Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

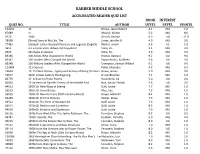

Barber Middle School Accelerated Reader Quiz List Book Interest Quiz No

BARBER MIDDLE SCHOOL ACCELERATED READER QUIZ LIST BOOK INTEREST QUIZ NO. TITLE AUTHOR LEVEL LEVEL POINTS 124151 13 Brown, Jason Robert 4.1 MG 5.0 87689 47 Mosley, Walter 5.3 MG 8.0 5976 1984 Orwell, George 8.9 UG 17.0 78958 (Short) Story of My Life, The Jones, Jennifer B. 4.0 MG 3.0 77482 ¡Béisbol! Latino Baseball Pioneers and Legends (English) Winter, Jonah 5.6 LG 1.0 9611 ¡Lo encontramos debajo del fregadero! Stine, R.L. 3.1 MG 2.0 9625 ¡No bajes al sótano! Stine, R.L. 3.9 MG 3.0 69346 100 Artists Who Changed the World Krystal, Barbara 9.7 UG 9.0 69347 100 Leaders Who Changed the World Paparchontis, Kathleen 9.8 UG 9.0 69348 100 Military Leaders Who Changed the World Crompton, Samuel Willard 9.1 UG 9.0 122464 121 Express Polak, Monique 4.2 MG 2.0 74604 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and Ecstasy of Being Thirteen Howe, James 5.0 MG 9.0 53617 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Grace/Bruchac 7.1 MG 1.0 66779 17: A Novel in Prose Poems Rosenberg, Liz 5.0 UG 4.0 80002 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East Nye, Naomi Shihab 5.8 UG 2.0 44511 1900-10: New Ways of Seeing Gaff, Jackie 7.7 MG 1.0 53513 1900-20: Linen & Lace Mee, Sue 7.3 MG 1.0 56505 1900-20: New Horizons (20th Century-Music) Hayes, Malcolm 8.4 MG 1.0 62439 1900-20: Print to Pictures Parker, Steve 7.3 MG 1.0 44512 1910-20: The Birth of Abstract Art Gaff, Jackie 7.6 MG 1.0 44513 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 8.3 MG 1.0 44514 1940-60: Emotion and Expression Gaff, Jackie 7.9 MG 1.0 36116 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 8.3 -

GENESIS: Lesson 8 - “This Will Make Us Famous”

GENESIS: Lesson 8 - “This Will Make Us Famous” Genesis 10:1, 8-10 (NLT), “This is the account of the families of Shem, Ham, and Japheth, the three sons of Noah. Many children were born to them after the great flood… 8 C ush was also the ancestor of Nimrod, who was the first heroic warrior on earth. 9 S ince he was the greatest hunter in the world, his name became proverbial. People would say, “This man is like Nimrod, the greatest hunter in the world.” 10 H e built his kingdom in the land of Babylonia, with the cities of Babylon, Erech, Akkad, and Calneh.” →Nimrod’s pride leads him to build a city that would become Babylon, which is a type or picture in the Bible of human pride in rebellion against God. This idea finds its fullest description in the Book of Revelation, as God pronounces His final judgment on the pride and wickedness of mankind in the last days: Revelation 17:1-6 (NLT), “One of the seven angels who had poured out the seven bowls came over and spoke to me. “Come with me,” he said, “and I will show you the judgment that is going to come on the great prostitute, who rules over many waters. 2 T he kings of the world have committed adultery with her, and the people who belong to this world have been made drunk by the wine of her immorality.” So, the angel took me in the Spirit= into the wilderness. There I saw a woman sitting on a scarlet beast that had seven heads and ten horns, and blasphemies against God were written all over it. -

The Bible in Music

The Bible in Music 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb i 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM The Bible in Music A Dictionary of Songs, Works, and More Siobhán Dowling Long John F. A. Sawyer ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiiiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by Siobhán Dowling Long and John F. A. Sawyer All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dowling Long, Siobhán. The Bible in music : a dictionary of songs, works, and more / Siobhán Dowling Long, John F. A. Sawyer. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-8451-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-8452-6 (ebook) 1. Bible in music—Dictionaries. 2. Bible—Songs and music–Dictionaries. I. Sawyer, John F. A. II. Title. ML102.C5L66 2015 781.5'9–dc23 2015012867 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

