Theatre Architecture As Embodied Space: a Phenomenology of Theatre Buildings in Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing Alberta POD EPDF.Indd

WRITING ALBERTA: Aberta Building on a Literary Identity Edited by George Melnyk and Donna Coates ISBN 978-1-55238-891-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. If you want to reuse or distribute the work, you must inform its new audience of the licence terms of this work. -

Sheila Watson Fonds Finding Guide

SHEILA WATSON FONDS FINDING GUIDE SPECIAL COLLECTIONS JOHN M. KELLY LIBRARY | UNIVERSITY OF ST. MICHAEL’S COLLEGE 113 ST. JOSEPH STREET TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA M5S 1J4 ARRANGED AND DESCRIBED BY ANNA ST.ONGE CONTRACT ARCHIVIST JUNE 2007 (LAST UPDATED SEPTEMBER 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS TAB Part I : Fonds – level description…………………………………………………………A Biographical Sketch HiStory of the Sheila WatSon fondS Extent of fondS DeScription of PaperS AcceSS, copyright and publiShing reStrictionS Note on Arrangement of materialS Related materialS from other fondS and Special collectionS Part II : Series – level descriptions………………………………………………………..B SerieS 1.0. DiarieS, reading journalS and day plannerS………………………………………...1 FileS 2006 01 01 – 2006 01 29 SerieS 2.0 ManuScriptS and draftS……………………………………………………………2 Sub-SerieS 2.1. NovelS Sub-SerieS 2.2. Short StorieS Sub-SerieS 2.3. Poetry Sub-SerieS 2.4. Non-fiction SerieS 3.0 General correSpondence…………………………………………………………..3 Sub-SerieS 3.1. Outgoing correSpondence Sub-SerieS 3.2. Incoming correSpondence SerieS 4.0 PubliShing records and buSineSS correSpondence………………………………….4 SerieS 5.0 ProfeSSional activitieS materialS……………………………………………………5 Sub-SerieS 5.1. Editorial, collaborative and contributive materialS Sub-SerieS 5.2. Canada Council paperS Sub-SerieS 5.3. Public readingS, interviewS and conference material SerieS 6.0 Student material…………………………………………………………………...6 SerieS 7.0 Teaching material………………………………………………………………….7 Sub-SerieS 7.1. Elementary and secondary school teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.2. UniverSity of BritiSh Columbia teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.3. UniverSity of Toronto teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.4. UniverSity of Alberta teaching material Sub-SerieS 7.5. PoSt-retirement teaching material SerieS 8.0 Research and reference materialS…………………………………………………..8 Sub-serieS 8.1. -

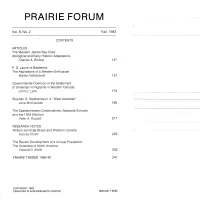

PF Vol. 08 No.02.Pdf (13.31Mb)

PRAIRIE FORUM Vol. 8, NO.2 Fall, 1983 CONTENTS ARTICLES The Western James Bay Cree: Aboriginal and Early Historic Adaptations Charles A. Bishop 147 P. G. Laurie of Battleford: The Aspirations of a Western Enthusiast Walter Hildebrandt . 157 Governmental Coercion in the Settlement of Ukrainian Immigrants in Western Canada John C. Lehr 179 Stephan G. Stephansson: A "West Icelander" Jane McCracken 195 The Saskatchewan Conservatives, Separate Schools and the 1929 Election Peter A. Russell 211 RESEARCH NOTES William Jenninqs Bryan and Western Canada Harvey Strum 225 The Recent Development of a Unique Population: The Hutterites of North America Edward D. Boldt 235 PRAIRIE THESES, 1980-81 241 COPYRIGHT 1983 CANADIAN PLAINS RESEARCH CENTER ISSN 0317 -6282 BOOK REVIEWS DEN OTTER, A. A., Civilizing the West: The GaIts and the Development of Western Canada by Michael J. Carley 251 DEN OTTER, A. A., Civilizing the West: The GaIts and the Development of Western Canada _ by Carl Betke .................................................. .. 252 FOSTER, JOHN (editor), The Developing West, Essays on Canadian History in Honour of L. H. Thomas by Donald B. Wetherell. ......................................... .. 254 MACDONALD, E. A., The Rainbow Chasers by Simon Evans 258 KERR, D., A New Improved Sky by William Latta 260 KERR, D. C. (editor), Western Canadian Politics: The Radical Tradition by G. A. Rawlyk 263 McCRACKEN, JANE, Stephan G. Stephansson: The Poet of the Rocky Mountains by Brian Evans. ................................................ .. 264 SUMMERS, MERNA, Calling Home by R. T. Robertson 266 MALCOLM, M. J., Murder in the Yukon: The Case Against George O'Brien by Thomas Thorner 268 KEITH, W. J., Epic Fiction: The Art of Rudy Wiebe by Don Murray 270 STOWE, L., The Last Great Frontiersman: The Remarkable Adventures of Tom Lamb by J. -

