Client Satisfaction and Competency of Healthcare Providers with the Services of BRAC Maternity Centres – a Cross Sectional Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BANGLADESH Annual Human Rights Report 2016

BANGLADESH Annual Human Rights Report 2016 1 Cover designed by Odhikar with photos collected from various sources: Left side (from top to bottom): 1. The families of the disappeared at a human chain in front of the National Press Club on the occasion of the International Week of the Disappeared. Photo: Odhikar, 24 May 2016 2. Photo: The daily Jugantor, 1 April 2016, http://ejugantor.com/2016/04/01/index.php (page 18) 3. Protest rally organised at Dhaka University campus protesting the Indian High Commissioner’s visit to the University campus. Photo collected from a facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/SaveSundarbans.SaveBangladesh/videos/713990385405924/ 4. Police on 28 July fired teargas on protesters, who were heading towards the Prime Minister's Office, demanding cancellation of a proposed power plant project near the Sundarbans. Photo: The Daily Star, 29 July 2016, http://www.thedailystar.net/city/cops-attack-rampal-march-1261123 Right side (from top to bottom): 1. Activists of the Democratic Left Front try to break through a police barrier near the National Press Club while protesting the price hike of natural gas. http://epaper.thedailystar.net/index.php?opt=view&page=3&date=2016-12-30 2. Ballot boxes and torn up ballots at Narayanpasha Primary School polling station in Kanakdia of Patuakhali. Photo: Star/Banglar Chokh. http://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/5-killed-violence-1198312 3. On 28 July the National Committee to Protect, Oil, Gas, Natural Resources, Power and Ports marched in a protest rally towards the Prime Minister’s office. Photo: collected from facebook. -

Bangladesh Workplace Death Report 2020

Bangladesh Workplace Death Report 2020 Supported by Published by I Bangladesh Workplace Death Report 2020 Published by Safety and Rights Society 6/5A, Rang Srabonti, Sir Sayed Road (1st floor), Block-A Mohammadpur, Dhaka-1207 Bangladesh +88-02-9119903, +88-02-9119904 +880-1711-780017, +88-01974-666890 [email protected] safetyandrights.org Date of Publication April 2021 Copyright Safety and Rights Society ISBN: Printed by Chowdhury Printers and Supply 48/A/1 Badda Nagar, B.D.R Gate-1 Pilkhana, Dhaka-1205 II Foreword It is not new for SRS to publish this report, as it has been publishing this sort of report from 2009, but the new circumstances has arisen in 2020 when the COVID 19 attacked the country in March . Almost all the workplaces were shut about for 66 days from 26 March 2020. As a result, the number of workplace deaths is little bit low than previous year 2019, but not that much low as it is supposed to be. Every year Safety and Rights Society (SRS) is monitoring newspaper for collecting and preserving information on workplace accidents and the number of victims of those accidents and publish a report after conducting the yearly survey – this year report is the tenth in the series. SRS depends not only the newspapers as the source for information but it also accumulated some information from online media and through personal contact with workers representative organizations. This year 26 newspapers (15 national and 11 regional) were monitored and the present report includes information on workplace deaths (as well as injuries that took place in the same incident that resulted in the deaths) throughout 2020. -

Annex 13 Master Plan on Sswrd in Mymensingh District

ANNEX 13 MASTER PLAN ON SSWRD IN MYMENSINGH DISTRICT JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MINISTRY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT, RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND COOPERATIVES (MLGRD&C) LOCAL GOVERNMENT ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT (LGED) MASTER PLAN STUDY ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION THROUGH EFFECTIVE USE OF SURFACE WATER IN GREATER MYMENSINGH MASTER PLAN ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN MYMENSINGH DISTRICT NOVEMBER 2005 PACIFIC CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL (PCI), JAPAN JICA MASTER PLAN STUDY ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION THROUGH EFFECTIVE USE OF SURFACE WATER IN GREATER MYMENSINGH MASTER PLAN ON SMALL SCALE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT IN MYMENSINGH DISTRICT Map of Mymensingh District Chapter 1 Outline of the Master Plan Study 1.1 Background ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 1 1.2 Objectives and Scope of the Study ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 1 1.3 The Study Area ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 2 1.4 Counterparts of the Study ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 2 1.5 Survey and Workshops conducted in the Study ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 3 Chapter 2 Mymensingh District 2.1 General Conditions ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 4 2.2 Natural Conditions ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 4 2.3 Socio-economic Conditions ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 5 2.4 Agriculture in the District ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 5 2.5 Fisheries -

