Competition and Public Service Broadcasting: Stimulating Creativity Or Servicing Capital?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tale of the Brave (Thomas & Friends) Free

FREE TALE OF THE BRAVE (THOMAS & FRIENDS) PDF Reverend Wilbert Vere Awdry | 24 pages | 22 Jul 2014 | Golden Books | 9780385379168 | English | New York, NY, United States Thomas & Friends: Tale of the Brave (Video ) - IMDb From Coraline to ParaNorman check out some of our favorite family-friendly movie picks to watch this Halloween. See the full gallery. With the help of his new friend Gator, Percy learns all about being brave as Thomas spots some suspicious giant footprints at the Sodor Clay Pits. Looking for some great streaming picks? Check out some of the IMDb editors' favorites movies and shows to round out your Watchlist. Visit our What to Watch page. Sign In. Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. Full Cast and Crew. Release Dates. Official Sites. Company Credits. Technical Specs. Plot Summary. Plot Keywords. Parents Guide. External Sites. User Reviews. User Ratings. External Reviews. Metacritic Reviews. Photo Gallery. Trailers and Videos. Crazy Credits. Alternate Versions. Rate This. Director: Rob Silvestri. Added to Watchlist. Halloween Movies for the Whole Family. The Movie List. I watched it. Thomas the tank engine. Use the HTML below. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Photos Add Image Add an image Do you have any images for this title? Edit Cast Credited cast: Mark Moraghan Emily US voice Teresa Gallagher Porter US voice Kerry Shale Edit Storyline With the help of his new friend Gator, Percy learns all about being brave as Thomas spots Tale of the Brave (Thomas & Friends) suspicious giant footprints at the Sodor Clay Pits. -

WILL ING Writer

WILL ING Writer Television 2020- CHANNEL HOPPING WITH JON RICHARDSON 2021 Rumpus Media 2019- THERE’S SOMETHING ABOUT MOVIES 2021 CPL Productions/ Sky1 2018- A LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN 2021 CPL Productions/Sky1 8 OUT OF 10 CATS DOES COUNTDOWN Zeppotron, 2012-19 2019- GOLDIES OLDIES 2020 Viacom 2019 WHAT HAPPENS IF Screen Glue 2017 ZAPPED Co-Creator & Co-Writer (with Paul Powell and Will Ing) of a high-concept series Black Dog Television and Baby Cow Productions for UKTV (2 series) 8 OUT OF 10 CATS Zeppotron/More 4 THE ROYAL VARIETY PERFORMANCE ITV UNSPUN WITH MATT FORDE Avalon (Series 2) BIG STAR’S LITTLE STAR 12 Yard/ITV (Series 4 & 5) A LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN CPL Productions/Sky1 FABLE Pilot script in development with Baby Cow/Microsoft LAST IN LINE Co-Creator & Co-Writer (with Paul Powell and Dan Gaster) of pilot script Black Dog Television / Kudos MY FAMILY AND OTHER IDIOTS Co-Creator & Co-Writer (with Paul Powell and Dan Gaster) of pilot script Black Dog Television NICE GUY EDDIE Co-Creator & Co-Writer (with Paul Powell and Dan Gaster) of pilot script Black Dog Television 2015 8 OUT OF 10 CATS CHRISTMAS SPECIAL Zeppotron/Channel 4 BIG STAR’S LITTLE STAR 12 Yard/ITV WHAT PLANET ARE YOU ON? BBC Earth 2014 YOU SAW THEM HERE FIRST Three Series, ITV RELATIVELY CLEVER Scriptwriter, John Stanley Productions/Sky LIVE AT THE APOLLO Additional material, Open Mike/BBC COMEDY PLAYHOUSE Writing for Victoria Wood WILD THINGS Additional material, IWC Media/Sky 1 OPERATION OUCH Two Series for CBBC/Maverick LET ME ENTERTAIN YOU STV/ITV HOLLYWOOD SQUARES Non-TX Pilot for Group M MARCEL LE CONT SHOW Non-TX Pilot for BBC, 2014 2013 10 O’CLOCK LIVE Two Series, Zeppotron, 2012-2013 SHOW ME THE TELLY ITV HOW TO WIN EUROVISION BBC WHEN MIRANDA MET BRUCE BBC SECRET EATERS Endemol/Channel 4 FAKE REACTION Two Series for STV Productions/ITV, 2011-2013 AND YOU ARE? Co-Creator & Co-Writer, hosted by Miranda Hart. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Pirates Ahoy! Mumfie's Quest #3 by Britt Allcroft Magic Adventures of Mumfie

