Ontologies of Community in Postmodernist American Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title Page of Her First Collection of Poems, the Close Chaplet (1926), Following Their Divorce in 1925

! 1! “Hospitality to Words”: Laura Riding’s American Inheritance and Inheritors Philip John Lansdell Rowland Royal Holloway, University of London Submitted for the Degree of PhD ! 3! Abstract This thesis situates the work of Laura Riding in an American tradition of “hospitality to words” extending from Emerson and Emily Dickinson through Gertrude Stein to John Ashbery and contemporary language-oriented writing. The theme is introduced in terms of her linguistic and spiritual ideal of home as a place of truthful speaking, related in turn to her identity as an American writer who renounced the craft of poetry in mid-career. First, Riding’s poetry is “hospitable” in ways akin to Dickinson’s, broadly characterized by Riding’s term, “linguistic intimateness.” There are similarities in their word-conjunctions and styles of poetic argument, as well as their ideas of poetry as “house of possibility” and spiritual home. Riding’s work is then compared with that of her older friend of the late 1920s, Gertrude Stein. The chapter details the shift in Riding’s critical view of Stein; then focuses on the similarly “homely” characteristics of their prose writing and poetics, with particular reference made to Riding’s “Steinian” poems. The central chapters clarify Riding’s conception of truth and related questions of authority, history and responsibility. Chapter 4 explains her poetic vision of “the end of the world” as the introduction to a new world and potentially a new home, and chapter 5 extends the account to include her post-poetic work, The Telling compared to her earlier, collaborative The World and Ourselves. -

{PDF EPUB} the Sky Changes by Gilbert Sorrentino Gilbert Sorrentino

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Sky Changes by Gilbert Sorrentino Gilbert Sorrentino. Gilbert Sorrentino (born April 27, 1929 in Brooklyn , New York City , † May 18, 2006 in New York City) was an American writer. In 1956 Sorrentino and his friends from Brooklyn College, including childhood friend Hubert Selby Jr., founded the literary magazine Neon , which was published until 1960. After that he was one of the editors of Kulchur magazine . After working closely with Selby on the manuscript of Last Exit to Brooklyn in 1964, he became an editor at underground publisher Grove Press (from 1965 to 1970). He supervised u. a. The Autobiography of Malcolm X . Sorrentino was Professor of English at Stanford University from 1982 to 1999 . Among his students were the writers Jeffrey Eugenides and Nicole Krauss. His son Christopher Sorrentino is the novelist of Sound on Sound and Trance. Sorrentino's first novel, The Sky Changes , was published in 1966 . Other important novels were Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things , Blue Pastoral and Mulligan Stew. Sorrentino is one of the better known authors of the literary postmodern . His novels Mulligan Stew and The Apparent Deflection of Starlight , also translated into German, have a metafictional character. Gilbert Sorrentino. The maverick American novelist and poet Gilbert Sorrentino, who has died aged 77, is best known for Mulligan Stew (1979), a novel drawing upon characters from Dashiell Hammett, F Scott Fitzgerald and Flann O'Brien, and one from a James Joyce footnote. The labyrinthine ways of this freewheeling escapade make it no surprise that Sorrentino's favourite novel was Tristram Shandy. -

