Prison Metaphors in Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Shawshank Trail Drive-It-Yourself Tour the Shawshank Trail Drive-It

hope mobile.ShawshankTrail.com ShawshankTrail.com Hollywood Comes To Mansfield, Ohio Mansfield, To Comes Hollywood fear ShawshankTrail.com your journey journey your 800-642-8282 • MansfieldTourism.com • 800-642-8282 Open to start start to Open 124 North Main Street • Mansfield, Ohio 44902 44902 Ohio Mansfield, • Street Main North 124 of Mexico. Mexico. of meet Andy on the coast coast the on Andy meet Hollywood once did. did. once Hollywood eventually leads him to to him leads eventually same sites as as sites same beneath a tree, which which tree, a beneath you free. you area visiting the the visiting area find a further note hidden hidden note further a find rock collecting. rock and the surrounding surrounding the and can set set can given to him by Andy to to Andy by him to given own in order to pursue a hobby in in hobby a pursue to order in own around Mansfield Mansfield around he follows the instructions instructions the follows he Dufresne, an object he wishes to hope to wishes he object an Dufresne, Navigate your way way your Navigate finally released from prison, prison, from released finally things”, obtains a rock hammer for for hammer rock a obtains things”, his arrival. When Red is is Red When arrival. his “the man who knows how to get get to how knows who man “the Park. Park. given to him shortly after after shortly him to given Redding (Morgan Freeman). Red, Red, Freeman). (Morgan Redding Malabar Farm State State Farm Malabar you prisoner. you walls with the rock hammer hammer rock the with walls befriends fellow prisoner Ellis “Red” “Red” Ellis prisoner fellow befriends Reformatory and and Reformatory fear hold can by tunneling through the the through tunneling by maximum security penitentiary. -

The Route Towards the Shawshank Redemption: Mapping Set-Jetting with Social Media and Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

The Route Towards The Shawshank Redemption: Mapping Set-jetting with Social Media Mengqian Yang A Thesis in The Department of Geography, Planning & Environment Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Geography, Urban and Environmental Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2015 © Mengqian Yang, 2015 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Mengqian Yang Entitled: The Route Towards The Shawshank Redemption: Mapping Set-jetting with Social Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Geography, Urban and Environmental Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: Dr. Pascale Biron Chair Dr. Thierry Joliveau Examiner Dr. Christian Poirier Examiner Dr. Sébastien Caquard Supervisor Approved by Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director Dean of Faculty 2015 Date ABSTRACT The Route Towards The Shawshank Redemption: Mapping Set-jetting with Social Media Mengqian Yang With the development of the Web 2.0, more and more geospatial data are generated via social media. This segment of what is now called “big data” can be used to further study human spatial behaviors and practices. This project aims to explore different ways of extracting geodata from social media in order to contribute to the growing body of literature dedicated to studying the contribution of the geoweb to human geography. More specifically, this project focuses on the potential of social media to explore a growing tourism phenomenon: set-jetting. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} the Three Kings Ebook Free Download

THE THREE KINGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Leo Moynihan | 272 pages | 20 Aug 2020 | Quercus Publishing | 9781787475694 | English | London, United Kingdom The Three Kings PDF Book Her words were so filled with divine truth that the Wise Men were deeply moved and wished that they did not have to depart from her. After his brother's death, he joined his father as co-pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church. We have so much in common and we really love spending time together. She died in Comments are closed. Leave a Reply Cancel reply Your email address will not be published. And after having assembled their gifts and put on their great, white silk cloaks, they set out for the grotto in an orderly procession with their relatives and servants. The race is followed by festivities. Epiphany is celebrated around the world and there are a wide array of customs specific to the region. Circa Parades and performances are also typical on Three Kings' day. In , chefs from La Universidad Vizcaya de las Americas were awarded the Guinness record for the longest Rosca de Reyes bread in the world. Children of the Corn - Can you imagine being trapped in a small town full of murderous children? The children leave their shoes by the door along with grass and water for the camels, the night before. In their world adults are not allowed Joseph suggested that they move to a more comfortable dwelling in Bethlehem. When's the First Day of Fall in ? Carrie - This is the movie that defined Stephen King and made viewers everywhere demand more adaptations. -

