CEDAR ISLAND NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Carteret County, North Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sorted by Facility Type.Xlsm

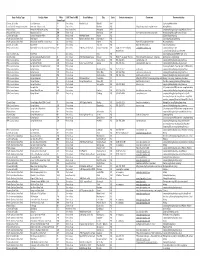

Basic Facility Type Facility Name Miles AVG Time In HRS Street Address City State Contact information Comments Known activities (from Cary) Comercial Facility Ace Adventures 267 5 hrs or less Minden Road Oak Hill WV Kayaking/White Water East Coast Greenway Association American Tobacco Trail 25 1 hr or less Durham NC http://triangletrails.org/american- Biking/hiking Military Bases Annapolis Military Academy 410 more than 6 hrs Annapolis MD camping/hiking/backpacking/Military History National Park Service Appalachian Trail 200 5 hrs or less Damascus VA Various trail and entry/exit points Backpacking/Hiking/Mountain Biking Comercial Facility Aurora Phosphate Mine 150 4 hrs or less 400 Main Street Aurora NC SCUBA/Fossil Hunting North Carolina State Park Bear Island 142 3 hrs or less Hammocks Beach Road Swannsboro NC Canoeing/Kayaking/fishing North Carolina State Park Beaverdam State Recreation Area 31 1 hr or less Butner NC Part of Falls Lake State Park Mountain Biking Comercial Facility Black River 90 2 hrs or less Teachey NC Black River Canoeing Canoeing/Kayaking BSA Council camps Blue Ridge Scout Reservation-Powhatan 196 4 hrs or less 2600 Max Creek Road Hiwassee (24347) VA (540) 777-7963 (Shirley [email protected] camping/hiking/copes Neiderhiser) course/climbing/biking/archery/BB City / County Parks Bond Park 5 1 hr or less Cary NC Canoeing/Kayaking/COPE/High ropes Church Camp Camp Agape (Lutheran Church) 45 1 hr or less 1369 Tyler Dewar Lane Duncan NC Randy Youngquist-Thurow Must call well in advance to schedule Archery/canoeing/hiking/ -

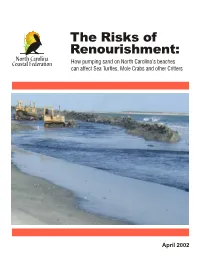

How Pumping Sands on NC Beaches

The Risks of Renourishment: North Carolina Coastal Federation How pumping sand on North Carolina’s beaches can affect Sea Turtles, Mole Crabs and other Critters April 2002 Who We Are The North Carolina Coastal Federation (NCCF) is the state’s largest non-profit organization working to restore and protect the coast. NCCF headquarters are at 3609 Highway 24 in Ocean between Morehead City and Swansboro and are open Monday through Friday. The headquarters houses NCCF’s main offices, a nature shop, library, and information area. NCCF also operates a field office at 3806-B Park Avenue in Wilmington. For more information call 252-393-8185 or visit our website at www.nccoast.org. This report was written by Ted Wilgis, the Federation’s Cape Fear Coastkeeper, and edited by Frank Tursi, the Cape Lookout Coastkeeper, and Jim Stephenson, Program Analyst. All are closely monitoring beach renourishment projects in North Carolina during the time covered in this report. Wilgis and Tursi also took all of the photographs. Cover Photo Bulldozers work the new sand being pumped onto the beach at Fort Macon State Park in Carteret County. 2 Index Executive Summary.................................................4 Recommendations....................................................5 Background..............................................................6 Sea Turtles ........................................................ 7-11 Mole Crabs and Other Critters...............................12 Other Effects ..........................................................13 -

