Corticotropin Releasing Hormone Receptor CRHR1 Gene Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Involvement of Catecholaminergic and Gabaaergic Mediations in the Anxiety-Related Behavior in Long-Term Powdered Diet-Fed Mice T

Neurochemistry International 124 (2019) 1–9 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neurochemistry International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/neuint Involvement of catecholaminergic and GABAAergic mediations in the anxiety-related behavior in long-term powdered diet-fed mice T ∗ Fukie Yaoitaa, , Masahiro Tsuchiyab, Yuichiro Araic, Takeshi Tadanod, Koichi Tan-Noa a Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tohoku Medical and Pharmaceutical University, 4-4-1 Komatsushima, Aoba-ku, Sendai, 981-8558, Japan b Department of Nursing, Tohoku Fukushi University, 1-8-1 Kunimi, Aoba-ku, Sendai, 981-8522, Japan c Tokyo Ariake University of Medical and Health Science, 2-9-1 Ariake, Koto-Ku, Tokyo, 135-0063, Japan d Complementary and Alternative Medicine Clinical Research and Development, Graduate School of Medicine Sciences, Kanazawa University, Kakumamachi, Kanazawa, 920-1192, Japan ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Dietary habits are important factors which affect metabolic homeostasis and the development of emotion. We Atomoxetine have previously shown that long-term powdered diet feeding in mice increases spontaneous locomotor activity Methylphenidate and social interaction (SI) time. Moreover, that diet causes changes in the dopaminergic system, especially PD168077 increased dopamine turnover and decreased dopamine D4 receptor signals in the frontal cortex. Although the Anxiety-related behavior increased SI time indicates low anxiety, the elevated plus maze (EPM) test shows anxiety-related behavior and Low anxiety impulsive behavior. In this study, we investigated whether the powdered diet feeding causes changes in anxiety- Bicuculline Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder related behavior. Mice fed a powdered diet for 17 weeks from weaning were compared with mice fed a standard diet (control). -

Auckland Uniservices Limited

Auckland UniServices Limited Legally available, unclassified psychoactive substances and illegal drugs in New Zealand before and after the ban on BZP: a web‐ based survey of patterns of use FINAL REPORT OF FINDINGS June 2009 Janie Sheridan, PhD, BPharm, BA, FRPharmS, RegPharmNZ Rachael Butler, BA, PGDipPH Christine Y. Dong, BSc Hons, BCom Hons Joanne Barnes, PhD, BPharm, MRPharmS, RegPharmNZ, FLS The School of Pharmacy The University of Auckland New Zealand TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 7 2 Introduction .................................................................................................... 11 2.1 Background .............................................................................................. 11 2.1.1 The legislative and regulatory background ................................ 11 2.1.2 The current study ........................................................................ 12 2.2 Study aims ................................................................................................ 12 2.3 Study methods ......................................................................................... 13 2.4 Ethics approval ......................................................................................... 13 2.5 Structure of this report ............................................................................ 13 3 Adverse effects associated with herbal substances used for recreational purposes: a literature review -

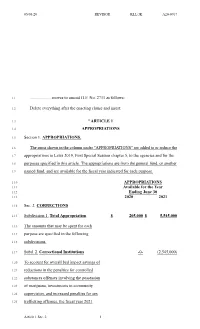

Moves to Amend HF No. 2711 As Follows

05/05/20 REVISOR KLL/JK A20-0767 1.1 .................... moves to amend H.F. No. 2711 as follows: 1.2 Delete everything after the enacting clause and insert: 1.3 "ARTICLE 1 1.4 APPROPRIATIONS 1.5 Section 1. APPROPRIATIONS. 1.6 The sums shown in the column under "APPROPRIATIONS" are added to or reduce the 1.7 appropriations in Laws 2019, First Special Session chapter 5, to the agencies and for the 1.8 purposes specified in this article. The appropriations are from the general fund, or another 1.9 named fund, and are available for the fiscal year indicated for each purpose. 1.10 APPROPRIATIONS 1.11 Available for the Year 1.12 Ending June 30 1.13 2020 2021 1.14 Sec. 2. CORRECTIONS 1.15 Subdivision 1. Total Appropriation $ 205,000 $ 5,545,000 1.16 The amounts that may be spent for each 1.17 purpose are specified in the following 1.18 subdivisions. 1.19 Subd. 2. Correctional Institutions -0- (2,545,000) 1.20 To account for overall bed impact savings of 1.21 reductions in the penalties for controlled 1.22 substances offenses involving the possession 1.23 of marijuana, investments in community 1.24 supervision, and increased penalties for sex 1.25 trafficking offenses, the fiscal year 2021 Article 1 Sec. 2. 1 05/05/20 REVISOR KLL/JK A20-0767 2.1 appropriation from Laws 2019, First Special 2.2 Session chapter 5, article 1, section 15, 2.3 subdivision 2, is reduced by $2,545,000. 2.4 Subd. -