9. the Mythological and the Real

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2017-05 Writing Alberta: Building on a Literary Identity Melnyk, George; Coates, Donna University of Calgary Press http://hdl.handle.net/1880/52097 book Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca WRITING ALBERTA: Aberta Building on a Literary Identity Edited by George Melnyk and Donna Coates ISBN 978-1-55238-891-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Canadianliterature

Canadian Literature/ Littératurecanadienne A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Number 195, Winter 2007, Context(e)s Published by The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Editor: Margery Fee Associate Editors: Laura Moss (Reviews), Glenn Deer (Reviews), Larissa Lai (Poetry), Réjean Beaudoin (Francophone Writing), Judy Brown (Reviews) Past Editors: George Woodcock (1959–1977), W.H. New (1977–1995), Eva-Marie Kröller (1995–2003), Laurie Ricou (2003–2007) Editorial Board Heinz Antor Universität Köln Janice Fiamengo University of Ottawa Carole Gerson Simon Fraser University Coral Ann Howells University of Reading Smaro Kamboureli University of Guelph Jon Kertzer University of Calgary Ric Knowles University of Guelph Neil ten Kortenaar University of Toronto Louise Ladouceur University of Alberta Patricia Merivale University of British Columbia Judit Molnár University of Debrecen Leslie Monkman Queen’s University Maureen Moynagh St. Francis Xavier University Élizabeth Nardout-Lafarge Université de Montréal Ian Rae McGill University Roxanne Rimstead Université de Sherbrooke Patricia Smart Carleton University David Staines University of Ottawa Penny van Toorn University of Sydney David Williams University of Manitoba Mark Williams University of Canterbury Editorial Margery Fee Réjean Beaudoin Context(e)s 6 Articles Cheryl Lousley Knowledge, Power and Place: Environmental Politics in the Fiction of Matt Cohen and David Adams Richards 11 Martine-Emmanuelle Lapointe Réjean Ducharme, le tiers inclus : Relecture de L’avalée des avalés 32 Jean-Sébastien Ménard Sur la langue de Kerouac 50 David Décarie Le secret de Manouche : Le thème de la fille-mère dans le Cycle du Survenant de Germaine Guèvremont 68 Articles, continued Colin Hill Canadian Bookman and the Origins of Modern Realism in English-Canadian Fiction 85 Lisa M. -

Proquest Dissertations

The Double Hook By Sheila Watson Edited with Introduction and Notes By Alicia Fahey A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario © Copyright (Introduction and Notes) by Alicia Fahey, 2011 English (Public Texts) M.A. Graduate Program September 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-81127-6 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-81127-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extra its substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Sheila Watson's Life and Writing

WRITING ALBERTA: Aberta Building on a Literary Identity Edited by George Melnyk and Donna Coates ISBN 978-1-55238-891-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. If you want to reuse or distribute the work, you must inform its new audience of the licence terms of this work.