Chapter Iii Analysis

I s n a i n i | 21 CHAPTER III ANALYSIS The focus of this chapter is to answer all the statement of the problem in chapter one. This chapter is divided into two parts. First, this research analyzes the character of Andy Dufresne. Second, this research analyzes types and also the way how Andy Dufresne has undergone his defense mechanism by Sigmund Freud in Stephen King‟s Rita Hayworth and The Shawshank Redemption novel. The types of defense mechanism that are used by the major character Andy Dufresne, there are six types that the researcher found in Rita Hayworth and The Shawshank Redemption novel. Each type will be analyzed by using Sigmund Freud‟s defense mechanism theories. It is includes the types, and how the main character perform the defense mechanism itself. 3.1 Character of Andy Dufresne Characters in work of fiction are generally designed to open up or explore certain aspects of human experience. Characters often depict particular traits of human nature; they may represent only one or two traits – a greedy old man who has forgotten how to care about others, for instance, or they may represent very complex conflicts, values and emotions. Likewise, Knickerbocker and Reninger explain that the nature and use of characters in any story are determined by the purpose of the author (18). digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id digilib.uinsby.ac.id I s n a i n i | 22 In similar views, a narrator may be external, outside the story, telling it with an ostensibly objective and omniscient voice; or a narrator may be a character (or characters) within the story, telling the story in the first person (either central characters or observer characters, bit players looking in on the scene). -

The Shawshank Trail Drive-It-Yourself Tour the Shawshank Trail Drive-It

ShawshankTrail.com ShawshankTrail.com Hollywood Comes To Mansfield, Ohio Mansfield, To Comes Hollywood 6/12 ShawshankTrail.com 800-642-8282 • MansfieldTourism.com • 800-642-8282 your journey journey your 124 North Main Street • Mansfield, Ohio 44902 44902 Ohio Mansfield, • Street Main North 124 Open to start start to Open of Mexico. Mexico. of meet Andy on the coast coast the on Andy meet Hollywood once did. did. once Hollywood eventually leads him to to him leads eventually same sites as as sites same /PU beneath a tree, which which tree, a beneath you free. you area visiting the the visiting area find a further note hidden hidden note further a find rock collecting. rock can set set can and the surrounding surrounding the and given to him by Andy to to Andy by him to given own in order to pursue a hobby in in hobby a pursue to order in own around Mansfield Mansfield around he follows the instructions instructions the follows he Dufresne, an object he wishes to to wishes he object an Dufresne, Navigate your way way your Navigate finally released from prison, prison, from released finally things”, obtains a rock hammer for for hammer rock a obtains things”, his arrival. When Red is is Red When arrival. his “the man who knows how to get get to how knows who man “the Park. Park. given to him shortly after after shortly him to given Redding (Morgan Freeman). Red, Red, Freeman). (Morgan Redding Malabar Farm State State Farm Malabar walls with the rock hammer hammer rock the with walls you prisoner. -

Shawshank Redemption

THE SHAWSHANK REDEMPTION by Frank Darabont Based upon the story Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption by Stephen King 1 INT -- CABIN -- NIGHT (1946) A dark, empty room. The door bursts open. A MAN and WOMAN enter, drunk and giggling, horny as hell. No sooner is the door shut than they're all over each other, ripping at clothes, pawing at flesh, mouths locked together. He gropes for a lamp, tries to turn it on, knocks it over instead. Hell with it. He's got more urgent things to do, like getting her blouse open and his hands on her breasts. She arches, moaning, fumbling with his fly. He slams her against the wall, ripping her skirt. We hear fabric tear. He enters her right then and there, roughly, up against the wall. She cries out, hitting her head against the wall but not caring, grinding against him, clawing his back, shivering with the sensations running through her. He carries her across the room with her legs wrapped around him. They fall onto the bed. CAMERA PULLS BACK, exiting through the window, traveling smoothly outside... 2 EXT -- CABIN -- NIGHT (1946) 2 ...to reveal the bungalow, remote in a wooded area, the lovers' cries spilling into the night... ...and we drift down a wooded path, the sounds of rutting passion growing fainter, mingling now with the night sounds of crickets and hoot owls... ...and we begin to hear FAINT MUSIC in the woods, tinny and incongruous, and still we keep PULLING BACK until... ...a car is revealed. A 1946 Plymouth. Parked in a clearing. -

The Reel Prison Experience

SMU Law Review Volume 55 Issue 4 Article 7 2002 "Failure to Communicate" - The Reel Prison Experience Melvin Gutterman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Melvin Gutterman, "Failure to Communicate" - The Reel Prison Experience, 55 SMU L. REV. 1515 (2002) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol55/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. "FAILURE To COMMUNICATE ' t THE REEL PRISON EXPERIENCE Melvin Gutterman* I. INTRODUCTION HE academic legal community has failed to appropriately recog- nize the images of law depicted by Hollywood as a legitimate and important subject for scholarly review.' Movies have the capacity to "open up" the discussion of contemporary legal issues that conven- tional legal sources ignore. 2 Although different from the normative legal theory of study, movies provide a rich portrait of popular jurisprudence of legal values.3 A fundamental paradox of many notable films is their inability to simultaneously achieve both scholastic acceptance and artistic achievement, at least equal to other media. 4 Movies are very powerful and can, through the use of provocative images, explore controversial themes and evoke passions that can affect even the most tightly closed minds. 5 The exclusion of films' celebrated images from academic study has its cost. There is, for example, a prevalent belief that life in prison is too t In the most celebrated colloquy in the movie Cool Hand Luke, the Captain as he stands over the defiant convict Luke asserts, "[w]hat we've got here is failure to communicate." What the Captain actually demands is that Luke totally capitulate to the contemptible prison system he embodies. -

