An Oral History of a Former Mining Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Pressures and Impacts Arising Frm Strategic Development

Report for Scottish Environment Protection Agency/ Neil Deasley Planning and European Affairs Manager Scottish Natural Heritage Scottish Environment Protection Agency Erskine Court The Castle Business Park Identification of Pressures and Impacts Stirling FK9 4TR Arising From Strategic Development Proposed in National Planning Policy Main Contributors and Development Plans Andrew Smith John Pomfret Geoff Bodley Neil Thurston Final Report Anna Cohen Paul Salmon March 2004 Kate Grimsditch Entec UK Limited Issued by ……………………………………………… Andrew Smith Approved by ……………………………………………… John Pomfret Entec UK Limited 6/7 Newton Terrace Glasgow G3 7PJ Scotland Tel: +44 (0) 141 222 1200 Fax: +44 (0) 141 222 1210 Certificate No. FS 13881 Certificate No. EMS 69090 09330 h:\common\environmental current projects\09330 - sepa strategic planning study\c000\final report.doc In accordance with an environmentally responsible approach, this document is printed on recycled paper produced from 100% post-consumer waste or TCF (totally chlorine free) paper COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary Report No: Contractor : Entec UK Ltd BACKGROUND The work was commissioned jointly by SEPA and SNH. The project sought to identify potential pressures and impacts on Scottish Water bodies as a consequence of land use proposals within the current suite of Scottish development Plans and other published strategy documents. The report forms part of the background information being collected by SEPA for the River Basin Characterisation Report in relation to the Water Framework Directive. The project will assist SNH’s environmental audit work by providing an overview of trends in strategic development across Scotland. MAIN FINDINGS Development plans post 1998 were reviewed to ensure up-to-date and relevant information. -

Ridgeway Park 27 Duthil Street, Glasgow G51 4GX

Ridgeway Park 27 Duthil Street, Glasgow G51 4GX Semi Detached Villa Ridgeway Park Fixed Price £149,995 Beautifully presented and in “turnkey” condition, this impressive EXTENDED SEMI VILLA has been imaginatively altered and improved to an uncompromising standard and specification. Generously proportioned throughout, the property comprises a first class family home occupying an enviable position within the ever popular Ridgeway Park. It is only minutes from a wide and varied range of amenities including the recently opened Southern General Hospital Campus, both Braehead and Silverburn shopping centre, Morrison’s at Cardonald, Asda at Govan, access to the Clyde Tunnel, Expressway and motorway, perfect location! Entrance hall, immediately impressive lounge with deep built-in cloaks/storage cupboard and stairs to upper level, fully refitted family sized dining kitchen with integrated oven, hob and hood and patio doors providing access onto enclosed south facing rear garden, double bedroom with deep dressing room off (this could be converted to an en-suite facility, subject to obtaining the relevant planning consents), the ground floor accommodation is completed by a large cloakroom/w.c comprising two piece suite with access from the entrance hall. On the first floor are two large double bedrooms (rear bedroom having built-in fitted mirror wardrobes extending one wall), fully tiled family bathroom comprising three piece white suite with electric instant shower above bath, mosaic tiles full height around walls, large tiles to floor. There is also a floored and lined attic area with access via a fold down ladder and providing good storage space. The property is set amidst private gardens including a large enclosed south facing garden to rear. -

