Timeless Heritage: a History of the Forest Service in the Southwest I Where There Are Errors, and We Hope They Are Nonexistent Or Few, We Accept Full Responsibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana Chiricahuensis)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana chiricahuensis) Final Recovery Plan April 2007 CHIRICAHUA LEOPARD FROG (Rana chiricahuensis) RECOVERY PLAN Southwest Region U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and are sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, state agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director, or Director, as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature citation of this document should read as follows: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana chiricahuensis) Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Southwest Region, Albuquerque, NM. 149 pp. + Appendices A-M. Additional copies may be obtained from: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Field Office Southwest Region 2321 West Royal Palm Road, Suite 103 500 Gold Avenue, S.W. -

LIGHTNING FIRES in SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS T

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. LIGHTNING FIRES IN SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS t . I I LIGHT~ING FIRES IN SOUTHWESTERN FORESTS (l) by Jack S. Barrows Department of Forest and Wood Sciences College of Forestry and Natural Resources Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 (1) Research performed for Northern Forest Fire Laboratory, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station under cooperative agreement 16-568 CA with Rocky Mountain For est and Range Experiment Station. Final Report May 1978 n LIB RARY COPY. ROCKY MT. FO i-< t:S'f :.. R.l.N~ EX?f.lt!M SN T ST.A.1101'1 . - ... Acknowledgementd r This research of lightning fires in Sop thwestern forests has been ? erformed with the assistan~e and cooperation of many individuals and agencies. The idea for the research was suggested by Dr. Donald M. Fuquay and Robert G. Baughman of the Northern Forest Fire Laboratory. The Fire Management Staff of U. S. Forest Service Region Three provided fire data, maps, rep~rts and briefings on fire p~enomena. Special thanks are expressed to James F. Mann for his continuing assistance in these a ctivities. Several members of national forest staffs assisted in correcting fire report errors. At CSU Joel Hart was the principal graduate 'research assistant in organizing the data, writing computer programs and handling the extensive computer operations. The initial checking of fire data tapes and com puter programming was performed by research technician Russell Lewis. Graduate Research Assistant Rick Yancik and Research Associate Lee Bal- ::. -

USGS Open-File Report 2005-1190, Table 1

TABLE 1 GEOLOGIC FIELD-TRAINING OF NASA ASTRONAUTS BETWEEN JANUARY 1963 AND NOVEMBER 1972 The following is a year-by-year listing of the astronaut geologic field training trips planned and led by personnel from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Branches of Astrogeology and Surface Planetary Exploration, in collaboration with the Geology Group at the Manned Spacecraft Center, Houston, Texas at the request of NASA between January 1963 and November 1972. Regional geologic experts from the U.S. Geological Survey and other governmental organizations and universities s also played vital roles in these exercises. [The early training (between 1963 and 1967) involved a rather large contingent of astronauts from NASA groups 1, 2, and 3. For another listing of the astronaut geologic training trips and exercises, including all attending and the general purposed of the exercise, the reader is referred to the following website containing a contribution by William Phinney (Phinney, book submitted to NASA/JSC; also http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/alsj/ap-geotrips.pdf).] 1963 16-18 January 1963: Meteor Crater and San Francisco Volcanic Field near Flagstaff, Arizona (9 astronauts). Among the nine astronaut trainees in Flagstaff for that initial astronaut geologic training exercise was Neil Armstrong--who would become the first man to step foot on the Moon during the historic Apollo 11 mission in July 1969! The other astronauts present included Frank Borman (Apollo 8), Charles "Pete" Conrad (Apollo 12), James Lovell (Apollo 8 and the near-tragic Apollo 13), James McDivitt, Elliot See (killed later in a plane crash), Thomas Stafford (Apollo 10), Edward White (later killed in the tragic Apollo 1 fire at Cape Canaveral), and John Young (Apollo 16). -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

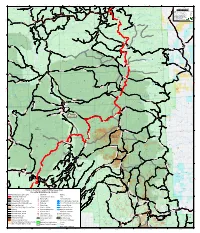

Trails in the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Area Recently Maintained & Cleared

