has turned fallow and fallen out of vogue (although Phil Davis offers us hope that it may be resusci- tated by The Computer [70]). A regrettable casualty of this general decline in prominence has been the Equilateral Triangle. Yet, the facts remain that Mathematics resides at the very core of human civilization, Geometry lies at the structural heart of Mathematics and the Equilateral Triangle provides one of the marble pillars of Geometry. -

Mod 5 10H Aim 3.Pdf

CC Geometry H Aim #3: What is the relationship between tangents to a circle from an outside point? Do Now: Find the value of each variable. q0 0 0 1. 2. 0 0 95 3. 4. p a c 250 0 x0 72 b0 b0 580 0 c0 y a0 THEOREM: ____________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________ B A Given: Circle O, center O O Prove: Theorem, AB ≅ AC C 1. Circle O, center O 1. Given 2. Draw OB, OC, OA. 2. Two points determine a segment. 1. PS and PT are tangent segments. a) Solve for x, if SP = x2 - 5x, TP = 3x2 + 4x - 5. b) Find SP. S P T Definition: A circle circumscribed about a polygon is a circle that passes through each vertex of the polygon. Definition: A circle inscribed in a polygon is a circle that has a point of tangency with each side of the polygon. CIRCUMSCRIBED CIRCLE INSCRIBED CIRCLE (inscribed polygon) (circumscribed polygon) Each side of the inscribed polygon is a Each side of the circumscribed polygon _________________ of the circle. is a _________________ to the circle. 2. Circle O is inscribed in ΔABC. Find the perimeter of ΔABC. B E 8 F A O 10 D 15 C 3. ΔCDE is circumscribed about circle O. Find DE. F G O C #4-6 Each polygon circumscribes the circle. Find the perimeter of the polygon. 4. 9 cm 5. 13 in. O 10 in. O 14 in. 13 cm 16 cm 8 in. 5 m 6. 11 m 7.5 m O 5 m 7 m 7.