The Shawshank Redemption”

English Language Teaching; Vol. 13, No. 5; 2020 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education An Interpretation of Influences of Institutionalization on the Fate of Characters in “The Shawshank Redemption” Yuan-yuan Peng1 1 Tourism Department of Leshan Vocational & Technical College, China Correspondence: Yuan-yuan Peng, Tourism Department of Leshan Vocational & Technical College, Leshan, Sichuan, China. Received: March 2, 2020 Accepted: March 31, 2020 Online Published: April 9, 2020 doi: 10.5539/elt.v13n5p11 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v13n5p11 Abstract Institutionalization is mentioned over and over again in film “The Shawshank Redemption”. In this film, the institution refers to the fixed prison institution, and institutionalization refers to a process of rigidifying prisoners’ behaviors, thoughts and mindsets in some imperceptible constraint mechanisms. In this process, the prisoners are forced to change their original behaviors, thoughts and ideas, and begin to accept, get used to and even depend on the current situation little by little. As a result, they become obedient to such prison management. They don’t want or dare to change their realistic conditions, but have to depend on them for survival. The death of Brooks, pigeon Jake and Tommy, the fear of Red and the escape of Andy are all associated with institutionalization. In this paper, influences of institutionalization on the fate of characters in “The Shawshank Redemption” were analyzed. In addition, the wisdom of coping with and avoiding institutionalization was preliminarily analyzed. Keywords: institutionalization, anti-institutionalization, survival strategies 1. Connotations of institutionalization 1.1 What Is Institutionalization? To define institutionalization, Red has vividly described his personal experience of decades-long prison life in the film: "These walls are funny. -

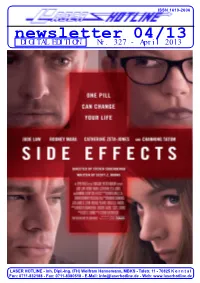

Newsletter 04/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 04/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 327 - April 2013 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 04/13 (Nr. 327) April 2013 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, einer großzügigen DVD-Spende für die Geheimtipp gekürt hat. Der Clou dabei: im liebe Filmfreunde! Inhaber einer Dauerkarte haben wir auch Anschluss an die Filmvorführung geben die noch den offiziellen Festival-Trailer vom Darsteller aus dem Film ein 60-minütiges “Gut Ding braucht Weile” heisst es ja so Videoformat in ein professionelles DCP Bluegrass-Konzert auf der Bühne des Ki- schön in einem alten deutschen Sprichwort. umgewandelt – inklusive eines sauberen nosaals. Gänsehaut ist garantiert! Und Und genau so verhält es sich auch mit un- 5.1-Upmixes des vorhandenen Stereo- ganz wichtig: ausreichend Taschentücher serem Newsletter. Denn auch der braucht Sounds! Wer sich für das “Widescreen mitbringen – der Film hat es in sich! eine ganze Weile, um den Zustand zu errei- Weekend” interessiert, dem sei die offiziel- chen, in dem wir ihn bedenkenlos versen- le Website des Festivals nahegelegt: http:// Und jetzt wünschen wir viel Spaß beim den können. Was genau jetzt passiert ist, www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk/ Lesen! wie Sie sicherlich bemerkt haben, seit Sie BradfordInternationalFilmFestival.aspx. das “gut Ding” in Händen halten oder on- Aufgrund unserer Teilnahme am Festival Ihr Laser Hotline Team line lesen. Lange Rede, kurzer Sinn: der wird unser Büro in der Zeit vom Newsletter ist einmal mehr ziemlich ver- 24.04.2013 bis einschließlich 01.05.2013 spätet, weist dafür aber fast doppelt so geschlossen bleiben. -