Survival and Postcolonialism in Timothy Findley's Not Wanted On

Survival and Postcolonialism in Timothy Findley’s Not Wanted on the Voyage Riikka Antikainen University of Tampere School of Language, Translation and Literary Studies English Philology Pro Gradu Thesis May 2013 Tampereen yliopisto Englantilainen filologia Kieli-, käännös- ja kirjallisuustieteiden yksikkö ANTIKAINEN, RIIKKA: Survival and Postcolonialism in Timothy Findley’s Not Wanted on the Voyage Pro Gradu -tutkielma, 68 sivua Toukokuu 2013 Tarkastelen tutkimuksessani postkolonialismia ja selviytymistä Timothy Findleyn romaanissa Not Wanted on the Voyage (1984). Kyseistä romaania on tutkittu verraten vähän, vaikka eri tutkijat ovat päätyneet mitä erilaisimpiin tulkintoihin sen merkityksistä. Itse käsittelen sitä kanadalaisena, postkolonialistisena romaanina, jonka tärkeimmäksi teemaksi nousee selviytyminen. Lähtökohta tälle tulkinnalle on Margaret Atwoodin kirja Survival , josta on mahdollista löytää paljon yhtymiskohtia Findleyn romaaniin ja jonka sidon postkolonialistiseen käsitykseen itsestä ja toisesta. Keskeisimmät tutkimuskysymykseni ovat miksi selviytyä, miten selviytyä ja mitä tapahtuu selviytymisen jälkeen. Näiden kysymysten pohjalta pohdin tarinaa myös kolonialistisen ja postkolonialistisen ajan allegoriana. Keskityn tutkimuksessani ensin henkilöihin ja olosuhteisiin, jotka luovat uhreja ja pakottavat selviytymään, minkä jälkeen käsittelen yksittäisiä hahmoja erilaisina uhreina. Lopuksi pohdin selviytymistä ajan ja maailman, tai yhteiskunnan, kannalta pyrkien sitomaan Findleyn romaanin laajempaan, postkolonialistiseen viitekehykseen. -

D'ei Chochmah L'nafshechah

Erev Shabbos Kodesh Parshas Noach 5770 D’ei Chochmah L’nafshechah “Let your soul know wisdom” Parshas Noach From the discourses of Moreinu v’Rabeinu the Gaon and Tzaddik Shlit”a - not for general circulation - Published by the Yam Hachochmah Institute Under the auspices of “Yeshivas Toras Chochom” for the study of the revealed and hidden Torah D’ei Chochmah L’Nafshechah Parshas Noach Shalosh Seudos 1 of Parshas Noach 5768 " ֵאֶלּה תּוֹ ְלדֹת נַֹח נַֹח ִאישׁ ַצִדּיק ָתִּמים ָהָיה ְבּדֹרָֹתיו ֶאת- ָהֱאלֹקים ִהְתַהֶלּ ְ ך- נֹ ַ ח. ַויּוֶֹלד נַֹח ְשׁלָֹשׁה ָבִנים ֶאת- ֵשׁם ֶאת - ָחם ְוֶאת - ָיֶפת ." “These are the chronicles of Noach: Noah was a righteous man, faultless in his generation. Noach walked with Hashem. Noach fathered three sons: Shem, Cham, and Yafes.” 2 Rashi explains [that the verse begins by mentioning Noach’s offspring and concludes with his praise 3] because the verse’s mention of Noach is a The“—”ֵזֶכר ַצִדּיק , ִלְבָרָכה “ ,recounting of his his praise. As we find in the verse mention [or memory] of a tzaddik is a blessing.”4 Or this is to teach that the main progeny of the righteous is their good deeds. The Three Sons of Noach The Zohar teaches that the three children of Noach have divergent spiritual sources. The source of Shem is the right side, Cham is sourced in the left and Yafes is sourced in the middle path, which is a blend of both right and 1 This lesson was delivered at the third meal of Shabbos. 2 Bereishis 6:9-10 3 Gur Aryeh , ad loc. -