The Association of James Braid Courses 2012

THE ASSOCIATION OF JAMES BRAID COURSES 2012 COURSE ADDRESS OF CONTACT GREEN FEE COUNTRY NAME COURSE DETAILS RATE OFFERED 10 Old Jackson Avenue 001 (914) 478 3475 $60/fri $95/ w/e$135 U.S.A The St. Andrews Hastings‐on‐Hudson [email protected] plus $25.50 for a Golf New York, 10706 www.saintandrewsgolfclub.com Buggy (closed Mon.) Forecaddie required Aberdovey 01654 767 493 £32.50 WALES Aberdovey Gwynedd [email protected] [£20.00 Nov‐Mar] LL35 0RT www.aberdoveygolf.co.uk Newton Park 01874 622004 WALES Brecon Llanfaes [email protected] £10.00 Powys, LD3 8PA www.brecongolfclub.co.uk Old Highwalls 02920 513 682 Highwalls Road [email protected] £15.00 WALES Dinas Powis Dinas Powis www.dpgc.co.uk [w/e £20.00] South Glamorgan CF64 4AJ Trearddur Bay 01407762022 WALES Holyhead Anglesey [email protected] £20.00 LL65 2YL www.holyheadgolfclub.co.uk [w/e &B/H £25.00] Langland Bay Road 01792 361721 Winter £17.00 WALES Langland Bay Mumbles [email protected] [w/e £20.00] Swansea www.langlandbaygolfclub.com Summer £30.00 SA3 4QR [w/e £40.00] Golf Links Road 01597822247 Winter £12.00 WALES Llandrindod Wells Llandrindod Wells [email protected] Summer £15.00 Powys www.lwgc.co.uk [Day £15 & £20] LD1 5NY Hospital Road 01492 876450 £20.00[Mon‐Fri, £25 WALES Maesdu Llandudno [email protected] w/ends, Apr – Oct] North Wales www.maesdugolfclub.co.uk £15.00[any day Nov‐ LL30 1HU Mar] Neath Road 01656 812002 /812003 /734106 WALES Maesteg Maesteg manager@maesteg‐golf.co.uk £15.00 Bridgend or [email protected] [£10.00 Nov‐Mar] S. -

CT & NDR Monitoring 1314

Glasgow City Council Executive Committee Report by Councillor Paul Rooney, City Treasurer Contact: Lynn Brown Ext: 73837 BUDGET MONITORING 2013-14 ; PERIOD 12 Purpose of Report: This report provides a summary of the financial performance for the period 1 April 2013 to 14 February 2014. Recommendations: The Executive Committee is asked to: i. approve the adjustments relating to the revenue budget at section 4 and investment programme at section 5.3 ii. note that this report and all detailed service department reports will be considered by the Finance and Audit Scrutiny Committee Ward No(s): Citywide: Local member(s) advised: Yes No consulted: Yes No PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING: Any Ordnance Survey mapping included within this Report is provided by Glasgow City Council under licence from the Ordnance Survey in order to fulfil its public function to make available Council-held public domain information. Persons viewing this mapping should contact Ordnance Survey Copyright for advice where they wish to licence Ordnance Survey mapping/map data for their own use. The OS web site can be found at <http://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk> " If accessing this Report via the Internet, please note that any mapping is for illustrative purposes only and is not true to any marked scale 1. Introduction 1.1 This report provides a summary of the financial performance for the period 1 April 2013 to 14 February 2014. 2. Reporting Format 2.1 This report provides a summary of the Council’s financial position. This report, together with detailed monitoring reports on a Service basis, will be referred to the Finance and Audit Scrutiny Committee for detailed scrutiny. -

National Retailers.Xlsx

THE NATIONAL / SUNDAY NATIONAL RETAILERS Store Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Post Code M&S ABERDEEN E51 2-28 ST. NICHOLAS STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1BU WHS ST NICHOLAS E48 UNIT E5, ST. NICHOLAS CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW SAINSBURYS E55 UNIT 1 ST NICHOLAS CEN SHOPPING CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW RSMCCOLL130UNIONE53 130 UNION STREET ABERDEEN, GRAMPIAN AB10 1JJ COOP 204UNION E54 204 UNION STREET X ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY CONV E54 SOFA WORKSHOP 206 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY ALF PL E54 492-494 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1TJ TESCO DYCE EXP E44 35 VICTORIA STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1UU TESCO HOLBURN ST E54 207 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BL THISTLE NEWS E54 32 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BT J&C LYNCH E54 66 BROOMHILL ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6HT COOP GT WEST RD E46 485 GREAT WESTERN ROAD X ABERDEEN AB10 6NN TESCO GT WEST RD E46 571 GREAT WESTERN ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6PA CJ LANG ST SWITIN E53 43 ST. SWITHIN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6XL GARTHDEE STORE 19-25 RAMSAY CRESCENT GARTHDEE ABERDEEN AB10 7BL SAINSBURY PFS E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA ASDA BRIDGE OF DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA SAINSBURY G/DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA COSTCUTTER 37 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BN RS MCCOLL 17UNION E53 17 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BU ASDA ABERDEEN BEACH E55 UNIT 11 BEACH BOULEVARD RETAIL PARK LINKS ROAD, ABERDEEN AB11 5EJ M & S UNION SQUARE E51 UNION SQUARE 2&3 SOUTH TERRACE ABERDEEN AB11 5PF SUNNYS E55 36-40 MARKET STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5PL TESCO UNION ST E54 499-501 -

