Operating Systems Engineering Xv6 & Page Tables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CS 4414 — Introduction

CS 4414 — introduction 1 Changelog Changes made in this version not seen in first lecture: 27 Aug 2019: remove mention of department login server being alternative for xv6, though it may be useful for other assignments 1 course webpage https://www.cs.virginia.edu/~cr4bd/4414/F2019/ linked off Collab 2 homeworks there will be programming assignments …mostly in C or C++ possibly one assignment in Python one or two weeks if two weeks “checkpoint” submission after first week two week assignments worth more schedule is aggressive… 3 xv6 some assignments will use xv6, a teaching operating system simplified OS based on an old Unix version built by some people at MIT theoretically actually boots on real 32-bit x86 hardware …and supports multicore! (but we’ll run it only single-core, in an emulator) 4 quizzes there will be online quizzes after each week of lecture …starting this week (due next Tuesday) same interface as CS 3330, but no time limit (haven’t seen it? we’ll talk more on Thursday) quizzes are open notes, open book, open Internet 5 exams midterm and final let us know soon if you can’t make the midterm 6 textbook recommended textbook: Operating Systems: Principles and Practice no required textbook alternative: Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces (free PDFs!) some topics we’ll cover where this may be primary textbook alternative: Silberchartz (used in previous semesters) full version: Operating System Concepts, Ninth Edition 7 cheating: homeworks don’t homeworks are individual no code from prior semesters no sharing code, pesudocode, detailed descriptions of code no code from Internet/etc., with limited exceptions tiny things solving problems that aren’t point of assignment …credited where used in your code e.g. -

W4118 Operating Systems Logistics

W4118 Operating Systems I Junfeng Yang References: Modern Operating Systems (3rd edition), Operating Systems Concepts (8th edition), previous W4118, and OS at MIT, Stanford, and UWisc Bad News This is a TOUGH course . “Most difficult” rated by CS alumni Unfamiliar low-level systems programming . C and Assembly . No abstraction, close to hardware Intense . “Should be 6 units instead of 3” … . Most of those struggling in CS lounge or CLIC lab late or possibly overnight were OS students And you have to climb up N floors for lecture! . Or wait 10 minutes for elevator … Good News Not interested in learning OS or low-level systems programming? Don’t have to take this course! . New MS Breadth requirement . Waive if you have taken a similar course More Good News Heavy, but totally worth it . “Most useful after graduating” rated by alumni Works hard good grade We’ll do our best to help you Climbing up N floors is good exercise! Why Study OS? OS = arguably the most fundamental software . We do almost everything with computers through OS By studying OS, you will . Gain a good understanding of OS . Gain a good understanding of the big picture • How do hardware, programming language, compiler, algorithms, OS work together? . Learn some portable tricks Possibly . Land a job at Facebook/Google/Microsoft/VMware/… . Get started in systems research . Apply OS ideas to your research area . … What Will We Learn? OS concepts . What does an OS do? • Abstract hardware: processes, threads, files • Manage resources: CPU scheduling, memory management, file systems OS implementation techniques . How does an OS implement X in general? . -

Network Driver for Micro Os Xv6

NETWORK DRIVER FOR MICRO OS XV6 A Project Presented to the faculty of the Department of Computer Science California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Computer Science by Anmoldeep Singh Sandhu SPRING 2020 © 2020 Anmoldeep Singh Sandhu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii NETWORK DRIVER FOR MICRO OS XV6 A Project by Anmoldeep Singh Sandhu Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Jinsong Ouyang __________________________________, Second Reader Dr. Jingwei Yang ____________________________ Date iii Student: Anmoldeep Singh Sandhu I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and this thesis is suitable for electronic submission to the library. Credit is awarded for the Project. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator ___________________ Dr. Jinsong Ouyang Date Department of Computer Science iv Abstract of NETWORK DRIVER FOR MICRO OS XV6 by Anmoldeep Singh Sandhu The network driver is one of the primary requirements for any operating system. Xv6 is a micro-operating system based on version 6 Unix. The latest version of xv6 does not have support for the ethernet driver or the four-layer UDP/IP model. Our work extends the xv6 operating system to support a functioning network driver with the capability of handling a packet burst. This Project also adds support for UDP/IP and Ethernet protocol to the xv6 operating system. _______________________ Committee Chair Dr. Jinsong Ouyang _____________________ Date v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am thankful to Dr. Ouyang for providing me the opportunity to learn new skills in the field of driver development. Dr. Ouyang showed trust in me in carrying out this Project. -