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Pirates Ahoy! Mumfie's Quest #3 by Britt Allcroft Magic Adventures of Mumfie. Magic Adventures of Mumfie is an animated children's television series and movie, inspired by the works of Katharine Tozer, with an original music score containing more than 22 songs. Created by Britt Allcroft, creator of the Thomas and Friends TV series, narrated by American actor Patrick Breen and directed by John Laurence Collins, Mumfie was first seen in the United States on FOX from 1995 to 1996 in airings of Storytime with Thomas, as part of The Fox Cubhouse . [1] 79 episodes were produced. [2] Contents. Characters Production history Critical reception Other Media VHS releases DVD releases References External links. Characters. Mumfie. The main character of the story, Mumfie is an elephant who lives in a little cottage in the woods. He always expects mail but never receives any. One day he decides to go on an adventure and the first thing he sees is a bird who asks if he can brighten up a dull tree. Scarecrow. When Mumfie first met Scarecrow he was always in a field not ever moving until he set on the quest with him. Scarecrow is with Mumfie in all episodes. Pinkey the Flying Pig. Starting her first appearance in a farm where other pigs bully her, Pinkey is upset because she misses her mother so Scarecrow and Mumfie help her out. The Black Cat. A mysterious, magical cat who riddles Mumfie as he proceeds his journey. Disappearing and reappearing the black cat helps Mumfie in ways he doesn't expect. -

The Story of Thomas the Tank Engine Free

FREE THE STORY OF THOMAS THE TANK ENGINE PDF none | 32 pages | 05 Mar 2015 | Egmont UK Ltd | 9781405276047 | English | London, United Kingdom Strasburg Rail Road The Untold Story of Thomas The Tank Engine She was the first narrator in the franchise. He The Story of Thomas the Tank Engine up the role as narrator of the Railway Series audiobooks after Morris and Rushton retired from the series. He is also known as the longest narrator in the television series from the third series to sixteenth seriestotalling 21 years. Ben Forster played Mr. Perkins and narrated some stories of the Railway Series on the Mr. Perkins' Storytime and Postcards segments. When the show started inBritt Allcroft chose Former Beatles Drummer Ringo Starr as narrator, and he narrated the first two series in and Ringo was also the first ever actor for Mr. Conductor in The Shining Time Station series. He left the show in to focus on his music career and tour with the All The Story of Thomas the Tank Engine Band. He left the show in to pursue his comedy projects. Michael Angelis was the longest narrator in the television series from the third series to sixteenth seriestotaling 21 years. Angelis also re-narrated the Railway Stories originally narrated by Morris and Rushton. He played Percy and James in the working prints for Thomas and the Magic Railroadbut was later replaced by Susan Roman and Linda Ballantyne respectively because the American test audience thought that he made the characters sound old. He played Mr. Conductor in Thomas and the Magic Railroadand he was in charge of it instead because the narration originally played by adult Lily was The Story of Thomas the Tank Engine. -

Thomas & Friends™ Engine

Thomas & Friends™ Engine DecoSet® #30055 (6/Pkg) Thomas & Friends is a trademark of Gullane Entertainment Inc. A BRITT ALLCROFT COMPANY PRODUCTION. #30052 ©2008 DecoPac ©2008 Gullane (Thomas) Limited. Thomas and Friends™ Engine DECORATING DIRECTIONS: 1. Ice cake light Royal #9139 “R” & “R”. Blue #9507. 6. Using tip #8, pipe Royal Blue 2. Using tip #2B, pipe White #9507 borders. bands around sides of the 7. Using tip #6, pipe Leaf Green cake and top of cake #9516 grass. as shown. 8. Place DecoSet® item on cake 3. Using tip #3, pipe Red Red as shown. #9139 tracks on bottom 9. Place warning sticker on band and top of cake. outside of cake box. 4. Using tip #4, pipe Lemon Yellow #9505 rails and *Recommend using #11161 – railroad crossing sign. Round cutter to create Petite 5. Using tip #3, pipe Red Red Signature Cake. DIRECCIONES para DECORAR: 1. Esparza la crema Azul Royal 5. Use la punta (dulla) #3 con claro #9507 sobre el pastel. el color Rojo Rojo #9139 2. Use la punta (dulla) #2B con para hacer los “R” y “R”. el color Blanco para hacer 6. Use la punta (dulla) #8 con las bandas alrededor de los el color Azul Royal #9507 lados del pastel y en la parte para decorar los bordes. superior así como se muestra. 7. Use la punta (dulla) #6 con 3. Use la punta (dulla) #3 el color Verde Hoja #9516 con el color Rojo Rojo para hacer el pasto. #9139 para dar forma a los 8. Coloque el artículo del carriles en la parte inferior y DecoSet® encima del pastel superior del pastel. -