Hazard from Himalayan Glacier Lake Outburst Floods

Hazard from Himalayan glacier lake outburst floods Georg Veha,1, Oliver Korupa,b, and Ariane Walza aInstitute of Environmental Science and Geography, University of Potsdam, 14476 Potsdam-Golm, Germany; and bInstitute of Geosciences, University of Potsdam, 14476 Potsdam-Golm, Germany Edited by Andrea Rinaldo, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, and approved November 27, 2019 (received for review August 27, 2019) Sustained glacier melt in the Himalayas has gradually spawned (17). While the distribution and dynamics of moraine-dammed more than 5,000 glacier lakes that are dammed by potentially lakes have been mapped extensively in recent years (12, 18–21), unstable moraines. When such dams break, glacier lake outburst objectively appraising the current Himalayan GLOF hazard has floods (GLOFs) can cause catastrophic societal and geomorphic remained challenging. The high-alpine conditions limit detailed impacts. We present a robust probabilistic estimate of average fieldwork, leading researchers to extract proxies of hazard from GLOFs return periods in the Himalayan region, drawing on 5.4 increasingly detailed digital topographic data and satellite imagery. billion simulations. We find that the 100-y outburst flood has These data allow for readily measuring or estimating the geometry of +3.7 6 3 an average volume of 33.5 /−3.7 × 10 m (posterior mean and ice and moraine dams, the possibility of avalanches or landslides 95% highest density interval [HDI]) with a peak discharge of entering a lake, or the water volumes released by outbursts (9, 18, 20). +2,000 3 −1 15,600 /−1,800 m ·s . Our estimated GLOF hazard is tied to Ranking these diagnostics in GLOF hazard appraisals has mostly the rate of historic lake outbursts and the number of present lakes, relied on expert judgment (18, 22), because triggers and condi- which both are highest in the Eastern Himalayas. -

Gaps and Challenges of Flood Risk Management in West African

Gaps and challenges of flood risk management in West African coastal cities Ouikotan, R.Ba, van der Kwast, J.a, Mynett, Aa , Afouda, Ab a UNESCO-IHE, Water Science and Engineering Department P.O.Box 3015, 2601 DA , DelFt, THe NetHerlands b University oF Abomey-Calavi, Applied Hydrology Laboratory, 01BP452, Benin Abstract West African coastal cities have been struck by repeated flooding leading to huge damage and loss of lives. This testifies that the measures are not efficient. This paper tries to point out the gaps and challenges for an adequate flood risk management (FRM). Four cities were selected as case studies. In general, adequate data and assessment tools do not exist due to lack of fund and skilled personnel. FRM projects are isolated and measures are not well maintained. FRM should be handled in a holistic manner taking into account all possible flood types and climate and demographic changes scenarios. Keywords: flood risk management strategies, West African coastal cities, climate change, urban growth 1. Introduction Flood in West Africa is a growing issue. According to the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, the number of disaster flood events has evolved during the past four decades from 4 to 19, 42 and 105. Accordingly, the number of fatalities also, evolved from 0 to 252, 586 and 1155 respectively. From 2010 to 2015, 57 disastrous flood events were already recorded with 1169 fatalities. The present trend of flood frequency and the huge magnitude of the damage induced testify that flood management measures implemented are not adequate and efficient. At a global level, flood management has evolved from flood control approach to flood risk management. -

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah's Flood and Plate Tectonics

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah’s Flood and Plate Tectonics by Steven Ball, Ph.D. September 2003 Dedication I dedicate this work to my friend and colleague Rodric White-Stevens, who delighted in discussing with me the geologic wonders of the Earth and their relevance to Biblical faith. Cover picture courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, copyright free 1 Introduction It seems that no subject stirs the passions of those intending to defend biblical truth more than Noah’s Flood. It is perhaps the one biblical account that appears to conflict with modern science more than any other. Many aspiring Christian apologists have chosen to use this account as a litmus test of whether one accepts the Bible or modern science as true. Before we examine this together, let me clarify that I accept the account of Noah’s Flood as completely true, just as I do the entirety of the Bible. The Bible demonstrates itself to be reliable and remarkably consistent, having numerous interesting participants in various stories through which is interwoven a continuous theme of God’s plan for man’s redemption. Noah’s Flood is one of those stories, revealing to us both God’s judgment of sin and God’s over-riding grace and mercy. It remains a timeless account, for it has much to teach us about a God who never changes. It is one of the most popular Bible stories for children, and the truth be known, for us adults as well. It is rather unfortunate that many dismiss the account as mythical, simply because it seems to be at odds with a scientific view of the earth. -