North Carolina STATE PARKS

North Carolina STATE PARKS North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development Division of State Parks North Carolina State Parks A guide to the areas set aside and maintained taining general information about the State as State Parks for the enjoyment of North Parks as a whole and brief word-and-picture Carolina's citizens and their guests — con- descriptions of each. f ) ) ) ) YOUR STATE PARKS THE STATE PARKS described in this well planned, well located, well equipped and booklet are the result of planning and well maintained State Parks are a matter of developing over a number of years. justifiable pride in which every citizen has Endowed by nature with ideal sites that a share. This is earned by your cooperation range from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean in observing the lenient rules and leaving the to the tops of the Blue Ridge Mountains, facilities and grounds clean and orderly. the State has located its State Parks for easy Keep this guide book for handy reference- access as well as for varied appeal. They use your State Parks year 'round for health- offer a choice of homelike convenience and ful recreation and relaxation! comfort in sturdy, modern facilities . the hardy outdoor life of tenting and camp cook- Amos R. Kearns, Chairman ing ... or the quick-and-easy freedom of a Hugh M. Morton, Vice Chairman day's picnicking. The State Parks offer excel- Walter J. Damtoft lent opportunities for economical vacations— Eric W. Rodgers either in the modern, fully equipped vacation Miles J. Smith cabins or in the campgrounds. -

North Carolina's State Parks: Disregarded and in Disrepair

North Carolina's State Parks: Disregarded and in Disrepair By Bill Krueger and Mike McLaughlin More than seven million people visit North Carolina's state parks and recreation areas each year-solid evidence that the public supports its state park system. But for years, North Carolina has routinely shown up at or near the bottom in funding for parks, and its per capita operating budget currently ranks 49th in the nation. Some parks are yet to be opened to the public due to lack of facilities, and parts of other parks are closed because existing facilities are in a woeful state of disrepair. Indeed, parks officials have identified more than $113 million in capital and repair needs, nearly twice as much as has been spent on the parks in the system's 73-year history. Just recently, the state has begun making a few more gestures toward improving park spending. But the question remains: Will the state commit the resources needed to overcome decades of neglect? patrol two separate sections of the park, pick up highway in the narrowing strip of unde- trash, clean restrooms and bathhouses, and main- veloped property that separates the bus- tain dozens of deteriorating buildings . "I've got a Wedgedtling citiesbetween of Raleigh aninterstate and Durhamanda major lies a total of 166 buildings - most of them built between refuge from commercialization called William B. 1933 and 1943," says Littrell. "I've got buildings Umstead State Park. with five generations of patches- places where The 5,400-acre oasis has become an easy re- patches were put on the patches that were holding treat to nature in the midst of booming growth. -

North Carolina Parks for Kids

north carolina parks for kids 1. Great Smoky Mountains National Park Hike to the observation platform on the top of Cling- mans Dome or lean about history in the Mountain Farm Museum. Ride your bike along Cades Cove Buddy Bison’s Loop then go fishing or look for salamanders! Fact Bites! 2. Grandfather Mountain Look out for owls and other birds of prey and see • North Carolina is the leading rare wildflowers. Hike over the mile high swinging producer of sweet potatoes in bridge or tour the nature museum. the United States. The vegetable is a native crop to the state and 3. Pisgah National Forest 6. Hammocks Beach State Park www.parktrust.org in 1995, it was recognized as the Explore the park’s waterfalls, including Sliding Rock, Kayak, canoe, or paddleboard to Bear Island. Build Official Vegetable of the state! a 60-foot natural water slide! Fish along the French a sand castle or enjoy a picnic. Go fishing, take the Broad River and picnic. Check out the Visitor Center ferry, and look for -- but don’t disturb -- the logger- and learn about this “Cradle of Forestry!” head turtles! • The state’s slogan is “First in Flight”. The Wright brothers brought this honor with their 4. Hanging Rock State Park 7. Fort Macon State Park first launch of a mechanically Dip your feet in the waters at the base of the Lower Go to the Visitor Center to learn about local ecology then learn about the history of the fort on propelled airplane in 1903. Cascades Waterfall then check out the view from the Observation Tower. -