North West Sector Profile

Appendix North West Sector Profile Contents 1. Introduction Page 1 2. Executive Summary Page 2 3. Demographic & Socio – Economic Page 8 4. Labour Market/Employment/Education Page 13 5. Health Page 23 6. Neighbourhood Management Page 29 1. Introduction 1.1 The profile provides comparative information on the North West Sector Community Planning Partnership (CPP) area, including demographic & socio economic, employment, health and neighbourhood management information. 1.2 North West Glasgow is diverse in socio economic terms, as illustrated by the map, as it contains Glasgow’s city centre/ business area, the more affluent west end of Glasgow but also localities with significant issues relating to employment, health and poverty. The North West is the academic centre of the City with the three Glasgow Universities located in the sector and also has many cultural & historical buildings of interest as well as large areas of green space. Table 1: North West Sector Summary Population (2011 Census) 206,483 (up 7.1%) Population (2011 Census) exc. communal establishments 197,419 Working Age Population 16-64 (2011 Census) 151,345 (73.3%) Electorate (2014) 165,009 Occupied Households (2011 Census) 101,884 (up 9.5%) Average Household Size (2011) exc. communal establishments 1.94 (2.07 in 2011) Housing Stock (2014) 105,638 No. of Dwellings per Hectare (2012) 22.28 Out Of Work Benefit Claimants (May 2014) 24,230 (16.0%) Job Seekers Allowance (February 2015) 5,141 (3.4%) 2. Executive Summary Demographic Information 2.1 Population According to the 2011 Census, The North West sector population was 206,483. The population in the North West Sector increased by 13,773 (7.1%) from 2001 Census. -

Glasgow Community Planning Partnership Greater

GLASGOW COMMUNITY PLANNING PARTNERSHIP GREATER POLLOK AREA PARTNERSHIP REGISTER OF BOARD MEMBERS INTERESTS 2020/21 Name Organisation / Project / Trust / Company etc Nature of Interest Councillor Saqib Ahmed The Property Store Property Consultant Glasgow City Council Al-Amin Scotland Trustee Councillor David McDonald Glasgow City Council Depute Leader Glasgow City Council Glasgow Life Director Scottish Cities Alliance Member COSLA Convention Substitute COSLA Leaders (substitute) Member UK Core Cities Member Eurocities Member Glasgow Credit Union Personal member Councillor Rhiannon Spear Time for Inclusive Education Chair Glasgow City Council Councillor Rashid Hussain BAE Systems Employee Glasgow City Council Tony Meechan Scottish Fire & Rescue Service Employee Scottish Fire and Rescue Craig Carenduff Scottish Fire & Rescue Service Employee Scottish Fire and Rescue Alastair MacLellan Househillwood Tenants & Residents Assoc Member Levern and District Priesthill/Househillwood Forum Member Community Council South Sector Community Planning Partnership Member Sadie Hayes Levern and District Community Council Ann Duffy Glasgow City Community Health Partnership- South Sector Employee Glasgow Community Health Partnership Daniel Maher Glasgow City Community Health Partnership- South Sector Employee Glasgow Community Health Partnership Inspector Ryan McMurdo Police Scotland Employee Police Scotland Sergeant Jason McLean Police Scotland Employee Police Scotland Jean Honan South West Community Transport Chair Third Sector Forum SWAMP Board Member Aqeel Ahmed None Scottish Youth Parliament James Peebles Scottish Youth Parliament Sarah Ali Crookston Community Group (BME Community) Nasreen Ali Crookston Community Group (BME Community) Helen McDonald Glasgow Life Employee Hurlet and Brockburn Hurlet and Brockburn Community Council Committee Member Community Council Kathleen Mulloy Hurlet and Brockburn Community Council Catlin Toland St Paul’s High School Pupil St Paul’s High (Youth Rep) Erin Rice St Paul’s High School Pupil St Paul’s High (Youth Rep) . -