The Superseding, a Prague Nocturne 141

| | | | The Return of Král Majáles PRAGUE’S INTERNATIONAL LITERARY RENAISSANCE 990-00 AN ANTHOLOGY | Edited by LOUIS ARMAND Copyright © Louis Armand, 2010 Copyright © of individual works remains with the authors Copyright © of images as captioned Published 1 May, 2010 by Univerzita Karlova v Praze Filozofická Fakulta Litteraria Pragensia Books Centre for Critical & Cultural Theory, DALC Náměstí Jana Palacha 2 116 38 Praha 1, Czech Republic All rights reserved. This book is copyright under international copyright conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the copyright holders. Requests to publish work from this book should be directed to the publish- ers. ‘Cirkus’ © 2010 by Myla Goldberg. Used by permission of Wendy Schmalz Agency. The publication of this book has been partly supported by research grant MSM0021620824 “Foundations of the Modern World as Reflected in Literature and Philosophy” awarded to the Faculty of Philosophy, Charles University, Prague, by the Czech Ministry of Education. All reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright holders. | Cataloguing in Publication Data The Return of Král Majáles. Prague’s International Literary Renaissance 1990-2010 An Anthol- ogy, edited by Louis Armand.—1st ed. p. cm. ISBN 978-80-7308-302-1 (pb) 1. Literature. 2. Prague. 3. Central Europe. I. Armand, Louis. II. Title Printed in the Czech Republic by PB Tisk Cover, typeset & design © lazarus Cover image: Allen Ginsberg in Prague, 1965. Photo: ČTK. Inside pages: 1. Allen Ginsberg in Prague, 1965. Photo: ČTK. -

CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty

APPARATUS POETICA: THE QUESTION OF TECHNOLOGY IN MID-TWENTIETH- CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Avery Slater August 2014 © 2014 Avery Slater APPARATUS POETICA: THE QUESTION OF TECHNOLOGY IN MID-TWENTIETH- CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY Avery Slater, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 “Apparatus Poetica” considers how four poets in the late modernist tradition reconceive the potentials of poetic language in order to address the question of advanced technology. Outlining challenges posed to language by communications industries, information theory, computation, and the threat of nuclear war, I show how four poets—James Merrill, Muriel Rukeyser, H.D., and Jack Spicer—explore affinities and crucial distinctions between poetry and technology. Through their experiments in what I call “apparatus poetics,” these poets denaturalize culturally embedded assumptions surrounding technology’s “neutrality” and poetry’s expressive “purity.” They do so through procedural innovations in the genre of the poetic epic, that form not coincidentally deemed by modernist anthropologists as the earliest human memory-technology. I begin with a discussion of how the montage apparatus of testimonial poetry in Rukeyser’s The Book of the Dead works to indict industrial capital’s technological tactics of historical effacement. I next discuss how Jack Spicer, working as a structural linguist in the age of IBM, uses a late modernist method, the “serial lyric,” to set up a confrontation between poetic consciousness and language. Spicer casts the old predicament of thought’s alienation from language in a new light defined by contemporary forms of technological emergence (especially computational intelligence). -

Catalogfall14 Spring15-G586.Pdf

DZANC STAFF Steven Gillis, Co-Founder and Publisher Dan Wickett, Co-Founder Guy intoci, Editor-in-Chief Jeffery Gleaves, Director of Marketing & Publicity Michelle Dotter, Editor Pat Walsh, Director of Foreign Rights Steven Seighman, Design BOARD OF DIRECTORS Steven Gillis (Chair), Jeff Parker, Jeremy Chamberlain BOARD EMERITUS Doug Wilson, James Rosenfeld, Peter Fayroian NATIONAL COUNCIL Fred Ramey, Jessica Stockton Bagnulo ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dzanc Books is supported, in part, by grants from the Community Founda- tion of SE Michigan, specifically targeted grants from John and Jean Wickett, the Meijer Foundation, and various individuals Visit our website: www.dzancbooks.org 1 WELCOME TO DZANC BOOKS TABLE OF CONTENTS Shortly after opening our doors in 2006, Dzanc Books was hailed as “the future of publishing” by Publishers Weekly. A fully invested publishing house with print distribution through Consortium, and eBook distribution through Open Road Media, Dzanc Books is committed to not only publishing great DZANC FRONTLIST BOOKS.................................4 works, but promoting our authors through print and online media, author tours, and through audio/visual THE OLD REACTOR media. In our first few years, Dzanc authors have been reviewed everywhere both in print and online, a novel by david ohle OFFERINGS FROM A RUST BELT JOCKEY including the Los Angeles Times Book Review, The Believer, Time Out New York, NewPages, Bookslut, a novel by andrew plattner Mid-American Review, American Book Review, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, Publishers Weekly, A DIFFERENT BED EVERY TIME stories by jac jemc Rain Taxi, Elle Magazine, Vanity Fair, and numerous others. With award-winning authors such as Josip BY LIGHT WE KNEW OUR NAMES Novakovich, Laura van den Berg, and Hesh Kestin, coupled with great emerging writers like Sean McGrady, stories by anne valente Eugene Cross, and Jac Jemc, Dzanc is excited to present the best and the brightest authors writing today. -

