A Double-Blind, Randomized, Multicenter, Italian Study of Frovatriptan Versus Rizatriptan for the Acute Treatment of Migraine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Are the Acute Treatments for Migraine and How Are They Used?

2. Acute Treatment CQ II-2-1 What are the acute treatments for migraine and how are they used? Recommendation The mainstay of acute treatment for migraine is pharmacotherapy. The drugs used include (1) acetaminophen, (2) non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), (3) ergotamines, (4) triptans and (5) antiemetics. Stratified treatment according to the severity of migraine is recommended: use NSAIDs such as aspirin and naproxen for mild to moderate headache, and use triptans for moderate to severe headache, or even mild to moderate headache when NSAIDs were ineffective in the past. It is necessary to give guidance and cautions to patients having acute attacks, and explain the methods of using medications (timing, dose, frequency of use) and medication use during pregnancy and breast-feeding. Grade A Background and Objective The objective of acute treatment is to resolve the migraine attack completely and rapidly and restore the patient’s normal functions. An ideal treatment should have the following characteristics: (1) resolves pain and associated symptoms rapidly; (2) is consistently effective; (3) no recurrence; (4) no need for additional use of medication; (5) no adverse effects; (6) can be administered by the patients themselves; and (7) low cost. Literature was searched to identify acute treatments that satisfy the above conditions. Comments and Evidence The acute treatment drugs for migraine generally include (1) acetaminophens, (2) non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), (3) ergotamines, (4) triptans, and (5) antiemetics. For severe migraines including status migrainosus and migraine attacks refractory to treatment, (6) anesthetics, and (7) corticosteroids (dexamethasone) are used (Tables 1 and 2).1)-9) There are two approaches to the selection and sequencing of these medications: “step care” and “stratified care”. -

ERJ-01090-2018.Supplement

Shaheen et al Online data supplement Prescribed analgesics in pregnancy and risk of childhood asthma Seif O Shaheen, Cecilia Lundholm, Bronwyn K Brew, Catarina Almqvist. 1 Shaheen et al Figure E1: Data available for analysis Footnote: Numbers refer to adjusted analyses (complete data on covariates) 2 Shaheen et al Table E1. Three classes of analgesics included in the analyses ATC codes Generic drug name Opioids N02AA59 Codeine, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02AA79 Codeine, combinations with psycholeptics N02AA08 Dihydrocodeine N02AA58 Dihydrocodeine, combinations N02AC04 Dextropropoxyphene N02AC54 Dextropropoxyphene, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02AX02 Tramadol Anti-migraine N02CA01 Dihydroergotamine N02CA02 Ergotamine N02CA04 Methysergide N02CA07 Lisuride N02CA51 Dihydroergotamine, combinations N02CA52 Ergotamine, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02CA72 Ergotamine, combinations with psycholeptics N02CC01 Sumatriptan N02CC02 Naratriptan N02CC03 Zolmitriptan N02CC04 Rizatriptan N02CC05 Almotriptan N02CC06 Eletriptan N02CC07 Frovatriptan N02CX01 Pizotifen N02CX02 Clonidine N02CX03 Iprazochrome N02CX05 Dimetotiazine N02CX06 Oxetorone N02CB01 Flumedroxone Paracetamol N02BE01 Paracetamol N02BE51 Paracetamol, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02BE71 Paracetamol, combinations with psycholeptics 3 Shaheen et al Table E2. Frequency of analgesic classes prescribed to the mother during pregnancy Opioids Anti- Paracetamol N % migraine No No No 459,690 93.2 No No Yes 9,091 1.8 Yes No No 15,405 3.1 No Yes No 2,343 0.5 Yes No -

Antimigraine Agents, Triptans Review 07/21/2008

Antimigraine Agents, Triptans Review 07/21/2008 Copyright © 2004 - 2008 by Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage and retrieval system without the express written consent of Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Attention: Copyright Administrator Intellectual Property Department Provider Synergies, L.L.C. 5181 Natorp Blvd., Suite 205 Mason, Ohio 45040 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended -

Frovatriptan Versus Zolmitriptan for the Acute Treatment of Migraine: a Double-Blind, Randomized, Multicenter, Italian Study

Neurol Sci (2010) 31 (Suppl 1):S51–S54 DOI 10.1007/s10072-010-0273-x SYMPOSIUM: NEWS IN TREATMENT OF MIGRAINE ATTACK Frovatriptan versus zolmitriptan for the acute treatment of migraine: a double-blind, randomized, multicenter, Italian study Vincenzo Tullo • Gianni Allais • Michel D. Ferrari • Marcella Curone • Eliana Mea • Stefano Omboni • Chiara Benedetto • Dario Zava • Gennaro Bussone Ó The Author(s) 2010. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The objective of this study is to assess patients’ of PF episodes at 2 h was 26% with F and 31% with Z satisfaction with migraine treatment with frovatriptan (F) (p = NS). PR episodes at 2 h were 57% for F and 58% for or zolmitriptan (Z), by preference questionnaire. 133 sub- Z(p = NS). Rate of recurrence was 21 (F) and 24% jects with a history of migraine with or without aura (IHS (Z; p = NS). Time to recurrence within 48 h was better for criteria) were randomized to F 2.5 mg or Z 2.5 mg. The F especially between 4 and 16 h (p \ 0.05). SPF episodes study had a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, cross- were 18 (F) versus 22% (Z; p = NS). Drug-related adverse over design, with each of the two treatment periods lasting events were significantly (p \ 0.05) less under F (3 vs. 10). no more than 3 months. At the end of the study, patients In conclusion, our study suggests that F has a similar were asked to assign preference to one of the treatments efficacy of Z, with some advantage as regards tolerability (primary endpoint). -

Acute Migraine Treatment

Acute Migraine Treatment Morris Levin, MD Professor of Neurology Director, Headache Center UCSF Department of Neurology San Francisco, CA Mo Levin Disclosures Consulting Royalties Allergan Oxford University Press Supernus Anadem Press Amgen Castle Connolly Med. Publishing Lilly Wiley Blackwell Mo Levin Disclosures Off label uses of medication DHE Antiemetics Zolmitriptan Learning Objectives At the end of the program attendees will be able to 1. List all important options in the acute treatment of migraine 2. Discuss the evidence and guidelines supporting the major migraine acute treatment options 3. Describe potential adverse effects and medication- medication interactions in acute migraine pharmacological treatment Case 27 y/o woman has suffered ever since she can remember from “sick headaches” . Pain is frontal, increases over time and is generally accompanied by nausea and vomiting. She feels depressed. The headache lasts the rest of the day but after sleeping through the night she awakens asymptomatic 1. Diagnosis 2. Severe Headache relief Diagnosis: What do we need to beware of? • Misdiagnosis of primary headache • Secondary causes of headache Red Flags in HA New (recent onset or change in pattern) Effort or Positional Later onset than usual (middle age or later) Meningismus, Febrile AIDS, Cancer or other known Systemic illness - Neurological or psych symptoms or signs Basic principles of Acute Therapy of Headaches • Diagnose properly, including comorbid conditions • Stratify therapy rather than treat in steps • Treat early -