White Oakriver

RIVER WHITE OAK BASIN Tucked between the eastern portions of the Neuse and Cape Fear river basins, the White Oak River Basin abounds with coastal and freshwater wetlands. The basin includes four separate river systems, or subbasins, that feed into highly productive estuaries of Back, Core and Bogue sounds. profile: Core Sound produces the most valuable Total miles of streams and rivers: seafood catch in the basin, followed by 446 Bogue Sound and the Newport River. Total acres of The New River subbasin (not to be confused estuary: 130,009 with the New River Basin in the northwestern Total miles of part of the state) is the largest and most populated of the White Oak River Basin. It contains coastline: 91 the city of Jackson ville and the U.S. Marine Corps base at Camp Lejeune. But the basin draws Municipalities its name from the White Oak River, a remote, scenic, 48-mile river that spills into Bogue Sound within basin: 16 past the picturesque town of Swansboro. Still farther east is the basin’s Newport River, which Counties begins near Havelock and flows into the eastern end of Bogue Sound. The shortest and eastern - within basin: 4 most river in the basin is the North River, which empties into Back Sound near Harkers Island. Size: 1,264 square miles Forest and wetlands—both privately and publicly owned—cover almost half the basin. More Population: than 80,000 acres of the Croatan National Forest lie within the White Oak River Basin. It 150,501 hosts the largest population of carnivorous plants of any national forest and is the second largest (2000 U.S. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G3862 SOUTHERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3862 FEATURES, ETC. .C55 Clayton Aquifer .C6 Coasts .E8 Eutaw Aquifer .G8 Gulf Intracoastal Waterway .L6 Louisville and Nashville Railroad 525 G3867 SOUTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3867 FEATURES, ETC. .C5 Chattahoochee River .C8 Cumberland Gap National Historical Park .C85 Cumberland Mountains .F55 Floridan Aquifer .G8 Gulf Islands National Seashore .H5 Hiwassee River .J4 Jefferson National Forest .L5 Little Tennessee River .O8 Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail 526 G3872 SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3872 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .B6 Blue Ridge Mountains .C5 Chattooga River .C52 Chattooga River [wild & scenic river] .C6 Coasts .E4 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Area .N4 New River .S3 Sandhills 527 G3882 VIRGINIA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G3882 .A3 Accotink, Lake .A43 Alexanders Island .A44 Alexandria Canal .A46 Amelia Wildlife Management Area .A5 Anna, Lake .A62 Appomattox River .A64 Arlington Boulevard .A66 Arlington Estate .A68 Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial .A7 Arlington National Cemetery .A8 Ash-Lawn Highland .A85 Assawoman Island .A89 Asylum Creek .B3 Back Bay [VA & NC] .B33 Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge .B35 Baker Island .B37 Barbours Creek Wilderness .B38 Barboursville Basin [geologic basin] .B39 Barcroft, Lake .B395 Battery Cove .B4 Beach Creek .B43 Bear Creek Lake State Park .B44 Beech Forest .B454 Belle Isle [Lancaster County] .B455 Belle Isle [Richmond] .B458 Berkeley Island .B46 Berkeley Plantation .B53 Big Bethel Reservoir .B542 Big Island [Amherst County] .B543 Big Island [Bedford County] .B544 Big Island [Fluvanna County] .B545 Big Island [Gloucester County] .B547 Big Island [New Kent County] .B548 Big Island [Virginia Beach] .B55 Blackwater River .B56 Bluestone River [VA & WV] .B57 Bolling Island .B6 Booker T. -