WINTER 2018 Rainer Maria Rilke Poems from the Book of Hours

Alexander Kluge Temple of the Scapegoat: Opera Stories • Translated from the German by Isabel Cole and Donna Stonecipher • With photographs Revolving around the opera, these tales are an “archaeological excavation of the slag-heaps of our collective existence” (W. G. Sebald) Combining fact and fiction, each of the one hundred and two tales of Al- exander Kluge’s Temple of the Scapegoat (dotted with photos of famous PBK NDP 1395 operas and their stars) compresses a lifetime of feeling and thought: Kluge is deeply engaged with the opera and an inventive wellspring of narrative FICTION JANUARY notions. The titles of his stories suggest his many turns of mind: “Total Com- mitment,” “Freedom,” “Reality Outrivals Theater,” “The Correct Slowing-Down 5 X 8" 288pp at the Transitional Point Between Terror and an Inkling of Freedom,” “A Crucial Character (Among Persons None of Whom Are Who They Think They Are),” ISBN 978-0-8112-2748-3 and “Deadly Vocal Power vs. Generosity in Opera.” An opera, Kluge says, is a blast furnace of the soul, telling of the great singer Leonard Warren who died EBK 978-0-8112-2749-0 onstage, having literally sung his heart out. Kluge introduces a Tibetan scholar who realizes that opera “is about comprehension and passion. The two never 36 CQ TERRITORY W go together. Passion overwhelms comprehension. Comprehension kills pas- sion. This appears to be the essence of all operas, says Huang Tse-we: she US $18.95 CAN $24.95 also comes to understand that female roles face the harshest fates. Compared to the mass of soprano victims (out of 86,000 operas, 64,000 end with the death of the soprano), the sacrifice of tenors is small (out of 86,000 operas ALSO BY ALEXANDER KLUGE: 1,143 tenors are a write-off).” CINEMA STORIES “Alexander Kluge, that most enlightened of writers.” –W. -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC ARCHIVES & COLLECTIONS / RECENT ACQUISITIONS 15 Academy Street P. O. Box 668 Salisbury, CT 06068 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. [ANTHOLOGY] CUNARD, Nancy, compiler & contributor. Negro Anthology. 4to, illustrations, fold-out map, original brown linen over beveled boards, lettered and stamped in red, top edge stained brown. London: Published by Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co, 1934. First edition, first issue binding, of this landmark anthology. Nancy Cunard, an independently wealthy English heiress, edited Negro Anthology with her African-American lover, Henry Crowder, to whom she dedicated the anthology, and published it at her own expense in an edition of 1000 copies. Cunard’s seminal compendium of prose, poetry, and musical scores chiefly reflecting the black experience in the United States was a socially and politically radical expression of Cunard’s passionate activism, her devotion to civil rights and her vehement anti-fascism, which, not surprisingly given the times in which she lived, contributed to a communist bias that troubles some critics of Cunard and her anthology. Cunard’s account of the trial of the Scottsboro Boys, published in 1932, provoked racist hate mail, some of which she published in the anthology. Among the 150 writers who contributed approximately 250 articles are W. E. B. Du Bois, Arna Bontemps, Sterling Brown, Countee Cullen, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Samuel Beckett, who translated a number of essays by French writers; Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, George Antheil, Ezra Pound, Theodore Dreiser, among many others. -