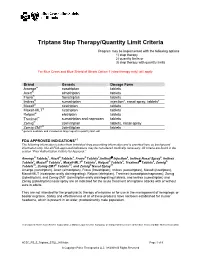

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria Program may be implemented with the following options 1) step therapy 2) quantity limits or 3) step therapy with quantity limits For Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois Option 1 (step therapy only) will apply. Brand Generic Dosage Form Amerge® naratriptan tablets Axert® almotriptan tablets Frova® frovatriptan tablets Imitrex® sumatriptan injection*, nasal spray, tablets* Maxalt® rizatriptan tablets Maxalt-MLT® rizatriptan tablets Relpax® eletriptan tablets Treximet™ sumatriptan and naproxen tablets Zomig® zolmitriptan tablets, nasal spray Zomig-ZMT® zolmitriptan tablets * generic available and included as target agent in quantity limit edit FDA APPROVED INDICATIONS1-7 The following information is taken from individual drug prescribing information and is provided here as background information only. Not all FDA-approved indications may be considered medically necessary. All criteria are found in the section “Prior Authorization Criteria for Approval.” Amerge® Tablets1, Axert® Tablets2, Frova® Tablets3,Imitrex® injection4, Imitrex Nasal Spray5, Imitrex Tablets6, Maxalt® Tablets7, Maxalt-MLT® Tablets7, Relpax® Tablets8, Treximet™ Tablets9, Zomig® Tablets10, Zomig-ZMT® Tablets10, and Zomig® Nasal Spray11 Amerge (naratriptan), Axert (almotriptan), Frova (frovatriptan), Imitrex (sumatriptan), Maxalt (rizatriptan), Maxalt-MLT (rizatriptan orally disintegrating), Relpax (eletriptan), Treximet (sumatriptan/naproxen), Zomig (zolmitriptan), and Zomig-ZMT (zolmitriptan orally disintegrating) tablets, and Imitrex (sumatriptan) and Zomig (zolmitriptan) nasal spray are all indicated for the acute treatment of migraine attacks with or without aura in adults. They are not intended for the prophylactic therapy of migraine or for use in the management of hemiplegic or basilar migraine. Safety and effectiveness of all of these products have not been established for cluster headache, which is present in an older, predominantly male population. -

CP.CPA.217 Triptans.Pdf

Clinical Policy: Triptans Reference Number: CP.CPA.217 Effective Date: 11.16.16 Last Review Date: 11.20 Line of Business: Commercial Revision Log See Important Reminder at the end of this policy for important regulatory and legal information. Description The following are triptans requiring prior authorization and/or quantity limits: naratriptan (Amerge®), almotriptan (Axert®), frovatriptan (Frova®), sumatriptan (Imitrex®, Tosymra™), rizatriptan (Maxalt®/Maxalt-MLT®), eletriptan (Relpax®), sumatriptan/naproxen (Treximet®), zolmitriptan (Zomig®/Zomig® ZMT), Imitrex® injection, Onzetra™ Xsail™, Sumavel™ Dosepro™, and Zembrace™ SymTouch™. FDA Approved Indication(s) Triptans are indicated for the acute treatment of migraine attacks with or without aura in: • Adults (all products) • Pediatric patients (certain products only): o Axert: age 12 to 17 years with a history of migraine attacks usually lasting 4 hours or more (when untreated) o Maxalt, Maxalt MLT: age 6 to 17 years old o Treximet, Zomig Nasal Spray: age 12 to 17 years Imitrex injection and Sumavel DosePro are additionally indicated for the treatment of acute treatment of cluster headache in adults. Limitation(s) of use: • Use only if a clear diagnosis of migraine has been established. If a patient has no response to the first migraine attack treated with a specific triptan, reconsider the diagnosis of migraine before that triptan is administered to treat any subsequent attacks. • Triptans are not indicated for the prevention of migraine attacks. • All triptans except Imitrex injection and Sumavel DosePro: safety and effectiveness of triptans have not been established for cluster headache. • Imitrex injection and Sumavel DosePro: not indicated for the preventative treatment of cluster headache attacks. -

