The Writings of John Muir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ley, So the Still Deeper Cañon of Lower Two Miles,That Is, Beyond Rather Than

THE CANON OF YOSEMITE 87 As Merced Cañon forms the southeast branch of Yosemite Val- ley, so the still deeper cañon of Tenaya Creek isits northeastern arm.Here the glacial story is less plain, and on first sight, from the heights on either side, it might be overlooked.For above the cañon's lower two miles,that is, beyond the foot of Mt. Watkins,it crowds to a narrow box-cañon between that great cliff and the steep incline of Clouds Rest.This might seem to be a V-shaped, stream-cut gorge, rather than to have the broader bottom commonly left by a glacier. But alittle exploration discovers glacial footprints in the terminal moraines and the lakes and filled lake-beds,withfineconnecting waterfalls, that mark aglacier's descent from the Cathedral Peak Range, south of the Tuolumne. We Overhung at Summit of the Half Dont,-. nrart have hardly entered the cañon, in- a tulle above the Valley floor nn.l Tena-u deed, before we are reminded of (allan.El Caption Is seen in the tllatanee. El Capitan moraine and the enclosed Yosemite Lake. A similar boulder ridge, thrown across the cañon here, is traversed by the road as it carries visitors on their early morning trips to see the sunrise reflections in Mirror Lake.This lakelet evidently occupies the lowermost of the glacial steps.It is a mere reminder of its former size, the delta of Tenaya Creek having stolen a mile from its upper end.Farther up the cañon, below and above Mt. Watkins, stream sediment has already turned similar lakes into meadows. -

Yosemite National Park National Park Service

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Yosemite National Park Tuolumne Wild and Scenic River Comprehensive Management Plan Draft Environmental Impact Statement Tuolumne River Values and Baseline Conditions After five years of study and stakeholder involvement, the Tuolumne Wild and Scenic River Comprehensive Management Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Statement (Tuolumne River Plan/DEIS) will be released in summer of 2011. In advance of the plan’s release, the NPS is providing the Tuolumne River Values and Baseline Conditions chapter as a preview into one of the plan’s most foundational elements. Sharing the baseline information in advance of the plan will give members of the public an understanding of river conditions today and specific issues that will be explored in the Tuolumne River Plan. Public comments on all elements of the Tuolumne River Plan, including the baseline conditions chapter, will be accepted when it is released for review this summer. What follows is a description of the unique values that make the Tuolumne stand apart from all other rivers in the nation. This chapter also provides a snapshot in time, documenting overall conditions and implications for future management. In particular the baseline chapter examines, • What are the outstandingly remarkable values that make the Tuolumne River worthy of special protection under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (WSRA)? • What do we know about the condition of these values (in addition to water quality and free-flow), both at time of designation in 1984 and -

Yosemite Guide Where Togo and What Todoin Yosemite National Park May-June 2010 Experience Your Americayosemite Nationalpark

after a major snowfall. major a after G 83 Note: Service to stops 15, 16, 17, and 18 may stop stop may 18 and 17, 16, 15, stops to Service Note: Third Class Mail Class Third Postage and Fee Paid Fee and Postage US Department Interior of the posted signs. signs. posted to rockfall. Please observe observe Please rockfall. to Mirror Lake is closed due due closed is Lake Mirror A portion of the trail past past trail the of portion A May 26 - June 29, 2010 29, June - 26 May Guide Yosemite Park National Yosemite America Your Experience US Department Interior of the Service Park National 577 PO Box CA 95389 Yosemite, Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Vol. 35, Issue No.4 Inside: 01 Things to Do 02 Park Overview 05 Yosemite Valley 08 Wawona, Glacier Pt. 10 Tuolumne Meadows 16 Camping 17 Hiking May-June 2010 Clark Range, from Glacier Point. Photo by Christine White Loberg Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park May 26 - June 29, 2010 Yosemite Guide Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Yosemite Guide May 26 - June 29, 2010 Things to Do Keep this Guide with you to get the most out of your visit hat do you want to do with Valley” for a wild ride through your special time in the universe to learn about stars, WYosemite? The choice is constellations, planets, meteors, and yours, but to give you some ideas, park other night sky features, all from the rangers made a list of possibilities for comfort of Yosemite Valley. -

