Scott-Wyatt-Interview-Transcript1-Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpretação Em Tempo Real Sobre Material Sonoro Pré-Gravado

Interpretação em tempo real sobre material sonoro pré-gravado JOÃO PEDRO MARTINS MEALHA DOS SANTOS Mestrado em Multimédia da Universidade do Porto Dissertação realizada sob a orientação do Professor José Alberto Gomes da Universidade Católica Portuguesa - Escola das Artes Julho de 2014 2 Agradecimentos Em primeiro lugar quero agradecer aos meus pais, por todo o apoio e ajuda desde sempre. Ao orientador José Alberto Gomes, um agradecimento muito especial por toda a paciência e ajuda prestada nesta dissertação. Pelo apoio, incentivo, e ajuda à Sara Esteves, Inês Santos, Manuel Molarinho, Carlos Casaleiro, Luís Salgado e todos os outros amigos que apesar de se encontraram fisicamente ausentes, estão sempre presentes. A todos, muito obrigado! 3 Resumo Esta dissertação tem como foco principal a abordagem à interpretação em tempo real sobre material sonoro pré-gravado, num contexto performativo. Neste caso particular, material sonoro é entendido como música, que consiste numa pulsação regular e definida. O objetivo desta investigação é compreender os diferentes modelos de organização referentes a esse material e, consequentemente, apresentar uma solução em forma de uma aplicação orientada para a performance ao vivo intitulada Reap. Importa referir que o material sonoro utilizado no software aqui apresentado é composto por músicas inteiras, em oposição às pequenas amostras (samples) recorrentes em muitas aplicações já existentes. No desenvolvimento da aplicação foi adotada a análise estatística de descritores aplicada ao material sonoro pré-gravado, de maneira a retirar segmentos que permitem uma nova reorganização da informação sequencial originalmente contida numa música. Através da utilização de controladores de matriz com feedback visual, o arranjo e distribuição destes segmentos são alterados e reorganizados de forma mais simplificada. -

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131

Music 80C History and Literature of Electronic Music Tuesday/Thursday, 1-4PM Music Center 131 Instructor: Madison Heying Email: [email protected] Office Hours: By Appointment Course Description: This course is a survey of the history and literature of electronic music. In each class we will learn about a music-making technique, composer, aesthetic movement, and the associated repertoire. Tests and Quizzes: There will be one test for this course. Students will be tested on the required listening and materials covered in lectures. To be prepared students must spend time outside class listening to required listening, and should keep track of the content of the lectures to study. Assignments and Participation: A portion of each class will be spent learning the techniques of electronic and computer music-making. Your attendance and participation in this portion of the class is imperative, since you will not necessarily be tested on the material that you learn. However, participation in the assignments and workshops will help you on the test and will provide you with some of the skills and context for your final projects. Assignment 1: Listening Assignment (Due June 30th) Assignment 2: Field Recording (Due July 12th) Final Project: The final project is the most important aspect of this course. The following descriptions are intentionally open-ended so that you can pursue a project that is of interest to you; however, it is imperative that your project must be connected to the materials discussed in class. You must do a 10-20 minute in class presentation of your project. You must meet with me at least once to discuss your paper and submit a ½ page proposal for your project. -

Computer Music

THE OXFORD HANDBOOK OF COMPUTER MUSIC Edited by ROGER T. DEAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. First published as an Oxford University Press paperback ion Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Oxford handbook of computer music / edited by Roger T. Dean. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-979103-0 (alk. paper) i. Computer music—History and criticism. I. Dean, R. T. MI T 1.80.09 1009 i 1008046594 789.99 OXF tin Printed in the United Stares of America on acid-free paper CHAPTER 12 SENSOR-BASED MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS AND INTERACTIVE MUSIC ATAU TANAKA MUSICIANS, composers, and instrument builders have been fascinated by the expres- sive potential of electrical and electronic technologies since the advent of electricity itself. -

Talbertronic Festival Workshop I

◊◊ THE OBERLIN COLLEGE CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC PRESENTS ◊◊ Talbert ronic Festival March 2-4, 2017 Oberlin, Ohio Dear Friends, The writer Bill Bryson observed that “few things last for more than a generation in America.” Indeed, even in the slow-to-change world of academic institutions, it is often the case that non-traditional programs or departments come and go in a decade or two. And yet we gather this weekend in honor of John Talbert’s retirement to celebrate the sustained energy and success of the TIMARA Department as it approaches the 50th anniversary of its origins. Our longevity has a lot to do with our adaptability, and our adaptability over the past 38 years has a lot to do with John. Even as he walks out the door, John remains a step ahead, always on the lookout for new methods and technologies but also wise in his avoidance of superficial trends. Take a moment this weekend to consider the number and variety of original compositions, artworks, performances, installations, recordings, instrument designs, and other projects that John has influenced and help bring into being during his time at Oberlin. All the while, John has himself designed and built literally rooms full of unique and reliable devices that invite student and faculty artists to express themselves with sonic and visual media. Every bit of the teaching and learning that transpires each day in TIMARA is influenced by John and will continue to be for years to come. Even when he knows better (which by now is just about always), he is willing to trust his colleagues, humor us faculty and our outlandish requests, and let students make personal discoveries through experimentation. -

