A Local Prison for the Poor. a Study of the Kingston House of Correction, 1762-1852

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 Crystal Palace – Brixton – Trafalgar Square

3 CrystalPalace–Brixton–TrafalgarSquare 3 Mondays to Fridays CrystalPalaceBusStation 0555 0747 0847 1543 1859 1909 1919 1931 1943 1955 CroxtedRoadParkHallRoad 0603 Then 0758 Then 0900 Then 1552 Then 1907 1917 1927 1939 1951 2003 HerneHillStationDulwichRoad 0611 about 0809 about 0913 about 1601 about 1915 1925 1935 1947 1959 2010 BrixtonStation 0619 every7-8 0821 every8-9 0924 every8 1611 every8-9 1924 1934 1944 1956 2008 2018 KenningtonChurch(forOvalStation) 0627 minutes 0831 minutes 0934 minutes 1621 minutes 1934 1944 1954 2006 2017 2027 MillbankLambethBridge 0637 until 0850 until 0945 until 1632 until 1943 1953 2003 2015 2026 2036 TrafalgarSquareCockspurStreet 0644 0901 0957 1644 1952 2002 2010 2022 2033 2043 CrystalPalaceBusStation 2007 2131 2143 2155 2207 2219 2231 2243 2255 2310 2325 2340 2355 CroxtedRoadParkHallRoad 2014 Then 2138 2150 2202 2213 2225 2237 2249 2301 2316 2331 2346 0001 HerneHillStationDulwichRoad 2021 every12 2145 2157 2208 2219 2231 2243 2255 2307 2322 2337 2352 0007 BrixtonStation 2028 minutes 2152 2204 2214 2225 2237 2249 2301 2313 2328 2343 2358 0013 KenningtonChurch(forOvalStation) 2037 until 2201 2212 2222 2233 2245 2257 2307 2319 2334 2349 0004 0019 MillbankLambethBridge 2046 2210 2221 2231 2242 2254 2306 2316 2328 2343 2358 0013 0028 TrafalgarSquareCockspurStreet 2053 2217 2228 2238 2249 2301 2313 2323 2335 2350 0005 0020 0035 3 Saturdays (also Good Friday) CrystalPalaceBusStation 0555 0610 0625 0640 0655 0710 0725 0740 0752 0804 0814 0824 0832 0840 0848 0855 0902 0910 CroxtedRoadParkHallRoad 0602 0617 0632 -

DATES of TRIALS Until October 1775, and Again from December 1816

DATES OF TRIALS Until October 1775, and again from December 1816, the printed Proceedings provide both the start and the end dates of each sessions. Until the 1750s, both the Gentleman’s and (especially) the London Magazine scrupulously noted the end dates of sessions, dates of subsequent Recorder’s Reports, and days of execution. From December 1775 to October 1816, I have derived the end dates of each sessions from newspaper accounts of the trials. Trials at the Old Bailey usually began on a Wednesday. And, of course, no trials were held on Sundays. ***** NAMES & ALIASES I have silently corrected obvious misspellings in the Proceedings (as will be apparent to users who hyper-link through to the trial account at the OBPO), particularly where those misspellings are confirmed in supporting documents. I have also regularized spellings where there may be inconsistencies at different appearances points in the OBPO. In instances where I have made a more radical change in the convict’s name, I have provided a documentary reference to justify the more marked discrepancy between the name used here and that which appears in the Proceedings. ***** AGE The printed Proceedings almost invariably provide the age of each Old Bailey convict from December 1790 onwards. From 1791 onwards, the Home Office’s “Criminal Registers” for London and Middlesex (HO 26) do so as well. However, no volumes in this series exist for 1799 and 1800, and those for 1828-33 inclusive (HO 26/35-39) omit the ages of the convicts. I have not comprehensively compared the ages reported in HO 26 with those given in the Proceedings, and it is not impossible that there are discrepancies between the two. -