Fairview Dome

V4DIFMITF NATURE NOTES ,,,_, ._. VOL . XX March, 1941 No . 3 FAIRVIEW DOME Yosemite -Nature Notes THE PUBLICATION OF THE YOSEMITE NATURALIST DEPARTMENT AND THE YOSEMITE NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION Published Monthly VOL . XX MARCH, 1941 NO . 3 FAIRVIEW DOME By Ranger Naturalist Carl W. Sharsmith Fairview Dome (9737 feet altitude) Tuolumne Meadows by the road, is the highest of the Tuolumne Mea- numerous bear trails are crossed, dows domes, and affords a thrilling one of which contours along the hill yet perfectly safe climb, but it has and is for some distance as graded been much neglected by Tuolumne and well-beaten as a much used Meadows hikers. This is no doubt man-made trail . Elsewhere along it, due to its sheer and unclimbable ap- in common with the other trails, deep pearance as seen from the Tioga impressions mark the footfalls, since Road along which it is adjacent . It the bears usually step each in the lies to the right when driving east, same tracks. The reasons for these dominating one's view here just be- numerous bear trails is, of course, fore the road drops downgrade in because of the proximity to the local entering the lower end of Tuolumne garbage pits. Meadows . A day off was spent by In approaching the dome in this the writer in ascertaining the feasi- fashion, one eventually skirts the bility of leading a group to its sum- very base of the massive cliff along mit, and a safe means of ascending a natural pathway between it and it was found . Since then two enthu- fine groves of Mountain Hemlocks siastic parties were led to the sum- and occasional fine specimens of mit, with the unanimous acclaim Western White Pine and Red Fir. -

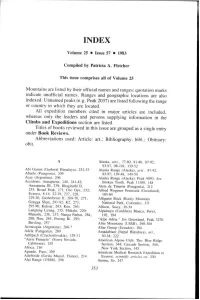

Mountains Are Listed by Their Official Names and Ranges; Quotation Marks Indicate Unofficial Names

INDEX Volume 25 0 Issue 57 0 1983 Compiled by Patricia A. Fletcher This issue comprises al1 of Volume 25 Mountains are listed by their official names and ranges; quotation marks indicate unofficial names. Ranges and geographic locations are also indexed. Unnamed peaks (e.g. Peak 2037) are listed following the range or country in which they are located. All expedition members cited in major articles are included, whereas only the leaders and persons supplying information iti the Climbs and Expeditions section are listed. Titles of books reviewed in this issue are grouped as a single entry under Book Reviews. Abbreviations used: Article: art.; Bibliography: bibl.; Obituary: obit. A Alaska, arts., 77-80, 81-86, 87-92, 93-97, 98-101; 139-52 Abi Gamin (Garbwal Himalaya), 252-53 Alaska Range (Alaska), arts.. 87-92, Abuelo (Patagonia), 209 93-97; 139-48, 149-50 Acay (Argentina), 206 Alaska Range (Alaska): Peak 9050. See Accidents: Annapuma, 240, 241-42; Broken Tooth. Peak 11300, 148 Annapuma III, 239; Bhagirathi II, Aleta de Tiburbn (Patagonia), 212 253; Broad Peak, 271; Cho Oyu, 232; Alfred Wegener Peninsula (Greenland), Everest, 8-14. 22-29, 227, 228, 183-84 229-30; Gasherbrum II, 269-70, 271; Alligator Rock (Rocky Mountain Gongga Shari,, 291-92; K2, 273, National Park, Colorado), 171 295-96; Kuksar, 283; Kun, 265; Allison, Stacy, 30-34 Langtang Lirung, 235; Makalu, 220; Alpamayo (Cordillera Blanca, Peru), Manaslu, 236, 237; Nanga Parbat, 284, 192, 194 288; Nun, 263. Porong Ri, 295; “Alpe Adria.” See Greenland, Peak 3270. Shivling, 257 Altai Mountains (USSR), 298-300 Aconcagua (Argentina), 206-7 Altar Group (Ecuador), 184 Adela (Patagoma), 209 Amadablam (Nepal Himalaya), an., AdrSpach (Czechoslovakia), 129-3 1 30-34; 222 “Aene Pinnacle” (Sierra Nevada, American Alpine Club, The: Blue Ridge California), 155 Section. -