l y R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. r l R. 10 W. t R. 9 W. R. 8 W. i r e t e 108°0'W m 107°45'W a v w o W a P S S le 11 Sawmill t Boundary Tank F t 6 40 10 i 1 6 Peak L 5 6 7M 10 11 9 1:63,360 0 0 8 9 12 8 8350 anyon Houghton Spring 4 7 40 7 5 7 T e C 1 in = 1 miles 11 12 4 71 7 7 0 Klin e C 10 0 C H 6 0 7 in Water anyon 8 9 6 a 4 0 Ranch P 4065A 7 Do 6 n 4 073Q (printed on 36" x 42" portrait layout) Houghton ag Z y 4 Well 12 Corduroy Corral y Doagy o 66 11 n 5 aska 10 Spr. Spr. Tank K Al 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 9 Corduroy Tank 1 1 14 13 7 2 15 5 0 4 Miles 5 Doagie Spr. 5 16 9 Beechnut Tank 4 0 17 6 13 18 n 8 14 yo 1 15 an Q C Deadman Tank 16 D Coordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 12NTransverse Mercator 3 3 3 17 0 r C 2 Sawmill 1 0 Rock 7 18 a Alamosa 13 w 6 1 Spr. Core 14 Attention: Reilly 6 Dirt Tank 8 15 0 Peak 14 Dev. Tank 3 Clay 4 15 59 16 Gila National Forest uses the most current n 0 16 S o 17 13 Santana 8163 1 17 3 y Doubleheader #2 Tank 18 Fence Tank Cr. -

Warfare in a Fragile World: Military Impact on the Human Environment

Recent Slprt•• books World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbook 1979 World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbooks 1968-1979, Cumulative Index Nuclear Energy and Nuclear Weapon Proliferation Other related •• 8lprt books Ecological Consequences of the Second Ihdochina War Weapons of Mass Destruction and the Environment Publish~d on behalf of SIPRI by Taylor & Francis Ltd 10-14 Macklin Street London WC2B 5NF Distributed in the USA by Crane, Russak & Company Inc 3 East 44th Street New York NY 10017 USA and in Scandinavia by Almqvist & WikseH International PO Box 62 S-101 20 Stockholm Sweden For a complete list of SIPRI publications write to SIPRI Sveavagen 166 , S-113 46 Stockholm Sweden Stoekholol International Peace Research Institute Warfare in a Fragile World Military Impact onthe Human Environment Stockholm International Peace Research Institute SIPRI is an independent institute for research into problems of peace and conflict, especially those of disarmament and arms regulation. It was established in 1966 to commemorate Sweden's 150 years of unbroken peace. The Institute is financed by the Swedish Parliament. The staff, the Governing Board and the Scientific Council are international. As a consultative body, the Scientific Council is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. Governing Board Dr Rolf Bjornerstedt, Chairman (Sweden) Professor Robert Neild, Vice-Chairman (United Kingdom) Mr Tim Greve (Norway) Academician Ivan M£ilek (Czechoslovakia) Professor Leo Mates (Yugoslavia) Professor -

Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government Neal Devins

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 69 | Issue 4 Article 3 5-2016 Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government Neal Devins Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Neal Devins, Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government, 69 Vanderbilt Law Review 935 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol69/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking Judicial Minimalism: Abortion Politics, Party Polarization, and the Consequences of Returning the Constitution to Elected Government Neal Devins* IN TROD U CTION ............................................................................... 935 I. MINIMALISM THEORY AND ABORTION ................................. 939 II. WHAT ABORTION POLITICS TELLS US ABOUT JUDICIAL M INIMALISM ........................................................ 946 A . R oe v. W ade ............................................................. 947 B . From Roe to Casey ................................................... 953 C. Casey and Beyond .................................................. -

BULLETIN of the ALLYN MUSEUM 3621 Bayshore Rd

BULLETIN OF THE ALLYN MUSEUM 3621 Bayshore Rd. Sarasota, Florida 33580 Published By The Florida State Museum University of Florida Gainesville. Florida 32611 Number 107 30 December 1986 A REVIEW OF THE SATYRINE GENUS NEOMINOIS, WITH DESCRIPriONS OF THREE NEW SUBSPECIES George T. Austin Nevada State Museum and Historical Society 700 Twin Lakes Drive, Las Vegas, Nevada 89107 In recent years, revisions of several genera of satyrine butterflies have been undertaken (e. g., Miller 1972, 1974, 1976, 19781. To this, I wish to add a revision of the genus Neominois. Neominois Scudder TYPE SPECIES: Satyrus ridingsii W. H. Edwards by original designation (Scudder 1875b, p. 2411 Satyrus W. H. Edwards (1865, p. 2011, Rea.kirt (1866, p. 1451, W. H. Edwards (1872, p. 251, Strecker (1873, p. 291, W. H. Edwards (1874b, p. 261, W. H. Edwards (1874c, p. 5421, Mead (1875, p. 7741, W. H. Edwards (1875, p. 7931, Scudder (1875a, p. 871, Strecker (1878a, p. 1291, Strecker (1878b, p. 1561, Brown (1964, p. 3551 Chionobas W. H. Edwards (1870, p. 1921, W. H. Edwards (1872, p. 271, Elwes and Edwards (1893, p. 4591, W. H. Edwards (1874b, p. 281, Brown (1964, p. 3571 Hipparchia Kirby (1871, p. 891, W. H. Edwards (1877, p. 351, Kirby (1877, p. 7051, Brooklyn Ent. Soc. (1881, p. 31, W. H. Edwards (1884, p. [7)l, Maynard (1891, p. 1151, Cockerell (1893, p. 3541, Elwes and Edwards (1893, p. 4591, Hanham (1900, p. 3661 Neominois Scudder (1875b, p. 2411, Strecker (1876, p. 1181, Scudder (1878, p. 2541, Elwes and Edwards (1893, p. 4591, W. -