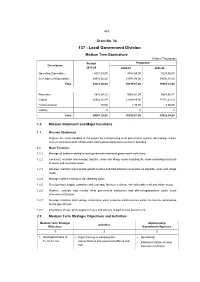

137 - Local Government Division

453 Grant No. 34 137 - Local Government Division Medium Term Expenditure (Taka in Thousands) Budget Projection Description 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 Operating Expenditure 4321,54,00 4753,69,00 5229,06,00 Development Expenditure 29919,66,00 31541,98,00 34696,18,00 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 Recurrent 7815,04,16 9003,87,04 8807,80,41 Capital 26425,35,84 27289,84,96 31115,37,59 Financial Asset 80,00 1,95,00 2,06,00 Liability 0 0 0 Total 34241,20,00 36295,67,00 39925,24,00 1.0 Mission Statement and Major Functions 1.1 Mission Statement Improve the living standard of the people by strengthening local government system, developing climate resilient rural and urban infrastructure and implementing socio-economic activities. 1.2 Major Functions 1.2.1 Manage all matters relating to local government and local government institutions; 1.2.2 Construct, maintain and manage Upazilla, union and village roads including the roads and bridges/culverts of towns and municipal areas; 1.2.3 Develop, maintain and manage growth centres and hats-bazaars connected via Upazilla, union and village roads; 1.2.4 Manage matters relating to safe drinking water; 1.2.5 Develop water supply, sanitation and sewerage facilities in climate risk vulnerable rural and urban areas; 1.2.6 Finance, evaluate and monitor local government institutions and offices/organizations under Local Government Division; 1.2.7 Develop, maintain and manage small-scale water resource infrastructures within the timeline determined by the government. 1.2.8 Enactment of Law, promulgation of rules and policies related to local government. -

Hazard Incidences in Bangladesh in March, 2016

Hazard Incidences in Bangladesh in March, 2016 Overview of Hazard Incidences in March 2016 Seven localised incidents occurred in March. Fire, Road Collapse, Bridge Platform Collapse, Wall Collapse and Chimney Collapse as well as two natural incidents, Nor’wester and Lightning were the major incidents stricken in this month. According to the dailies, Nor’wester struck on 6th, 7th and 20th March and affected 4 districts. Lightning occurred in on 22nd, 27th, 28th and 31st of this month. Also, there was Wall Collapse in Nawabganj upazila under Dinajpur district and Ishwarganj upazila of Mymensingh district. As well, a chimney of a rice mill collapsed on 5th March in Ambari upazila of Dinajpur district. In addition, a road collapsed at Gulshan in Dhaka and a bridge platform collapsed in Biswambhapur under Sunamganj district. Apart from these, 27 fire incidents occurred on 1st , 2nd, 9th, 10th, 11th, 14th, 16th,17th, 18th, 19th, 21st, 22nd, 24th and 26th March at Panchagarh, Nilphamari, Sylhet, Dinajpur, Thakurgaon, Manikganj, Pabna, Mymensingh, Joypurhat, Jhenaidah, Brahmanbaria, Dhaka, Gazipur, Natore, Netrokona, Barguna, Noakhali, Gopalganj, Madaripur, Gaibandha and Khulna districts, respectively. Description of the Events in March 2016 Nor’wester In March, Nor’wester hit 4 districts e.g. Dhaka, Rajbari, Chuadanga and Netrokona districts. Total 4 people were killed and 31 people injured including women and children (Table 1). On 7th March, ferry service at Goalandaghat paused for 12 hours during the storm. Nor’wester also caused damage to -