The Far Side of the Sky

The Far Side of the Sky Christopher E. Brennen Pasadena, California Dankat Publishing Company Copyright c 2014 Christopher E. Brennen All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language or computer language, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission from Christopher Earls Brennen. ISBN-0-9667409-1-2 Preface In this collection of stories, I have recorded some of my adventures on the mountains of the world. I make no pretense to being anything other than an average hiker for, as the first stories tell, I came to enjoy the mountains quite late in life. But, like thousands before me, I was drawn increasingly toward the wilderness, partly because of the physical challenge at a time when all I had left was a native courage (some might say foolhardiness), and partly because of a desire to find the limits of my own frailty. As these stories tell, I think I found several such limits; there are some I am proud of and some I am not. Of course, there was also the grandeur and magnificence of the mountains. There is nothing quite to compare with the feeling that envelopes you when, after toiling for many hours looking at rock and dirt a few feet away, the world suddenly opens up and one can see for hundreds of miles in all directions. If I were a religious man, I would feel spirits in the wind, the waterfalls, the trees and the rock. Many of these adventures would not have been possible without the mar- velous companionship that I enjoyed along the way. -

Fairview Dome's West Face

Fairview Dome’s West Face T h o m a s H ig g in s S EVERAL times since 1968, Bob Kamps and I have attempted a new route on the virgin west face of Fairview Dome in Tuolumne Meadows, the glorious Sierra high country above Yosemite.1 Each time, we retreated after realizing aid would prob ably be necessary to surmount a twenty-foot overhang dead center on the proposed line. In the past two years, several parties have ventured onto the face (see marked attempts), but have been stopped by bulging roofs or smooth, high-angle rock. In September of 1973, Mike Irwin and I re climbed the pitches Bob and I had completed several years before, found a way around the enormous roofs and gained the summit. The route proved to be one of the most lengthy and improbable in all of Tuolumne. The many granite domes of Tuolumne Meadows are gradually attract ing more and more climbers, though the scarcity of routes below 5.8 and the lack of a formal guidebook probably holds back a climbing flood. The Tuolumne Rock Climbing School continues to receive considerable demand for its service. Anticipating the damage to rock such a demand might do, the school now instructs all its enrollees in the use of nuts. New routes continue to be done, mostly of the short and difficult variety. Steve Roper promises a technical guide to the Sierra, including Tuolumne Meadows, amid a growing debate about the tendency for climbing guide books to bring excessive crowding to climbing areas. -

Mountains Are Listed by Their Official Names and Ranges; Quotation Marks Indicate Unofficial Names