1. His:First Novel, the Great Weaver of Kashmir, Marked His Remmciation Of

Technophobia 4: Occidental College Tossups 4117/04 3:51 PM Technophobia 4: Massive Quizbowl Overdose Tossups by Occidental College (Wesley Mathews) and M. Swiatek 1. His:first novel, The Great Weaver ofKashmir, marked his remmciation ofhis Catholic faith and demonstrated his growing appetite for Socialism. Independent People, The Light of the World, and Salka Valka reflect utopian ideals, while his later novels, such as Paradise Reclaimed and The Fish Can Sing discuss philosophical issues. For 10 points--name this controversial author of Iceland's Bell, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1955. answer: Halldor Laxness or Halldor Kiljan Gudjonsson 2. Falls such as the Aughrabies Falls make this river unnavigable, and the Bogoeberg Dam prevents its enormous amounts of silt from clogging reservoirs and hindering irrigation. Rising in the Maluti Mountains, it flows northwest, then west, forming the boundary of the Orange Free State and Cape Province and part ofNamibia's southern border before emptying into the Atlantic Ocean. For 10 points--name this South African River which was named for a Dutch ruling house, not a colour. answer: Orange River 3. A hostage of the sultan Murad II, this Prince of Emathia was given the rank of bey and a name after Alexander the Great. A Vivaldi opera and ballads by Ronsard and Longfellow tell of his humane war tactics, which earned him the title "Athlete of Christendom," during the thirteen times he repulsed the Ottoman Turks who attempted to overrun his nation. For 10 points--name this man honoured by a statue in his namesake square in Tirana, the national hero of Albania. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Wednesday, March 18, 2009 2:36:33PM School: Churchland Academy Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 9318 EN Ice Is...Whee! Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 9340 EN Snow Joe Greene, Carol LG 0.3 0.5 59 F 36573 EN Big Egg Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 99 F 9306 EN Bugs! McKissack, Patricia C. LG 0.4 0.5 69 F 86010 EN Cat Traps Coxe, Molly LG 0.4 0.5 95 F 9329 EN Oh No, Otis! Frankel, Julie LG 0.4 0.5 97 F 9333 EN Pet for Pat, A Snow, Pegeen LG 0.4 0.5 71 F 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 55 F 9336 EN Rain! Rain! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 63 F 9338 EN Shine, Sun! Greene, Carol LG 0.4 0.5 66 F 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 171 F 9305 EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Stevens, Philippa LG 0.5 0.5 100 F 7255 EN Can You Play? Ziefert, Harriet LG 0.5 0.5 144 F 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol LG 0.5 0.5 58 F 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret LG 0.5 0.5 196 F 7282 EN Lucky Bear Phillips, Joan LG 0.5 0.5 150 F 31542 EN Mine's the Best Bonsall, Crosby LG 0.5 0.5 106 F 901618 EN Night Watch (SF Edition) Fear, Sharon LG 0.5 0.5 51 F 9349 EN Whisper Is Quiet, A Lunn, Carolyn LG 0.5 0.5 63 NF 74854 EN Cooking with the Cat Worth, Bonnie LG 0.6 0.5 135 F 42150 EN Don't Cut My Hair! Wilhelm, Hans LG 0.6 0.5 74 F 9018 EN Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. -

Einstein, History, and Other Passions : the Rebellion Against Science at the End of the Twentieth Century

Einstein, history, and other passions : the rebellion against science at the end of the twentieth century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Holton, Gerald James. 2000. Einstein, history, and other passions : the rebellion against science at the end of the twentieth century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Published Version http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674004337 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:23975375 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA EINSTEIN, HISTORY, ANDOTHER PASSIONS ;/S*6 ? ? / ? L EINSTEIN, HISTORY, ANDOTHER PASSIONS E?3^ 0/" Cf72fM?y GERALD HOLTON A HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS C%772^r?<%gf, AizziMc^zzyeZZy LozzJozz, E?zg/%??J Q AOOO Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in capital letters. PHYSICS RESEARCH LIBRARY NOV 0 4 1008 Copyright @ 1996 by Gerald Holton All rights reserved HARVARD UNIVERSITY Printed in the United States of America An earlier version of this book was published by the American Institute of Physics Press in 1995. First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2000 o/ CoMgre.w C%t%/og;Hg-zM-PMMt'%tz'c7t Dzztzz Holton, Gerald James. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour.