Bloom-Craft-Paper.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing Program 1

Writing Program 1 Elizabeth (Beth) Ann Hepford BA, University Of Kansas; MA, Arizona State University; PHD, Temple University WRITING PROGRAM Assistant Professor of the Practice in TESOL; Assistant Professor of the Practice, Wesleyan offers students a vibrant writing community and a multitude of ways Education Studies; Assistant Professor of the Practice, English to pursue their interest in writing. Writers, editors, and publishers visit campus throughout the year, and students support more than 20 magazines, journals, Douglas Arthur Martin and literary groups. The curriculum emphasizes academic writing in many subject BA, University of Georgia Athens; MFA, The New School; PHD, CUNY The areas and also offers courses in fiction writing, creative nonfiction, poetry, Graduate Center screenwriting, playwriting, and mixed forms. The establishment of the Shapiro Assistant Professor of the Practice in Creative Writing; Assistant Director, Creative Writing Center at 167 High Street signals the importance the University Creative Writing; Assistant Professor of the Practice, English attaches to writing. The Shapiro Center serves as a hub for writing activities Sarah Ryan and provides a venue for readings, workshops, colloquia, informal discussions, BA, Capital University; JD, Quinnipiac University; MLS, Texas Womans University; student-generated events, and receptions. Its lounge is open to all students PHD, Ohio University enrolled in creative-writing courses. The Shapiro Center also houses writing Associate Professor of the Practice in Oral Communication faculty, including fiction writer Amy Bloom, the Distinguished University Writer- in-Residence. Lauren Silber BA, University of Connecticut; MA, University of Massachusetts Amherst; PHD, The creative writing concentration in the English major. This concentration University of Massachusetts Amherst allows students to pursue creative writing at a high level in the context of Assistant Professor of the Practice in Academic Writing; Assistant Professor of advanced literary study. -

2020 Brochure

2020 Summer Workshops... • Poetry Workshop: June 20 - 27, 2020 • Writers Workshops in Fiction, Nonfiction & Memoir: July 6-13, 2020 The Community of Writers For 50 summers, the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley has brought together poets and prose writers for separate weeks of workshops, individual conferences, lectures, panels, readings, and discussions of the craft and the business of writing. Our aim is to assist writers to improve their craft and thus, in an atmosphere of camaraderie and mutual support, move them closer to achieving their goals. The Community of Writers holds its summer writing workshops in Squaw Valley at the foot of the ski slopes. Panels, talks, staff readings and workshops take place in a ski lodge with a spectacular view up the mountain. ...& Other Projects • Published Alumni Reading Series: Recently published Writers Workshops alumni are invited to return to the valley to read from their books and talk about their journeys from unpublished writers to published authors. • Omnium Gatherum & Alumni News Blog: Chronicling the publications and other successes of its participants. • Craft Talk Anthology – Writers Workshop in a Book: An anthology of craft talks from the workshops, edited by Alan Cheuse and Lisa Alvarez. • Annual Benefit Poetry Reading: An annual event to raise funds for the Poetry Workshop’s Scholarship Fund. • Notable Alumni Webpage: A website devoted to a list of our notable alumni. • The OGQ: Omnium Gatherum Quarterly : The OGQ is an invitational online quarterly magazine of prose and poetry, founded in 2019 as part of the 50th Anniversary of the Commu- nity of Writers. OGQ seeks to feature works first written in, discovered during, or inspired by the week in the valley. -