Sound-Source Recognition: a Theory and Computational Model

Sound-Source Recognition: A Theory and Computational Model by Keith Dana Martin B.S. (with distinction) Electrical Engineering (1993) Cornell University S.M. Electrical Engineering (1995) Massachusetts Institute of Technology Submitted to the department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1999 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1999. All Rights Reserved. Author .......................................................................................................................................... Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science May 17, 1999 Certified by .................................................................................................................................. Barry L. Vercoe Professor of Media Arts and Sciences Thesis Supervisor Accepted by ................................................................................................................................. Professor Arthur C. Smith Chair, Department Committee on Graduate Students _____________________________________________________________________________________ 2 Sound-source recognition: A theory and computational model by Keith Dana Martin Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on May 17, 1999, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering -

The Early History of Music Programming and Digital Synthesis, Session 20

Chapter 20. Meeting 20, Languages: The Early History of Music Programming and Digital Synthesis 20.1. Announcements • Music Technology Case Study Final Draft due Tuesday, 24 November 20.2. Quiz • 10 Minutes 20.3. The Early Computer: History • 1942 to 1946: Atanasoff-Berry Computer, the Colossus, the Harvard Mark I, and the Electrical Numerical Integrator And Calculator (ENIAC) • 1942: Atanasoff-Berry Computer 467 Courtesy of University Archives, Library, Iowa State University of Science and Technology. Used with permission. • 1946: ENIAC unveiled at University of Pennsylvania 468 Source: US Army • Diverse and incomplete computers © Wikimedia Foundation. License CC BY-SA. This content is excluded from our Creative Commons license. For more information, see http://ocw.mit.edu/fairuse. 20.4. The Early Computer: Interface • Punchcards • 1960s: card printed for Bell Labs, for the GE 600 469 Courtesy of Douglas W. Jones. Used with permission. • Fortran cards Courtesy of Douglas W. Jones. Used with permission. 20.5. The Jacquard Loom • 1801: Joseph Jacquard invents a way of storing and recalling loom operations 470 Photo courtesy of Douglas W. Jones at the University of Iowa. 471 Photo by George H. Williams, from Wikipedia (public domain). • Multiple cards could be strung together • Based on technologies of numerous inventors from the 1700s, including the automata of Jacques Vaucanson (Riskin 2003) 20.6. Computer Languages: Then and Now • Low-level languages are closer to machine representation; high-level languages are closer to human abstractions • Low Level • Machine code: direct binary instruction • Assembly: mnemonics to machine codes • High-Level: FORTRAN • 1954: John Backus at IBM design FORmula TRANslator System • 1958: Fortran II 472 • 1977: ANSI Fortran • High-Level: C • 1972: Dennis Ritchie at Bell Laboratories • Based on B • Very High-Level: Lisp, Perl, Python, Ruby • 1958: Lisp by John McCarthy • 1987: Perl by Larry Wall • 1990: Python by Guido van Rossum • 1995: Ruby by Yukihiro “Matz” Matsumoto 20.7. -