Nc State Parks

GUIDE TO NC STATE PARKS North Carolina’s first state park, Mount Mitchell, offers the same spectacular views today as it did in 1916. 42 OUR STATE GUIDE to the GREAT OUTDOORS North Carolina’s state parks are packed with opportunities: for adventure and leisure, recreation and education. From our highest peaks to our most pristine shorelines, there’s a park for everyone, right here at home. ACTIVITIES & AMENITIES CAMPING CABINS MILES 5 THAN MORE HIKING, RIDING HORSEBACK BICYCLING CLIMBING ROCK FISHING SWIMMING SHELTER PICNIC CENTER VISITOR SITE HISTORIC CAROLINA BEACH DISMAL SWAMP STATE PARK CHIMNEY ROCK STATE PARK SOUTH MILLS // Once a site of • • • CAROLINA BEACH // This coastal park is extensive logging, this now-protected CROWDERSMOUNTAIN • • • • • • home to the Venus flytrap, a carnivorous land has rebounded. Sixteen miles ELK KNOB plant unique to the wetlands of the of trails lead visitors around this • • Carolinas. Located along the Cape hauntingly beautiful landscape, and a GORGES • • • • • • Fear River, this secluded area is no less 2,000-foot boardwalk ventures into GRANDFATHERMOUNTAIN • • dynamic than the nearby Atlantic. the Great Dismal Swamp itself. HANGING ROCK (910) 458-8206 (252) 771-6593 • • • • • • • • • • • ncparks.gov/carolina-beach-state-park ncparks.gov/dismal-swamp-state-park LAKE JAMES • • • • • LAKE NORMAN • • • • • • • CARVERS CREEK STATE PARK ELK KNOB STATE PARK MORROW MOUNTAIN • • • • • • • • • WESTERN SPRING LAKE // A historic Rockefeller TODD // Elk Knob is the only park MOUNT JEFFERSON • family vacation home is set among the in the state that offers cross- MOUNT MITCHELL longleaf pines of this park, whose scenic country skiing during the winter. • • • • landscape spans more than 4,000 acres, Dramatic elevation changes create NEW RIVER • • • • • rich with natural and historical beauty. -

North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation Contact Information for Individual Parks

North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation Contact information for individual parks Parks A to K CAROLINA BEACH State Park CARVERS CREEK State Park CHIMNEY ROCK State Park 910-458-8206 910-436-4681 828-625-1823 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] P.O. Box 475 2505 Long Valley Road P.O. Box 220 Carolina Beach, NC 28428 Spring Lake, NC 28390 Chimney Rock, NC 28720 CLIFFS OF THE NEUSE State Park CROWDERS MOUNTAIN State Park DISMAL SWAMP State Park 919-778-6234 704-853-5375 252-771-6593 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 240 Park Entrance Road 522 Park Office Lane 2294 U.S. 17 N. Seven Springs, NC 28578 Kings Mountain, NC 28086 South Mills, NC 27976 ELK KNOB State Park ENO RIVER State Park FALLS LAKE State Rec Area 828-297-7261 919-383-1686 919-676-1027 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 5564 Meat Camp Road 6101 Cole Mill Road 13304 Creedmoor Road Todd, NC 28684 Durham, NC 27705 Wake Forest, NC 27587 FORT FISHER State Rec Area FORT MACON State Park GOOSE CREEK State Park 910-458-5798 252-726-3775 252-923-2191 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1000 Loggerhead Road 2303 E. Fort Macon Road 2190 Camp Leach Road Kure Beach, NC 28449 Atlantic Beach, NC 28512 Washington, NC 27889 GORGES State Park GRANDFATHER MTN State Park HAMMOCKS BEACH State Park 828-966-9099 828-963-9522 910-326-4881 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 976 Grassy Ridge Road P.O. -

Environmental Assessment for 2018 Hurricane Recapitalization Of

DRAFT Environmental Assessment for 2018 Hurricane Recapitalization of Station Fort Macon United States Coast Guard Sector Field Office Fort Macon Atlantic Beach, North Carolina A/E CONTRACT NUMBER: 70Z05018DAECOMT06 TASK ORDER NUMBER: 70Z08320FPAC07800 CG SFRL P/N: 13823167 U.S. COAST GUARD CIVIL ENGINEERING UNIT 1240 EAST NINTH STREET, RM 2179 CLEVELAND, OHIO 44199-2060 AECOM 1300 East Ninth Street, Suite 500 Cleveland, OH 44114 Tel: 216.622.2300 June 2020 This page intentionally left blank. US Coast Guard Station Fort Macon Atlantic Beach, NC Executive Summary 1 Executive Summary 2 ES. 1 Introduction 3 This Environmental Assessment (EA) has been prepared in accordance with the National Environmental Policy 4 Act of 1969 (NEPA; 42 United States Code [USC] §§ 4321 et seq.); the President’s Council on Environmental 5 Quality (CEQ) Regulations Implementing the Procedural Provisions of NEPA (40 Code of Federal Regulations 6 [CFR] Parts 1500-1508); Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Management Directive 023-01, 7 Implementation of NEPA; and Coast Guard Commandant Instruction (COMDTINST) 5090.1, U.S. Coast 8 Guard Environmental Planning Policy. 9 This EA evaluates the environmental effects of the United States Coast Guard’s (USCG) proposal to 10 recapitalize hurricane-damaged facilities (Proposed Action) and its alternatives. The information and analysis 11 contained within this EA will determine whether implementation of the Proposed Action would have a 12 significant impact on the environment, requiring preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). If 13 no significant impacts would occur, a Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) would be appropriate. 14 ES. 2 Scope of the Environmental Assessment 15 This EA evaluates the potential environmental effects of implementing the Proposed Action and reasonable 16 alternatives. -