Operating Systems – Assignment 1 Xv6, Processes, System Calls and Scheduling

OPERATING SYSTEMS – ASSIGNMENT 1 XV6, PROCESSES, SYSTEM CALLS AND SCHEDULING Introduction Throughout this course we will be using a simple, UNIX like teaching operating system called xv6: http://pdos.csail.mit.edu/6.828/2010/xv6-book/index.html The xv6 OS is simple enough to cover and understand within a few weeks yet it still contains the important concepts and organizational structure of UNIX. To run it, you will have to compile the source files and use the QEMU processor emulator (installed on all CS lab computers). Tip: xv6 was (and still is) developed as part of MIT’s 6.828 Operating Systems Engineering course. You can find a lot of useful information and getting started tips there: http://pdos.csail.mit.edu/6.828/2010/overview.html Tip: xv6 has a very useful guide. It will greatly assist you throughout the course assignments: http://pdos.csail.mit.edu/6.828/2011/xv6/book-rev6.pdf Tip: you may also find the following useful: http://pdos.csail.mit.edu/6.828/2011/xv6/xv6-rev6.pdf In this assignment we will start exploring xv6 and extend it to support various scheduling policies. Task 0: Running xv6 Begin by downloading our revision of xv6, from the OS132 svn repository: Open a shell, and traverse to a directory in your computer where you want to store the sources for the OS course. For example, in Linux: mkdir ~/os132 cd ~/os132 Execute the following command (in a single line): svn checkout http://bgu-os-132-xv6.googlecode.com/svn/trunk assignment1 This will create a new folder called assignment1 which will contain all project files. -

Porting the Embedded Xinu Operating System to the Raspberry Pi Eric Biggers Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science Honors Projects 5-2014 Porting the Embedded Xinu Operating System to the Raspberry Pi Eric Biggers Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/mathcs_honors Part of the OS and Networks Commons, Software Engineering Commons, and the Systems Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Biggers, Eric, "Porting the Embedded Xinu Operating System to the Raspberry Pi" (2014). Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science Honors Projects. 32. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/mathcs_honors/32 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics, Statistics, and Computer Science Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MACALESTER COLLEGE HONORS PAPER IN COMPUTER SCIENCE Porting the Embedded Xinu Operating System to the Raspberry Pi Author: Advisor: Eric Biggers Shilad Sen May 5, 2014 Abstract This thesis presents a port of a lightweight instructional operating system called Em- bedded Xinu to the Raspberry Pi. The Raspberry Pi, an inexpensive credit-card-sized computer, has attracted a large community of hobbyists, researchers, and educators since its release in 2012. However, the system-level software running on the Raspberry Pi has been restricted to two ends of a spectrum: complex modern operating systems such as Linux at one end, and very simple hobbyist operating systems or simple “bare-metal” programs at the other end. -

Adding a System Call to Xv6 1 Overview 2 Part 1: Xv6 on QEMU

COP4610: Introduction to Operating Systems Project 1: Adding a System Call to xv6 1 Overview In this assignment, you will get to know xv6, a simple Unix-like teaching operating system from MIT. You’ll do three things in this assignment: • You’ll get xv6 to run on a system emulator, QEMU; relax, this is a pretty quick and painless process. • You’ll trace the open() system call of xv6 and document what goes on at each step. • You’ll implement the ps program which displays the list of processes currently in the system; for this to work, you’ll have to carefully introduce a new system call. Words of Wisdom: First, please start early! Second, please make minimal changes to xv6; you do not want to make it hard for us to grade! 2 Part 1: xv6 on QEMU (20%) The first part is easy. You need to download xv6, compile it and make a disk image, and get that disk image to run on QEMU. Grabbing the xv6 source here (MD5 Checksum: 729d72a29f64673a5ddb51f7174a03fa). Extract the sources, then take a quick look around. Compiling xv6 should work fine by just saying make in the xv6 directory. You’ll see a lot of lines fly by, and eventually you’ll have an image file xv6.img. Running xv6 on QEMU should work fine by just saying make qemu in the xv6 directory. And there you have it. Try running ls and mkdir and friends. You can even run sh to get a new shell process (use CTRL-D to leave it as there’s no exit command). -

