Life History Notes on Three Tropical American Cuckoos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

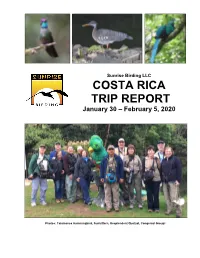

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Maya Knowledge and "Science Wars"

Journal of Ethnobiology 20(2); 129-158 Winter 2000 MAYA KNOWLEDGE AND "SCIENCE WARS" E. N. ANDERSON Department ofAnthropology University ofCalifornia, Riverside Riverside, CA 92521~0418 ABSTRACT.-Knowledge is socially constructed, yet humans succeed in knowing a great deal about their environments. Recent debates over the nature of "science" involve extreme positions, from claims that allscience is arbitrary to claims that science is somehow a privileged body of truth. Something may be learned by considering the biological knowledge of a very different culture with a long record of high civilization. Yucatec Maya cthnobiology agrees with contemporary international biological science in many respects, almost all of them highly specific, pragmatic and observational. It differs in many other respects, most of them highly inferential and cosmological. One may tentatively conclude that common observation of everyday matters is more directly affected by interaction with the nonhuman environment than is abstract deductive reasoning. but that social factors operate at all levels. Key words: Yucatec Maya, ethnoornithology, science wars, philosophy ofscience, Yucatan Peninsula RESUMEN.-EI EI conocimiento es una construcci6n social, pero los humanos pueden aprender mucho ce sus alrededores. Discursos recientes sobre "ciencia" incluyen posiciones extremos; algunos proponen que "ciencia" es arbitrario, otros proponen que "ciencia" es verdad absoluto. Seria posible conocer mucho si investiguemos el conocimiento biol6gico de una cultura, muy difcrente, con una historia larga de alta civilizaci6n. EI conodrniento etnobiol6gico de los Yucatecos conformc, mas 0 menos, con la sciencia contemporanea internacional, especial mente en detallas dcrivadas de la experiencia pragmatica. Pero, el es deferente en otros respectos-Ios que derivan de cosmovisi6n 0 de inferencia logical. -

Checklistccamp2016.Pdf

2 3 Participant’s Name: Tour Company: Date#1: / / Tour locations Date #2: / / Tour locations Date #3: / / Tour locations Date #4: / / Tour locations Date #5: / / Tour locations Date #6: / / Tour locations Date #7: / / Tour locations Date #8: / / Tour locations Codes used in Column A Codes Sample Species a = Abundant Red-lored Parrot c = Common White-headed Wren u = Uncommon Gray-cheeked Nunlet r = Rare Sapayoa vr = Very rare Wing-banded Antbird m = Migrant Bay-breasted Warbler x = Accidental Dwarf Cuckoo (E) = Endemic Stripe-cheeked Woodpecker Species marked with an asterisk (*) can be found in the birding areas visited on the tour outside of the immediate Canopy Camp property such as Nusagandi, San Francisco Reserve, El Real and Darien National Park/Cerro Pirre. Of course, 4with incredible biodiversity and changing environments, there is always the possibility to see species not listed here. If you have a sighting not on this list, please let us know! No. Bird Species 1A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tinamous Great Tinamou u 1 Tinamus major Little Tinamou c 2 Crypturellus soui Ducks Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 3 Dendrocygna autumnalis u Muscovy Duck 4 Cairina moschata r Blue-winged Teal 5 Anas discors m Curassows, Guans & Chachalacas Gray-headed Chachalaca 6 Ortalis cinereiceps c Crested Guan 7 Penelope purpurascens u Great Curassow 8 Crax rubra r New World Quails Tawny-faced Quail 9 Rhynchortyx cinctus r* Marbled Wood-Quail 10 Odontophorus gujanensis r* Black-eared Wood-Quail 11 Odontophorus melanotis u Grebes Least Grebe 12 Tachybaptus dominicus u www.canopytower.com 3 BirdChecklist No. -