Neuroenhancement in Healthy Adults, Part I: Pharmaceutical

l Rese ca arc ni h li & C f B o i o l e Journal of a t h n Fond et al., J Clinic Res Bioeth 2015, 6:2 r i c u s o J DOI: 10.4172/2155-9627.1000213 ISSN: 2155-9627 Clinical Research & Bioethics Review Article Open Access Neuroenhancement in Healthy Adults, Part I: Pharmaceutical Cognitive Enhancement: A Systematic Review Fond G1,2*, Micoulaud-Franchi JA3, Macgregor A2, Richieri R3,4, Miot S5,6, Lopez R2, Abbar M7, Lancon C3 and Repantis D8 1Université Paris Est-Créteil, Psychiatry and Addiction Pole University Hospitals Henri Mondor, Inserm U955, Eq 15 Psychiatric Genetics, DHU Pe-psy, FondaMental Foundation, Scientific Cooperation Foundation Mental Health, National Network of Schizophrenia Expert Centers, F-94000, France 2Inserm 1061, University Psychiatry Service, University of Montpellier 1, CHU Montpellier F-34000, France 3POLE Academic Psychiatry, CHU Sainte-Marguerite, F-13274 Marseille, Cedex 09, France 4 Public Health Laboratory, Faculty of Medicine, EA 3279, F-13385 Marseille, Cedex 05, France 5Inserm U1061, Idiopathic Hypersomnia Narcolepsy National Reference Centre, Unit of sleep disorders, University of Montpellier 1, CHU Montpellier F-34000, Paris, France 6Inserm U952, CNRS UMR 7224, Pierre and Marie Curie University, F-75000, Paris, France 7CHU Carémeau, University of Nîmes, Nîmes, F-31000, France 8Department of Psychiatry, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Campus Benjamin Franklin, Eschenallee 3, 14050 Berlin, Germany *Corresponding author: Dr. Guillaume Fond, Pole de Psychiatrie, Hôpital A. Chenevier, 40 rue de Mesly, Créteil F-94010, France, Tel: (33)178682372; Fax: (33)178682381; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: January 06, 2015, Accepted date: February 23, 2015, Published date: February 28, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Fond G, et al. -

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Cr

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Crizotinib (PF-02341066) 1 4 55 Docetaxel 1 5 98 Anastrozole 1 6 25 Cladribine 1 7 23 Methotrexate 1 8 -187 Letrozole 1 9 65 Entecavir Hydrate 1 10 48 Roxadustat (FG-4592) 1 11 19 Imatinib Mesylate (STI571) 1 12 0 Sunitinib Malate 1 13 34 Vismodegib (GDC-0449) 1 14 64 Paclitaxel 1 15 89 Aprepitant 1 16 94 Decitabine 1 17 -79 Bendamustine HCl 1 18 19 Temozolomide 1 19 -111 Nepafenac 1 20 24 Nintedanib (BIBF 1120) 1 21 -43 Lapatinib (GW-572016) Ditosylate 1 22 88 Temsirolimus (CCI-779, NSC 683864) 1 23 96 Belinostat (PXD101) 1 24 46 Capecitabine 1 25 19 Bicalutamide 1 26 83 Dutasteride 1 27 68 Epirubicin HCl 1 28 -59 Tamoxifen 1 29 30 Rufinamide 1 30 96 Afatinib (BIBW2992) 1 31 -54 Lenalidomide (CC-5013) 1 32 19 Vorinostat (SAHA, MK0683) 1 33 38 Rucaparib (AG-014699,PF-01367338) phosphate1 34 14 Lenvatinib (E7080) 1 35 80 Fulvestrant 1 36 76 Melatonin 1 37 15 Etoposide 1 38 -69 Vincristine sulfate 1 39 61 Posaconazole 1 40 97 Bortezomib (PS-341) 1 41 71 Panobinostat (LBH589) 1 42 41 Entinostat (MS-275) 1 43 26 Cabozantinib (XL184, BMS-907351) 1 44 79 Valproic acid sodium salt (Sodium valproate) 1 45 7 Raltitrexed 1 46 39 Bisoprolol fumarate 1 47 -23 Raloxifene HCl 1 48 97 Agomelatine 1 49 35 Prasugrel 1 50 -24 Bosutinib (SKI-606) 1 51 85 Nilotinib (AMN-107) 1 52 99 Enzastaurin (LY317615) 1 53 -12 Everolimus (RAD001) 1 54 94 Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) 1 55 24 Thalidomide 1 56 40 Tivozanib (AV-951) 1 57 86 Fludarabine -