Harry Mathews Interview Final

loggernaut reading series – summer 2012 Harry Mathews: A Meal Should Last Forever Harry Mathews has written some of the most formally inventive, and perversely moving, American fiction and poetry of the last 50 years. As the American standard-bearer for the otherwise predominantly European OuLiPo, his influence can be felt throughout the cultural sphere. He splits his time between France and Key West, where we conducted this interview last April. Mathews has increasingly seemed to me a sage arbiter not only of all things literary, but also of living well. It made sense, therefore, to ask him a few questions about food and wine and their relationship to literature, all of which I have enjoyed heartily in his presence. This conversation between Mathews, the Key-West-based poet and publisher Arlo Haskell, and myself took place over dinner at the erstwhile Key West Italian restaurant Antonia's. We were joined by Marie Chaix, Mathews's wife, and Ashley Kamen, who by the time you read this will have become Haskell's. -Stuart Krimko Harry Mathews: Is the recorder on now? Arlo Haskell: It is, but we'll pretend like it's not. HM: You've already asked me an extremely recordable question. Stuart Krimko: It was really just an appetizer question. I'd asked you whether anyone had asked you in particular about the ways in which food and wine play into your work. HM: One basic thing is that I don't drink whiskey. I love it, but I don't drink it so much anymore. T.S. Eliot said that he often had a glass or two of whiskey to get the creative juices flowing, which was amazing, coming from him, and quite understandable. -

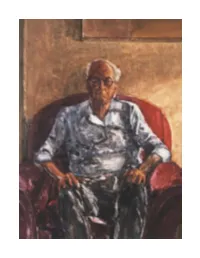

William Bronk

Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk David Clippinger Argotist Ebooks 2 * Cover image by Daniel Leary Copyright © David Clippinger 2012 All rights reserved Argotist Ebooks * Bill in a Red Chair, monotype, 20” x 16” © Daniel Leary 1997 3 The surest, and often the only, way by which a crowd can preserve itself lies in the existence of a second crowd to which it is related. Whether the two crowds confront each other as rivals in a game, or as a serious threat to each other, the sight, or simply the powerful image of the second crowd, prevents the disintegration of the first. As long as all eyes are turned in the direction of the eyes opposite, knee will stand locked by knee; as long as all ears are listening for the expected shout from the other side, arms will move to a common rhythm. (Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power) 4 Neither Us nor Them: Poetry Anthologies, Canon Building and the Silencing of William Bronk 5 Part I “So Large in His Singleness” By 1960 William Bronk had published a collection, Light and Dark (1956), and his poems had appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, Origin, and Black Mountain Review. More, Bronk had earned the admiration of George Oppen and Charles Olson, as well as Cid Corman, editor of Origin, James Weil, editor of Elizabeth Press, and Robert Creeley. But given the rendering of the late 1950s and early 1960s poetry scene as crystallized by literary history, Bronk seems to be wholly absent—a veritable lacuna in the annals of poetry. -