Ka Hue Anahā Journal of Academic & Research Writing Spring 2015

Ka Hue Anahā Journal of Academic & Research Writing Spring 2015 Kapi‘olani Community College Board of Student Publications Ka Hue Anahā Journal of Academic & Research Writing Board of Student Publications 4303 Diamond Head Road Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96816 Spring 2015 Ka Hue Anahā / Spring 2015 Ka Hue Anahā publishes academic and research writing in all disciplines and programs and from all courses, except for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math research reports, which are published in a separate journal. The name, given by LLL Department Chair and Hawaiian language professor Nawa’a Napoleon, translates as “The calabash of light” or “The wellspring of reflected light,” and is meant to reflect the diversity of opinions and spectrum of cultures our island state fosters, and also pays homage to the concept of ‘welcoming ideas from across the curriculum’ previously engendered in a 2004-2006 publication called Spectrum. Ka hue – gourd, water calabash, any narrow-necked vessel for holding water. A way of connecting net sections by, interlocking meshes. Anahā – reflection of light Faculty Coordinator/Copy-Editor: Davin Kubota ([email protected]) Selection Committee: D. Uedoi, D. Oshiro, D. Kubota, M. Sakurai, M. Archer Note to Students: Since submissions are always accepted on a rolling basis, feel free to submit your academic and research papers in .doc or .txt format together with your course name/instruc- tor, with a clearly-rendered subject line (e.g. JOUR 201: Submission!) to [email protected]. The coordinators and committee will then contact you should your work be selected for the next edition. We sincerely look forward to having your work included in the next Ka Hue Anahā! Note to Faculty: Please offer extra-credit incentives or build in publication incentives as part of the writing process. -

Serassis / Kania / Albrecht (Eds.) Images of Crime

Serassis / Kania / Albrecht (Eds.) Images of Crime III Kriminologische Forschungsberichte Herausgegeben von Hans-Jörg Albrecht und Günther Kaiser Band K 144 Images of Crime III Representations of Crime and the Criminal Telemach Serassis / Harald Kania / Hans-Jörg Albrecht (Eds.) sdfghjk Duncker & Humblot ! Berlin Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. DOI https://doi.org/10.30709/978-3-86113-096-6 Alle Rechte vorbehalten © 2008 Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften e.V. c/o Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht Günterstalstraße 73, 79100 Freiburg i.Br. http://www.mpicc.de Vertrieb in Gemeinschaft mit Duncker & Humblot GmbH, Berlin http://www.duncker-humblot.de Cover picture: George ’Crime79©’ Ibanez Druck: Stückle Druck und Verlag, Stückle-Straße 1, 77955 Ettenheim Printed in Germany ISSN 1861-5937 ISBN 978-3-86113-096-6 (Max-Planck-Institut) ISBN 978-3-428-13058-0 (Duncker & Humblot) Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem (säurefreiem) Papier entsprechend ISO 9706 Preface Robert Reiner When Ioriginally agreed to write thePrefacefor this third volumeofthe Images of Crime series on ‘Representations of Crimeand the Criminal’, it was my intention to praise avaluable andflourishinginitiative. Yet it seems, sadly, that my role is theob- verse of Shakespeare’s Mark Antony. Icametopraise the series,not to bury it – but unfortunately my role seemstohave become that of valedictorian.The series was valuable and vitallyimportant becauseitembodied aconception of criminologythat has beensomethingofanendangeredspecies in the last three decades of neo-liberal triumphalism, and remains imperilleddespite the weakeningofmarketfundament- alism sincecreditcrunchedlastyear. -

The Reel Prison Experience Melvin Gutterman

SMU Law Review Volume 55 | Issue 4 Article 7 2002 "Failure to Communicate" - The Reel Prison Experience Melvin Gutterman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Melvin Gutterman, "Failure to Communicate" - The Reel Prison Experience, 55 SMU L. Rev. 1515 (2002) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol55/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. "FAILURE To COMMUNICATE ' t THE REEL PRISON EXPERIENCE Melvin Gutterman* I. INTRODUCTION HE academic legal community has failed to appropriately recog- nize the images of law depicted by Hollywood as a legitimate and important subject for scholarly review.' Movies have the capacity to "open up" the discussion of contemporary legal issues that conven- tional legal sources ignore. 2 Although different from the normative legal theory of study, movies provide a rich portrait of popular jurisprudence of legal values.3 A fundamental paradox of many notable films is their inability to simultaneously achieve both scholastic acceptance and artistic achievement, at least equal to other media. 4 Movies are very powerful and can, through the use of provocative images, explore controversial themes and evoke passions that can affect even the most tightly closed minds. 5 The exclusion of films' celebrated images from academic study has its cost. There is, for example, a prevalent belief that life in prison is too t In the most celebrated colloquy in the movie Cool Hand Luke, the Captain as he stands over the defiant convict Luke asserts, "[w]hat we've got here is failure to communicate." What the Captain actually demands is that Luke totally capitulate to the contemptible prison system he embodies.