Subotnick-Lillevan 2015Edit.2016

Jan. 28, 2016 Washington, DC American University: Song and Dance Feb. 4, 2016 Brooklyn, NY Interpretations at Roulette: Song and Dance April 21, 2016 Copenhagen Jazzhouse: Song and Dance April 23, 2016 Malma, Sweden CTM Festival: Song and Dance May 21, 2016 Durham, NC Moogfest: Song and Dance May 27, 2016 Detroit Trip Metal Fest: Song and Dance Sept. 27, 2016 Brooklyn, NY After 9 Evenings, Issue Project Room: Song and Dance Nov. 1, 2016 London St. John Sessions: Song and Dance Nov. 4, 2016 Berlin Ableton Loop: Song and Dance Dec 27-29, 2016 Israel Colloquium & Performances Feb. 15, 2017 Philadelphia Annenberg Center (w/Lillevan) April 22, 2017 San Francisco Buchla Memorial Festival July 20-22, 2017 NYC Lincoln Center: Crowds and Power Morton Subotnick 2015 Other Events photo credit: Adam Kissick for RECORDINGS WERGO released in June 2015 After the Butterfly The Wild Beasts http://www.schott-music.com/news/archive/show,11777.html?newsCategoryId=19 Upcoming re-releases from vinyl on WERGO Fall 2015: Axolotl, Joel Krosnick, cello A Fluttering of Wings with the Juilliard Sting Quartet Ascent into Air from Double life of Amphibians The Last Dream of the Beat for soprano, Two Celli and Ghost electronics; Featuring Joan La Barbara, soprano Upcoming Mode Records: Complete Piano Music of Morton Subotnick The Other Piano, Liquid Strata, Falling Leaves and Three Piano Preludes. Featuring SooJin Anjou, pianist Release of a K-6 online music curriculum: Morton Subotnicks Music Academy https://musicfirst.com/msma 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PROGRAM INFO Pg 4 CONCERT LISTING AND BIOS Pg 5 CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pg 6 PRESS PHOTOS Pg 8 AUDIO AND VIDEO LINKS Pg 13 PRESS QUOTES Pg 15 TECH RIDER Pg 19 3 PROGRAM INFO Song and Dance PROGRAM DESCRIPTION A light and sound duet utilizing musical resources from my analog recordings combined with my most recent electronic patches and techniques performed spontaneously on my hybrid Buchla 200e/Ableton Live ’instrument’, with live video animation by Lillevan. -

THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION of the EARLY ELECTRONIC MUSIC SYNTHESIZER Author(S): Trevor Pinch and Frank Trocco Source: Icon, Vol

International Committee for the History of Technology (ICOHTEC) THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF THE EARLY ELECTRONIC MUSIC SYNTHESIZER Author(s): Trevor Pinch and Frank Trocco Source: Icon, Vol. 4 (1998), pp. 9-31 Published by: International Committee for the History of Technology (ICOHTEC) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23785956 Accessed: 27-01-2018 00:41 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms International Committee for the History of Technology (ICOHTEC) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Icon This content downloaded from 70.67.225.215 on Sat, 27 Jan 2018 00:41:54 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF THE EARLY ELECTRONIC MUSIC SYNTHESIZER Trevor Pinch and Frank Troceo In this paper we examine the sociological history of the Moog and Buchla music synthesizers. These electronic instruments were developed in the mid-1960s. We demonstrate how relevant social groups exerted influence on the configuration of synthesizer construction. In the beginning, the synthesizer was a piece of technology that could be designed in a variety of ways. Despite this interpretative flexibility in its design, it stabilised as a keyboard instrument. -

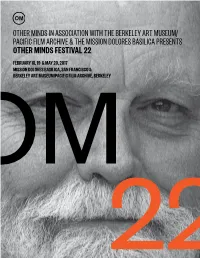

Other Minds in Association with the Berkeley Art

OTHER MINDS IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/ PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE & THE MISSION DOLORES BASILICA PRESENTS OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL 22 FEBRUARY 18, 19 & MAY 20, 2017 MISSION DOLORES BASILICA, SAN FRANCISCO & BERKELEY ART MUSEUM/PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE, BERKELEY 2 O WELCOME FESTIVAL TO OTHER MINDS 22 OF NEW MUSIC The 22nd Other Minds Festival is present- 4 Message from the Artistic Director ed by Other Minds in association with the 8 Lou Harrison Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive & the Mission Dolores Basilica 9 In the Composer’s Words 10 Isang Yun 11 Isang Yun on Composition 12 Concert 1 15 Featured Artists 23 Film Presentation 24 Concert 2 29 Featured Artists 35 Timeline of the Life of Lou Harrison 38 Other Minds Staff Bios 41 About the Festival 42 Festival Supporters: A Gathering of Other Minds 46 About Other Minds This booklet © 2017 Other Minds, All rights reserved 3 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR WELCOME TO A SPECIAL EDITION OF THE OTHER MINDS FESTIVAL— A TRIBUTE TO ONE OF THE MOST GIFTED AND INSPIRING FIGURES IN THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN CLASSICAL MUSIC, LOU HARRISON. This is Harrison’s centennial year—he was born May 14, 1917—and in addition to our own concerts of his music, we have launched a website detailing all the other Harrison fêtes scheduled in his hon- or. We’re pleased to say that there will be many opportunities to hear his music live this year, and you can find them all at otherminds.org/lou100/. Visit there also to find our curated compendium of Internet links to his work online, photographs, videos, films and recordings. -

