Who Owns History? the Construction, Deconstruction, and Purpose of the Main Line Myth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

America Enters WWI on April 6, 1917 WW I Soldiers and Sailors

America enters WWI on April 6, 1917 WW I Soldiers and Sailors associated with Morris County, New Jersey By no means is this is a complete list of men and women from the Morris County area who served in World War I. It is a list of those known to date. If there are errors or omissions, we request that additions or corrections be sent to Jan Williams [email protected] This list provides names of people listed as enlisting in Morris County, some with no other connection known to the county at this time. This also list provides men and women buried in Morris County, some with no other connection known to the County at this time. Primary research was executed by Jan Williams, Cultural & Historic Resources Specialist for the Morris County Dept. of Planning & Public Works. THE LIST IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER WW I Soldiers and Sailors associated with Morris County, New Jersey Percy Joseph Alvarez Born February 23, 1896 in Jacksonville, Florida. United States Navy, enlisted at New York (date unknown.) Served as an Ensign aboard the U.S.S. Lenape ID-2700. Died February 5, 1939, buried Locust Hill Cemetery, Dover, Morris County, New Jersey. John Joseph Ambrose Born Morristown June 20, 1892. Last known residence Morristown; employed as a Chauffer. Enlisted July 1917 aged 25. Attached to the 4 MEC AS. Died February 27, 1951, buried Gate of Heaven Cemetery, East Hanover, New Jersey. Benjamin Harrison Anderson Born Washington Township, Morris County, February 17, 1889. Last known residence Netcong. Corporal 310th Infantry, 78th Division. -

2013 Appraisal

Integra Realty Resources Philadelphia Appraisal of Real Property Three Portions of The Ardrossan Farm Estate Residential Land Parcels A, B, C located along Darby-Paoli Road and Newtown Road Radnor Township (Villanova P.O.), Delaware County, Pennsylvania 19085 Prepared For: Radnor Township Administration Effective Date of the Appraisal: January 9, 2014 Report Format: Summary IRR - Philadelphia File Number: 131-2013-1099 Three Portions of The Ardrossan Farm Estate Parcels A, B, C located along Darby-Paoli Road and Newtown Road Radnor Township (Villanova P.O.), Delaware County, Pennsylvania Integra Realty Resources Address 1 T Office Phone Office Name Address 2 F Office Fax Address 3 Office Email www.irr.com January 15, 2014 Mr. Robert Zienkowski Radnor Township Administration Office 301 Iven Avenue Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087 SUBJECT: Market Value Appraisal Three Portions of The Ardrossan Farm Estate Parcels A, B, C located along Darby-Paoli Road and Newtown Road Radnor Township (Villanova P.O.), Delaware County, Pennsylvania 19085 IRR - Philadelphia File No. 131-2013-1099 Dear Mr. Zienkowski: Integra Realty Resources – Philadelphia is pleased to submit the accompanying appraisal of the referenced property. The purpose of the appraisal is to develop an opinion of the market value of the fee simple interest in the real property. The client for the assignment is Radnor Township Administration Office, and the intended use is for the potential acquisition of the subject parcels by Radnor Township, for the purpose of open space preservation. The appraisal is intended to conform with the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP), the Code of Professional Ethics and Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice of the Appraisal Institute, and applicable state appraisal regulations. -

RG3.9 John Cummins Edwards, 1844

Missouri State Archives Finding Aid 3.9 OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR JOHN CUMMINS EDWARDS, 1844-1848 Abstract: Records (1844-1848) of Governor John Cummins Edwards (1804-1888) include correspondence, petitions, proclamations, and reports. Extent: 0.4 cubic feet (1 Hollinger) Physical Description: Paper ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION Access Restrictions: No special restrictions. Publication Restrictions: Copyright is in the public domain. Preferred Citation: [Item description], [date]; John Cummins Edwards, 1844-1848; Office of Governor, Record Group 3.9; Missouri State Archives, Jefferson City. Processing Information: Processing completed by Becky Carlson, Local Records Field Archivist, on March 11, 1996. Finding aid updated by Sharon E. Brock on August 5, 2008. HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES John Cummins Edwards was born on June 24, 1804 in Frankfort, Kentucky to John and Sarah Cummins Edwards but was raised near Murfreesboro, Tennessee. He completed preparatory studies at Black’s College, Kentucky; and studied law at Dr. Henderson’s Classical School in Rutherford County, Tennessee . Edwards was admitted to the Tennessee Bar in 1825 and began his law practice in Jefferson City, Missouri in 1828. He was appointed by Governor John G. Miller as Secretary of State in 1830, serving four years. In 1837, he was elected to the Missouri House of Representatives in 1836. Associating himself with Thomas Hart Benton, Edwards became involved in the monetary policy question. He opposed privately held banks and the production of small denomination bills. This political stand RECORDS OF GOVERNOR JOHN CUMMINS EDWARDS paid off as Edwards earned a position as a district judge in Cole County from 1832-1837. He also served as a justice on the Missouri Supreme Court from 1837-1839. -

Insurance Fraud Prosecutor How’D They Find Out? INSURANCE FRAUD IS a SERIOUS CRIME

N E W J E R S E Y INSURANCE FFrraudaud Special Report: Cracking Fraud Rings OIFP Draws International Praise Closing Loopholes: Proposals for Legislative and Regulatory Reform New Crime Takes Aim at Insurance Cheats How “Runners” Corrupt the Health Care System Public and Private Sectors Join Forces in Fraud War 2003 Annual Report of the New Jersey Office of the Insurance Fraud Prosecutor How’d they find out? INSURANCE FRAUD IS A SERIOUS CRIME. Don’t Do It. Don’t Tolerate It. Call Confidentially 1.877.55.FRAUD NEW JERSEY OFFICE OF INSURANCE FRAUD PROSECUTOR Inside Front Cover This page was intentionally left blank Annual Report of Annual Report Staff John J. Smith, Jr. First Assistant The New Jersey Insurance Fraud Prosecutor Assistant Attorney General Stephen D. Moore Office of the Editor Supervising Deputy Attorney General Melaine Campbell Co-Editor Insurance Fraud Supervising Deputy Attorney General Feature Writers John Butchko Prosecutor Special Assistant Norma R. Evans for Calendar Year 2003 Supervising Deputy Attorney General John Krayniak Supervising Deputy Attorney General Submitted Michael A. Monahan March 1, 2004 Supervising Deputy Attorney General (Pursuant to N.J.S.A. 17:33A-24d) Scott R. Patterson Supervising Deputy Attorney General Stephanie Stenzel Supervising State Investigator Contributors Jennifer Fradel Supervising Deputy Attorney General Peter C. Harvey Charles Janousek Attorney General Special Assistant Barry T. Riley Vaughn L. McKoy Supervising State Investigator Director, Division of Criminal Justice Photographers Vincent A. Matulewich Greta Gooden Brown Managing Deputy Chief Investigator Insurance Fraud Prosecutor Carlton A. Cooper Civil Investigator Production Paul Kraml Prepared by: Art Director Sina Adl Office of the Attorney General Graphic Designer Department of Law and Public Safety Division of Criminal Justice Administrative and Technical Support Office of the Insurance Fraud Prosecutor Paula Carter Susan Cedar P.O. -

"With the Help of God and a Few Marines,"

WITH THE HELP OF GOD NDAFEW ff R E3 ENSE PETIT P LAC I DAM SUB LIBE > < m From the Library of c RALPH EMERSON FORBES 1866-1937 o n > ;;.SACHUSETTS BOSTON LIBRARY "WITH THE HELP OF GOD AND A FEW ]\/[ARINES" "WITH THE HELP OF GOD AND A FEW MARINES" BY BRIGADIER GENERAL A. W. CATLIN, U. S. M. C. WITH THE COLLABORATION OF WALTER A. DYER AUTHOR OF "HERROT, DOG OF BELGIUM," ETC ILLUSTRATED Gaeden City New York DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY 1919 » m Copyright, 1918, 1919, by DOUBLEDAY, PaGE & COMPANY All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages including the Scandinavian UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS - LIBRARY { AT BOSTON CONTENTS PAGE ix Introduction , , . PART I ' MARINES TO THE FRONT I CHAPTER I. What Is A Marine? 3 II. To France! ^5 III. In the Trenches 29 IV. Over the Top 44 V. The Drive That Menaced Paris 61 PART II fighting to save PARIS VI. Going In 79 VIL Carrying On 9i VIII. "Give 'Em Hell, Boys!" 106 IX. In Belleau Wood and Bouresches 123 X. Pushing Through ^3^ XI. "They Fought Like Fiends'* ........ 161 XII. "Le Bois de LA Brigade de Marine" 171 XIII. At Soissons and After 183 PART III soldiers of the sea XIV. The Story of the Marine Corps 237 XV. Vera Cruz AND THE Outbreak of War 251 XVI. The Making of a Marine 267 XVII. Some Reflections on the War 293 APPENDIX I. Historical Sketch 3^9 II. The Marines' Hymn .323 III. Major Evans's Letter 324 IV. Cited for Valour in Action 34^ LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS HALF-TONE Belleau Wood . -

ARTS Fall and Winter 2018 G

A dining experience that goes beyond what’s on your plate. Celebrate our nation’s founding farmers & explore the exclusive artwork at Founding Farmers King of Prussia. To learn more & reserve your table, visit FoundingFarmers.com. TOURS PUBLIC PROGRAMING SPECIAL EVENTS PRIVATE RENTALS WWW.BAHISTORICDISTRICT.ORG ~ 215.947.2004 2 3 DISCOVER THE ARTS A LETTER from OUR PRESIDENT 6 18 Comedy Preview Historic Holiday Tours elcome to Valley Forge & Montgomery County, a land of timeless beauty Act II Playhouse, Keswick Theatre, and Celebrate the Season at Montgomery Valley Forge Casino Resort County’s Historic Attractions where the arts come alive, history marches off the page, and memories W are made. This guide is designed to help you discover an amazing arts destination perfect for your next weekend getaway or staycation. 8 20 Arts on Campus Discover Montco’s MONTCO IS HOME TO MORE THAN Manor College, Montgomery County House of Peace Mike Bowman, President & CEO Community College, and Ursinus College Visit the One and Only Synagogue Designed 200 ARTS ATTRACTIONS by the Legendary Frank Lloyd Wright In these pages you’ll read about: 10 Ardmore Music Hall 22 • Live music venues, like Ardmore Music Hall, which has hosted acts ranging Puts Montco Music Scene Artistic Places to from George Clinton & P-Funk to The Hooters, Snarky Puppy, and Macy Gray. The on the Map Tie the Knot venue celebrated its five-year anniversary this September. Montgomery County Concert Venue Six Scenic Spots to Plan Your Celebrates Five Year Anniversary Wedding Weekend • A 2018/2019 season preview of live theater and comedy acts at Montco’s award-winning playhouses. -

Montgomery County, the Second Hundred Years

C H A P T E R 3 3 NARBERTH 1980 Area: 0.52 square mile ESTABLISHED: 1895 The Narberth Association in 1891 installed sixty oil lamps on the Narberth Park tract of developer S. Almira Vance at the residents’ expense. It fur nished oil, and a lamplighter earned $7.50 a month. By spring of 1893, the Bala and Merion Electric Com pany had installed electric street lighting on the tract, featuring twenty-four lights of sixteen candlepower Before becoming a borough in 1895, Narberth was each. Narberth Park still had just forty-five houses, not one village but six successive settlements—Indian, and Narberth Avenue was the only macadamized Swedish, Welsh, the hamlet of Libertyville, the street. Pavements were of wood. There were no con nucleus of a “Godey’s L ady’s Book town” called necting drains or sewer system, and no police. Elm, and three simultaneous tract-house develop Local residents no longer had to depend on the post ments: Narberth Park, the south-side tract, and office at General Wayne Inn. Another, to be called Belmar. Narberth Park Association, called after the Elm, had been sought and denied because of a name tract development of that name and begun by fifteen conflict with an existing facility. However, in 1886 a of its residents, originated on October 9, 1889. This Narberth post office was approved. It was located in organization seemingly started just to provide simple the railroad station, which itself underwent a name community services on the north side of Elm Station change from Elm to Narberth in 1892. -

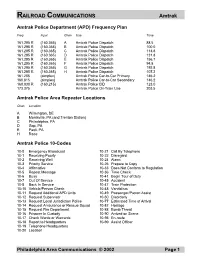

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 88.5 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA (and Trenton Station) C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department -

Transportation Planning for the Philadelphia–Harrisburg “Keystone” Railroad Corridor

VOLUME I Executive Summary and Main Report Technical Monograph: Transportation Planning for the Philadelphia–Harrisburg “Keystone” Railroad Corridor Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation March 2004 Disclaimer: This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation solely in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents or use thereof, nor does it express any opinion whatsoever on the merit or desirability of the project(s) described herein. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Any trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the object of this report. Note: In an effort to better inform the public, this document contains references to a number of Internet web sites. Web site locations change rapidly and, while every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of these references, they may prove to be invalid in the future. Should an FRA document prove difficult to find, readers should access the FRA web site (www.fra.dot.gov) and search by the document’s title or subject. 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FRA/RDV-04/05.I 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Technical Monograph: Transportation Planning for the March 2004 Philadelphia–Harrisburg “Keystone” Railroad 6. Performing Organization Code Corridor⎯Volume I: Executive Summary and Main Report 7. Authors: 8. Performing Organization Report No. For the engineering contractor: Michael C. Holowaty, Project Manager For the sponsoring agency: Richard U. Cogswell and Neil E. Moyer 9. -

Fellow Logisticians, on Behalf of Your Logistics Officer Association, Welcome to Washington DC and the 2012 LOA National Symposi

Fellow Logisticians, On behalf of your Logistics Officer Association, welcome to Washington DC and the 2012 LOA National Symposium! The event team has done a great job recognizing three decades of impact with the theme “30 Years of Developing Logisticians,” and I know we will all benefit from the presentations, exchanges, and discussions. This year’s agenda and slate of speakers is sure to inform and stimulate ideas on how logisticians can further enhance our important part of National Defense. Something new this year is the Professional Development Day—a training day that will further arm you with tools of our discipline. I encourage you to maximize this opportunity by learning something outside of your day-to-day functional area or increase your expertise in a specific skill—but in both cases, helping to facilitate related discussions about the issues we currently face. The speaker line-up is crafted to highlight the necessity of deliberately developing logisticians, and why that makes a difference in the way Air Force logistics supports combatant commanders across the globe. From breakout panels to main stage, you will hear how we are adapting professional development to align with urgent and future Air Force requirements. As a service— and as part of the joint force—we will continue to focus on enabling all logisticians to meet the readiness needs of fellow Airmen and commanders in the most efficient way. We’ll also continue to rely on LOA to further that focus through dynamic chapter events, thought- provoking member articles in the Exceptional Release, and of course, this capstone symposium that brings senior Air Force leadership and loggies together. -

4Th Div. Winsunit

FUTURE DECISIVE There la still deci- ■ Leyte is the dirty fight ahead sive battle for our for Leyte, News- homeland. Gen. man Geo. —Folster. Yamashlta.— MARINECORPSCHEVRON PUBLISHED BY TH£ UniTtD STOTtt mflßints in thu sun diego aka Vol. Ih, No. 46 Saturday Morning-, November 18, 1944 1 3500 Leatherneck Vets 4th Div. Wins Unit Citation Members of the 4th Mar. Div. entire length of the island, press-- and various attached units have ing on against bitter opposition OfPeleliu Dock In S. D. been awarded the Presidential Unit for 25 days to crush all resistance Early Christmas action. at Cape Glou- tlal airs, amid cheers and shrill Citation for "outstanding perform- in the zone of Victors Peleliu, brief rest and Guadalcanal, 3551 mem- whistling of those aboard. ance in combat during the seizure "With but a period In Packages Stump cester which to reorganize and of Ist Mar. Div, veterans The men were greeted at the of the islands of Saipan and re-equip, bers the the division hurled its full fighting months of overseas service, dock by a group of WRs who Tinian," it was announced In at SO against the Overseas Marines back home yesterday. waved them ashore and then Washington this week. power dangerously nar- arrived row beaches of Tinian on July 24 SOMEWHERE IN THE PA- the big ship on which they passed out cigarets—a rare com- The citation reads: Marines of As and expanded the beach- CIFIC (Delayed) a *iffl»#e the crossing was nosed into modity these days and candy rapidly — l "For outstanding performance In continued field artillery unit preparing for Marine bands alter- bars. -

The Haverford Journal Volume 4, Issue 1

2008-2009 (VOL. 4, ISSUE 1) 1 The Haverford Journal Volume 4, Issue 1 Published by the Haverford Journal Editorial Board MANAGING EDITORS Stephen Chehi ‘11 Thea Hogarth ‘11 PRODUCTION Thea Hogarth ‘11 BOARD MEMBERS Daniel Arnstein ‘09 COVER DESIGN Nicholas Lotito ‘10 Candice Smith ‘11 Candice Smith ‘11 Sarah Walker ‘08 FACULTY ADVISOR Sam Kaplan ‘10 Phil Bean Associate Dean of the College 2 THE HAVERFORD JOURNAL 2008-2009 (VOL. 4, ISSUE 1) 3 Dear Haverford, Welcome to the next generation of the Haverford Journal! Haverford Journal 2.0, if you will. If you’re familiar with this little publication, you have probably already noticed a lot of the superficial changes; if this is your first time reading the Journal, trust us, this cover is much cooler than the old one. So, why are we writing to you? Other than to point out the obvious, we, Thea Hoga- rth and Steve Chehi, wanted to fill you in on what we’ve been up to for the past semester. The Journal is a relatively young publication, which really means that every time the old editors graduate, the new editors try to do something new. With no real precedent to guide us (not even the phone number of a printing company), we’ve decided to preserve what the original editors started, but change our attitudes just a little bit. We won’t bore you with all the details, but we’d like to point out just a few of the new features to be excited about. First, you’ll notice the subtitle on the cover, “Myth & Marginality;” from now on we hope to title our issues according to a theme that unites all the papers we select.