Product Guideguide

MIPT V PRODUCTPRODUCT GUIDEGUIDE LOVE CRUISE 2001CHRIS COLORADO 2 222 FBC A AAA Animation (6x26’) Reality Series (7 x 60min.) Language: French (original version), Cast: Sixteen Eligible Singles Dubbed English, 20TH CENTURY FOX Exec. Prods. Jonathan Murray, Mary- A&E Director: Franck Bertrand, Thibaut INTERNATIONAL Ellis Bunim Arts & Entertainment, A&E Television Chatel, Jacqueline Monsigny Audiences will cruise through the south- Network / The History Channel, 235 East Produced by: AB Productions and TELEVISION ern Caribbean and visit exotic enezuelan 45th Street, New York, NY 10017 USA. Studios Animage 20th Century Fox International ports with eighteen eligible single men Tel: 212.210.1400. Fax: 212.983.4370. Co-producers: MEDIASET /CANAL + / Television, P.O. Box 900, Beverly Hills, and women who are in competition to find At MIP-TV: Carl Meyer (Regional France 3 / AB PRODUCTIONS CA 90213-0900. Tel 310.369.1000. love and to gain an extraordinary grand Managing Director, Asia), Chris O’Keefe Delivery Status: Completed Australia Office: 20th Century Fox prize. (Regional Managing Director, Latin Budget: 43 MF International TV, Level 5, Frank Hurley KATE BRASHER America), Shelley Blaine Goodman (VP, Danger lurks, group of 666’ agents, have Grandstand, Fox Studios Australia. CBS Affiliates Sales, Canada), Maria infiltrated the higher levels power of the Driver Avenue, Moore Park NSW 1363, Drama (6 x 30 min.) Komodikis (SVP, International Managing world federation. Chris Colorado becomes Australia. Tel 61.2.8353.2200. Fax Cast: Mary Stuart Masterson, Rhea Director) the President’s man to save democracy and 61.2.8353.2205. Brazil Office: Fox Film Perlman, and Hector Elizondo Office: E3-08 peace. -

Business Valuation Management

FINAL GROUP - IV PAPER - 18 BUSINESS VALUATION MANAGEMENT The Institute of Cost and Works Accountants of India 12, SUDDER STREET, KOLKATA - 700 016 First Edition : January 2008 Revised Edition : March 2009 Published by: Directorate of Studies The Institute of Cost and Works Accountants of India 12, SUDDER STREET, KOLKATA - 700 016 Printed at : Repro India Limited, 50/2, TTC MIDC Industrial Area, Mahape, Navi Mumbai - 400 710, India Copyright of these Study Notes in reserved by the Institute of Cost and Works Accountants of India and prior permission from the Institute is necessary for reproduction of the whole or any part thereof. BUSINESS VALUATION MANAGEMENT A Note to the Student: Business Valuation Management is a fascinating subject, as it, foremost, provides (and also warrants) the most comprehensive analysis of a business model. It perforce enjoins upon the business valuer to delve into the depths of the business that is being valued and come to grips with the macro and micro, technical and ! nancial, the short and longer term aspects of the business. This book attempts to provide the following to you: • An easy introduction to the concept of business valuation • A complete overview of the existing business valuation models • An understanding of the importance of various assumptions underlying the valuation models • An easy-to-understand explanation of various business valuation techniques, with their pros and cons • A discussion on valuation of assets and liabilities, whether tangible or intangible, apparent or contingent. • Application of the concepts in real-life situations, with many examples. The design and structure of the book are such that the book can provide vital insights into the key issues in business valuation, suitably enhanced with many scholastic articles that can not only provide the depth, but also bring out the complexities involved in business valuation. -