Synchronization in Xv6

Lectures on Operating Systems (Mythili Vutukuru, IIT Bombay) Practice Problems: Synchronization in xv6 1. Modern operating systems disable interrupts on specific cores when they need to turn off preemp- tion, e.g., when holding a spin lock. For example, in xv6, interrupts can be disabled by a function call cli(), and reenabled with a function call sti(). However, functions that need to disable and enable interrupts do not directly call the cli() and sti() functions. Instead, the xv6 ker- nel disables interrupts (e.g., while acquiring a spin lock) by calling the function pushcli(). This function calls cli(), but also maintains of count of how many push calls have been made so far. Code that wishes to enable interrupts (e.g., when releasing a spin lock) calls popcli(). This function decrements the above push count, and enables interrupts using sti() only after the count has reached zero. That is, it would take two calls to popcli() to undo the effect of two pushcli() calls and restore interrupts. Provide one reason why modern operating systems use this method to disable/enable interrupts, instead of directly calling the cli() and sti() func- tions. In other words, explain what would go wrong if every call to pushcli() and popcli() in xv6 were to be replaced by calls to cli() and sti() respectively. Ans: If one acquires multiple spinlocks (say, while serving nested interrupts, or for some other reason), interrupts should be enabled only after locks have been released. Therefore, the push and pop operations capture how many times interrupts have been disabled, so that interrupts can be reenabled only after all such operations have been completed. -

Multi-Persona Mobile Computing

Multi-Persona Mobile Computing Jeremy Andrus Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 c 2015 Jeremy Andrus All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Multi-Persona Mobile Computing Jeremy Andrus Smartphones and tablets are increasingly ubiquitous, and many users rely on multiple mobile devices to accommodate work, personal, and geographic mobility needs. Pervasive access to always-on mobile com- puting has created new security and privacy concerns for mobile devices that often force users to carry multiple devices to meet those needs. The volume and popularity of mobile devices has commingled hard- ware and software design, and created tightly vertically integrated platforms that lock users into a single, vendor-controlled ecosystem. My thesis is that lightweight mechanisms can be added to commodity operat- ing systems to enable multiple virtual phones or tablets to run at the same time on a physical smartphone or tablet device, and to enable apps from multiple mobile platforms, such as iOS and Android, to run together on the same physical device, all while maintaining the low-latency and responsiveness expected of modern mobile devices. This dissertation presents two lightweight operating systems mechanisms, virtualization and binary compatibility, that enable multi-persona mobile computing. First, we present Cells, a mobile virtualization architecture enabling multiple virtual phones, or personas, to run simultaneously on the same physical cellphone in a secure and isolated manner. Cells introduces device namespaces that allow apps to run in a virtualized environment while still leveraging native devices such as GPUs to provide accelerated graphics. -

I/O Devices General I/O Bus (E.G., PCI)

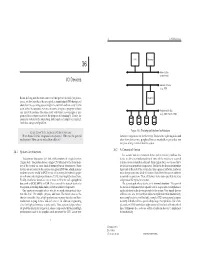

2 I/O D EVICES CPU Memory 36 Memory Bus (proprietary) I/O Devices General I/O Bus (e.g., PCI) Before delving into the main content of this part of the book (on persis- Graphics tence), we first introduce the concept of an input/output (I/O) device and show how the operating system might interact with such an entity. I/O is quite critical to computer systems, of course; imagine a program without Peripheral I/O Bus any input (it produces the same result each time); now imagine a pro- (e.g., SCSI, SATA, USB) gram with no output (what was the purpose of it running?). Clearly, for computer systems to be interesting, both input and output are required. And thus, our general problem: Figure 36.1: Prototypical System Architecture CRUX : H OW TO INTEGRATE I/O I NTO SYSTEMS How should I/O be integrated into systems? What are the general formance components are further away. The benefits of placing disks and mechanisms? How can we make them efficient? other slow devices on a peripheral bus are manifold; in particular, you can place a large number of devices on it. 36.2 A Canonical Device 36.1 System Architecture Let us now look at a canonical device (not a real one), and use this To begin our discussion, let’s look at the structure of a typical system device to drive our understanding of some of the machinery required (Figure 36.1). The picture shows a single CPU attached to the main mem- to make device interaction efficient. -

CS 343 Operating Systems, Winter 2021 Paging Lab: Implementing Virtual Address Spaces