INDEX Volume 28 l Issue 60 l 1986 Compiled by Patricia A. Fletcher This issue comprises all of Volume 28 Mountains are listed by their official names and ranges; quotation marks indicate unofficial names. Ranges and geographic locations are also in- dexed. Unnamed peaks (e.g., Peak 2037) are listed following the range or country in which they are located. All expedition memberscited in major articles are included, whereas only the leaders and persons supplying information in the Climbs and Expeditions section are listed. Titles of books reviewed in this issue are grouped as a single entry under Book Reviews. Abbreviations used: Article: art.; Bibliography: bibl.; Obituary: obit. A Aconcagua (Argentina), 112, 114, 197-200; parachute descent of, 200 Abi Gamin (Garhwal Himalaya), 253 Adams, B., 114 Abra (Cordillera de Potosi, Bolivia), Adams, W., 114 196 Adlok Peak (Baffin Island), 185 Abrego, Mari, 293-95 Aeolian Tower (Utah), 168 Acay (Argentina), 197 Agssuassat (Greenland), 186 Accidents: Aconcagua, 200; Ama Dablam, Agua Blanca (Culata, Sierra de la, 22 1; Annapuma Dakshin, 245; Broad Venezuela), 187 Peak, 269; Denali, 140, 141; Everest, Airport Tower. See Aeolian Tower. 227-28, 29.5, 298-99; Garhwal, Peak Alaska, arts., 57-63, 65-68, 69-72; 139-5 1 6131, 257; Gaurishankar, 236; Gurja Alaska Range, arts., 57-63, 65-68, 69-72; Himal, 251; Himalchuli, 240; K2, 268, 139-45, 147 271; Kamet, 252; Kang Guru, 242; Alaska Range: Peak 5350, 147; Peak 6210, Kangchenjunga, 215; Kangchungtse, 147; Peak 6290, 147; Peak 7290, 147 219-20; Langtang Lirung, -

Bseaite a JOURNAL for MEMBERS of the YOSEMITE ASSOCIATION

bseAite A JOURNAL FOR MEMBERS OF THE YOSEMITE ASSOCIATION Fall 1996 Volume 58 Number 4 The Ground Shook and the Sky Fell THE GROUND SHOOK AND THE SKY FELL BY JIM SNYDER Two rockfalls occurred in Yosemite Valley just seconds at 6 :54 p.m." The dust came quickly, "like a tornado" apart at 6:52 p.m. on Wednesday, July 10, 1996.The impact according to one visitor, enveloping Happy Isles, the killed one young man and injured a number of other peo- nearby trails, and much of Upper Pines Campground. ple, some seriously. Two lesser rockslides followed early in Camper Roger Johnson saw the dust as "a solid wall, a the morning of July 11 to complete the collapse of a very boiling wall of gray." "It turned black, you could not see irregular granite arch on the rim of the valley some 2,000 anything," Gisele Rue recalled. The dust hung in the air feet above Happy Isles . Although some people witnessed around Happy Isles for hours afterwards, limiting visibil- the first two blocks breaking loose and falling, what most ity and hampering search and rescue efforts. Searcher people noticed was the sound and the dust. John Brenner of the Sacramento Fire Department said, There were those who associated the sound with an "It's like being in a dust storm and searching for a needle earthquake. Yosemite's Deputy Superintendent Hal in a haystack "' Grovert was out for a run when he thought he heard A typical rockslide in Yosemite Valley has a much dif- thunder, although it seemed awfully close . -

Superintendent's Annual Report

SUPERINTENDENT'S ANNUAL REPORT YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK 1991 SUPERINTENDENT'S ANNUAL REPORT YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK 1991 1991 HIGHLIGHTS January o The year 1991 was the fifth year of o Feb. 18—Chad Austin Youngs, age 17, of drought. Davis, CA, was killed while scrambling above Sunnyside Campground. o Jan. 8~The announcement was made that the park concessioner YP&CCo. was sold o Feb. 19—Bear, mosquito, and to the National Park Foundation effective yellow jacket activity is noticed, all on Feb. 1. unseasonably early. o Jan. 16—Community Peace Project o Feb. 25—Foresta homeowners met with Against War in Gulf demonstrated in El NPS Director Ridenour, Secretary of the Portal and called their campaign "No Interior Lujan, and National Inholders Blood for Oil." Association President Cushman in Washington. o Jan. 20—Mariposa Grove closed for three weeks due to hazard-tree removal. o Feb. 28—March 5—A major storm brought relief to drought-stricken Sierra. On o Jan. 22—Western Regional Director March 4, 7.92" of rain was received. Stanley Albright decided to permit rebuilding in Foresta if landowners meet March all county sanitation codes. o March 21-Four special-use permit o Jan. 28~Badger Pass closed due to lack of holders in Foresta were given a 90-day snow. It reopened and closed again on notice to vacate the premises. Feb. 19. o March 27—A 40-ton boulder closed Big February Oak Flat Road from Crane Flat to the El Portal Road at the dam. o Chief Ranger Roger Rudolph transferred to Olympic National Park, and Chief of April Concessions Wayne Schulz retired from the park service and began working for o April 1-Ticketron outlets closed north of the Mariposa Chamber of Commerce. -