Abbess Close, Tulse Hill, London, SW2 £360,000 Leasehold

Abbess Close, Tulse Hill, London, SW2 £360,000 Leasehold Purpose built apartment Modern family bathroom suite Two double bedrooms Large living and entertaining area Neutral decor Separate W/C Bright and spacious throughout Private balcony Contemporary fitted kitchen Parking available 2, Lansdowne Road, Croydon, London, CR9 2ER Tel: 0330 043 0002 Email: [email protected] Web: www.truuli.co.uk Abbess Close, Tulse Hill, London, SW2 £360,000 Leasehold **Vendor Comments** "We really love this flat. The neighbourhood is quiet, despite being near so many amenities. Since we bought it five years ago we’ve put in a new kitchen & bathroom; painted & wallpapered all the walls and carpeted & tiled every floor. We left here to get married and brought our baby home here. We hosted our parents for Christmas dinner and had sun-downers on the balcony in the summer. The location is ideal, near Tulse Hill, Herne Hill and West Norwood stations. We’re 20 minutes from central London via Tulse Hill station or 35 minutes via bus and Brixton tube station. We get to park outside our flat permitting and cost free too, which is a plus. We know and talk to all our neighbours in our small block and 3 years ago the residents association was setup. There’s also a community hall for hire which is very nearby where we hosted our baby's christening party. We’re a 5 minute walk from Brockwell park with its picnic spots, lido, miniature railway and park runs. There’s the Tulse Hill Hotel for lunch or a drink and two breweries next to the park (Bullfinch & Canopy). -

Brand New 19,000 Sq Ft Grade a Office

BRAND NEW 19,000 SQ FT GRADE A OFFICE 330 CLAPHAM ROAD•SW9 If I were you... I wouldn’t settle for anything less than brand new Let me introduce you to LUMA. 19,000 sq ft of brand new premium office space conveniently located just a short stroll from Stockwell and Clapham North underground stations. If I were you, I know what I would do... 330 Clapham Road SW9 LUMA • New 19,000 sq ft Office HQ LUMA • New 330 Clapham Road SW9 LUMA • New 19,000 sq ft Office HQ LUMA • New I’d like to see my business in a new light Up to 19,000 sq ft of Grade A office accommodation is available from lower ground to the 5th floor, benefiting from excellent views and full height glazing. 02 03 A D R O N D E E A M I L 5 1 Holborn 1 A E D G W £80 per sq ft A R E R O A City of London D Soho A 1 3 C O M M E Poplar R C I A L R City O A D D £80 per sq ft A O White City R A 1 2 0 3 T H E H I G H W A Y Mayfair E Midtown G D Hyde I R Park B £80 per sq ft R E W O T 0 0 A 3 Holland 1 3 A 2 0 Park St James Waterloo Park Southwark D £71 per sq ft A O R L £80 per sq ft L E W M O R Westminster C E S T A 4 W O A D per sq ft W E S T C R O M W E L L R £75 Vauxhall Belgravia £55 per sq ft D V 330 Clapham Road SW9 A R U Isle of Dogs Pimlico X K H R A L A L P B R N I A D O 2 G E T N G E W N I C auxa R D N O R O A S O R N S S V E N E R R O K O G A 2 1 2 D A 3 3 A B Oa A A 2 T 0 Oval T 3 LUMA • New 19,000 sq ft Office HQ LUMA • New Battersea E R S S Battersea E L £50 per sq ft A Park £50 per sq ft A M A Fulham B 2 R B 0 D D E 2 I A D O T A C G R H A K O M E R R A R B P E D R A R N W D E Peckham R S E E T O L A T L B T 5 N E 2 0 X W R O 3 I A D A R B D per Camberwell I’d want my business A 3 O £45 sq ft 2 R A A tocwe 3 andswort S located in Central London’s 2 R 2 A oad 0 D E Louborou E most cost effective C L unction S 6 P 1 E 2 T R 3 A L U C Capam R I H C H T A U O S 5 R i t. -

Different Faces of One ‘Idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek

Different faces of one ‘idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek To cite this version: Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek. Different faces of one ‘idea’. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow. A systematic visual catalogue, AFM Publishing House / Oficyna Wydawnicza AFM, 2016, 978-83-65208-47-7. halshs-01951624 HAL Id: halshs-01951624 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01951624 Submitted on 20 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow A systematic visual catalogue Jean-Yves BLAISE Iwona DUDEK Different faces of one ‘idea’ Section three, presents a selection of analogous examples (European public use and commercial buildings) so as to help the reader weigh to which extent the layout of Krakow’s marketplace, as well as its architectures, can be related to other sites. Market Square in Krakow is paradoxically at the same time a typical example of medieval marketplace and a unique site. But the frontline between what is common and what is unique can be seen as “somewhat fuzzy”. Among these examples readers should observe a number of unexpected similarities, as well as sharp contrasts in terms of form, usage and layout of buildings. -

Visiting Artists

Welcome Pack VISITING ARTISTS Hello! Streatham Space Project is a new live performance venue, purpose-built for Streatham and Greater London. The venue includes a 123 seat fully-flexible auditorium for theatre, music, comedy, dance and family friendly activities; a rehearsal room for dance classes, yoga, theatre workshops as well as plenty more; and a buzzing café and bar area. Streatham Space Project is an experiment in what an arts space can do for a neighbourhood like Streatham and the wider London community. Enclosed you will find information about Streatham Space Project including travel, contact and access information. We look forward to welcoming you soon! X The SSP Team CONTACT INFO Executive Director Lucy Knight – [email protected] Venue and Operations Manager Lexie McDougall – [email protected] Marketing Ella Kilford – [email protected] Production Manager [email protected] 1 GETTING HERE Address: Streatham Space Project Sternhold Avenue London, SW2 4PA TRANSPORT Tube/Bus The nearest tube stations are Brixton, Balham and Tooting Bec. The nearest bus stop is Streatham Hill/Streatham Hill Station. From Brixton busses 109, 118, 133, 159, 250 and 333 run towards Streatham Hill Station From Tooting Bec bus route 319 runs towards Streatham Hill Station From Balham bus route 255 runs towards Streatham Hill Station Rail Streatham Hill Station is a 1-minute walk from Streatham Space Project and runs towards London Bridge and Victoria Streatham Station is 15-minute walk to Streatham Space Project along Streatham High Road Bike There are bike racks along Streatham High Road, there is currently no bike parking at Streatham Space Station and bikes should not be brought into the building Car Parking Streatham Space Project has no parking spaces available on site. -

Low Cost/No Cost Family Fun in London Please Look at Organisations’ Websites to Double Check Times and Arrangements

Low Cost/No Cost Family Fun in London Please look at organisations’ websites to double check times and arrangements London Open House weekend 22 and 23 September – locations across London Open House London is the world’s largest architectural festival, giving FREE public access to 800+ buildings, walks, talks and tours over one weekend in September each year. To find out what’s happening visit: www.openhouselondon.org.uk Examples include: Kia Oval (Surrey Cricket Ground), SE11 5SS Saturday 21 September 10am – 5pm. The Edible Bus Stop Studio, Arch 511, Ridgway Road, SW9 7EX Sunday 22 September 2 – 6pm A former mechanics garage, refurbished, utilising reclaimed and recycled materials to create a design studio and workshop. Brixton Windmill, Blenheim Gardens, Brixton Hill SW2 5EU 21 and 22 September 1 – 4.30pm The only surviving windmill in inner London, built in 1816. Guided tours of the exterior and first two floors, bookable through the website. Please note that the flors beyond the first floor are accessed by steep ladder-stairs, children must be over 1.2m in height. Lambeth Tower Hall 21 and 22 September - 10am – 5pm Warwick & Austin Hall Landmark Edwardian Baroque style town hall in red brick and Portland stone. striking new atrium, reception and courtyard space along with grand marble lined staircase and ornate council chamber. Grade 2 listed. National Theatre, Upper Ground, South Bank, SE1 9PX 21 September 10am -5pm and 22 September 12.15-5pm Housing one of the world’s most important producing theatres! The building is a key work in British Modernism with three theatres, designed with workshops and theatre-making all on site. -

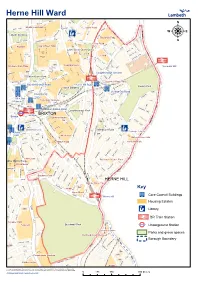

Herne Hill Ward AY VEW RO C B G O D R U OA M PS R O TA R N L D D L T S a YN T OST N O

Herne Hill Ward AY VEW RO C b G O D R U OA M PS R O TA R N L D D L T S A YN T OST N O M R S A T M T E L R M A PL E A W R R L N O Myatts Field South R S O K O OAD RT A T Paulet Road T E R R U C B A D E P N N N R T E LO C L A C R L L E D T D R A T S R U R E K E R B I L O E B N E H PE A L NFO U A L C R D M W D A S D T T A P A Y N A R A W Slade Gardens R O N V E C O E A K R K D L A D P H C L Thorlands TMO A RO R AD B UGH ORD O EET RO LILF ROA U TR HBO D R S G K RT OU E SA L M B T N C O M R S D I A B A A N L U L O E SPICE E Lilford Road D R R R D R : T E A Y E T D O C R CLOSE E A R R N O O Angell Town TMO Sch R S A S T M C A Robsart Y L O T E A E A I V D R L N D R W E C F A R O E R E O L V T A I L R T O F L N D A Elam Street Open Space D N E L R V E R AC O A PL O FERREY O R B D H A U O R N A S U D TO MEWS G A I AY T Sch N D L O D A H I C WYNNE T D L K Hertford E B A W N O W O E E V R L I N RD SERENADERS Lilford R GR L O A R N A Y E P N O T A MEWS E M N A O R S A E U O W D S S U K S W R M T I S O C N T R G E A G K L X B O T L R A H E W K ROAD R A P U A K R O D R O E S L A DN O U D D G F R O O A D B R V L A Sch U A U X G Loughborough O H H D R R A Stockwell Park TMO AN D D N A GE F S L O Denmark Hill L E T L S R A R O T T E Y E L L T C H RK R E E A A O Y S R OAD L P A B VILLA R EL S D R G O G N M D D U N E M R Sch A RD A N D R A E G L R S D W L L R A O Y S L SE M A Loughborough Junction UM B S E R E F T D D N Y N W E R C F E R C O I S A H D E E I A L R M T C C D D T S U W B Max Roach Park R R R I O G N A P D A I D F G S T 'S O D A N N H E S -

Lambeth's Creative & Digital Industries Strategy for Growth

Creative ways to grow. Lambeth’s Creative & Digital Industries Strategy for Growth Contents Foreword 3 Our vision 4 Our strategy 7 Building on our strengths 19 Meeting the challenges 31 Making it happen 56 Working in partnership 69 ActionSpace Lambeth’s Creative & Digital Industries Strategy for Growth 1 Foreword For the first time the council has taken a look at the current performance and future potential of Lambeth as a creative and digital hub. Our strategy identifies the opportunities and threats; the benefits of growth for our our residents, businesses and places; and how we can encourage and support this dynamic sector. It is the result of truly co-productive work. Over many months we have brought together creative and digital businesses, education providers, trade bodies, young residents, thought leaders and social entrepreneurs. We have explored individual and collective ambitions. We have recognised the challenges and how we might achieve success. Now we have the foundation and commitment to make Lambeth the next destination and, in time, leader for London’s creative and digital economy. Lambeth Council has a pivotal role to play in growing the sector. It has a unique opportunity. We welcome, encourage and work in partnership with businesses and we expect that collaboration to benefit our community. Lambeth has all the right elements to build thriving and sustainable creative and digital clusters. Our strategy is a clear commitment to achieve this aim. It fits within the borough’s Strategic Plan, Future Lambeth, which draws on Lambeth’s strengths, potential and values to transform its goals into reality. -

Trams in Brixton 1870 - 1951

TRAMS IN BRIXTON 1870 - 1951 Horse Trams Two Acts of Parliament, passed in 1869 and 1870, empowered the Metropolitan Street Tramways Company to construct tramways from the Lambeth end of Westminster Bridge to Brixton and to Clapham. The company got to work quickly; they lost no time in laying down double tracks with rails level with the surface of the road. 2 May 1870 was an important day in Brixton's history. It was the day when the first authorised tramcars operated in London. 1 The new trams ran that day from the Horns Tavern in Kennington Road and along Brixton Road as far as its junction with Stockwell Road. The smart blue tramcars were hauled by two horses. Cars seated 22 persons inside and 24 on the open top deck. The passengers inside sat on red velvet cushions. For top deck passengers were two wooden benches running the length of the tram; these passengers faced outwards. Trams ran every five minutes. The normal fare was a penny a mile but Parliament had required special trams to be run for workmen in the morning and evenings at a halfpenny a mile.2 As soon as the 1870 Act was passed more track laying was rushed on with, and by the end of 1870 trams were in service from the Lambeth end of Westminster Bridge to St Matthew's church, Brixton, and another line ran along Clapham Road to the Swan at Stockwell. During 1871 tramcars had reached the Plough at Clapham, and the Brixton Line had been extended to the junction of Brixton Water Lane. -

Brixton and Clapham Park PCN Patient Group Meeting

Brixton and Clapham Park PCN Patient group meeting Notes of meeting held on Zoom 14 April 2021. Present: Nicola Kingston (Chair), Dr Jennie Parker (Chair of PCN, Hetherington), Dave Ball, Ros Borley, Pippa Cardale, Jenny Cobley, Mr & Mrs Day, Craig Givens, Lucy Ismail, Christine Jacobs, Ernestine Montgomerie, Chris Newman (Managing Partner, Clapham Park), Rebecca McNair, Liz Dunbar, Rev Funke Ogbede, Esigbemi Osoba, Martin Pratt, David Ritchie, Maureen Simpson, Sara Taffinder, Peter Woodward. Apologies: Dr Andrew Boyd (Clapham Park), Barbara Wilson, Paulina Tamborrel Signoret (Citizens UK Lambeth). 1. Welcome and introductions. Nicola welcomed everyone and introductions were made. Jenny Cobley agreed to take the notes. 2. Update on the Covid Vaccination programme and surge testing for Covid variants. Dr Jennie Parker reported on the vaccination programme, which is going smoothly at Hetherington Group Practice (HGP), where they now have cover over the waiting area outside. The final delivery of Pfizer vaccine for second doses was due this weekend . The Oxford Astra Zeneca (OAZ) vaccine would also be available for second doses next week, and for those in groups 1-9 who have not yet had the vaccine and for those 45+ years. Chris Newman is organising the vaccination team, they are training more staff, St John’s ambulance personnel and medical students as vaccinators, as the vaccination programme is likely to continue for some months. There is always a lead GP on duty. An increase in uptake among ethnic minority groups has been seen in our area. Uptake of vaccines is 77% overall, with 89% among white, 81% Asian and 65% black patients. -

In Jail with Charles Dickens (1896)

fCROFOUMED BY PRESERVATION €. ii'4 ¥ I DATE.:.!FCll 2.1..1987. itt iatt wUto ffiteleu / / Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with fundiri^ from UnjA^rsity of : Toronto _ https://archive.org/details/injailwithcharlOOtrum IN JAIL WTTH Charles Dickens BY ALFRED TRUMBLE Editor of The Collector ’• MiCROFORMED o' PRESSRVATIOM SERVICES yUL 2 1 1987 DATE London SUCKLING & GALLOWAY 1896 Printed in America. INTRODUCTORY. EADERS of Charles Dickens must all have remarked the deep and abiding Interest he took in that grim accessory to civili- zation, the prison. He not only went jail hunt- ing whenever opportunity offered, but made a profound study of the rules, practices, and abuses of these institutions. Penology was, in fact, one of his hobbies, and some of the most powerful passages in his books are those which have their scene of action laid within the shadow of the gaol. It was this fact which led to the compilation of the papers comprised in the present volume. The writer had been a student of Dickens from the days when the publication of his novels in serial form was a periodical event. When he first visited England, many of the landmarks which the novelist had, in a manner, made historical, were still in existence, but of the principal prisons which figure in his works Newgate was the only one which existed in iv Introductory. any approximation to its integrity. The Fleet and the King’s Bench were entirely swept away; of the Marshalsea only a few buildings remained, converted to ordinary uses. In this country, however, the two jails which interested him, still remain, with cer- tain changes that do not impair their general conformance to his descriptions.