Environmental Education Centers in NC Guide

AgapeCenter for Environmental Education (ACE Education), Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, Allison Woods Foundation, American Livestock Breeds Conservancy, Backcountry Outdoor Education Center, Betsy-Jeff Penn4-H Educational Center,Blue Jay Center for Environmental Education, Blue Ridge Assembly Environmental Education Center, Blue Ridge Parkway, Camp Broadstone, Camp Cheerio, Camp Chestnut Ridge, Camp Sea Gull & Seafarer - Extended Season Programs, Camp Thunderbird Environmental Education Center, Cape Fear Botanical Garden, Cape Fear Museum, Cape Fear River Watch, Inc., Cape Lookout National Seashore, Carl Furr Planetarium and Environmental Resource Center, Carnivore Preservation Trust, Carolina Beach State Park, Carolina Raptor Center, Catawba College, Center for the Environment, Catawba Science Center, Chimney Rock Park, Clark Park Nature Center, Clemmons Educational State Forest, Cliffs of the Neuse State Park Natural and Cultural History Museum, Colbum Gem and Mineral Museum, Columbia Theater Cultural Resources Center, Crowders Mountain State Park, Dan Nicholas Park Nature Center, Daniel Stowe Botanical Garden, Davie Soil and Water Conservation District- KIT (Keep in Touch) with Your Natural Resources, Discovery Place, Don Lee Center, Duke Power State Park, Durant Nature Park, Eagle's Nest Camp, Earthshine Mountain Lodge, Edenton National Fish Hatchery, Energy Explorium, Eno River State Park, m . -. n. -3, cn I .. FallingCreek Camp " * ' " ' ,. jca Historic Site, Fort mvlronrnenrar taucarion benrers pocks Beach State ~ ~~ -

In North Carolina State Parks Jean Lynch, Coastal Region Biologist Eight NC DPR Parks Working on Phragmites Australis Control

Control of Invasive Common Reed (Phragmites Australis) in North Carolina State Parks Jean Lynch, Coastal Region Biologist Eight NC DPR Parks working on Phragmites australis control •Carolina Beach •Fort Fisher •Fort Macon •Goose Creek •Hammocks Beach •Jockey’s Ridge •Pettigrew •Run Hill Acreage Estimates Carolina Beach State Park: 16 acres Fort Fisher State Recreation Area: 4 acres Fort Macon State Park: ½ acre Goose Creek State Park: 5 acres Hammocks Beach State Park: ½ acre Jockey’s Ridge State Park: 1 acre Pettigrew State Park: 5 acres* Run Hill State Natural Area: 10 acres Total: 42 acres *Phragmites very rapidly colonized the Lake Phelps shoreline after the 2008 Evans Road Fire and resulting low water levels. Mapping Planning GOCR PHRAGMITES CONTROL SITE PLAN: EXISTING PATCHES This section addresses work that will be done by DPR and DWR on the 4 identified Phragmites australis patches in the park. The plan should be updated as new patches are identified. Refer to the attached map for the location of patches. IMPORTANT NOTE ON PREVENTION All infested areas may be prone to reinvasion by Phragmites and to invasion by other exotics as well. It is extremely important that equipment and shoes are cleaned of mud or any other material that may contain seeds or other plant propagules, both before and after work in an infested area. MANAGEMENT GOALS Table 1 states a management goal for each patch, based on its condition, available resources, and the likelihood of success. Eradication should be possible in the long term. Priority is based on the threat posed by the patch and the likelihood of success.