Studying an Elusive Cuckoo Sarah C

INNER WORKINGS INNER WORKINGS Studying an elusive cuckoo Sarah C. P. Williams fi Science Writer a eld site in Panama operated by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. “They only build nests overhanging water and so you need to boat—often through In a single nest, perched on a branch over- A dozen feet away, researchers peer out of waters with lots of crocodiles—to see the hanging a marshy river in Panama, four birds an idling boat, binoculars to their faces as nests or catch the birds for banding and jostle for space. The birds all belong to a they count the birds, the eggs, and note the blood samples.” species of cuckoo called the Greater Ani, and colors of the bands clamped around each However, the communal nesting habits of each one has offspring in the communal nest. bird’sleg. the Greater Ani has Riehl intrigued. She’s The birds take turns warming the heap of eggs “The Anis are really hard to study,” says spent the past five years tracking birds, in- and looking out for predators, teaming to- Christina Riehl, a junior fellow with the stalling video cameras above their nests, and gether to face the challenges of rearing young. Harvard Society of Fellows, who works at studying the genetics of each generation of birds to understand their behaviors. TheAnisnestingroupsoftwotofour male-femalepairs,addinguptofourtoeight adults per nest. Riehl has discovered that the bigger the group, the more young that survive, suggesting a clear advantage to the cooperation. However, there’s competition in the mix too; before a female lays her own eggs, she’ll try to kick other females’ eggs out of the nest. -

“Italian Immigrants” Flourish on Long Island Russell Burke Associate Professor Department of Biology

“Italian Immigrants” Flourish on Long Island Russell Burke Associate Professor Department of Biology talians have made many important brought ringneck pheasants (Phasianus mentioned by Shakespeare. Also in the contributions to the culture and colchicus) to North America for sport late 1800s naturalists introduced the accomplishments of the United hunting, and pheasants have survived so small Indian mongoose (Herpestes javan- States, and some of these are not gen- well (for example, on Hofstra’s North icus) to the islands of Mauritius, Fiji, erally appreciated. Two of the more Campus) that many people are unaware Hawai’i, and much of the West Indies, Iunderappreciated contributions are that the species originated in China. Of supposedly to control the rat popula- the Italian wall lizards, Podarcis sicula course most of our common agricultural tion. Rats were crop pests, and in most and Podarcis muralis. In the 1960s and species — except for corn, pumpkins, cases the rats were introduced from 1970s, Italian wall lizards were imported and some beans — are non-native. The Europe. Instead of eating lots of rats, the to the United States in large numbers for mongooses ate numerous native ani- the pet trade. These hardy, colorful little mals, endangering many species and lizards are common in their home coun- Annual Patterns causing plenty of extinctions. They also try, and are easily captured in large num- 3.0 90 became carriers of rabies. There are 80 2.5 bers. Enterprising animal dealers bought 70 many more cases of introductions like them at a cut rate in Italy and sold them 2.0 60 these, and at the time the scientific 50 1.5 to pet dealers all over the United States. -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Reactivating the Lake Junín Giant Frog Monitoring Program

December 2020 AMPHIBIAN SURVIVAL ALLIANCE NEWTSLETTER Got a story you want to share? Drop Candace an email today! [email protected] Stories from our partners around the world © Rogger Angel Moreno Lino Moreno Angel © Rogger Reactivating the Lake Junín Giant Frog monitoring program By Rogger Angel Moreno Lino, Luis and economy; businesses and NGOs In this way, ASA partner Grupo Castillo Roque and Roberto Elias have stopped their activities and RANA participated in a project for Piperis. Grupo RANA (Peru) and reduced their budgets among other the monitoring and surveillance of Denver Zoological Foundation (U.S.) things (Smith-Bingham & Harlharan, populations of the Lake Junín Giant [email protected] 2020; Crothers, 2020). However, Frog (Telmatobius macrostomus) solidarity among people and institu- and the Junín ‘Wanchas’ (Telma- The world is going through difficult tions has allowed activities to be tobius brachydactylus) in three times due to the COVID-19 pan- progressively reactivated, though protected natural areas (Junín Na- demic (WWF, 2020). Many people following rigorous biosecurity meas- tional Reserve, Historic Sanctuary of have been affected in their health ures. Chacamarca and Huayllay National Page 1 Sanctuary). These activities were by Pablo Miñano Lecaros. The park (CCPH), the presence of six adult led by the Denver Zoological Foun- rangers Winy Arias López, Eduardo frogs was recorded around 500 dation and funded by the National Ruiz and Duane Martínez supported meters from our monitoring point Geographic Society and followed the the activities. at the south of the Junín National biosecurity measures recommended As part of the preliminary results, Reserve. by the Ministry of Health of Peru we report three adults of the Junín It should be noted that the CCPH (D.S. -