Virtual Analog Buchla 259 Wavefolder

This is an electronic reprint of the original article. This reprint may differ from the original in pagination and typographic detail. Author(s): Fabián Esqueda, Henri Pöntynen, Vesa Välimäki, Julian D. Parker Title: Virtual analog Buchla 259 wavefolder Year: 2017 Version: Final published version Please cite the original version: Fabián Esqueda, Henri Pöntynen, Vesa Välimäki, Julian D. Parker. Virtual analog Buchla 259 wavefolder. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Digital Audio Effects (DAFx-17), Edinburgh, UK, pp. 192-199, September 2017. http://www.dafx.de/ Rights: © 2017 Authors. Reprinted with permission. This publication is included in the electronic version of the article dissertation: Esqueda, Fabián. Aliasing Reduction in Nonlinear Audio Signal Processing. Aalto University publication series DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS, 74/2018. All material supplied via Aaltodoc is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, and duplication or sale of all or part of any of the repository collections is not permitted, except that material may be duplicated by you for your research use or educational purposes in electronic or print form. You must obtain permission for any other use. Electronic or print copies may not be offered, whether for sale or otherwise to anyone who is not an authorised user. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Digital Audio Effects (DAFx-17), Edinburgh, UK, September 5–9, 2017 VIRTUAL ANALOG BUCHLA 259 WAVEFOLDER Fabián Esqueda, Henri Pöntynen, -

About Modular Synthesizers 12 Thoughts 18 Technical Details on Specific Modules 22 Principles / Events 32 Systems 38 Conclusion 43 List of References 44 Appendix 46

2 Table of Contents Abstract 5 Introduction 6 Research 8 Brief look into the history 10 About various real world principles in the history of music and art 10 About modular synthesizers 12 Thoughts 18 Technical details on specific modules 22 Principles / events 32 Systems 38 Conclusion 43 List of references 44 Appendix 46 3 4 Abstract English Basic research in translating biological, mechanical and chemical principles into electronic musical instrument language and vice versa. The subject of this diploma is exploration of all possible and impossible biological, mechanical and chemical events and their application in the field of electronic music. Electronic musical instruments can communicate between each other by standardized languages, either analog (CV) or digital (MIDI, OSC). In the first part of the research the translators from the real world events into the musical protocols and vice versa are produced. The second part of the research applies these technical solutions in the musical exploration of these real world principles. All of this is done in the open source fashion. Deutsch Die Grundlagenforschung zur Übersetzung biologischer, mechanischer und chemischer Grundlagen in die Sprache elektronischer Musikinstrumente und umgekehrt. Das Thema der Diplomarbeit ist die Untersuchung von allen möglichen und unmöglichen biologischen, mechanischen und chemischen Grundlagen und deren Anwendung im Bereich der elektronischen Musik. Elektronische Musikinstrumente können untereinander durch standardisierte Sprachen kommunizieren, entweder analog (CV) oder digital (MIDI, OSC). Im ersten Teil der Forschung werden Translatore von realen Welt-Prinzipien in musikalische Protokolle und umgekehrt produziert. Der zweite Teil der Forschung ist, diese technischen Lösungen in der musikalischen Erforschung dieser realen Welt-Prinzipien anzuwenden. -

A Narrative Exploring the Perception of Analog Synthesizer Enthusiasts' Identity and Communication Christoph Stefan Kresse Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2015 Synthesized: A Narrative Exploring the Perception of Analog Synthesizer Enthusiasts' Identity and Communication Christoph Stefan Kresse Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Kresse, Christoph Stefan, "Synthesized: A Narrative Exploring the Perception of Analog Synthesizer Enthusiasts' Identity and Communication" (2015). All Theses. 2114. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2114 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYNTHESIZED: A NARRATIVE EXPLORING THE PERCEPTION OF ANALOG SYNTHESIZER ENTHUSIASTS’ IDENTITY AND COMMUNICATION A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Communication, Technology, and Society by Christoph Stefan Kresse May 2015 Accepted by: Dr. Chenjerai Kumanyika, Ph.D., Committee Chair Dr. David Travers Scott, Ph.D. Dr. Darren L. Linvill, Ph.D. Dr. Bruce Whisler, Ph.D. i ABSTRACT This document is a written reflection of the production process of the creative project Synthesized, a scholarly-rooted documentary exploring the analog synthesizer world with focus on organizational structure and perception of social identity. After exploring how this production complements existing works on the synthesizer, electronic music, identity, communication and group association, this reflection explores my creative process and decision making as an artist and filmmaker through the lens of a qualitative researcher. As part of this, I will discuss logistic, as well as artistic and creative, challenges.