ANTIDEPRESSANTS in USE in CLINICAL PRACTICE Mark Agius1 & Hannah Bonnici2 1Clare College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 2Hospital Pharmacy St

Psychiatria Danubina, 2017; Vol. 29, Suppl. 3, pp 667-671 Conference paper © Medicinska naklada - Zagreb, Croatia ANTIDEPRESSANTS IN USE IN CLINICAL PRACTICE Mark Agius1 & Hannah Bonnici2 1Clare College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK 2Hospital Pharmacy St. James Hospital Malta, Malta SUMMARY The object of this paper, rather than producing new information, is to produce a useful vademecum for doctors prescribing antidepressants, with the information useful for their being prescribed. Antidepressants need to be seen as part of a package of treatment for the patient with depression which also includes psychological treatments and social interventions. Here the main Antidepressant groups, including the Selective Serotonin uptake inhibiters, the tricyclics and other classes are described, together with their mode of action, side effects, dosages. Usually antidepressants should be prescribed for six months to treat a patient with depression. The efficacy of anti-depressants is similar between classes, despite their different mechanisms of action. The choice is therefore based on the side-effects to be avoided. There is no one ideal drug capable of exerting its therapeutic effects without any adverse effects. Increasing knowledge of what exactly causes depression will enable researchers not only to create more effective antidepressants rationally but also to understand the limitations of existing drugs. Key words: antidepressants – depression - psychological therapies - social therapies * * * * * Introduction Monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors í Non-selective Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors Depression may be defined as a mood disorder that í Selective Monoamine Oxidase Type A inhibitors negatively and persistently affects the way a person feels, thinks and acts. Common signs include low mood, Atypical Anti-Depressants and other classes changes in appetite and sleep patterns and loss of inte- rest in activities that were once enjoyable. -

Molecular Profile of Dissociative Drug Ketamine in Relation to Its Rapid Antidepressant Action

Ficek et al. BMC Genomics (2016) 17:362 DOI 10.1186/s12864-016-2713-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Molecular profile of dissociative drug ketamine in relation to its rapid antidepressant action Joanna Ficek, Magdalena Zygmunt, Marcin Piechota, Dzesika Hoinkis, Jan Rodriguez Parkitna, Ryszard Przewlocki and Michal Korostynski* Abstract Background: The NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine was found to act as a fast-acting antidepressant. The effects of single treatment were reported to persist for days to weeks, even in otherwise treatment-refractory cases. Identification of the mechanisms underlying ketamine’s antidepressant action may permit development of novel drugs, with similar clinical properties but lacking psychotomimetic, sedative and other side effects. Methods: We applied whole-genome microarray profiling to analyze detailed time-course (1, 2, 4 and 8 h) of transcriptome alterations in the striatum and hippocampus following acute administration of ketamine, memantine and phencyclidine in C57BL/6 J mice. The transcriptional effects of ketamine were further analyzed using next-generation sequencing and quantitative PCR. Gene expression alterations induced by the NMDA antagonists were compared to the molecular profiles of psychotropic drugs: antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, psychostimulants and opioids. Results: We identified 52 transcripts (e.g. Dusp1, Per1 and Fkbp5) with altered expression (FDR < 1 %) in response to treatment with NMDA receptor antagonists. Functional links that connect expression of the regulated genes to the MAPK, IL-6 and insulin signaling pathways were indicated. Moreover, ketamine-regulated expression of specific gene isoforms was detected (e.g. Tsc22d3, Sgk1 and Hif3a). The comparison with other psychotropic drugs revealed that the molecular effects of ketamine are most similar to memantine and phencyclidine. -

Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Second Generation

Forensic Screening of 300 Drugs in Blood Utilizing Exactive Plus High-Resolution Accurate Mass Spectrometer and ExactFinder Software Kristine Van Natta, Marta Kozak, Xiang He Forensic Toxicology use Only Drugs analyzed Compound Compound Compound Atazanavir Efavirenz Pyrilamine Chlorpropamide Haloperidol Tolbutamide 1-(3-Chlorophenyl)piperazine Des(2-hydroxyethyl)opipramol Pentazocine Atenolol EMDP Quinidine Chlorprothixene Hydrocodone Tramadol 10-hydroxycarbazepine Desalkylflurazepam Perimetazine Atropine Ephedrine Quinine Cilazapril Hydromorphone Trazodone 5-(p-Methylphenyl)-5-phenylhydantoin Desipramine Phenacetin Benperidol Escitalopram Quinupramine Cinchonine Hydroquinine Triazolam 6-Acetylcodeine Desmethylcitalopram Phenazone Benzoylecgonine Esmolol Ranitidine Cinnarizine Hydroxychloroquine Trifluoperazine Bepridil Estazolam Reserpine 6-Monoacetylmorphine Desmethylcitalopram Phencyclidine Cisapride HydroxyItraconazole Trifluperidol Betaxolol Ethyl Loflazepate Risperidone 7(2,3dihydroxypropyl)Theophylline Desmethylclozapine Phenylbutazone Clenbuterol Hydroxyzine Triflupromazine Bezafibrate Ethylamphetamine Ritonavir 7-Aminoclonazepam Desmethyldoxepin Pholcodine Clobazam Ibogaine Trihexyphenidyl Biperiden Etifoxine Ropivacaine 7-Aminoflunitrazepam Desmethylmirtazapine Pimozide Clofibrate Imatinib Trimeprazine Bisoprolol Etodolac Rufinamide 9-hydroxy-risperidone Desmethylnefopam Pindolol Clomethiazole Imipramine Trimetazidine Bromazepam Felbamate Secobarbital Clomipramine Indalpine Trimethoprim Acepromazine Desmethyltramadol Pipamperone -

Site Selective C–H Functionalization of Mitragyna Alkaloids Reveals A

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23736-2 OPEN Site selective C–H functionalization of Mitragyna alkaloids reveals a molecular switch for tuning opioid receptor signaling efficacy Srijita Bhowmik 1,12, Juraj Galeta 1,2,12, Václav Havel 1, Melissa Nelson 3,4, Abdelfattah Faouzi 5,6, Benjamin Bechand1, Mike Ansonoff 7, Tomas Fiala 1,8, Amanda Hunkele5,9, Andrew C. Kruegel1, ✉ John. E. Pintar 7, Susruta Majumdar 5, Jonathan A. Javitch 3,4 & Dalibor Sames 1,10,11 1234567890():,; Mitragynine (MG) is the most abundant alkaloid component of the psychoactive plant material “kratom”, which according to numerous anecdotal reports shows efficacy in self-medication for pain syndromes, depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders. We have developed a synthetic method for selective functionalization of the unexplored C11 position of the MG scaffold (C6 position in indole numbering) via the use of an indole-ethylene glycol adduct and subsequent iridium-catalyzed borylation. Through this work we discover that C11 represents a key locant for fine-tuning opioid receptor signaling efficacy. 7-Hydroxymitragynine (7OH), the parent compound with low efficacy on par with buprenorphine, is transformed to an even lower efficacy agonist by introducing a fluorine substituent in this position (11-F-7OH), as demonstrated in vitro at both mouse and human mu opioid receptors (mMOR/hMOR) and in vivo in mouse analgesia tests. Low efficacy opioid agonists are of high interest as candidates for generating safer opioid medications with mitigated adverse effects. 1 Department of Chemistry, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. 2 Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Czech Academy of Sciences (IOCB Prague), 160 00 Prague 6, Czech Republic. -