The New American Poetry, 1945-1960 Edited by Donald Allen

THE NEW AMERICAN POETRY, 1945-1960 EDITED BY DONALD ALLEN UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY LOS ANGELES LONDON CONTENTS The New American Poetry: 1945-1960 Preface .......... jri I. Charles Olson (1910-1970) The Kingfishers 2 I, Maximus of Gloucester, to You .... 8 The Songs of Maximus . 11 Maximus, to himself ....... 14 The Death of Europe 16 A Newly Discovered 'Homeric' Hymn ... 22 The Lordly and Isolate Satyrs 24 As the Dead Prey Upon Us 27 Variations Done for Gerald van de Wiele ... 34 The Distances 37 Robert Duncan (1919-1988) The Song of the Borderguard ..... 40 An Owl Is an Only Bird of Poetry .... 41 This Place Rumord To Have Been Sodom ... 44 The Dance 46 The Question 48 A Poem Beginning with a Line by Pindar ... 49 Food for Fire, Food for Thought .... 57 Dream Data 58 XV Contents xvi Denise Levertov (1923-1997) Beyond the End 60 The Hands 61 Merritt Parkway 61 The Way Through 62 The Third Dimension 63 Scenes from the Life of the Peppertrees ... 64 The Sharks 66 The Five-Day Rain 66 Pleasure 67 The Goddess 68 Paul Blackburn (1926-1971) The Continuity 69 The Assistance 69 Night Song for Two Mystics ...... 70 The Problem 72 Sirventes ......... 72 The Once-over ........ 75 The Encounter 76 Robert Creeley (1926) The Innocence ........ 77 The Kind of Act of 77 The Immoral Proposition ...... 78 A Counterpoint ....... 78 The Warning 78 The Whip . 79 A Marriage ........ 79 Ballad of the Despairing Husband .... 80 If You 81 Just Friends 82 The Three Ladies 83 The Door 83 The Awakening ...... -

Laura Riding Pointed to the Fact That, Looking at the Canon Of

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SANTA CATARINA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS/INGLÊS E LITERATURA CORRESPONDENTE MINDSCAPES: LAURA RIDING’S POETRY AND POETICS por RODRIGO GARCIA LOPES Tese submetida à Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina em cumprimento parcial dos requisitos para obtenção do grau de DOUTOR EM LETRAS FLORI.\NOPOLIS Dezembro de 2000 Esta Tese de Rodrigo Garcia Lopes, intitulada MINDSCAPES: LAURA RIDING’S POETRY AND POETICS, foi julgada adequada e aprovada em sua forma final, pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras/Inglês e Literatura Correspondente, da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, para fms de obtenção do grau de DOUTOR EM LETRAS Área de concentração; Inglês e Literatura Correspondente Opção: Literaturas de Língua Inglesa Anelise Reich Corseuil Coordenadora BANCA EXAMINADORA; é Roberto O ’Shea ientador e Presidente 'h/y Maria Lúcia MiUéo Martins Examinadora Susana Bornéo Funck Examinadora J^iz Angé^o da Costa Examinador ífid Renaux Examinadora Florianópolis, 11 de dezembro de 2000 In the memory of Laura (Riding Jackson (1901-1991) To my parents, Antonio Ubirajara Lopes and Maria do Carmo Garcia Lopes IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the several people and institutions that helped me, in inestimable ways, to succeed in accomplishing the present thesis. To my advisor, José Roberto O’Shea, for his infinite patience, collaboration, and understanding. To CAPES, for conceding me the scholarship that provided the necessary means to carry out original research on Laura Riding collections in the United States. To The Board of Literary Management of tiie late Laura (Riding Jackson: Dr. James Tyler, Dr. William Harmon, Robert Nye, Theodore Wilentz, Joan Wilentz, and especially to Alan J. -

An Erotics of Language in Contemporary American Fiction Flore Chevailier

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 The Body of Writing: An Erotics of Language in Contemporary American Fiction Flore Chevailier Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE BODY OF WRITING: AN EROTICS OF LANGUAGE IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN FICTION By FLORE CHEVAILLIER A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2008 Copyright © 2008 Flore Chevaillier All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Flore Chevaillier defended on May 28th 2008. ______________________________ R.M. Berry Professor Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Antoine Cazé Professor Co-Directing Dissertation ______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member ______________________________ Mathieu Duplay Committee Member ______________________________ Andrew Epstein Committee Member ______________________________ S.E. Gontarski Committee Member ______________________________ François Happe Committee Member ______________________________ Claire Maniez Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________________ R.M. Berry Chair, Department of English The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank R.M. Berry for his guidance, insights, and encouragement during this project and throughout my graduate career. I will miss our conversations. I would also like to acknowledge Antoine Cazé, who introduced me to American experimental fiction. I am grateful for his time, direction, and support during the development of this dissertation and over the course of my undergraduate and graduate studies at the Université d’Orléans.