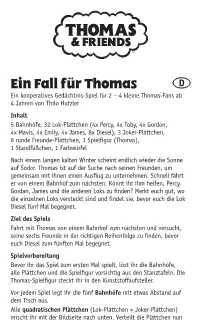

Ein Fall Für Thomas

Ein Fall für Thomas D Ein kooperatives Gedächtnis-Spiel für 2 – 4 kleine Thomas-Fans ab 4 Jahren von Thilo Hutzler Inhalt 5 Bahnhöfe, 32 Lok-Plättchen (4x Percy, 4x Toby, 4x Gordon, 4x Mavis, 4x Emily, 4x James, 8x Diesel), 3 Joker-Plättchen, 6 runde Freunde-Plättchen, 1 Spielfigur (Thomas), 1 Standfüßchen, 1 Farbwürfel Nach einem langen kalten Winter scheint endlich wieder die Sonne auf Sodor. Thomas ist auf der Suche nach seinen Freunden, um gemeinsam mit ihnen einen Ausflug zu unternehmen. Schnell fährt er von einem Bahnhof zum nächsten. Könnt ihr ihm helfen, Percy, Gordan, James und die anderen Loks zu finden? Merkt euch gut, wo die einzelnen Loks versteckt sind und findet sie, bevor euch die Lok Diesel fünf Mal begegnet. Ziel des Spiels Fahrt mit Thomas von einem Bahnhof zum nächsten und versucht, seine sechs Freunde in der richtigen Reihenfolge zu finden, bevor euch Diesel zum fünften Mal begegnet. Spielvorbereitung Bevor ihr das Spiel zum ersten Mal spielt, löst ihr die Bahnhöfe, alle Plättchen und die Spielfigur vorsichtig aus den Stanztafeln. Die Thomas-Spielfigur steckt ihr in den Kunststoffaufsteller. Vor jedem Spiel legt ihr die fünf Bahnhöfe mit etwas Abstand auf dem Tisch aus. Alle quadratischen Plättchen (Lok-Plättchen + Joker-Plättchen) mischt ihr mit der Bildseite nach unten. Verteilt die Plättchen nun so auf die Bahnhöfe, dass um jeden Bahnhof herum sieben Plättchen verdeckt liegen. Die Spielfigur stellt ihr auf einen beliebigen Bahnhof. Die sechs runden Freunde-Plättchen mischt ihr ebenfalls verdeckt. Dann deckt ihr sie nacheinander auf und legt sie in der aufgedeckten Reihenfolge nebeneinander. -

Mark Kermode Funders

13TH BRISTOL INTERNATIONAL SHORT FILM FESTIVAL WEDNESDAy 21 – SUNDAY 25 NOVEMBER 2007 WATERSHED UK BOX OFFICE +44 (0) 117 927 5100 WWW.ENCOUNTERS-FESTIVAL.ORG.UK “THE PLACE TO DISCOVER NEW Talent” MARK KERMODE FUNDERS PRINCIPAL SPONSORS PARTNERS CONTENTS Welcome Competition Screenings Introduction 3 South West Showcase 38 – 39 Information 7 International Panorama 1 40 – 41 Calendar 8 – 9 International Panorama 2 42 International Panorama 3 43 Delegates Information International Panorama 4 44 Delegates Information 12 International Panorama 5 45 Added Attractions 13 International Panorama 6 46 Film School: The Producers Story 14 International Panorama 7 47 Animation Industry Day 15 Best of British 1 48 – 49 Best of British 2 50 Special Events & Awards Best of British 3 51 Opening Highlights 21 Emerging Talent 1 52 – 53 Persepolis Feature Preview 22 Emerging Talent 2 54 – 55 Where’s The Bunny Ronnie? 23 Children’s Jury Award 56 – 57 4:30 23 Animate Award 58 – 59 Desert Island Flicks 24 Late Lounge 60 – 61 Kodak Cinematography Masterclass 24 DepicT! Showcase 62 – 63 BAFTA Short Film Paradise 25 Special Events 26 Guest Screenings Events for Kids 27 Super-8 Cities 68 – 69 Awards 28 – 29 Singapore Showcase 70 – 71 Juries 30 – 31 BBC Three New Film Makers Award 72 – 73 Canon of UK Short Film 74 – 75 Out of Control: Freeform Filmmaking 76 – 77 NAHEMI Student Shorts 78 – 79 UK Film Council’s Digital Generation 80 – 81 Canada Calling 82 Cinema Extreme 83 Shorts from Sweden 84 The Audi Channel Reel Talent Award 85 B3 Showcase 86 BBC New Music Shorts 87 Animate Commissions 88 Short Matters!1 89 Short Matters!2 90 Information Film Index 92 Film Contacts 93 – 96 Acknowledgements & Thanks 100 1 GBRICK FP ENCOUNTER AD 9.06_3 7/9/06 11:33 am Page 1 DISCOVER GOLDBRICK HOUSE EAT IN THE CAFÉ/BAR OR RESTAURANT DRINK IN THE CHAMPAGNE & COCKTAIL BAR, LIBRARY OR STUDY café/bar . -