RELPAX® (Eletriptan Hydrobromide) Tablets

RELPAX® (eletriptan hydrobromide) Tablets DESCRIPTION RELPAX® (eletriptan) Tablets contain eletriptan hydrobromide, which is a selective 5 hydroxytryptamine 1B/1D (5-HT1B/1D) receptor agonist. Eletriptan is chemically designated as (R)-3-[(1-Methyl-2-pyrrolidinyl)methyl]-5-[2-(phenylsulfonyl)ethyl]-1H indole monohydrobromide, and it has the following chemical structure: CH OO OO 3 N S . HBr N H The empirical formula is C22H26N2O2S . HBr, representing a molecular weight of 463.40. Eletriptan hydrobromide is a white to light pale colored powder that is readily soluble in water. Each RELPAX Tablet for oral administration contains 24.2 or 48.5 mg of eletriptan hydrobromide equivalent to 20 mg or 40 mg of eletriptan, respectively. Each tablet also contains the inactive ingredients microcrystalline cellulose NF, lactose NF, croscarmellose sodium NF, magnesium stearate NF, titanium dioxide USP, hypromellose, triacetin USP and FD&C Yellow No. 6 aluminum lake. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Mechanism of Action: Eletriptan binds with high affinity to 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D and 5-HT1F receptors, has modest affinity for 5-HT1A, 5-HT1E, 5-HT2B and 5-HT7 receptors, and little or no affinity for 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT5A and 5-HT6 receptors. Eletriptan has no significant affinity or pharmacological activity at adrenergic alpha1, alpha2, or beta; dopaminergic D1 or D2; muscarinic; or opioid receptors. Two theories have been proposed to explain the efficacy of 5-HT receptor agonists in migraine. One theory suggests that activation of 5-HT1 receptors located on intracranial blood vessels, including those on the arteriovenous anastomoses, leads to vasoconstriction, which is correlated with the relief of migraine headache. -

Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management

Guideline: Preoperative Medication Management Guideline for Preoperative Medication Management Purpose of Guideline: To provide guidance to physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), pharmacists, and nurses regarding medication management in the preoperative setting. Background: Appropriate perioperative medication management is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes and prevent medication misadventures.1 Results from a prospective analysis of 1,025 patients admitted to a general surgical unit concluded that patients on at least one medication for a chronic disease are 2.7 times more likely to experience surgical complications compared with those not taking any medications. As the aging population requires more medication use and the availability of various nonprescription medications continues to increase, so does the risk of polypharmacy and the need for perioperative medication guidance.2 There are no well-designed trials to support evidence-based recommendations for perioperative medication management; however, general principles and best practice approaches are available. General considerations for perioperative medication management include a thorough medication history, understanding of the medication pharmacokinetics and potential for withdrawal symptoms, understanding the risks associated with the surgical procedure and the risks of medication discontinuation based on the intended indication. Clinical judgement must be exercised, especially if medication pharmacokinetics are not predictable or there are significant risks associated with inappropriate medication withdrawal (eg, tolerance) or continuation (eg, postsurgical infection).2 Clinical Assessment: Prior to instructing the patient on preoperative medication management, completion of a thorough medication history is recommended – including all information on prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, “as needed” medications, vitamins, supplements, and herbal medications. Allergies should also be verified and documented. -

Frova® Utilization Management Criteria

FROVA® UTILIZATION MANAGEMENT CRITERIA DRUG CLASS: 5HT1 agonists BRAND (generic) NAME: Frova (frovatriptan) tablet 2.5 mg tablet (GCN = 014977) FDA INDICATIONS: Oral frovatriptan is indicated for the acute treatment of migraine with or without aura in adults. The 5-HT1 agonists are not intended for the prophylactic therapy of migraine or for use in the management of hemiplegic or basilar migraine. Safety and effectiveness have also not been established for cluster headache. ICD-9 CODES: Migraine – with aura (“classic”): 346.0 Migraine – idiopathic/without aura (“common”): 346.1 QUANTITY LIMITATIONS (QL) CRITERIA: SHORT TERM: EXTENDED SUPPLY: 30 mg per 30 days 90 mg per 90 days Frova 2.5 mg 12 tablets 36 tablets If patient requires amount in excess of these numbers, please follow Quantity Limitations (QL) criteria for Imitrex. RATIONALE: Frova (frovatriptan) tablets - Frovatriptan has a maximum dose of 7.5 mg per day. Endo has studied frovatriptan in up to 4 migraines per month, or 30 mg per month. CRITERIA FOR EXCEEDING QL: 1. Convey to physician the amount of the drug that the patient has already received (refer to QL criteria) and ask if the patient needs more than that amount. AND 2. Patient must have diagnosis of moderate to severe migraine headache. (Tension type and chronic daily headaches are NOT appropriate diagnoses.) AND 3. Must have tried and failed at least 2 other abortive migraine therapy. Examples of medications used for abortive therapy include: • Ibuprofen (Motrin®) • Diclofenac (Voltaren®) • Flurbiprofen (Ansaid®) • Ergotamine-containing products (Cafergot, Wigraine, Ergomar, etc.) • Isometheptene mucate/Dichloralphenazone/Acetaminophen (Midrin, etc.) AND 4. -