Reproductive Characteristics and Nutritional Status of Coastal Women

Chattagram Maa-O-Shishu Hospital Medical College Journal Volume 14, Issue 1, January 2015 Original Article Reproductive Characteristics and Nutritional Status of Coastal Women Nuruzzaman1* Abstract Md Ashraful Alam2 Women are more vulnerable in health and family planning and this vulnerability is Md Parvez Iqbal Sharif3 more in–depth in coastal area. The study was done to determine the reproductive Parveen Akter4 characteristics and nutritional status of women in coastal area. It was conducted in Nabeela Mazid5 Moheshkhali upazila of Cox’s Bazar district in 2013 among 220 purposively selected Shah Niaz Md Rubaid Anwar6 coastal women of reproductive age. Face to face interview was done through pre- tested questionnaire. Average age of the respondents was 26.5 years. Almost 60% of 1Nandail Upazila Health Complex them were Muslims and 44% were illiterate. The average monthly family income Mymansing, Bangladesh. and family size was Tk-6968.18 and 5.8 respectively. More than half (56%) of the respondents had history of regular use of contraceptives and oral pill was the most 2Department of Maternal and Child Health common type of contraceptive. Average number of children was 2.95. More than half National Institute of Preventive and Social Medicine (NIPSOM) Dhaka, Bangladesh. of them (54%) had history of home delivery. More than one-third (34%) of them were under nourished. Nutritional status was significantly associated with income 3Department of Community Medicine (p<0.05). Majority of them got early marriage (70%) but early marriage was not Chattagram Maa-O-Shishu Hospital Medical College significantly associated with their nutritional status. Age at first pregnancy and parity Chittagong, Bangladesh. -

Odhikar Annual Human Rights Report 2013

1 Introduction | : Odhikar Annual Human Rights Report 2013 Cover designed by Odhikar with photos collected from various sources: Clockwise from left: 1. Collapsed ruins of the Rana Plaza building –photo taken by Odhikar, 24/04/2013 2. Bodies of workers recovered from Rana Plaza –photo taken by Odhikar, 24/04/2013 3. Mohammad Nur Islam and Muktar Dai, who were shot dead by BSF at Bojrak border in Horipur Police Station, Thakurgaon District – photo taken by Odhikar, 03/01/2013 4. Photo Collage: Rizvi Hassan, victim of enforced disappearance from Chittagong; Mohammad Fakhrul Islam, victim of enforced disappearance from Middle Badda, Dhaka; Abdullah Umar Al Shahadat, victim of enforced disappearance from Mirpur, Dhaka; Humayun Kabir and Mohammad Saiful Islam, victims of enforced disappearance from Laksam, Comilla; Mohammad Tayob Pramanik, Kamal Hossain Patowari and Ibrahim Khalil, victims of enforced disappearance from Boraigram, Natore. All photographs collected from their families by Odhikar during the course of fact finding missions. 5. A broken idol of the Hindu goddess Kali at Rajganj under Begumganj Upazila in Noakhali District – photo taken by Odhikar, 03/03/2013 6. Bodies of Hefazate Islam activists at Dhaka Medical College Hospital Morgue – Photo collected from the daily Jugantor, 07/05/2013 2 Introduction | : Odhikar Annual Human Rights Report 2013 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................8 Human Rights and the Struggle for -

List of Upazilas of Bangladesh

List Of Upazilas of Bangladesh : Division District Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Akkelpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Joypurhat Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Kalai Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Khetlal Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Panchbibi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Adamdighi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Bogra Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Dhunat Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Dhupchanchia Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Gabtali Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Kahaloo Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Nandigram Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sariakandi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Shajahanpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sherpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Shibganj Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sonatola Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Atrai Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Badalgachhi Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Manda Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Dhamoirhat Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Mohadevpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Naogaon Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Niamatpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Patnitala Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Porsha Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Raninagar Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Sapahar Upazila Rajshahi Division Natore District Bagatipara -

Annex to Chapter 3. Results Framework for the 4Th HPBSP 2016

Annex to Chapter 3. Results Framework for the 4th HPBSP 2016-2021 Means of Result Indicator verification & Baseline & source Target 2021 timing Goal GI 1. Under-5 Mortality Rate (U5MR) BDHS, every 3 years 46, BDHS 2014 37 All citizens of GI 2. Neonatal Mortality Rate (NNMR) BDHS, every 3 years 28, BDHS 2014 21 Bangladesh enjoy health and well-being GI 3. Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) BMMS; MPDR 176, WHO 2015(http:// 105 www.who.int/ reproductivehealth/ publications/monitoring/ maternal-mortality-2015/ en/ GI 4. Total Fertility Rate (TFR) BDHS, every 3 years 2.3, BDHS 2014 1.7 GI 5. Prevalence of stunting among under- BDHS, every 3 years; 36.1%, BDHS 2014 25% 5children UESD, every non-DHS years GI 6. Prevalence of diabetes and hypertension BDHS, every 3 years; Dia: 11.2%; Hyp: 31.9%, Dia: 10%; Hyp: among adult women (Estimated as elevated blood NCD-RF, every 2 years BDHS 2011 30% sugar and blood pressure among women and men aged 35 years or older) GI 7. Percentage of public facilities with key BHFS, every 2 years FP: 38.2; ANC 7.8%; CH FP: 70%; ANC service readiness as per approved Essential 6.7%, BHFS 2014 50%; CH 50% Service Package (Defined as facilities (excluding CCs) having: a. for FP: guidelines, trained staff, BP machine, OCP, and condom; b. for ANC: Health Bulletin 2019 Health guidelines, trained staff, BP machine, hemoglobin, and urine protein testing capacity, Fe/folic acid tablets; c. for CH: IMCI guideline and trained staff, child scale, thermometer, growth chart, ORS, zinc, Amoxicillin, Paracetamol, Anthelmintic) Program -

Phone No. Upazila Health Center

gvevBj ÑdvÖb ß^vßå† Ñmev gvevBj ÑdvÖbi gva†Ög bvMwiKMY GLb miKvix ß^vßå† ÑKÖï`¢ Kg°iZ wPwKrmÖKi KvQ Ñ_ÖK webvg~Öj† ß^vßå† civgk° wbÖZ cviÖQb| ÑmRb† evsjvÖ`Öki cŒwZwU ÑRjv DcÖRjv nvmcvZvÖj( ÑgvU 482wU nvmcvZvj) GKwU KÖi ÑgvevBj Ñdvb Ñ`qv nÖqÖQ| AvcwbI GB Ñmev MŒnY KiÖZ cvÖib| Gme ÑgvevBj ÑdvÖbi bú^i ßåvbxq ch°vÖq cŒPvÖii e†eßåv Kiv nÖqÖQ| 24 NïUv e†vcx ÑKvb bv ÑKvb wPwKrmK GB ÑgvevBj ÑdvÖbi Kj wiwmf KÖib| ßåvbxq RbMY Gme ÑgvevBj ÑdvÖb Ñdvb KÖi nvmcvZvÖj bv GÖmB webvg~Öj† wPwKrmv civgk° wbÖZ cvÖib District Upazila Name of Hospitals Mobile No. Dinajpur Birampur Birampur Upazila Health Complex 01730324634 Dinajpur Birganj Birganj Upazila Health Complex 01730324635 Dinajpur Birol Birol Upazila Health Complex 01730324636 Dinajpur Bochaganj Bochaganj Upazila Health Complex 01730324637 Dinajpur Chirirbandar Chirirbandar Upazila Health Complex 01730324638 Dinajpur Fulbari Fulbari Upazila Health Complex 01730324639 Dinajpur Ghoraghat Ghoraghat Upazila Health Complex 01730324640 Dinajpur Hakimpur Hakimpur Upazila Health Complex 01730324641 Dinajpur Kaharol Kaharol Upazila Health Complex 01730324642 Dinajpur Khansama Khansama Upazila Health Complex 01730324643 Dinajpur Nawabganj Nawabganj Upazila Health Complex 01730324644 Dinajpur Parbatipur Parbatipur Upazila Health Complex 01730324645 Dinajpur District Sadar District Hospital 01730324805 District Upazila Name of Hospitals Mobile No. Jessore Abhoynagar Abhoynagar Upazila Health Complex 01730324581 Jessore Bagherpara Bagherpara Upazila Health Complex 01730324582 Jessore Chowgacha Chowgacha Upazila -

List of 50 Bed Hospital

List of 50 Bed UHC No. of Sl. No. Organization Name Division Name District Name Upazila Name Bed 1 Amtali Upazila Health Complex, Barguna Barisal Barguna Amtali 50 2 Betagi Upazila Health Complex, Barguna Barisal Barguna Betagi 50 3 Patharghata Upazila Health Complex, Barguna Barisal Barguna Patharghata 50 4 Agailjhara Upazila Health Complex, Barishal Barisal Barishal Agailjhara 50 5 Gournadi Upazila Health Complex, Barishal Barisal Barishal Gaurnadi 50 6 Muladi Upazila Health Complex, Barishal Barisal Barishal Muladi 50 7 Borhanuddin Upazila Health Complex, Bhola Barisal Bhola Burhanuddin 50 8 Charfession Upazila Health Complex, Bhola Barisal Bhola Charfession 50 9 Daulatkhan Upazila Health Complex, Bhola Barisal Bhola Daulatkhan 50 10 Lalmohan Upazila Health Complex, Bhola Barisal Bhola Lalmohan 50 11 Nalchithi Upazila Health Complex, Jhalokati Barisal Jhalokati Nalchity 50 12 Galachipa Upazila Health Complex, Patuakhali Barisal Patuakhali Galachipa 50 13 Kalapara Upazila Health Complex, Patuakhali Barisal Patuakhali Kalapara 50 14 Mathbaria Upazila Health Complex, Pirojpur Barisal Pirojpur Mathbaria 50 15 Nesarabad Upazila Health Complex, Pirojpur Barisal Pirojpur Nesarabad 50 16 Nasirnagar Upazila Health Complex, Brahmanbaria Chittagong Brahmanbaria Nasirnagar 50 17 Sarail Upazila Health Complex, Brahmanbaria Chittagong Brahmanbaria Sarail 50 18 Haziganj Upazila Health Complex, Chandpur Chittagong Chandpur Hajiganj 50 19 Kachua Upazila Health Complex, Chandpur Chittagong Chandpur Kachua 50 20 Matlab(daxin) Upazila Health Complex, -

Inventory of LGED Road Network, March 2005, Bangladesh

BASIC INFORMATION OF ROAD DIVISION : DHAKA DISTRICT : MYMENSINGH ROAD ROAD NAME CREST TOTAL SURFACE TYPE-WISE BREAKE-UP (Km) STRUCTURE EXISTING GAP CODE WIDTH LENGTH (m) (Km) EARTHEN FLEXIBLE BRICK RIGID NUMBER SPAN NUMBER SPAN PAVEMENT PAVEMENT PAVEMEN (m) (m) (BC) (WBM/HBB/ T BFS) (CC/RCC) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 UPAZILA : NANDAIL ROAD TYPE : UPAZILA ROAD 361722001 Nandail H.Q - Dewanganj G.C Rd. 7.31 17.000.00 17.00 0.00 0.00 38 149.00 0 0.00 361722002 Nandail H.Q - Bakchanda G.C Rd. 7.31 8.800.00 8.80 0.00 0.00 33 83.03 0 0.00 361722003 Madhupur R&H - Dewangonj G.C Rd. 7.31 9.604.50 5.10 0.00 0.00 18 44.60 0 0.00 361722004 Musulli R&H -Tarail GC Rd. 7.31 5.701.20 3.50 1.00 0.00 4 6.98 0 0.00 361722007 Nandail H.Q - Atharabari GC Rd. 7.32 5.270.00 5.27 0.00 0.00 4 9.90 0 0.00 361722008 Kanarampur R&H - Dewanganj GC Road 4.87 11.000.35 2.35 8.30 0.00 8 36.44 0 0.00 UPAZILA ROAD TOTAL: 6 Nos. Road 57.376.05 42.02 9.30 0.00 105 329.95 0 0.00 ROAD TYPE : UNION ROAD 361723003 Majar Bus stand - Moazzempur U.P Rd 4.80 1.500.00 1.50 0.00 0.00 2 4.00 0 0.00 361723004 Kanarampur Bazar - Moazzempur U.P Office Via 4.00 1.151.15 0.00 0.00 0.00 3 5.00 0 0.00 Syedgoan 361723005 Moazzempur U.P - Goras than Bazar Road 4.87 5.000.00 0.30 4.70 0.00 14 18.80 0 0.00 361723006 Jhalua Bazar(Nandail U.P) - Dateratia bazar 4.87 2.502.20 0.30 0.00 0.00 3 6.90 0 0.00 361723007 Nandail U.P (Jalua bazar) - Sherpur Langarpar Bazar 4.87 5.503.50 0.00 2.00 0.00 5 5.45 0 0.00 Rd.