TAS Trinidad and Tobago Birding Tour June 14-24, 2012 Brian Rapoza, Tour Leader

TAS Trinidad and Tobago Birding Tour June 14-24, 2012 Brian Rapoza, Tour Leader This past June 14-24, a group of nine birders and photographers (TAS President Joe Barros, along with Kathy Burkhart, Ann Wiley, Barbara and Ted Center, Nancy and Bruce Moreland and Lori and Tony Pasko) joined me for Tropical Audubon’s birding tour to Trinidad and Tobago. We were also joined by Mark Lopez, a turtle-monitoring colleague of Ann’s, for the first four days of the tour. The islands, which I first visited in 2008, are located between Venezuela and Grenada, at the southern end of the Lesser Antilles, and are home to a distinctly South American avifauna, with over 470 species recorded. The avifauna is sometimes referred to as a Whitman’s sampler of tropical birding, in that most neotropical bird families are represented on the islands by at least one species, but never by an overwhelming number, making for an ideal introduction for birders with limited experience in the tropics. The bird list includes two endemics, the critically endangered Trinidad Piping Guan and the beautiful yet considerably more common Trinidad Motmot; we would see both during our tour. Upon our arrival in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago’s capital, we were met by the father and son team of Roodal and Dave Ramlal, our drivers and bird guides during our stay in Trinidad. Ruddy Ground-Dove, Gray- breasted Martin, White-winged Swallow and Carib Grackle were among the first birds encountered around the airport. We were immediately driven to Asa Wright Nature Centre, in the Arima Valley of Trinidad’s Northern Range, our base of operations for the first seven nights of our tour. -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Crotophaga Ani (Smooth-Billed Ani)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Crotophaga ani (Smooth-billed Ani) Family: Cuculidae (Cuckoos and Anis) Order: Cuculiformes (Cuckoos, Anis and Turacos) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Smooth-billed ani, Crotophaga ani. [http://www.hoteltinamu.com/wp-content/uploads/Crotophaga-ani-Garrapatero-Piquiliso-Smooth-billed-Ani- Tb1.jpg, downloaded 16 November 2014] TRAITS. A black, glossy bird with a slight purple sheen on its wings and tail (Fig. 1). Adults range from 30-35cm in length from bill (beak) to tail (Evans, 1990). The average length of one wing in males is 155mm and in females is 148mm (Ffrench, 2012). There is little sexual dimorphism between sexes, except a slight size and weight difference (Davis, 1940). It has a large, black bill that forms a high ridge on the upper beak which is curved downwards. This gives it a unique appearance and the smoothness of its bill distinguishes it from other species e.g. the groove-billed ani. Its tail is long, flattened and rounded at the tip and it is almost half the length of the bird. Its feet are black, with the toes in the zygodactyl arrangement; one long and short digit facing forward and one long and short digit facing backwards. This allows them to walk on the ground instead of hopping like other birds. Anis are poor fliers; their flight is said to look laboured and awkward (Davis, 1940). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour ECOLOGY. Like others of their family, smooth-billed anis are an arboreal species. -

Studies on the Taxonomy, Morphology, and Biology of Prosthogonimus Macrorchis Macy, a Common Oviduct Fluke of Domestic Fowls in North America

E t Technical Bulletin 98 June 1934 University of Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station Studies on the Taxonomy, Morphology, and Biology of Prosthogonimus Macrorchis Macy, A Common Oviduct Fluke of Domestic Fowls in North America Ralph W. Macy UNIVERSITY FARM, ST. PAUL University of Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station Studies on the Taxonomy, Morphology, and Biology of Prosthogonimus Macrorchis Macy, A Common Oviduct Fluke of Domestic Fowls in North America Ralph W. Macy UNIVERSITY FARM, ST. PAUL LIFE CYCLE OF TIIE OVIDUCT FLTJKE FROM HEN TO SNAIL, TO DRAGONFLY NAIADS, AND BACK TO FOWLS WHICH FEED ON THESE INSECTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Special acknowledgment for aid in the course of this work and for making possible its completion is due Dr. W. A. Riley and Dr. D. E. Minnich, Chair=11 of the University Department of Zoology. Many others have contributed. To Dr. F. B. Hutt and his staff I offer my sincere thanks for their hearty co-operation. Others who have aided me materially are Drs. A. R. Ringoen, R. L. Donovan, A. A. Granovsky, M. N. Levine, Miss Ethel Slider, and Messrs. Gustav Swanson and W. W. Crawford. My wife, also, has helped at all times, but especially with mollusc collections and dissections. I am likewise very grateful to Dr. James G. Needham of Cornell University for checking the i,denti- fication of the important dragonfly hosts, and to Dr. Frank C. Baker of the University of Illinois for similar help with the snail host. CONTENTS Page Introduction 7 General methods and technic 8 Taxonomy 9 Specific diagnosis of Prosthogonimus