Frovatriptan Vs Zolmitriptan Patient Preference Trial Report Signature

Synopsis of Clinical Study ReportͲƵĚƌĂdŶƵŵďĞƌ͗ϮϬϬϲͲϬϬϬϴϬϱͲϰϮ This Synopsis of Clinical Study Report is provided for patients and healthcare professionals to demonstrate the transparency efforts of the Menarini Group. This document is not intended to replace the advice of a healthcare professional and can not be considered as a recommendation. Patients must always seek medical advice before making any decisions on their treatment. Healthcare Professionals should always refer to the specific labelling information approved for the patient's country or region. Data in this document can not be considered as prescribing advice. The study listed may include approved and non-approved formulations or treatment regimens. Data may differ from published or presented data and are a reflection of the limited information provided here. The results from a single trial need to be considered in the context of the totality of the available clinical research results for a drug. The results from a single study may not reflect the overall results for a drug. The data are property of the Menarini Group or of its licensor(s). Reproduction of all or part of this report is strictly prohibited without prior written permission from an authorized representative of Menarini. Commercial use of the information is strictly prohibited unless with prior written permission of the Menarini Group and is subject to a license fee. Menarini International Operations Luxembourg Protocol MeIn/06/Fro-pp/001 Frovatriptan 2. Synopsis Name of company: Summary table referring (For National -

Triptan Therapy for Acute Migraine

Triptan Therapy for Acute Migraine Headache John Farr Rothrock, MD University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL Deborah I. Friedman, MD, MPH University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX The “triptans” are 5HT-1B/1D receptor agonists that were developed to treat acute migraine and acute cluster headache. Sumatriptan, the original triptan preparation, has been in general use since 1993, so there has been considerable experience with triptans over time. There are currently seven oral triptans on the market in the United States: sumatriptan (Imitrex™), naratriptan (Amerge™), zolmitriptan (Zomig™), rizatriptan (Maxalt™), almotriptan (Axert™), frovatriptan (Frova™), and eletriptan (Relpax™); brand names may differ by country. There is also a combination preparation of oral sumatriptan/naproxen (Treximet™). Two triptans (sumatriptan, zolmitriptan) are marketed as nasal sprays, and sumatriptan is available for subcutaneous injection, including a needle-free subcutaneous delivery system (Sumavel™). Sumatriptan suppositories are marketed in Europe but not in North America. Zolmitriptan and rizatriptan are sold in an oral disintegrating tablet or “melt” formulation as well as in tablet form; while the “melt” formulations may be more convenient (no liquid is required to propel them into the stomach), they are absorbed similarly to regular tablets and there is no evidence to suggest that they work faster than the tablet formulations. Some patients with migraine-associated nausea prefer the disintegrating tablets while others cannot tolerate their taste. Although all of the triptans initially were investigated for the treatment of migraine headache of moderate to severe intensity and were superior to placebo in those pivotal trials, they appear to be more consistently effective when used to treat migraine earlier in the attack, when the headache is still mild to moderate.