Academic Zodiac & RTRRT Publications

Oh, look: it's full of stars! http://lulu.com/astrology The Happiness Formula is 22:16. First published by Klaudio Zic Publications, 2011 http://stores.lulu.com/astrology Copyright © 2011 By Klaudio Zic. All Rights Reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, for commercial purposes or otherwise, without the written permission of the Author. The names of dedicated publications are normally given in italics. Academic Zodiac & RTRRT Publications Copyright © 2011 by Klaudio Zic, all rights reserved. http://www.lulu.com/astrology Is there a happiness formula? If there is one, we believe we have found it. From time immemorial, we have been told to tell the truth in order to be happy forever after; well, here it is: your own true horoscope according to the original zodiac. If you were looking for truth, the search ends here: you have found the Academic Zodiac. Your true stars will help your original mind out of its frozen niche. A bit dusty after years of hibernation, your original self bursts open within a world of infinite possibilities. You can create and recreate events much as you can discreate the unwanted ones forever. Buss the slumbering princess, kiss the frog & prince charming and welcome to your enchanted kingdom full of goodies and birthright charms. Academic Zodiac & RTRRT Publications How does one find an appropriate publication? The publication of your own choice is found by searching the lulu.com site for relevant results. The helpful site inkmesh.com is particularly useful in determining price range, e.g. -

The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: an Administrative History. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 266 012 SE 046 389 AUTHOR Paige, John C. TITLE The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History. INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, D.C. REPORT NO NPS-D-189 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 293p.; Photographs may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Conservation (Environment); Employment Programs; *Environmental Education; *Federal Programs; Forestry; Natural Resources; Parks; *Physical Environment; *Resident Camp Programs; Soil Conservation IDENTIFIERS *Civilian Conservation Corps; Environmental Management; *National Park Service ABSTRACT The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) has been credited as one of Franklin D. Roosevelt's most successful effortsto conserve both the natural and human resources of the nation. This publication provides a review of the program and its impacton resource conservation, environmental management, and education. Chapters give accounts of: (1) the history of the CCC (tracing its origins, establishment, and termination); (2) the National Park Service role (explaining national and state parkprograms and co-operative planning elements); (3) National Park Servicecamps (describing programs and personnel training and education); (4) contributions of the CCC (identifying the major benefits ofthe program in the areas of resource conservation, park and recreational development, and natural and archaeological history finds); and (5) overall -

Inside Report 2010

® 200 9–2010 Annual Repo rt FOO D TAX DEFEATE D Again About the Cover The cover features a photograph of Dixon’s apple orchard at har - vest time. Dixon’s, located in Peña Blanca, New Mexico, close to Cochiti, is a New Mexico institution. It was founded by Fred and Faye Dixon in 1943, and is currently run by their granddaughter, Becky, and her husband, Jim. The photo was taken by Mark Kane, a Santa Fe-based photographer who has had many museum and Design gallery shows and whose work has been published extensively. Kristina G. Fisher More of his photos can be seen at markkane.net. The inside cover photo was taken by Elizabeth Field and depicts tomatoes for sale Design Consultant at the Santa Fe Farmer’s Market. Arlyn Eve Nathan Acknowledgments Pre-Press We wish to acknowledge the Albuquerque Journal , the Associated Peter Ellzey Press, the Deming Headlight , the Las Cruces Sun-News , Paul Gessing and the Rio Grande Foundation, the Santa Fe New Mexican , the Printe r Santa Fe Reporter, and the Truth or Consequences Herald for Craftsman Printers allowing us to reprint the excerpts of articles and editorials that appear in this annual report. In addition, we wish to thank Distribution Elizabeth Field, Geraint Smith, Clay Ellis, Sarah Noss, Pam Roy, Frank Gonzales and Alex Candelaria Sedillos, and Don Usner for their permission to David Casados reprint the photographs that appear throughout this annual report. Permission does not imply endorsement. Production Manager The paper used to print this report meets the sourcing requirements Lynne Loucks Buchen established by the forest stewardship council.