A1 Gordon Is Proud – He's the Fastest Steam Engine on the Island Of

Thomas the Tank Engine & Friends Thomas the Tank Engine & Friends Based on The Railway Series by The Reverand W Awdry D'après The Railway Series de The Reverand W Awdry ©2004 Gullane (Thomas) Limited. Thomas & Friends is a trademark © 2004 Gullane (Thomas) Limited. Thomas & Friends est une marque of Gullane Entertainment Inc. A HIT Entertainment Company. de Gullane Entertainment Inc. Une entreprise HIT Entertainment. e f A1 Gordon is proud – he’s the fastest steam engine on the Island of Sodor. A1 Gordon est très fier, il est la locomotive la plus rapide de l’île de Sodor. A2 Sir Topham Hatt sends Thomas to pick up a jet engine and deliver it A2 Sir Topham Hatt envoie Thomas chercher un moteur à réaction qu’il devra to the airfield. livrer au terrain d’aviation. A3 The switch is knocked and the jet engine is turned on. A3 L’interrupteur est enclenché et le moteur tourne. A4 The engine begins to whine and sends Thomas rocketing down the track. A4 Le moteur commence à vrombir et voilà Thomas qui fonce sur la voie ferrée. A5 The driver tries to put on the brakes. "Oh, no, it’s a runaway train!" A5 Le chauffeur tente d’appliquer les freins. « Oh non, le train s’est emballé ! » A6 Because of the jet engine, Thomas is faster than all of the other trains… A6 Avec le moteur à réaction, Thomas est plus rapide que tous les autres trains… A7 …even Gordon! A7 …Même Gordon! B1 Sir Topham Hatt informs the engines that there will be no more washdowns. -

Each of RC2 and HIT Entertainment Is Treated Here for Convenience As a Singular Noun

Case: 1:04-cv-06927 Document #: 149 Filed: 01/29/08 Page 1 of 16 PageID #:<pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION DANIEL P. SCHROCK, etc., ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) No. 04 C 6927 ) LEARNING CURVE INTERNATIONAL, INC.,) et al., ) ) Defendants. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Daniel Schrock d/b/a Dan Schrock Photography (“Schrock”), a Chicago-based professional photographer, has brought this action against a web of corporate defendants--a web that is best untangled by carving out two groupings. First, Schrock complains against the “RC2” defendants (for convenience referred to collectively by the “RC2” name), comprising Learning Curve International, Inc., RC2 Corporation and RC2 Brands, Inc. Learning Curve International, Inc. is a distributor of children’s toys that was acquired in early 2003 by Racing Champions Ertl Corporation, which later changed its name to RC2 Corporation. RC2 Brands, Inc., a designer, producer and marketer of children’s toys and collectibles, is a subsidiary of RC2 Corporation. As for the second group of corporate defendants (for convenience referred to collectively as “HIT Entertainment”1), it comprises Gullane Entertainment, Inc., Gullane Thomas Limited, Thomas 1 Each of RC2 and HIT Entertainment is treated here for convenience as a singular noun. Case: 1:04-cv-06927 Document #: 149 Filed: 01/29/08 Page 2 of 16 PageID #:<pageID> Licensing LLC and HIT Entertainment, PLC (all are predecessors, subsidiaries or affiliates of HIT Entertainment Limited). Schrock complains of copyright infringement by both RC2 and HIT Entertainment and breach of bailment and conversion by RC2. Each of the two sets of defendants has, with trial looming (at long last!), moved for summary judgment under Fed. -

Britt Allcroft

OnLine Case 3.3 Britt Allcroft Britt Allcroft, who became a producer of television programmes, went to the same school at the same time as Anita Roddick, founder of The Body Shop. She always had a passion for storytelling. In her younger days she wrote several short stories, but none of them was ever published. Instead she found her way into television, and in 1978 she was asked to make a film about the British passion for steam engines. There can be few better-loved children’s characters than Thomas the Tank Engine, created originally by the Reverend W. Awdry in his spare time. As well as this series of illustrated books for children, Awdry wrote serious, adult books on steam railways. Although the Thomas books were no longer enjoying the popularity they initially had, Awdry was invited to appear in the film. He agreed, but inclement weather held up the project for several days. Awdry and Allcroft spent two days talking to each other. Although others had tried unsuccessfully to animate Awdry’s characters – essentially a fleet of steam engines with distinctive faces and personalities – Britt Allcroft became determined to succeed where others had failed. You need courage when people tell you are off your head . Thomas is much more than just a steam train having adventures – it is a way of life for me. Together with her business partner, who at the time was her husband, she approached venture capitalists, but the general reaction was that the time for Thomas had passed. Eventually, a bank loan from Barclays, supplemented by a second mortgage, allowed her to agree a licensing deal with publishers Reed Elsevier, who owned the master rights to the character, and to make her first film, which was broadcast on network television in 1984.