Consultation Questions

Alan Greenlees Consultation Questions The answer boxes will expand as you type. Procuring rail passenger services 1. What are the merits of offering the ScotRail franchise as a dual focus franchise and what services should be covered by the economic rail element, and what by the social rail element? Q1 comments: 2. What should be the length of the contract for future franchises, and what factors lead you to this view? Q2 comments: 3. What risk support mechanism should be reflected within the franchise? Q3 comments: 4. What, if any, profit share mechanism should apply within the franchise? Q4 comments: 5. Under what terms should third parties be involved in the operation of passenger rail services? Q5 comments: 6. What is the best way to structure and incentivise the achievement of outcome measures whilst ensuring value for money? Q6 comments: 7. What level of performance bond and/or parent company guarantees are appropriate? Q7 comments: 8. What sanctions should be used to ensure the franchisee fulfils its franchise commitments? Q8 comments: Achieving reliability, performance and service quality 9. Under the franchise, should we incentivise good performance or only penalise poor performance? Q9 comments: 10. Should the performance regime be aligned with actual routes or service groups, or should there be one system for the whole of Scotland? Q10 comments: 11. How can we make the performance regime more aligned with passenger issues? Q11 comments: 12. What should the balance be between journey times and performance? Q12 comments: 13. Is a Service Quality Incentive Regime required? And if so should it cover all aspects of stations and service delivery, or just those being managed through the franchise? Q13 comments: 14. -

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts

Glasgow City Health and Social Care Partnership Health Contacts January 2017 Contents Glasgow City Community Health and Care Centre page 1 North East Locality 2 North West Locality 3 South Locality 4 Adult Protection 5 Child Protection 5 Emergency and Out-of-Hours care 5 Addictions 6 Asylum Seekers 9 Breast Screening 9 Breastfeeding 9 Carers 10 Children and Families 12 Continence Services 15 Dental and Oral Health 16 Dementia 18 Diabetes 19 Dietetics 20 Domestic Abuse 21 Employability 22 Equality 23 Health Improvement 23 Health Centres 25 Hospitals 29 Housing and Homelessness 33 Learning Disabilities 36 Maternity - Family Nurse Partnership 38 Mental Health 39 Psychotherapy 47 NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Psychological Trauma Service 47 Money Advice 49 Nursing 50 Older People 52 Occupational Therapy 52 Physiotherapy 53 Podiatry 54 Rehabilitation Services 54 Respiratory Team 55 Sexual Health 56 Rape and Sexual Assault 56 Stop Smoking 57 Volunteering 57 Young People 58 Public Partnership Forum 60 Comments and Complaints 61 Glasgow City Community Health & Care Partnership Glasgow Health and Social Care Partnership (GCHSCP), Commonwealth House, 32 Albion St, Glasgow G1 1LH. Tel: 0141 287 0499 The Management Team Chief Officer David Williams Chief Officer Finances and Resources Sharon Wearing Chief Officer Planning & Strategy & Chief Social Work Officer Susanne Miller Chief Officer Operations Alex MacKenzie Clincial Director Dr Richard Groden Nurse Director Mari Brannigan Lead Associate Medical Director (Mental Health Services) Dr Michael Smith -

3 Barberry Place, Southpark Village G53 7YS

3 Barberry Place, Southpark Village G53 7YS www.nicolestateagents.co.uk Nicol Estate Agents Description A well presented, three bedroom semi-detached villa set within a quiet cul de sac setting in this popular residential development. A family home with spacious, contemporary and light accommodation arranged over two floors, well designed for family living. The accommodation comprises: Ground Floor: Welcoming hallway with staircase to upper floor. Generous sitting room, open plan to the dining room. Kitchen, which has been recently refitted offering a range of wall mounted and floor standing units and complementary worktop surfaces. Conservatory which looks onto the rear gardens. Situation First Floor: Bedroom one with fitted wardrobes. Bedroom two with fitted wardrobes. Bedroom three. Contemporary house family bathroom, with three piece white suite and shower over bath. This popular suburb is located approximately 8 miles to the South of Glasgow’s City Centre and is conveniently situated The property is further complimented by gas central heating and double glazing. Well kept and tended gardens to front and rear. A driveway provides ample off street parking. for commuter access to nearby M77/M8 & Glasgow Southern Orbital. Darnley, Barrhead, Thornliebank, Giffnock and Newton Mearns are acknowledged for their standard of local amenities and provide a selection of local shops, supermarkets, restaurants, regular bus and rail services to Glasgow City Centre, banks, library and health care facilities. Barberry Place is conveniently located for access to The Avenue shopping centre, Waitrose at Greenlaw Village Retail Park and Sainsbury’s in Darnley. Sports and recreational facilities can be found locally to include Parklands Country Club, David Lloyd Rouken Glen, Cathcart, Williamwood and Whitecraigs golf clubs, Eastwood Theatre and Rouken-Glen Park. -