Climb the Mountains and Get Their Good Tidings. Nature's Peace Will

CALIFORNIA DREAMING “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves” John Muir John Muir’s influence is everywhere in the Yosemite Valley and also in the Meadows of Tuolomne. His vision is apparent in the trail that bears his name and implicit in the way the National Park is run. You won’t get a phone signal, wifi is elusive, and there is evidence everywhere of conservation efforts – stick to the trails, stay off areas under restoration, keep to the low speed limits to protect wild-life. Of course you can also get John Muir books, fridge magnets, tee shirts and all the usual paraphernalia but he has fully earned his place in the history of this wonderful area which was declared a National Park as early as 1864. In the Tuolomne Meadows there is a very strong free climbing ethic of which I’m sure John Muir would approve. There is the occasional old peg. There are very occasional bolted stances on great expanses of featureless granite where, without some sort of contrived stance, pitches could be 100 metres long. But, in essence for most climbs, you can take only photos and leave the rock pristine. There are fewer peg scars here than in the Valley and these often make possible free ascents of previously aided climbs. I had climbed in the Valley in 1998 but our plans to spend time in the Tuolomne Meadows were thwarted by the closure of the Tioga Pass road – Highway 120. -

MILEAGE TABLE Time Shown in Minutes; Distance Shown in Miles Hwy

MILEAGE TABLE Time shown in minutes; distance shown in miles Hwy. 140 West from Mariposa (Hwy. 49 South & Hwy. 140) Time Time (total) Distance (total) Yaqui Gulch Rd. 5 5 4 Mt. Bullion Cutoff Rd. 4 9 7.2 Hornitos Rd. 6 15 11.7 Old Highway 3 18 14.2 Chase Ranch 6 24 18.8 Merced County line 4 28 21.2 Cunningham Rd. 1 29 22.2 Planada (at Plainsburg Rd.) 5 34 28.8 Merced and Highway 99 11 45 37.4 Hwy. 140 East from Mariposa (Hwy. 49 South & Hwy. 140) Time Time (total) Distance (total) Hwy. 49 North & Hwy.140 (four way stop) 2 2 0.9 E Whitlock Rd. 4 6 4.1 Triangle Rd. 2 8 5.1 Carstens Rd. 2 10 7.2 Colorado Rd. 2 12 8.6 Yosemite Bug 2 14 10 Briceburg 4 18 12.7 Ferguson Slide 10 28 20.8 South Fork Merced River* 2 30 21.9 Indian Flat Campground* 5 35 24.5 Foresta Rd. at bridge* 5 40 26.8 Foresta Rd. at 'old' El Portal* 2 42 28 YNP Arch Rock Entrance* 6 48 31.5 Big Oak Flat Rd.* 9 57 36.5 Wawona Rd.* 2 59 37.4 Hwy. 49 South from Mariposa (Hwy. 49 South & Hwy. 140) Time Time (total) Distance (total) County Fairgrounds 2 2 1.7 Silva Rd. / Indian Peak Rd. 3 5 4.5 Darrah Rd. 1 6 5.3 Woodland Rd. and Hirsch Rd. 3 9 7.7 Usona Rd. and Tip Top Rd. 2 11 9.6 Triangle Rd.