In Vivo Electrophysiological Recordings of the Effects of Antidepressant Drugs

Experimental Brain Research (2019) 237:1593–1614 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-019-05556-5 REVIEW In vivo electrophysiological recordings of the efects of antidepressant drugs Paul J. Fitzgerald1 · Brendon O. Watson1 Received: 9 October 2018 / Accepted: 6 May 2019 / Published online: 11 May 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract Antidepressant drugs are a standard biological treatment for various neuropsychiatric disorders, yet relatively little is known about their electrophysiologic and synaptic efects on mood systems that set moment-to-moment emotional tone. In vivo electrical recording of local feld potentials (LFPs) and single neuron spiking has been crucial for elucidating important details of neural processing and control in many other systems, and yet electrical approaches have not been broadly applied to the actions of antidepressants on mood-related circuits. Here we review the literature encompassing electrophysiologic efects of antidepressants in animals, including studies that examine older drugs, and extending to more recently synthesized novel compounds, as well as rapidly acting antidepressants. The existing studies on neuromodulator-based drugs have focused on recording in the brainstem nuclei, with much less known about their efects on prefrontal or sensory cortex. Studies on neuromodulatory drugs have moreover focused on single unit fring patterns with less emphasis on LFPs, whereas the rapidly acting antidepressant literature shows the opposite trend. In a synthesis of this information, we hypothesize that all classes of antidepressants could have common fnal efects on limbic circuitry. Whereas NMDA receptor blockade may induce a high powered gamma oscillatory state via direct and fast alteration of glutamatergic systems in mood-related circuits, neuromodulatory antidepressants may induce similar efects over slower timescales, corresponding with the timecourse of response in patients, while resetting synaptic excitatory versus inhibitory signaling to a normal level. -

Discovering Alternative Treatments for Opioid Use Recovery Using Social Media

CHI 2019 Paper CHI 2019, May 4–9, 2019, Glasgow, Scotland, UK Discovering Alternative Treatments for Opioid Use Recovery Using Social Media Stevie Chancellor George Nitzburg Andrea Hu Georgia Tech Teachers College Georgia Tech Atlanta, GA, US Columbia University Atlanta, GA, US [email protected] New York, NY, US [email protected] [email protected] Francisco Zampieri Munmun De Choudhury Georgia Tech Georgia Tech Atlanta, GA, US Atlanta, GA, US [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Opioid use disorder (OUD) poses substantial risks to per- opioid use disorder; recovery; Reddit; alternative treatment; sonal well-being and public health. In online communities, addiction; online communities users support those seeking recovery, in part by promoting ACM Reference Format: clinically grounded treatments. However, some communi- Stevie Chancellor, George Nitzburg, Andrea Hu, Francisco Zampieri, ties also promote clinically unverified OUD treatments, such and Munmun De Choudhury. 2019. Discovering Alternative Treat- as unregulated and untested drugs. Little research exists on ments for Opioid Use Recovery Using Social Media. In CHI Con- which alternative treatments people use, whether these treat- ference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Proceedings (CHI ments are effective for recovery, or if they cause negative 2019), May 4–9, 2019, Glasgow, Scotland UK. ACM, New York, NY, side effects. We provide the first large-scale social media USA, 15 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300354 study of clinically unverified, alternative treatments in OUD recovery on Reddit, partnering with an addiction research 1 INTRODUCTION scientist. We adopt transfer learning across 63 subreddits to Opioid use disorder (OUD)1 is one of the most pressing public precisely identify posts related to opioid recovery. -

Agomelatine and Tianeptine Antidepressant Activity in Mice Behavioral

Pharmacological Reports 71 (2019) 676–681 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Pharmacological Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pharep Short communication Agomelatine and tianeptine antidepressant activity in mice behavioral despair tests is enhanced by DMPX, a selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist, but not DPCPX, a selective adenosine A1 receptor antagonist a, a a b a _ Aleksandra Szopa *, Karolina Bogatko , Anna Serefko , Elzbieta Wyska , Sylwia Wosko , a c d e Katarzyna Swia˛der , Urszula Doboszewska , Aleksandra Wlaz , Andrzej Wróbel , c f a Piotr Wlaz , Jarosław Dudka , Ewa Poleszak a Department of Applied Pharmacy, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland b Department of Pharmacokinetics and Physical Pharmacy, Collegium Medicum, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland c Department of Animal Physiology, Institute of Biology and Biochemistry, Faculty of Biology and Biotechnology, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland d Department of Pathophysiology, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland e Second Department of Gynecology, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland f Chair and Department of Toxicology, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Background: Adenosine, an endogenous nucleoside, modulates the release of monoamines, e.g., Received 9 October 2018 noradrenaline, serotonin, and dopamine in the brain. Both nonselective and selective stimulation of Received in revised form 12 February 2019 adenosine receptors produce symptoms of depression in some animal models. Therefore, the main Accepted 11 March 2019 objective of our study was to assess the influence of a selective adenosine A1 receptor antagonist (DPCPX) Available online 16 March 2019 and a selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist (DMPX) on the activity of agomelatine and tianeptine.