Community Ofwriters Summer Writing Workshops

COMMUNITY SUMMER WRITING WORKSHOPS OFWRITERS POETRY WORKSHOP: June 22-29, 20i3 WRITERS WORKSHOPS: July 8-i5, 20i3 SCREENWRITING WORKSHOP: July 8-i5, 20i3 COMMUNITY OF WRITERS AT SQUAW VALLEY FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE For 43 summers, the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley A limited amount of financial aid is available from funds donated has brought together poets, prose writers, and screenwriters for by generous individuals and institutions. Requests for financial separate weeks of workshops, individual conferences, lectures, aid should accompany applications. Assistance is provided in the panels, readings, and discussions of the craft and the business form of partial tuition waivers and scholarships. of writing. Our aim is to assist writers to improve their craft and thus move them closer to achieving their goals. TRAVEL Squaw Valley is located seven miles from Tahoe City and ten SQUAW VALLEY, CALIFORNIA miles from Truckee. It is a four-hour drive from the Bay Area, Squaw Valley, a ski resort located in the California Sierra and an hour from the Reno/Lake Tahoe International Airport. Nevada close to the north shore of Lake Tahoe, was the site It is not necessary to have a car during the week. Upon accep- of the 1960 Winter Olympics. Summers are warm and sunny; tance, participants will be sent more information about air- participants will have opportunities to hike to the local water- port shuttles, ride-sharing to the valley, and accommodations. falls, take nature walks up the mountain, swim in Lake Tahoe, and play tennis, ice skate, and bike along the Truckee River. HOUSING & MEALS Evening meals are included in the tuition, but participants are THE WORKSHOPS on their own for breakfast and lunch. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Kwame Anthony Akroma-Ampim Kusi APPIAH Professor of Philosophy and Law, New York University Laurance S. Rockefeller University Professor of Philosophy and the University Center for Human Values Emeritus, Princeton University Honorary Fellow, Clare College, Cambridge NYU Dept. of Philosophy NYU School of Law Rm. 508, 5 Washington Place Rm. 337, Vanderbilt Hall New York, New York 10003 40 Washington Square South New York, NY 10012 (212) 998 8227 (212) 992 9787 Department Assistant, Veronica Cruz (212) 998 8320 (212) 998 6653 fax: (212) 995 4179 [email protected] WEBSITE: http://www.appiah.net E-MAIL: [email protected] EFAX: (413) 208 0985 LITERARY AGENT: Lynn Nesbit Janklow & Nesbit Associates 445 Park Avenue New York, NY 10022 (212) 421 1700 Fax: (212) 980 3671 http://www.janklowandnesbit.com/ LECTURE AGENT: David Lavin The Lavin Agency 222 Third Street, Suite 1130 Cambridge, MA 02142 (800) 762 4234 Fax: (617) 225 7875 http://www.thelavinagency.com/ CITIZENSHIP: United States DATE OF BIRTH: 8 May 1954 LANGUAGES: Asante-Twi, English, French, German, Latin Kwame Anthony Appiah ~ Curriculum Vitae 2 EDUCATION Clare College, Cambridge University, 1972-75 Exhibition, Medical Sciences 1972 First Class Honours (Part I b) 1974 Exhibition, Philosophy 1974 First Class Honours (Part II) 1975 BA (Honours), Philosophy 1975, MA 1980 1976-81 PhD, Philosophy 1982 (Thesis: Conditions for Conditionals) EMPLOYMENT New York University Professor of Philosophy and Law January 2014- Princeton Laurance S. Rockefeller University Professor of Philosophy and the University Center for Human Values July 2002-2014 Associated Fields: African-American Studies (2002—2014), African Studies (2002—2014) Comparative Literature (2005—2014), Politics (2006— 2014), Program in Translation and Intercultural Communication (2007— 2014), Program in Gender and Sexuality Studies (2012—2014) Bacon-Kilkenny Visiting Professor, Fordham University School of Law Fall 2008 Phi Beta Kappa-Romanell Professor, 2008-2009 Professor Emeritus, 2014- Harvard Charles H. -

CAS Connections Performing in Ontario, Canada, Western New York, and Western Pennsylvania

VOL. 17,#, NNOO.. #,3, MDATEAY, 2005 YEAR MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN In This Issue... It has been quite a year in CAS; and with the Katzen Center opening in the fall, next year promises to be equally exciting and successful. Before we turn our focus to the • hereValerie is where French we put bulletedand Gail blurbs of top future, I’d like to list just a few of the many accomplishments of CAS faculty, Humphriesstories and pg #s Mardirosian where story is co-teach students, and programs in this academic year. an interdisciplinary honors course investigating ancient Greece. Story · CAS development efforts brought $1.1 million in cash gifts from alumni, on page 3. friends, faculty, and staff to support scholarships, faculty and student research and creative work, and curriculum development across the college. th · The 15 annual CAS Student Research Conference, renamed this year for • CAS alumna Alison Pace talks Ann Robyn Mathias, AU alumna and CAS benefactor, featured the research about her first novel, art, and love. and creative work of more than 200 undergraduate and graduate students. Story on page 10. · CAS faculty members who were honored with university awards for excellence included Richard McCann, literature (Scholar-Teacher of the Year), Robert Blecker, economics (Outstanding Teaching), Cathy Schaeff, • Deborah Kahn discusses her biology (Outstanding Faculty Administrator), Nancy Jo Snider, music/ painting and the lonely quest to performing arts (Outstanding Teaching by an Adjunct), and Lucinda Joy create meaniful art. Page 12. Peach, philosophy and religion (Morton Bender Prize for scholarly achievements by an associate professor). • The 15th Annual Ann Robyn Mathias Student Research Conference showcases student continued on page 2 work. -

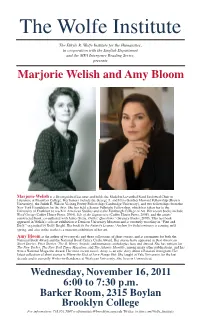

The Wolfe Institute the Ethyle R

The Wolfe Institute The Ethyle R. Wolfe Institute for the Humanities, in cooperation with the English Department and the MFA Intergenre Reading Series, presents Marjorie Welish and Amy Bloom Marjorie Welish is a Distinguished Lecturer and holds the Madelon Leventhal Rand Endowed Chair in Literature at Brooklyn College. Her honors include the George A. and Eliza Gardner Howard Fellowship (Brown University), the Judith E. Wilson Visiting Poetry Fellowship (Cambridge University), and two fellowships from the New York Foundation for the Arts. She has held a Senior Fulbright Fellowship, which has taken her to the University of Frankfurt to teach in American Studies and to the Edinburgh College of Art. Her recent books include Word Group (Coffee House Press, 2004), Isle of the Signatories (Coffee House Press, 2008), and the artists’ constructed book, co-authored with James Siena, Oaths? Questions? (Granary Books, 2009). This last book appeared in Welish’s solo art exhibition at Denison University Museum and is currently traveling in “Fine and Dirty,” organized by Betty Bright. Her book In the Futurity Lounge / Asylum for Indeterminacy is coming next spring, and also in the works is a museum exhibition of her art. Amy Bloom is the author of two novels and three collections of short stories, and is a nominee for both the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her stories have appeared in Best American Short Stories, Prize Stories: The O. Henry Awards, and numerous anthologies here and abroad. She has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, and The Atlantic Monthly, among many other publications, and has won a National Magazine Award.