CS 343 Operating Systems, Winter 2021 Paging Lab: Implementing Virtual Address Spaces 1 Introduction The purpose of this lab is to introduce you to virtual memory by implementing virtual address spaces us- ing paging. Paging requires you to think at a deep level about indirection and its management via joint hardware/software mechanisms. In this lab, you will build an implementation of virtual memory using x64 paging within NK’s address space abstraction. You may work in a group of up to three people in this lab. Clarifications and revisions will be posted to the course discussion group. 2 Setup You can work on this lab on any modern Linux system, but our class server, Moore, has been specifically set up for it. This lab will work best on our class server, Moore. Although you can set up your own machine with a special build of QEMU by following a guide on Piazza. We will describe the details of how to access the lab repo via Github Classroom on Piazza. You will use this information to clone the assignment repo using a command like this: server> git clone [url] This will give you the entire codebase and history of the Nautilus kernel framework (“NK”), just as in the Getting Started Lab. As before, you may want to use chmod to control access to your directory. Important! You will need to make sure you have a valid display for NK to run. You can get that through FastX or with ssh -Y. See the Getting Started Lab for more details. To start, you will need to configure the kernel: server> cd [assignment-directory] server> git checkout paginglab server> cp configs/cs343-paginglab-config .config Note that you’ll be working on the paginglab branch, and this is also where you will want to push updates. -

W4118: Xv6 and Linux Processes

W4118: xv6 and Linux processes Instructor: Junfeng Yang xv6 processes How to create the first user process fork() exit() wait() kill() exec() sleep() wakeup() 2 Create the first user process Idea: create a fake trap frame, then reuse trap return mechanism userinit() in proc.c . allocproc() in vm.c allocates PCB, sets trap return address to trapret in trapasm.S, and sets “saved” kernel CPU context . inituvm() in vm.c sets up user space • Allocates a physical page for the process, sets up page table, and copies initcode . Set up fake trap frame . Set up current working directory 3 Init process’s kernel stack SS=SEG_UDATA ESP=PGSIZE EFLAGS=FL_IF trapret: // trapasm.S CS=SEG_UDATA popal EIP=0 … struct trapframe Err code=0 iret Trapno=0 DS=SEG_UDATA … forkret: // proc.c EAX=0 … … ret “return” address trapret forkret “saved” EIP EBP=0 struct context EBX=0 swtch: // swtch.S … ESI=0 popl %edi EDI=0 proc->context popl %esi popl %ebx popl %ebp ret 4 initcode.S // equivalent C code char init[] = “/init\0”; char *argv = {init, 0}; exec(init, argv); for(;;) exit(); Assembly code that . Sets up system call arguments . Moves SYS_exec to EAX . Traps into kernel via INT 64 Execute init generated from init.c Compiled and linked into kernel . Makefile 5 fork() sysproc.c, proc.c Allocate new PCB and stack . Set up EIP of child to forkret trapret Copy address space . Copy both page tables and physical pages . Can you do better? Set parent pointer Copy parent’s trap frame Change EAX in trap frame so that child returns 0 Copy open file table -

CS 1550 Lab 1 – Xv6 Introduction Setup and Exercise

CS 1550 Lab 1 – xv6 Introduction Setup and exercise Teaching Assistant Xiaoyu (Veronica) Liang CS 1550 – Kernel Space vs User Space • Hardware Resources • CPU • Memory (Address space) • I/O devices (Disk, mouse, video card, sound, network, etc.) • Power and System Management User program Operating System Hardware CS 1550 – Kernel Space vs User Space • Abstraction • Hides details of different hardware configurations • Applications do not need to be tailored for each possible device that might be present on a system • Arbitration • Manages access to shared hardware resources • Enables multiple applications to share the same hardware simultaneously • OS is just another software User program Operating System Hardware CS 1550 – Kernel Space vs User Space • OS is just another software • User applications should not change the kernel(OS software) User program Operating System Hardware CS 1550 – Kernel Space vs User Space • User space • Less privileged memory space where user processes execute • Kernel space • Privileged memory space where the OS main process resides • No User application should be able to change User Space Kernel Space Hardware CS 1550 – Kernel Space vs User Space • System Call • User processes have to do system calls to access the OS resources and Hardware User Space Kernel Space User process 3 OS process User User process 1 process 2 System calls CS 1550 – Kernel Space vs User Space • System Call (OS function) • User processes have to do system calls to access the OS resources and Hardware User Space Kernel Space Hardware User CPU process 3 OS process User User Device I/O devices process 1 process 2 System calls Driver System Call - exercise CS 1550 – xv6 • Simple Unix-like teaching operating system, developed in 2006.