Campus Travel Guide Final 08092016 PRINT READY

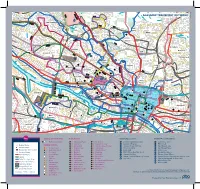

Lochfauld V Farm ersion 1.1 27 Forth and 44 Switchback Road Maryhill F C Road 6 Clyde Canal Road Balmore 1 0 GLASGOW TRANSPORT NETWORK 5 , 6 F 61 Acre0 A d Old Blairdardie oa R Drumchapel Summerston ch lo 20 til 23 High Knightswood B irkin e K F 6 a /6A r s de F 15 n R F 8 o Netherton a High d 39 43 Dawsholm 31 Possil Forth and Clyde Canal Milton Cadder Temple Gilshochill a 38 Maryhill 4 / 4 n F e d a s d /4 r a 4 a o F e River Lambhill R B d Kelvin F a Anniesland o 18 F 9 0 R 6 n /6A 1 40 r 6 u F M 30 a b g Springburn ry n h 20 i ill r R Ruchill p Kelvindale S Scotstounhill o a Balornock 41 d Possil G Jordanhill re Park C at 19 15 W es 14 te rn R 17 37 oa Old Balornock 2 d Forth and D um Kelvinside 16 Clyde b North art 11 Canal on Kelvin t Ro Firhill ad 36 ee 5 tr 1 42 Scotstoun Hamiltonhill S Cowlairs Hyndland 0 F F n e 9 Broomhill 6 F ac 0 r Maryhill Road V , a ic 6 S Pa tor Dowanhill d r ia a k D 0 F o S riv A 8 21 Petershill o e R uth 8 F 6 n F /6 G r A a u C 15 rs b R g c o u n Whiteinch a i b r 7 d e Partickhill F 4 p /4 S F a River Kelvin F 9 7 Hillhead 9 0 7 River 18 Craighall Road Port Sighthill Clyde Partick Woodside Forth and F 15 Dundas Clyde 7 Germiston 7 Woodlands Renfrew Road 10 Dob Canal F bie' 1 14 s Loa 16 n 5 River Kelvin 17 1 5 F H il 7 Pointhouse Road li 18 5 R n 1 o g 25A a t o Shieldhall F 77 Garnethill d M 15 n 1 14 M 21, 23 10 M 17 9 6 F 90 15 13 Alexandra Parade 12 0 26 Townhead 9 8 Linthouse 6 3 F Govan 33 16 29 Blyt3hswood New Town F 34, 34a Anderston © The University of Glasgo North Stobcross Street Cardonald -

Gray, Neil (2015) Neoliberal Urbanism and Spatial Composition in Recessionary Glasgow

Gray, Neil (2015) Neoliberal urbanism and spatial composition in recessionary Glasgow. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/6833/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Neoliberal Urbanism and Spatial Composition in Recessionary Glasgow Neil Gray MRes Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Geographical and Earth Sciences College of Science and Engineering University of Glasgow November 2015 i Abstract This thesis argues that urbanisation has become increasingly central to capital accumulation strategies, and that a politics of space - commensurate with a material conjuncture increasingly subsumed by rentier capitalism - is thus necessarily required. The central research question concerns whether urbanisation represents a general tendency that might provide an immanent dialectical basis for a new spatial politics. I deploy the concept of class composition to address this question. In Italian Autonomist Marxism (AM), class composition is understood as the conceptual and material relation between ‘technical’ and ‘political’ composition: ‘technical composition’ refers to organised capitalist production, capital’s plans as it were; ‘political composition’ refers to the degree to which collective political organisation forms a basis for counter-power.